‘I have a great deal of company in my house; especially in the morning, when nobody calls.’ Henry David Thoreau’s remark about his experience of solitude expresses many of the common ideas we have about the work — and the apparent privileges — of being alone. As he put it so vividly in Walden (1854), his classic account of the time he spent alone in the Massachusetts woods, he went there to ‘live deep and suck out all the marrow of life’. Similarly, when I retreat into solitude, I hope to reconnect with a wider, more-than-human world and by so doing become more fully alive, recovering what the Gospel of Thomas called, ‘he who was, before he came into being’.

It has always been a key step on the ‘way’ or ‘path’ in Taoist philosophy (‘way’ being the literal translation of Tao) to go into the wilderness and lay oneself bare to whatever one finds there, whether that be the agonies of St Anthony, or the detachment of the Taoist masters. Alone in the wild, we shed the conventions that keep society ticking over — freedom from the clock, in particular, is a hugely important factor. We are opened up to other, less conventional, customs: in the wild, animals may talk to us, birds will sometimes guide us to water or light, the wind may become a second skin. In the wild, we may even find our true bodies, creaturely and vivid and indivisible from the rest of creation — but this comes only when we break free, not just from the constraints of clock and calendar and social convention, but also from the sometimes-clandestine hopes, expectations and fears with which we arrived.

For many of us, solitude is tempting because it is ‘the place of purification’, as the Israeli philosopher Martin Buber called it. Our aspiration for travelling to that place might be the simple pleasure of being away, unburdened by the pettiness and corruption of the day-to-day round. For me, being alone is about staying sane in a noisy and cluttered world – I have what the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould called a ‘high solitude quotient’ — but it is also a way of opening out a creative space, to give myself a chance to be quiet enough to see or hear what happens next.

There are those who are inclined to be purely temporary dwellers in the wilderness, who don’t stay long. As soon as they are renewed by a spell of lonely contemplation, they are eager to return to the everyday fray. Meanwhile, the committed wilderness dwellers are after something more. Yet, even if contemplative solitude gives them a glimpse of the sublime (or, if they are so disposed, the divine), questions arise immediately afterwards. What now? What is the purpose of this solitude? Whom does it serve?

Solitude can enliven a new sense of what companionship means

To take oneself out into the wilderness as part of a spiritual quest is one thing, but to remain there in a kind of barren ecstasy is another. The Anglo-American mystic Thomas Merton argues that ‘there is no greater disaster in the spiritual life than to be immersed in unreality, for life is maintained and nourished in us by our vital relation with realities outside and above us. When our life feeds on unreality, it must starve.’ If practised as part of a living spiritual path, he says, and not simply as an escape from corruption or as an expression of misanthropy, ‘your solitude will bear immense fruit in the souls of men you will never see on earth’. It is a point Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thoreau’s friend and teacher, also makes. Solitude is essential to the spiritual path, he argues, but ‘we require such solitude as shall hold us to its revelations when we are in the streets and in palaces … it is not the circumstances of seeing more or fewer people but the readiness of sympathy that imports’.

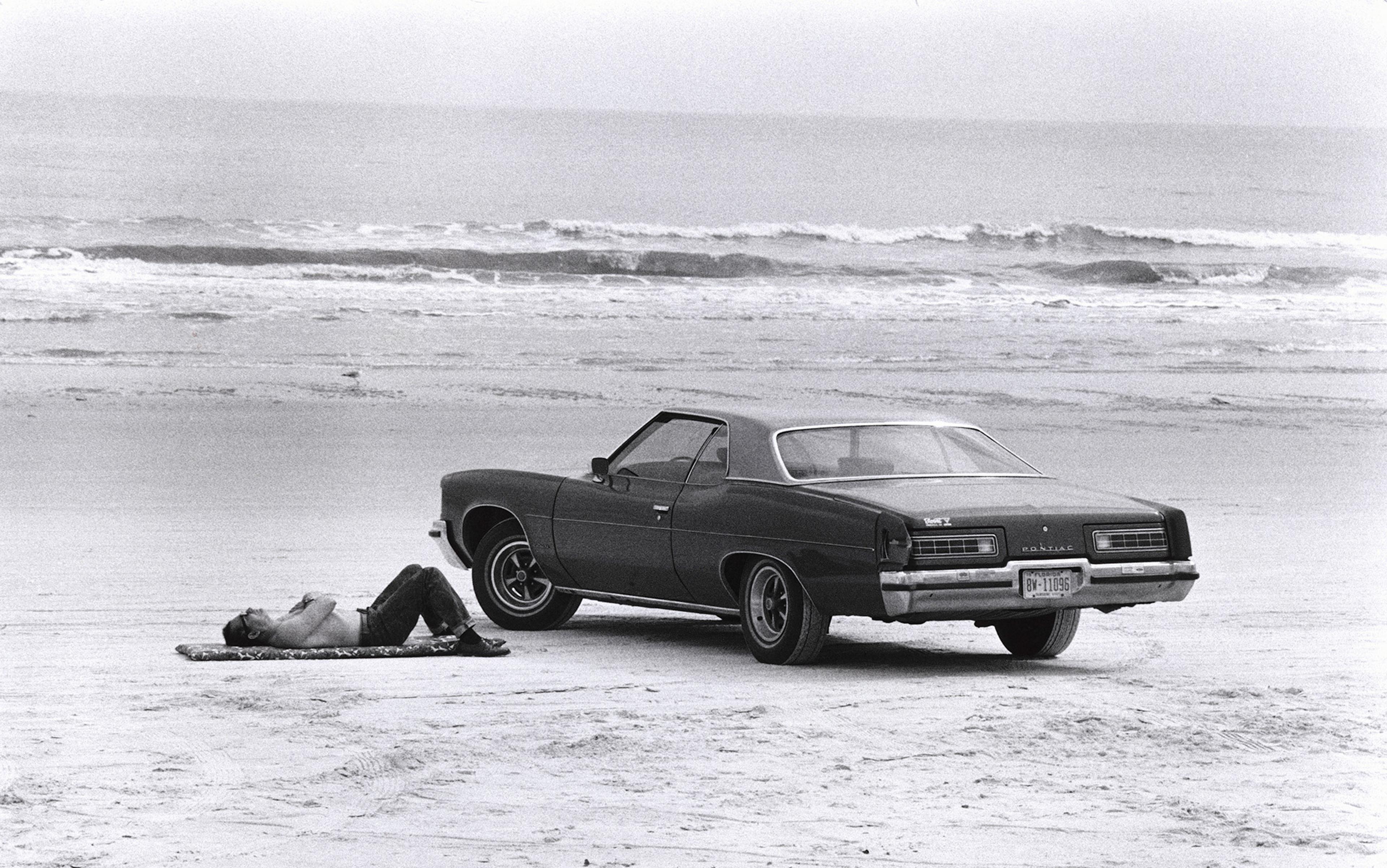

Thoreau, however, felt keenly the corruption of a politically compromised, profit-oriented, slave-keeping society. His posthumously published work Cape Cod (1865) is, at least in part, an expression of dismay, even grief, in which he revealed his desire to turn his back on American society. Yet for much of his life, he kept Emerson’s principle close, as he remembers in Walden:

There too, as everywhere, I sometimes expected the Visitor who never comes. The Vishnu Purana says, ‘The house-holder is to remain at eventide in his courtyard as long as it takes to milk a cow, or longer if he pleases, to await the arrival of a guest.’ I often performed this duty of hospitality, waited long enough to milk a whole herd of cows, but did not see the man approaching from the town.

Perhaps the ‘Visitor who never comes’ is the man approaching from town – or perhaps it is some other, more mysterious – and perhaps less benevolent arrival. As Merton cautioned, the wilderness is a place of becoming lost, as much as found. ‘First, the desert is the country of madness. Second, it is the refuge of the devil, thrown out … to “wander in dry places”. Thirst drives men mad, and the devil himself is mad with a kind of thirst for his own lost excellence — lost because he has immured himself in it and closed out everything else.’

Karl Marx expresses this idea in another way. In his A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1844) he says, ‘what difference is there between the history of our freedom and the history of the boar’s freedom if it can be found only in the forests? … It is common knowledge that the forest echoes back what you shout into it.’ Marx saw religion — and by implication, the spiritual life in general — as ‘the opium of the people,’ but the important point is the need to be careful of the dangers of forest thinking. As in every fairy tale and medieval romance, the wilderness is peopled with dragons, but only some of them are native to the place. The rest are introduced by the solitary pilgrim himself, whose quest had seemed so pure and well-intentioned when he set out.

If solitude does not lead us back to society, it can become a spiritual dead end, an act of self-indulgence or escapism, as Merton, Emerson, Thoreau, and the Taoist masters all knew. We might admire the freedom of the wild boar, we might even envy it, but as long as others are enslaved, or hungry, or held captive by social conventions, it is our duty to return and do what we can for their liberation. For the old cliché is true: no matter what I do, I cannot be free while others are enslaved, I cannot be truly happy while others suffer. And, no matter how sublime or close to the divine my solitary hut in the wilderness might be, it is a sterile paradise of emptiness and rage unless I am prepared to return and participate actively in the social world. Thoreau, that icon of solitary contemplation, did eventually return to support the cause of abolition. In so doing, he laid down the principles of civil disobedience that would later inspire Gandhi, Martin Luther King and the freedom fighters of anti-imperialist movements throughout the world.

‘No man is an island, entire of itself,’ wrote John Donne, in a too-often quoted line, but the full impact comes in the continuation of his meditation, where he writes:

every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

It is one of the great paradoxes of solitude, that it offers us not an escape, not a paradise, not a dwelling place where we can haughtily maintain our integrity by ignoring a vicious and corrupt social world, but a way back to that world, and a new motive for being there. Moreover, it can enliven a new sense of what companionship means — and, with it, a courtesy and hospitability that goes beyond anything good manners might decree. Because, no matter who I am, and no matter what I might or might not have achieved, my very life depends on being prepared, always, for the one visitor who never comes, but might arrive at any moment, from the woods or from the town.