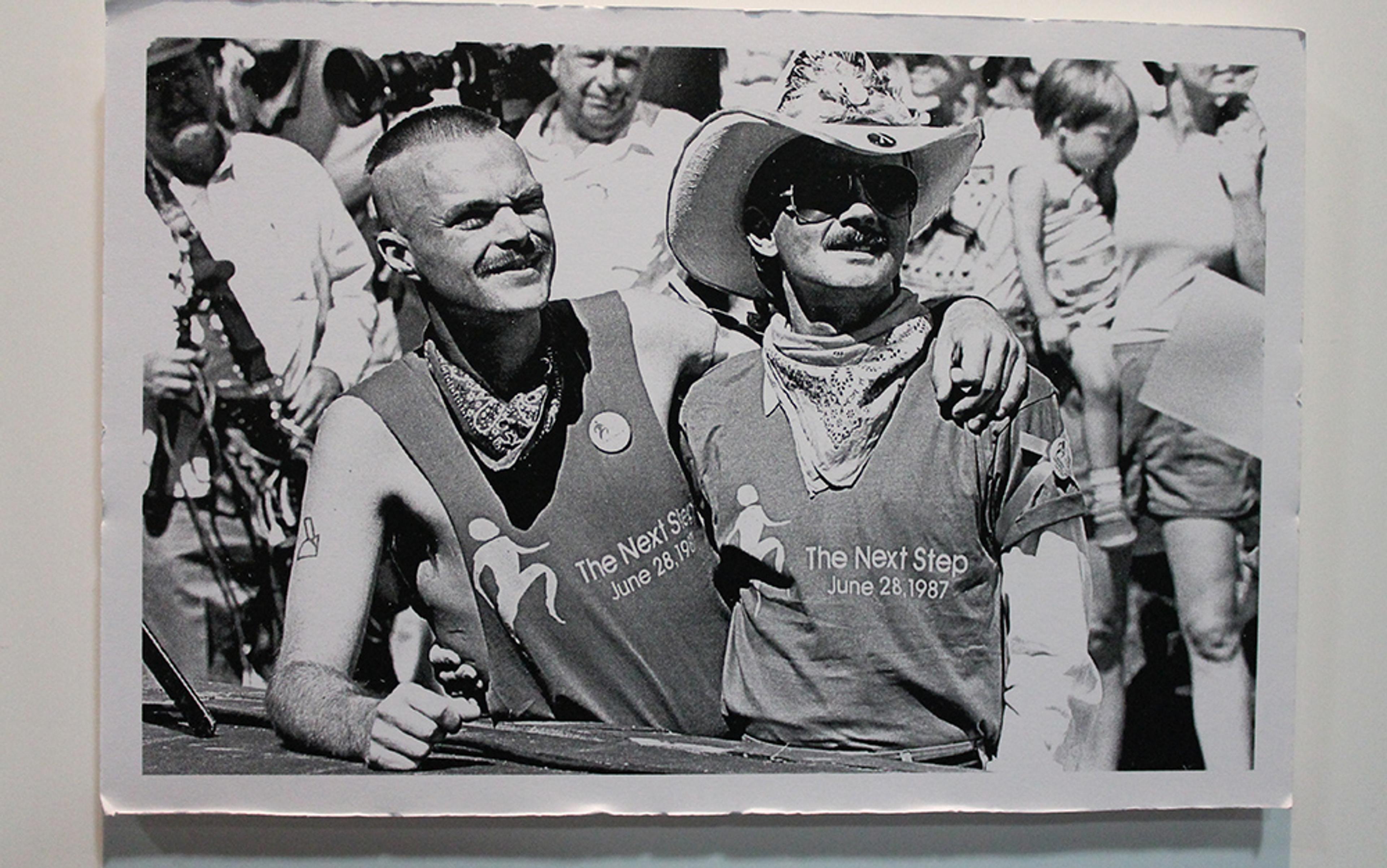

Elvert Barnes Photography/Flickr

How do I teach the history of HIV/AIDS to today’s students? I find myself pondering this question, trying to figure out how to convey the dramatic story of a catastrophic, culturally charged epidemic (one that has claimed nearly 40 million lives) to students for whom HIV has always been a ‘manageable’ illness – at least for those with regular access to antiretroviral therapy.

It’s a challenge of teaching history, of how to convey change, to make sense of how the past became the present. All teachers of modern history face this challenge. A professor of mine recalled the amazement she felt once she taught grad students too young to remember John F Kennedy’s assassination. Or my mother’s bemusement that I teach and write about the 1960s, debunking the tired cliché that ‘you had to be there’. Now I tutor high‑school juniors who were just two years old on 11 September 2001. And when I mention that I spent a semester in the Soviet Union, the look in my students’ eyes tells me I might as well have studied in the Holy Roman Empire.

On the first day of the semester, I toss out one of my icebreaker questions: How did you first hear about AIDS? My students’ answers echo those I’ve heard before. However, the distance, the sense of HIV becoming history, grows louder and louder. They first learned about AIDS through the story of the American basketball player Magic Johnson, perhaps from an older sibling, or a parent; or they watched Rent – the 2005 movie version, not the original 1994 musical. Of course, ‘Africa’ – vague, mysterious, undifferentiated, far away – gets mentioned right away.

I come to my classroom as a member of a sliver of a generation. As a gay man born in 1970, I’m too young to have been swept up in the early plague years, let alone the exuberant sexual culture of the 1970s. But I’m also too old for HIV to have always been a permanent feature of our political, cultural, biomedical and, yes, sexual landscape. Despite asking my students, I don’t precisely remember when I first heard about HIV, but I do recall the arguments about who discovered the HIV virus, the death of Rock Hudson, and the high‑school assembly where we were encouraged to use condoms to protect ourselves from AIDS. I remember my childhood neighbour, five years older than me, who never had much of a chance of escaping infection. Some memories are visceral ones: the odd silences, the bigoted so‑called jokes, the conflation of being gay with dying early, and the fear. Oh, how I remember the sheer terror.

Nowadays, my students were born well into the 1990s, most since the 1996 development of effective anti-retrovirals transformed the epidemic from a near-certain death sentence to a serious but manageable medical condition – at least for those with consistent access to HIV drugs.

The legacy of HIV is all around them, unseen. Condoms have always been easily available all around campus. Studying global public health in college has always been an option, in preparation for a professional career in the field. Their organisations have always walked for AIDS, raced for a cure to cancer, or otherwise raised money for research and direct services inadequately funded by the state.

Following my first semester teaching the course ‘HIV/AIDS: Politics, Culture and Science’ at Harvard, I received a student evaluation complaining that I hadn’t spent enough time talking about Africa. That student is not the first to miss a core theme of a course – in this case, that HIV is far more than Africa, and that Africa is much, much more than HIV. I found myself wishing that the student had complained, correctly and insightfully, that I hadn’t spent enough time covering the epidemic in Boston or Cambridge.

But this comment drove home the urgency of teaching HIV’s history. Then and now, AIDS has always seemed far away – in other bodies, other places, on the other side of the world even. When AIDS and Africa become synonymous, what context do we have to make sense of a 2015 HIV outbreak among impoverished white drug‑users sharing needles in rural Indiana? How can we connect the dots between this crisis and the anti-abortion campaign by conservative state legislators that in 2013 forced Planned Parenthood – the county’s only provider of HIV testing, counselling, and prevention services – to close its doors? For the student versed in the intertwined history of American conservatism and HIV/AIDS, William Faulkner’s admonition that ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past’ is literally all too present.

And yet there is a hunger to learn this history and to talk more about HIV. I’d planned to talk about my research on the 1960s when visiting a Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Studies class at DePauw University in Indiana earlier this year (just weeks before the news broke of the HIV outbreak on the other side of the state). Our discussion instead turned immediately to the essay I’d written for Nursing Clio comparing the controversy surrounding pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with the stigma faced by women using the contraceptive pill upon its introduction in the early 1960s.

That essay prompted one of the most engaged, inquisitive conversations of my teaching career. The students were stunned that they hadn’t heard of a HIV-prevention regimen backed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization with effectiveness approaching 100 per cent. While they lacked detailed knowledge of the epidemic’s history, the analogy between PrEP and the contraceptive pill resonated deeply, as they negotiate community shaming, access to prescription medications, and other obstacles to their own sexual empowerment.

I’ll never know whether any of the students in that classroom later asked a physician to prescribe them PrEP. What I do know is that another couple‑dozen students have new tools to ground their decision-making and to understand how the personal is not only political but historical.

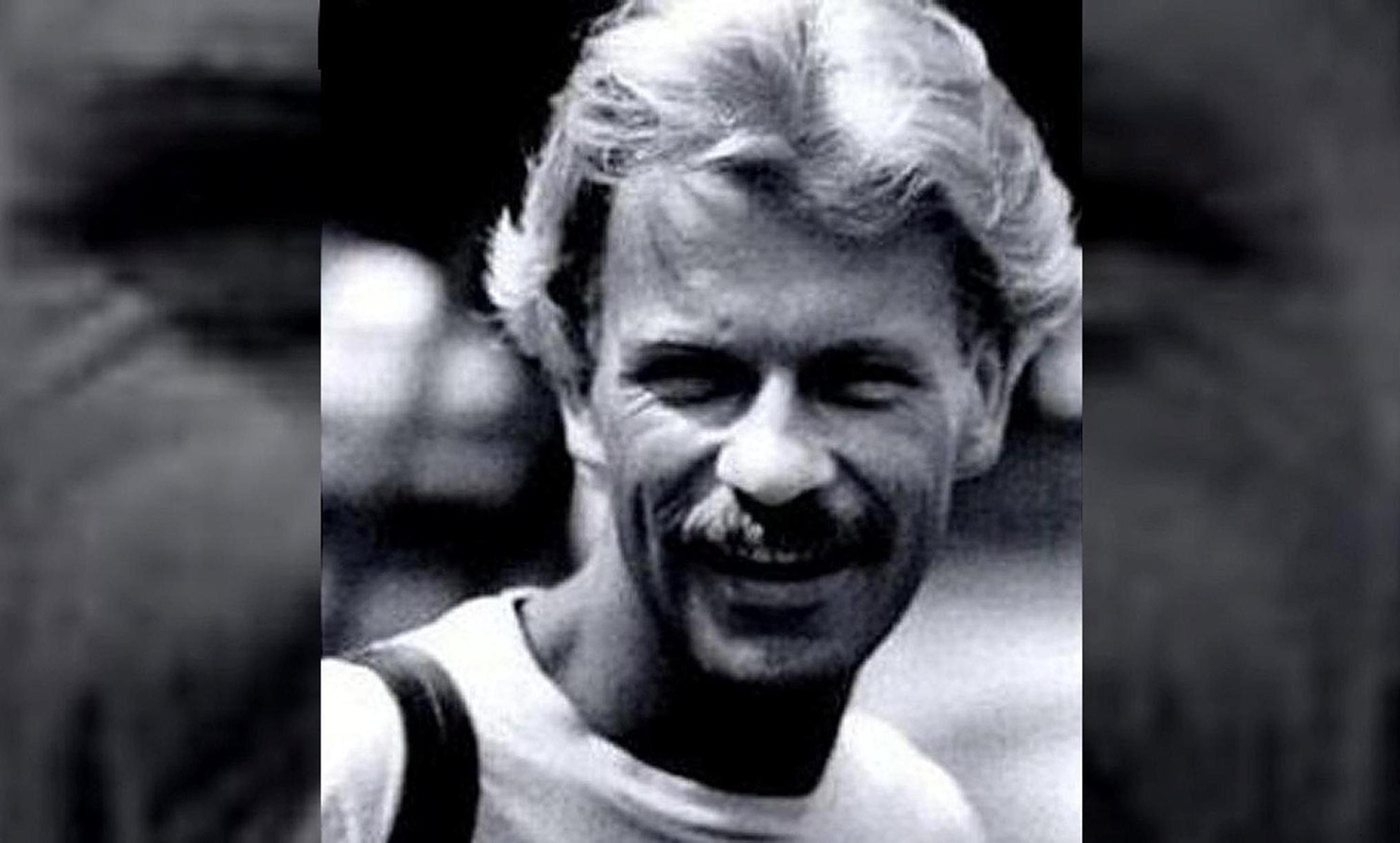

This Opinion is dedicated to Erik Ludwig (1976-2015), my first student to research the cultural politics of HIV/AIDS.