What accounts for the persistent appeal of the self-proclaimed Islamic State (or ISIS) to recruits from Chicago, Bradford or Melbourne? This year, the question became urgent to commentators and policymakers in Europe and the United States. The group’s battlefield successes, its territorial ambitions and viral spectacles of cruelty were made only more ominous by the small but steady stream of recruits it attracted from wealthy democracies.

Some of the proposed explanations have been familiar: the marginalisation and alienation of Muslim minorities in the West; a religious zeal that transcends the smallness of secular life; even the group’s thrillingly extreme apocalyptic vision. It’s not hard to see ISIS as another gruesome camp-follower to modern democratic capitalism, one in a series of terrorist movements and guerrilla insurgencies that feed upon the discontents of the age and the psychoses of their members.

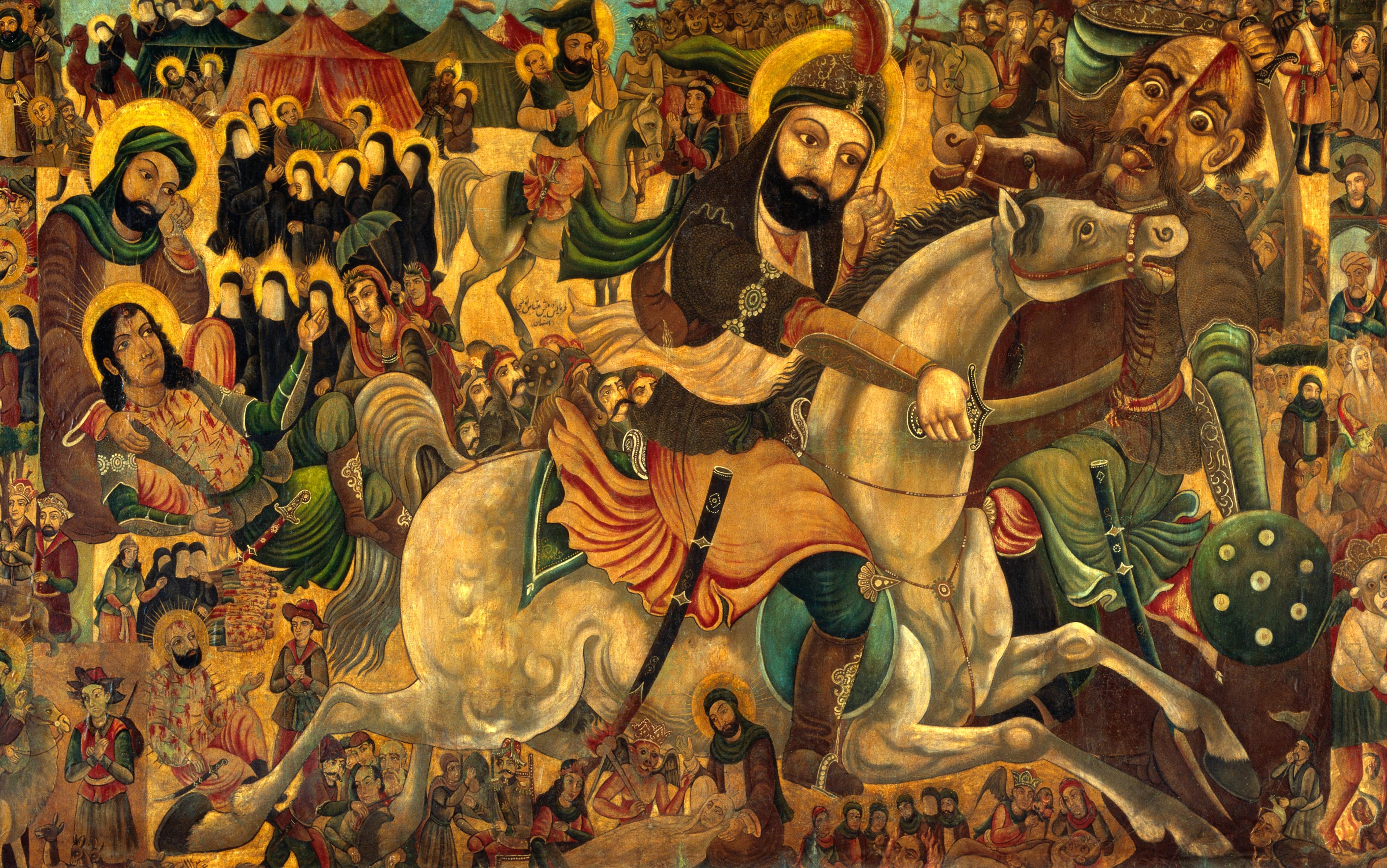

But the story of the arrival and lingering global charisma of ISIS features something that sets it apart: the idea of the Caliphate. Last June, the ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared himself caliph. The grandiosity of the claim was likely lost even on many educated non-Muslim observers. A position that has been gone from Islam in anything but name for 1,000 years, the caliph has to meet certain requirements: he must control territory, must enforce sharia law within it, and he must descend from the Quraysh tribe, the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad (the Ottoman emperors claimed the title into the 20th century, but their claim is widely rejected because they did not descend from the Quraysh). Pledging allegiance to a valid caliph, when one is available, is an obligation that ISIS supporters view as binding on all Muslims. And while Baghdadi’s claim has been divisive even in the world of violent jihadism, groups in Nigeria and Libya have apparently made this vow of allegiance.

In English-language accounts, the idea of the caliphate and its evident appeal seems by turns exotic and ridiculous. ‘[T]his kind of transnational Islam seems to hold special appeal to young Europeans caught between competing identities,’ wrote Malise Ruthven in The New York Review of Books this February. For all the violence of ISIS, the idea of the Caliphate encodes ‘a moral order that transcends not just the boundaries of the national state, but the moral logic underpinning it’. Or, in the words of Nick Danforth writing in Foreign Affairs last year, it is ‘a political fantasy – a blank slate’ for the demands and ambitions of local politics.

Whether its central claim is an inscrutable dream of religiously legitimated sovereignty or a malleable delusion, the appeal of ISIS is easily abstracted from motives available to outsiders. It is, in the incisive words of the New York artist Molly Crabapple, a ‘cosplay Caliphate’, a dress-up festival of blood-soaked nostalgia whose very pretensions to antiquity mark it as the rankest kind of modern innovation.

ISIS and its ideology are violent, reactionary, wholly at odds with the ethos of democracy and progress cherished by modern secular societies. But the myth on which its appeal hinges – and the historical dress-up it seems to engage in – is not as foreign as it seems. A lot of people like cosplay. ‘One of the Islamic State’s less bloody videos shows a group of jihadists burning their French, British and Australian passports,’ Graeme Wood reported in his lengthy study of ISIS ideology in The Atlantic this March. ‘This would be an eccentric act for someone intending to return to blow himself up in line at the Louvre.’ Apparently, these people actually want to live under a caliph.

Far from being a parochially Islamic impulse or a nerd’s fantasy – something you can get involved in from ‘your mama’s basement’, as one counter-terrorism expert has said – the myth of the Caliphate echoes dreams of transcendent legitimacy that are deeply embedded in European culture and literature. To find a story of a sovereign authority long lapsed in kingship but still entitled to the allegiance of all the just, and fated to reappear at an auspicious moment, we need look no further than The Lord of the Rings (1954-55).

J R R Tolkien’s sprawling, leisurely epic – itself a bit of literary cosplay – has managed only to grow in commercial and critical stature since was first published. It has at its heart the revelation of Aragorn as the king of men and his return to his long-vacant ancestral throne. As the story begins, Aragorn is preternaturally competent yet rustic. Over time, he proves himself both a biological heir and a worthy mirror of his kingly ancestors. His transcendent authority occasionally flashes forth, like ‘a king returning from exile to his own land’. Haloes of light gather around his head at particularly kingly moments, such as extracting aid from potential allies at sword-point.

Halo or no, however, the problem of legitimacy and allegiance endures throughout the story. The royal line has been extinguished in the kingdom for 1,000 years, during which a line of non-royal stewards has ruled. But ‘10,000 years would not suffice’ to make the best of a bad situation and simply round up the stewards to the rank of kings. The ancient signs of royalty – most notably a 3,000-year-old sword – are critical for Aragorn to persuade a long-kingless people to accept him. He has a tendency to cry out the name of his most illustrious ancestor when crashing into battle, and attracts dream-like expressions of allegiance. A ‘light of knowledge and love was kindled’ in the eyes of a man restored by Aragorn’s particular – and uniquely kingly – gift for healing. ‘My Lord, you called me. I come. What does the king command?’

many of Tolkien’s readers thrill to the notion of finding a king to whom they can pledge their swords without scruple or hesitation

Such moments, which savour somewhat of kitsch, do not adequately convey the tug of this myth of inherent legitimacy. Tolkien was not difficult to surpass as a writer of action scenes or characterisation. His exceptional accomplishment was very different. He created a history nearly as long and broad as Europe’s. Then he put at its centre an idea of transcendent, divine-right power that – unlike its balderdash real-world inspiration – actually makes the engine move. Tolkien’s history is an automaton with a beating heart.

The parallel between Tolkien’s version of restoration and Baghdadi’s is limited. Aragorn displays magnanimity in victory rather than mass beheadings. Tolkien’s mythology, unlike that of ISIS, is steadfastly un-apocalyptic. But many readers, it seems, thrill to the notion of finding a king to whom they can pledge their swords without scruple or hesitation. Indeed, it is sometimes claimed that the patently adolescent politics of Tolkien’s Middle Earth represent a true and valid model for real-world humans.

Legitimate authority vouchsafed by blood and virtue, by descent from, and imitation of, the heroic past, can slice through the pragmatic reciprocity of government based on social contract. The novel even makes a sidelong allusion to this facet of its own appeal via the character of Arwen, Aragorn’s half-elven, half-human betrothed. Forced to choose between elven immortality and a mortal life with the restored king, she chooses the latter. Her competing identities resolve in this heroic gesture. She sacrifices the higher attainments and comforts of elvish civilisation and burns her passport.

In his tale of a lost line of kings emerging from ancient obscurity, Tolkien adapts a fairytale pattern identified by the 19th-century English scholar E S Hartland as the Sleeping Hero. The sleeping hero, or the king in the mountain, is a great personage who exists, so to say, in suspended animation until a moment of historical crisis. Neither Aragorn nor any of his fathers, it should be noted, attempted to reclaim the throne of Gondor during a national debate on road construction. At a signal – often the sound of a trumpet – the sleeping hero awakes and sets things to rights in the land.

The most famous English example is King Arthur, ‘the once and future king’, shrouded in the mists of Avalon until a time of dire need. Arthur is paralleled by King Wenceslaus of Bohemia, who by some accounts goes out with his riders each night, and whose return will be heralded by the unseasonable blossoming of a certain tree. (Not to be outdone on this score, Tolkien gives Aragorn a sacred tree of his own to restore to Gondor.) Germany has Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor dead since the First Crusade but waiting to be revealed again.

Hartland claimed that every sleeping hero was a lightly historicised version of a pagan god vanquished by Christianity. But Jesus himself combines the figures of the lost scion and the sleeping hero. According to the Gospels, the crowds in Jerusalem greeted the Galilean prophet and healer as ‘the Son of David’, heir to a divinely instituted royal line lost for half a millennium, come back to redeem the people from their bondage to the Roman Empire. At the same time, Christians confess that He ‘will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead’, echoing many such promises recorded in the New Testament. Christian Europe never successfully housed a myth of universal earthly rule analogous to the Caliphate. But Christian Europe did look for the return of Jesus at times of famine, plague and particularly unjust government.

Much of the Christian US does so today. The visions of His return were not necessarily peaceful and conciliatory. The role of Jesus in ISIS eschatology – He will return to kill the armies of ‘Rome’ in the last battle – is not so terribly different from the role assigned to Him in Christian apocalyptic writing.

With the closing of Europe’s folklore frontier in the 19th and 20th centuries, the sleeping heroes were forced to migrate, along with many other fairy-world figures, from communal myth to modern literary culture. Even the wild and dangerous Jesus awaited by the peasant rebels and mad monks of the Middle Ages was largely domesticated by political theology.

But something strange happened: this world of mass-market publishing, parliamentary coalitions and industrial towns loved the old heroes as much as the oral culture that cultivated them ever had. An Arthurian revival stretched from Romantic verse to animated film to serial comic strip to Broadway. Civic groups formed to imitate the virtues of Arthurian legends. And Arthur’s shade was hardly the only one summoned by countrymen in crisis. Hitler named his invasion of the Soviet Union after Frederic Barbarossa.

As European political and religious institutions teetered, frayed or fell altogether, a desire for irrefutable alternatives was perhaps to be expected. Stories that could collapse past and present across the fallow years in between, stories in which the lost heroism and inherent legitimacy of the past overwhelm the compromises and half-measures of the present, had a new urgency. From Aslan to Captain America, sleeping heroes and lost scions arose to fulfil that desire. Ancient and undefiled kingship – even the consciously anachronistic echo of such kingship – could perhaps claim the loyalties of people riven by class struggle and pauperised by failed leaders. Modern echoes, in the Muslim world and beyond, are not hard to hear.

the allure of a ruler who promises to transcend the dreary give-and-take of democratic politics should be familiar

The desire to see the sleeping hero wake and return in a blaze of undeniable authority is not simply a childish reverie. It is no mere reactionary filigree in 20th-century literary fantasies. The ghost of transcendent personal legitimacy still stalks the modern world. It lingers in the background of every democratic attempt at a political dynasty. It can even attach to impersonal forces. A movement of scholars and advocates in the US characterises the Constitution itself as being ‘in exile’, awaiting restoration through devoted judicial activism.

This ghost can haunt the highest of high culture. In his longest poem, ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’ (written in 1875-6), Gerard Manley Hopkins imagines a renewal of Catholic England. It’s a vision that reflects his own process of conversion, his plea to God to ‘Wring thy rebel, dogged in den/Man’s malice, with wrecking and storm.’ He prays that Christ would return to England – ‘Kind, but royally reclaiming his own’:

Remember us in the roads, the heaven-haven of the Reward:

Our King back, oh, upon English souls!

Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us, be a crimson-cresseted east,

More brightening her, rare-dear Britain, as his reign rolls,

Pride, rose, prince, hero of us, high-priest,

Our hearts’ charity’s hearth’s fire, our thoughts’ chivalry’s throng’s Lord.

This prayer is, of course, very different from the sadistic ambitions of ISIS. There is no wave of purifying violence envisioned here. Even judged as verse, the poem is not reactionary; when Hopkins wrote it, it was too innovative in its rhythm and rhetoric for the editor of Britain’s Jesuit magazine. It wouldn’t see publication until 1918, decades after the poet’s death.

But then, as ever, the hypermodern form and the ancient fantasy combine with a persuasive force no mere nostalgia can attain. The king, the hero, the long-absent lord summons, personally and authoritatively, the louche, riotous knights of English minds to chivalry and greatness. The land has suffered the absence of Christ’s true Church for three centuries. It has endured pretenders – stewards, emirs – who have lacked pedigree, rectitude, or both. It has been subject to what Wood, explaining the appeal of ISIS in The Atlantic, calls ‘life’s hypocrisies and inconsistencies’, its slow drift toward shallow belief and low stakes. I’m neither English nor Catholic, but every time I read that stanza I share in its shudder of expectation.

The foreign fighters of ISIS ‘believe that they are personally involved in struggles beyond their own lives’, says Wood, ‘and that merely to be swept up in the drama, on the side of righteousness, is a privilege’. We might view such motivations as a pathology, or as a revulsion against modernity fuelled by poverty and oppression. But we can do this only if we overlook their prominence in stories that root much closer to home.

The horrific violence of ISIS raises questions that literary parallels can’t answer. Not everyone is so fortunate to have orcs (or, in the case of Hopkins, Anglicans) as a world-historical foe. Yet the allure of a ruler who promises to transcend the dreary give-and-take of democratic politics and the deeply compromised, deeply qualified goods it aims to secure, should be familiar. Its danger is not obviously confined to an insurgency in the Middle East.

Perhaps relatively few people, in the Islamic world or outside of it, actually believe they will see the vanquishing of mere politics by transcendent, legitimate authority. But a lot of us enjoy dreaming about it in one form or another, and unlike King Wenceslaus’ riders, such dreams do not always fade at dawn.