In 2007, Kelvin Leong posted a photograph on his Facebook page. In the picture, he stands in tiny red briefs flexing his biceps. His hands are clenched, his body bent forward to show off his taut, shiny eight-pack. Veins in his arms visibly pulsate. ‘Another variation of side chest pose complete with quad development,’ runs the picture caption: ‘my quads are the result of years of heavy full squats, sometimes to the point of puking.’ Now 33, and training to be a lawyer in the UK, Leong works out every day, saying he wants ‘to be a bit bigger’.

Female body image issues have been flagged up for decades. Women are paraded and berated in the media, told they must be unhappy with their bodies and bombarded with flawless (often Photoshopped) butts, breasts and bellies. But what about men? In past generations men were not expected to be extremely well-muscled. A slight stomach or skinny arms were okay. While many men played sports, few went to the gym merely to beef up. Today, however, shifting gender roles and the rise of social media – where everything is recorded and broadcast on smartphones – has led to increasing pressure on men, as well as on women, to look ‘perfect’.

Many men are ‘obsessed with being lean and muscular’ notes Roberto Olivardia, a clinical psychologist at Harvard Medical School and co-author of The Adonis Complex (2000). The ideal is ‘to look less like Arnold [Schwarzenegger] and more like a Calvin Klein male model’. That means a lean but defined upper body with broad shoulders, tapering to smaller hips in the coveted V-shape, ‘cut’ or ‘ripped’ arms and abs, and next to no body hair.

Images of this hyper-sexualised, commodified male are everywhere, from Hollywood films to glossy magazines and billboard advertising. British journalist Mark Simpson calls them ‘spornosexuals,’ men who want to look like sportsmen or porn stars, chiselling their physiques through a cocktail of gym sessions, diets and drugs. The spornosexual has evolved from the ‘metrosexual’, a term Simpson popularised in the 1990s. While the metrosexual puffs and preens, the spornosexual sculpts. Aesthetics trump sports or performance. And for the first time in history, the buff and the beautiful can spread their bodies to the world instantaneously via Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Seeking acceptance from peers is key. ‘I don’t really care about what the girls think,’ said Leong. His Facebook audience are friends or fellow enthusiasts who offer a minute appraisal of body parts: more toning needed here, trim the excess fat there. Discussions focus on how to maximise results. This is a visual culture for men, by men. ‘It’s something for people to appreciate,’ Leong told me. ‘If we have been dieting for the whole week and we have better abdominals to show, why can’t people admire you?’

There is a flipside to admiration: insecurity and criticism. Sometimes mental illness. Working out retains a sheen of good health, even when it reaches dangerous levels. Because of appearances, problems can be hard to discern: eating disorders go undetected, drug violations unseen. Use of anabolic steroids and aggressive fat-strippers can morph into muscle dysmorphia, a disorder in which putting on muscle mass becomes all-consuming. One study in the United States, published in the journal Depression and Anxiety in 2010, found that 50 per cent of sufferers surveyed had attempted suicide at least once.

Media outlets such as the Daily Mail and TMZ.com now hold men to the same impossible standards as women. Muscular bodies are praised, and the rich and famous mocked for their ‘man boobs’. Celebrities are not the only targets. In a 2012 survey by the Centre for Appearance Research at the University of the West of England in Bristol, 30 per cent of men said they’d heard others referring to their ‘beer belly’ and 19 per cent to their ‘moobs’ (man boobs). Three in five said such ‘body talk’ affected them negatively.

It’s hardly surprising then that men’s body dissatisfaction tripled from 1972 to 1997, according to The Adonis Complex. The pressure to bulk up has hit adolescents particularly hard: a US study published in the journal Pediatrics in 2012 revealed that 90 per cent of high-school and middle-school males exercised to gain muscle; 38 per cent used protein supplements, and nearly 6 per cent illegal steroids.

Muscle-bound men have been revered from antiquity, their sinewy forms deified through the Greek gods, Roman gladiators and Michelangelo’s sculptures. In the 1980s, Arnold Schwarzenegger hauled bodybuilding into the mainstream. Arnie was an Austrian strongman, the Terminator no less, and yet most men did not want to be Schwarzenegger, much less look like him – he was mocked as much as he was worshipped, as a robotic, rock-solid aberration.

‘We’ve idolised this athletic warrior type, but it’s been accepted that most people didn’t aspire to be that,’ explained Timothy Baghurst, a specialist in male body image at Oklahoma State University. ‘Portraits in the 16th century aren’t of tough soldiers – they are more commanders and leaders whose physique isn’t that important.’ In post-subsistence industrialised societies, brains and birthrights have always trumped brawn.

So what has changed? Why the scrabble for muscle today? The beginning of an answer lies with the Charles Atlas comics. In 1921, the Italian-American Angelo Sicilian won the Most Perfectly Developed Man contest in Manhattan, sparking the launch of his landmark exercise programme and comic-inspired advertisements, in which a ‘97-pound weakling’ is usually beaten up by a bully until he gets his Atlas training regime, returning reformed to take revenge. The message was simple: get muscles, win the girl, and live happily ever after. This was what real men who wanted a ‘real body’ did. Slogans blared: ‘Let Me PROVE I Can Make YOU A NEW MAN!’

In a 2005 study of pastoral nomads of northern Kenya, Harrison G Pope, Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard, and the psychologists Shaun Filiault and Benjamin C Campbell at Boston University discovered that perceptions of masculinity hung not on muscle mass but on other forms of overt virility, such as raiding, and protecting livestock. In the US, by contrast, the overt use of physical force is now unacceptable in society. Muscles, and the lionisation of sport – essentially a tribal pursuit – have risen to fill the gap.

Factoring in comic-book heroes completes the triangulation. Superman and Batman, inventions of the 1930s, were shaped in part by American football, which rose to popularity in the same era, argues Charlotte A Jirousek in ‘Superstars, Superheroes and the Male Body Image’ (1996). Football uniforms exaggerated a bulky top body, enhanced by shoulder pads, and a slim waist, while comic-book characters sported ‘super shoulders’, exerting pressure on their male readers to bulk up.

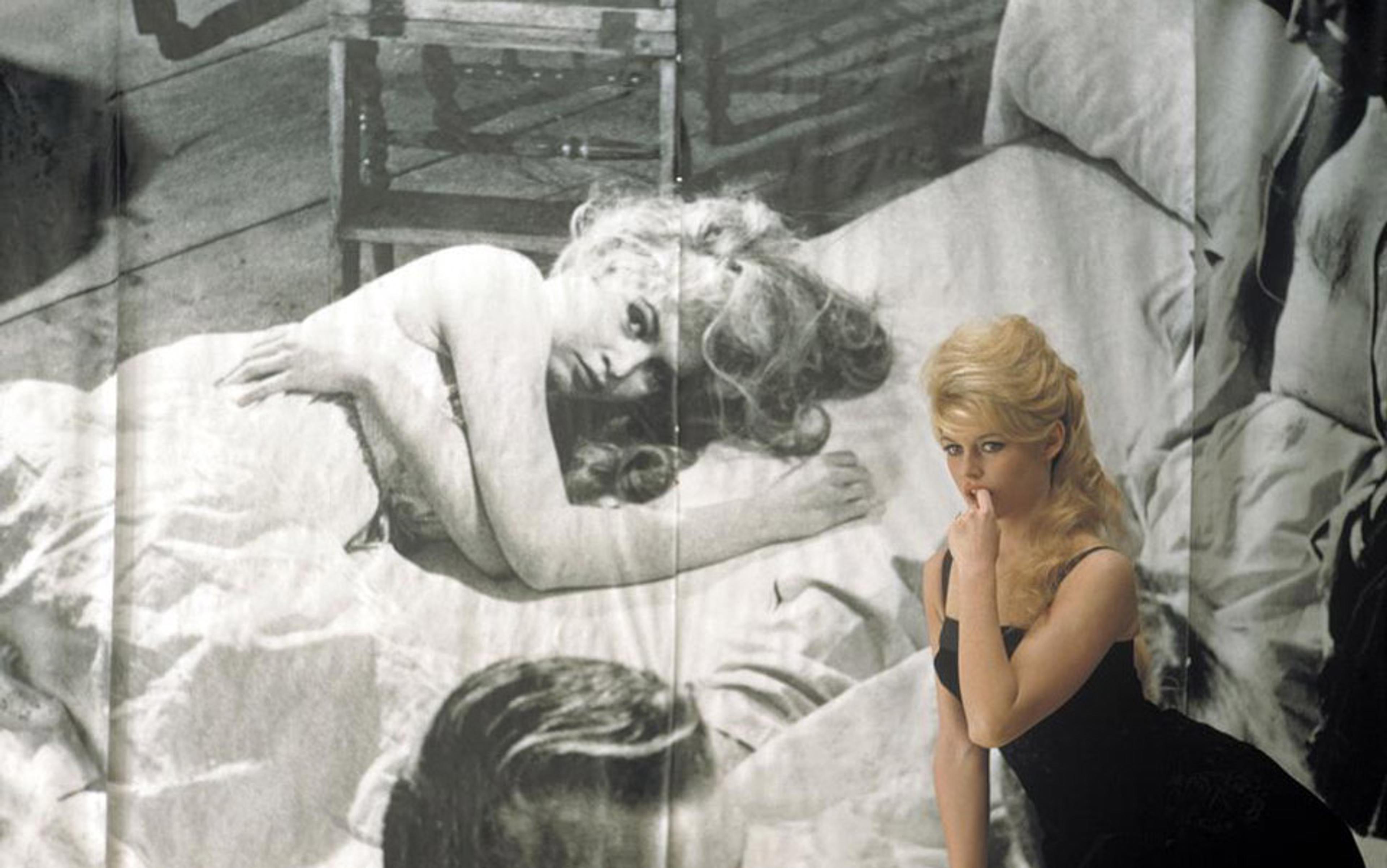

Few iconic characters exhibit this shift towards beefiness better than James Bond, the secret intelligence officer, code name 007. As envisaged by his creator, the British writer Ian Fleming in the 1950s, James Bond was debonair and sophisticated, with an appeal derived from wit and charm, and inhabiting a world in which women were little more than secretaries and sexual temptresses. In the later film adaptations, Sean Connery as Bond looked good in a suit but he was never stacked. Then came Daniel Craig and that scene in Casino Royale (2006) in which he strode out of the sea in a pair of skin-tight trunks, ripped chest streaming with water. Ostensibly, it paid homage to Ursula Andress who did the same in Dr No (1962). But it also announced to the world that male bodies would now be just as fetishised as female ones.

But who is doing the fetishising? Not women. In 2000, The American Journal of Psychiatry published a telling experiment led by Pope at Harvard. College-aged men in Austria, France and the US were asked to choose both their ideal male body and the body they believed women preferred. In all three countries, men picked an ideal on average 28 lb (12.7 kg) more muscular than their own – and they believed that women wanted a male body 30 lb (13.6 kg) more muscular. The men consistently overestimated the appeal of brawn, while women, when asked, preferred an ‘ordinary’ body without the added muscle.

Boys are now taught from childhood that bigger is best, with morality increasingly pinned to body shape. In the film Captain America (2001), based on the comic-book original of 1941, the young protagonist is rejected from the US army for being too scrawny, until he takes part in a top-secret military experiment that transforms him into a super-soldier. The new buff Captain America leads the battle against the Nazi-backed bid for world domination. As Griffiths, the Sydney psychologist, wryly said to me: ‘It’s probably the best analogue for steroids I’ve ever seen.’

While the Barbie doll’s body has been getting thinner and thinner over the years, action figures such as GI Joe have been getting more muscular. It is not only size but definition. One study, co-authored by Harvard’s Pope and Olivardia in 1999, compared action toys from different decades. The earliest models had no abdominal muscles; the 1970s models showed some; but by the mid-1990s the toys displayed ‘the sharply rippled abdominals of an advanced bodybuilder’. Tellingly, Ken, Barbie’s boyfriend, was the exception, but then he is regarded as a doll not an action figure, and is aimed at girls.

‘fat’ signals laziness and a loss of control, but sharp abs are the opposite: you can see the work that’s gone into honing them

In 2008, Baghurst at Oklahoma State University took this a step further. He presented the older, smaller action toys alongside newer, bigger models to pre-adolescent and adolescent boys in a US school. Nine in 10 boys liked the newer ones more – mainly because they were larger, with 72 per cent claiming that the more muscular figures appeared to be healthier. ‘We now have these action figures that are bigger than we can possibly achieve, even with steroids. What is that teaching our children?’ asks Baghurst.

One explanation for the now grossly oversized action toys is the growth of anabolic steroid use from the 1960s onwards. For the first time, men could enlarge themselves to non-human, Hulk-like proportions. A knee-jerk reaction to obesity might be another reason: for much of society, ‘fat’ signals a lack of discipline, loss of control and laziness. Sharp abs, by contrast, patently manifest the opposite traits: you can (literally) see the work that’s gone into honing them.

Feeding into this pressure is the booming male beauty business. Today, there is an unprecedented diversification along gender lines of products such as moisturisers, and a burgeoning dietary supplements industry – much of it unregulated. Quick fixes are on the rise, too. Online apps such as Selfie Gym (‘take your selfie from simple to #ripped in seconds’) can retrospectively add the appearance of muscles on photographs.

In Australia, Dion Nucifora, 28, works out six times a week; meanwhile his father, a construction labourer, maintains his own fitness, strength and masculinity by more gentle means: swimming laps. At the end of the week, while his dad’s generation might choose to let off steam with evening drinks, Nucifora, an insurance worker and part-time model, goes back to the gym or to boot camp with his co workers – knitting together male relations in the same way as alcohol once did.

In a piece on the rise of the spornosexual, Mark Simpson recently told Esquire magazine that men have ‘learned that in a visual world if you aren’t noticed you just don’t exist’. By that measure, Nucifora certainly exists: his topless selfies with abs rippling receive thousands of ‘likes’ on Instagram. In one year alone, Nucifora has collected more than 7,000 followers. Yet such numbers pale beside social media superstars such as the Bulgarian physical trainer Lazar Angelov whose Instagram followers number almost 1.6 million.

‘It’s all about first impressions; people who have the leanest body and are well-groomed are the ones who get the most attention,’ Nucifora told me. Dating apps such as Tinder, in which you choose a mate based on a photograph, swiping ‘right’ to denote interest and ‘left’ to reject them, have only increased visual currencies. As Nucifora put it: ‘If you haven’t taken care of your appearance, you are going to be that person swiped left every time.’

To some degree, shifting fashions are in play. Marilyn Monroe gave way to Twiggy in the 1960s, but now super-skinny is losing some traction to voluptuous backsides, courtesy of Kim Kardashian and Meghan Trainor. Perhaps the quest for muscles will also transmute into something else. What is certain is that in a world of increasing scrutiny – online and off – body image issues can no longer simply be regarded as a female problem.

Leong, for one, isn’t ready to quit yet. There is always scope to get bigger, always time to pursue the dream of the perfect body. He posts: ‘You can’t just reach a plateau and then stop there. Bruce Lee always said that we have to surpass our plateau or die trying. To have no limit as our limit.’