In the middle of Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Lord Henry gives Dorian a yellow book. It is a strange book: a novel without a plot, and ‘the heavy odour of incense seemed to cling about its pages and to trouble the brain.’ Captivated, he reads it in ‘a form of reverie, a malady of dreaming, that made him unconscious of the falling day and creeping shadows.’ Like its hero, and with Henry’s encouragement, Dorian enters into a lifelong pursuit of thrilling experiences. He travels the world for Roman Catholic rituals, Eastern perfumes, music from faraway tribal peoples, Renaissance tapestries, and loses himself in imagining the sins of his ancestors, whose corrupted blood runs through his veins.

The Yellow Book, Volume 1, April 1894. Courtesy Wikipedia

Dorian exults in each new sensation until he becomes bored by it, then thrilled once more by the novelty of another sensual experience, till that too is exhausted. His pursuit of intense sensations becomes sordid and nihilistic. In his endeavour to feel everything, at the cost of all those who love him, Dorian is ultimately left with nothing. He is the quintessential Decadent, and, on its publication, The Picture of Dorian Gray was at once hailed and derided as the epitome of the phenomenon termed ‘Decadence’.

At its most extreme, Decadence is a reckless pursuit of intense sensations: one that often teeters on the brink of scandal and sometimes topples over. When Dorian Gray was used as evidence against its author in the decade’s most sensational trial in 1895, there was a moral backlash against the so-called ‘Decadent movement’. In recent decades, the term decadence has been appropriated as a marketing pitch to describe purchasable moments of self-indulgence – a box of chocolate truffles or a spa afternoon at a mid-price chain hotel. However, as it has become a consumer product, decadence has been shorn of its very modern questions about the place of pleasure in our lives and its potential to change our values forever, and these are worth asking.

The Decadent movement began in mid-19th-century Paris. The writers who first defined it and wore the term as a badge, were punks avant la lettre who looked back to the Roman Empire as it collapsed into a torpid, degenerate civilisation as a precedent for their own era. In Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil, 1857), Charles Baudelaire’s poetry captured the perverse pleasure of witnessing decay around them. In the novel À rebours (Against Nature, 1884), Joris-Karl Huysmans’s hero retreats to a mansion alone to experience a series of sensual pleasures. ‘What it wants,’ the French journalist Anatole Baju wrote of Decadence in 1887, ‘is life; it is thirsty for the intensity of life shaped by progress, it needs to get drunk on it … and to set itself aquiver.’

As Decadence migrated to Britain in the 1860s, this endeavour to set things ‘aquiver’ became a response to new and pressing questions that ran deep into the spiritual foundations of Western society. William Thomson published his theory of entropy in 1850. Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859 and The Descent of Man in 1871. In Essays and Reviews (1860), seven prominent members of the Church of England challenged the orthodoxy of the Anglican Church. Alexander Bain founded the psychology journal Mind in 1876. Their works raised innumerable questions for scientific thought and challenges to religious faith.

For Decadence, though, these merged in one existential problem: if, in deep time, the individual is but an ephemeral speck as evolution and entropy imply; if urban migration has unfastened the social and familial ties that define how people should live; if doubt in the verities of Church of England doctrine opens larger, unanswerable metaphysical questions; if we are strangers even to ourselves with unconscious drives we cannot understand as the emerging field of psychology theorised, then how do we make life meaningful? These questions still resonate for many of us today.

Life should be formed around ‘moments’ of ecstasy salvaged from the reality of our ultimate fate

In his infamous Conclusion to Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) – a book that is neither a history nor much about the Renaissance – Walter Pater takes up this question. Preaching from the wreckage of the old certainties, he declares that the ‘awful brevity’ of life and its ever-changing conditions can yield a vibrant new consciousness in which each moment is worthwhile for its own sake. Pater suggests that:

To burn always with this hard gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life … For art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake.

This is Pater all aquiver. His delicious proposal is that life could be reevaluated not around reason, virtue, duty, hard work or kindness, because these values are based on shaky faith in God and society. Instead, life should be valued and formed around ‘moments’ of intense sensation; moments of ecstasy salvaged from the reality of our ultimate fate – and meaninglessness.

The oft-cited message of Pater’s Conclusion had the potential to be both liberating and dangerous. Most immediately, though, it was scandalous. For it replaces René Descartes’s cogito ergo sum with sentio ergo sum, and its highly wrought, jewelled prose style put sensual pleasure, not realism, at its core. The Bishop of Oxford preached a sermon against it, warning that it threatened to lead students ‘miserably astray’. He had a point; it probably did. In the effort to make life meaningful for the individual, overwhelmed by the conditions of modern life, Pater’s position creates further problems. When the pursuit of pleasure becomes the imperative of life, is excessive indulgence the inevitable end? If man is the measure of all things, but with sensation, not reason, at his core, is it possible to moderate behaviour?

Pater didn’t want a scandal, so in 1877 he withdrew his Conclusion from the second edition of The Renaissance, but to no avail: it had already taken on a life of its own. Or, to be more exact, it was taking on multiple artistic lives. Dorian Gray’s story is just one version of what might follow. When Lord Henry incites Dorian to live for pleasure, he pointedly pastiches the Conclusion, but Pater’s intimation of ecstasy is a glimpse of how it would feel to let go; whereas Dorian Gray shows us what it would be to never again get a grip.

Dorian’s version of Decadence filled the popular imagination when Decadence became an ostentatiously stylish zeitgeist – stylish being the operative word. For Decadent style encapsulated the attitude of being hellbent on thrilling experiences. In novels like Dorian Gray, this took shape as a catalogue of fetishised descriptions for the reader’s vicarious excitement. In life – as Decadence spanned out into an amorphous commitment to pleasure for its own sake – among various privileged sets, it was typified by the English novelist Ronald Firbank buying armfuls of exotic flowers, or the Roman plunge pool in Pola Negri’s living room in Hollywood. And why not? Lord Henry would counsel that ultimately nothing matters: the heavens will always echo empty, the ground beneath us will never stabilise, the things that are good will not last, while, in the centre, the fragile mortal is diseased and decayed, doomed to death eternal. Faced with such a fate, we need a new hedonism – allegedly. Should we, though, take it as far as a mouthful of truffles at the spa, or go the full Dorian Gray?

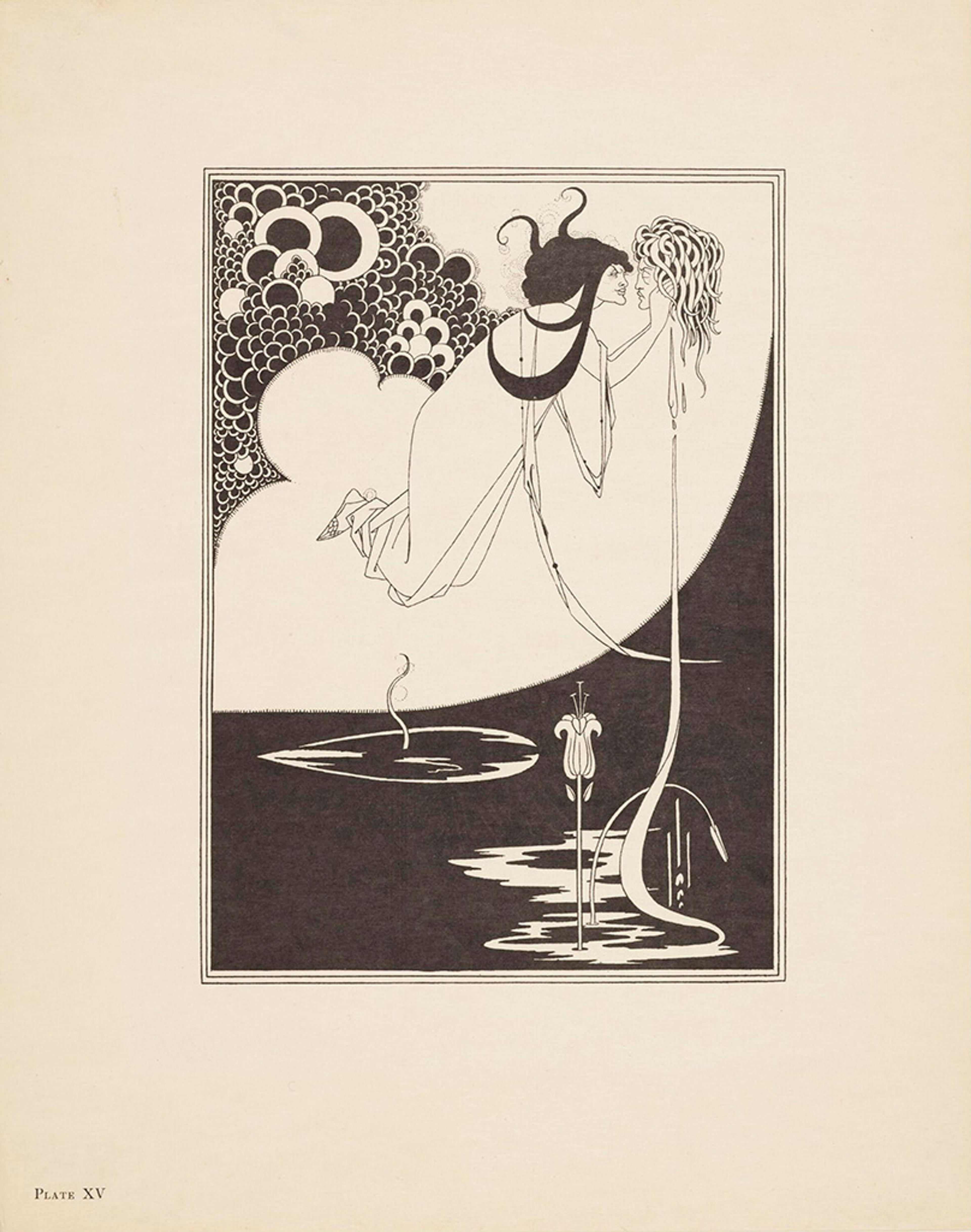

In Decadent art as in Decadent life, style and pleasure were intertwined with a vivid sense of life’s futility. The wunderkind artist Aubrey Beardsley is the ultimate example: he depicted moments of orgiastic revelry in strong blocks of black and white, inspired by Japanese woodcuts. In ‘The Climax’ (1893), Salome is about to kiss the severed head of John the Baptist. Suspended in the air with his head held close to hers, she embodies unabashed sexual desire and anticipation of its fulfilment. It is not only what Beardsley depicts that is obscene here; it is how. The figures are caricatured, drawn ironically in economical, voluptuous lines that disengage art from the real world. Plant stems prick the water beneath in schoolboy innuendoes, while blood runs from the head like a sinuous ribbon into a puddle beneath. In the background, stylised peacock feathers appear on a cloud, as symbols of gratuitous beauty.

The Climax (1893) by Aubrey Beardsley. Courtesy the V&A Museum, London

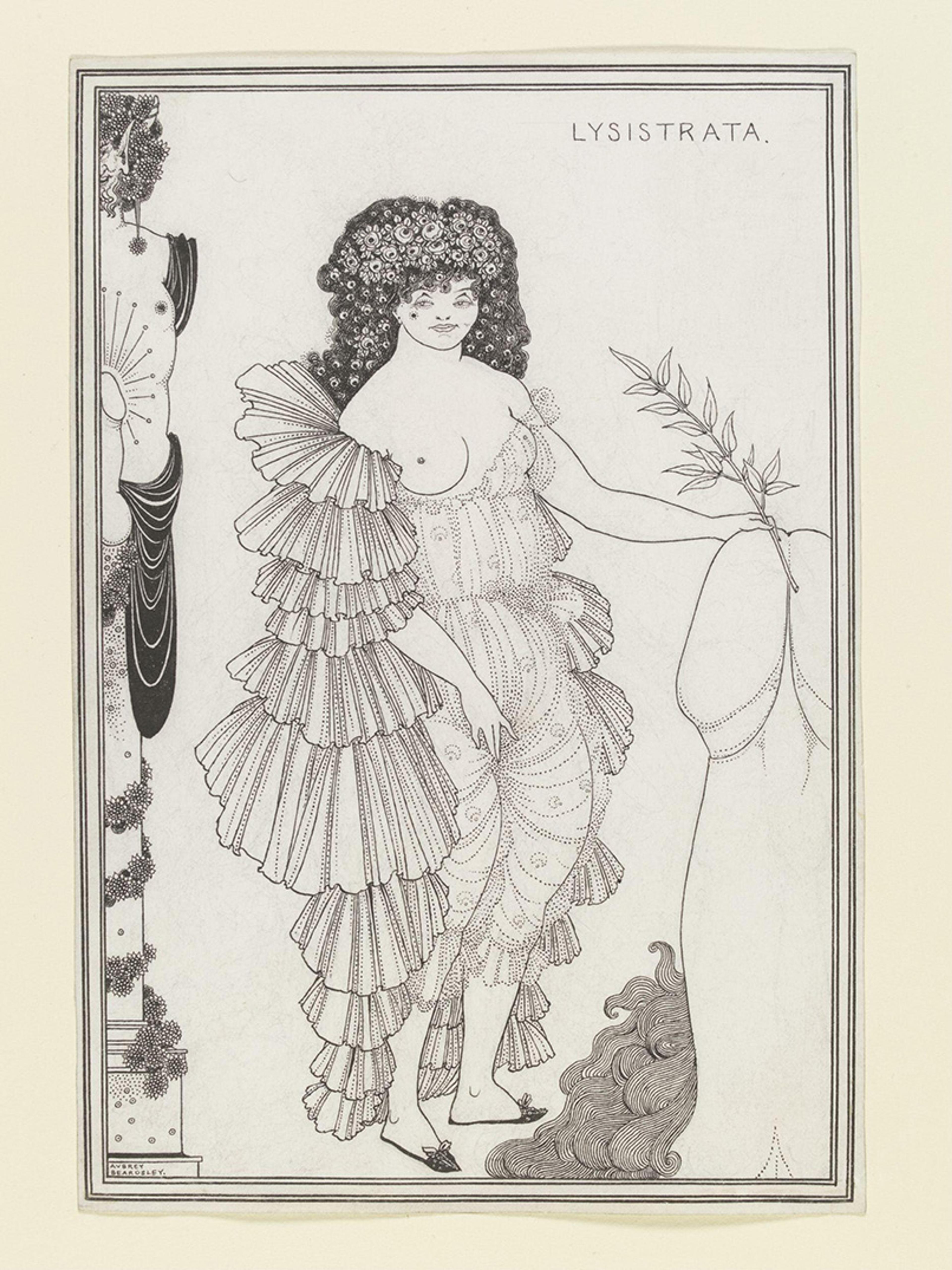

The people in Beardsley’s pictures know what the Victorians didn’t like to admit: we are sensual creatures, and bodies are instruments of desire. Such stylised depictions take sin and make it naughty, tossing aside ethical norms without compunction. Beardsley went further in his 1896 illustrations for Aristophanes’ bawdy comedy Lysistrata, which are overtly pornographic, featuring outlandishly large erect penises and women touching themselves and each other. They are obscene. They are funny. Are they disgusting? Many Victorians thought so. But depicted with Beardsley’s characteristic clean black lines, the naked bodies have a simplicity that shrugs off moral censure, or tries to, while extravagantly detailed drapes and stockings invite the viewer to luxuriate in their eroticism instead.

The pleasure-imperative is a style of writing and a way of life. It doesn’t end well

Decadent styles ranged widely but they all meant to prick the moralistic pretensions of the Victorian era and to do so in such a way that transgression looked like fun. As the art editor of the journal The Yellow Book, Beardsley’s cover designs were embossed onto deep yellow boards. The colour was an ambivalent symbol of excitement and decay: a yellow of disease and of French novels (including the book that changed Dorian Gray’s life), but also of sunflowers and Chartreuse.

Lysistrata Shielding her Coynte (1896) by Aubrey Beardsley. Courtesy the V&A Museum, London

Alongside Beardsley, Wilde made Decadent style and its ethos into a spirit of the age. ‘One should sympathise with the joy, the beauty, the colour of life,’ he writes in the play A Woman of No Importance (1893). ‘The less said about life’s sores the better …’ Like Beardsley’s extravagant, naughty lines, Wilde’s epigrams are seductive. Their style charms us out of the values we thought we held by putting received wisdom into free play. They soon became a trend. The first compendium, titled Oscariana: Epigrams, was published in 1895. Innumerable collections and imitations followed. ‘A conscience is an immediate annoyance, whereas ideals are charming procrastinations,’ the future screenwriter Ben Hecht wrote in his debut novel Erik Dorn (1921). In the film I’m No Angel (1933), Mae West told Cary Grant: ‘When I’m good I’m very good, but when I’m bad I’m better.’ And in his memoir Dandy in the Underworld (2007), the English artist Sebastian Horsley counselled that ‘The trouble with doing nothing, you see, is that you can never take any time off.’

For Horsley, as for Dorian and Wilde, the pleasure-imperative is a style of writing and a way of life. It doesn’t end well. In the fictional case, dizzy with hubris, Dorian dies by his own hand, alone, in disgrace. Most readers miss the novel’s moral, but its protagonist’s ignoble death epitomises the destructive possible ends of Decadence. Self-annihilation may not be the worst of it. In the effort to style out crushing existential anxieties, our humanity is at stake: Dorian isn’t only dead; he is unloved.

Similarly, Lord Illingworth’s doctrine of pleasure may at first charm audiences in A Woman of No Importance, but he turns out to be a cad who carelessly wrecks the lives of people who would love him and who might have brought him a richer joy than the sensual pleasures he lives for. Meanwhile, Horsley was a self-destructive dandy, living for drugs and sex as a coping strategy in the face of almost unbearable childhood trauma. ‘Was I hurt?’ he asks after a being snubbed by a close friend, before a bolshy epigram takes over: ‘I was really upset. There is nothing worse than not being invited to a party that you wouldn’t be seen dead at.’ Wit is the implacable front Horsley uses to cope with his emotions, and to some extent many of us do it. If it becomes a way of life, by which to feel only on the surfaces and at the heights of human experience, it can become sex without love, taste without nourishment, wit that takes the place of sincerity for fear of being found out.

When Decadence arrived in the shops in a carnival of stylish quips, designs and motifs, its risqué and existential dimensions were pragmatically put into the background. Liberty of London printed fabrics with peacock feather designs. Yellow fabric became a popular choice for dresses, in a reaction against the demure soft pastels. Strictly speaking, William Morris’s designs for fabrics and rugs were not Decadent but Wilde counselled, after Morris, that people should ‘have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’. So Morris’s simplified floral patterns were rolled into the Decadent endeavour for ostentatious beauty. The message was simple: for those who didn’t really want to live fast and die young, Decadence could be packaged as a token by which shoppers might briefly taste it ‘simply for those moments’ sake’. The peacock feathers, together with orchids, yellow and Beardsley’s strong simple black lines, symbolised eroticism, irreverence and – in sweeping away the cluttered realism of high-Victorian art – modernity.

George du Maurier’s cartoons for Punch satirised the trend: in An Infelicitous Question, an overdressed young man stands amid exotic flowers, patterned wallpaper and drapes and, with his hands clasped near his heart, tells his guests: ‘I hope by degrees to have this room filled with nothing but the most perfectly beautiful things…’ At which point, he is interrupted when a ‘Simple-Minded Guardsman’, looking at the room, asks: ‘And what are you going to do with these, then?’

An Infelicitous Question by George du Maurier. Public domain

Simple-minded he may be, but the Guardsman says what Du Maurier and other respectable, serious-minded Victorians were thinking. And not only serious-minded but straight-minded. In a velvet jacket with a limp-wristed pose, the overdressed young man is effeminate. For Wilde and other men who didn’t fit into rigid Victorian society, Decadent style offered alternative ways of being a man, based not on the practicality and stiff-upper-lip courage promulgated by Boy’s Own adventures, but on pleasure, creativity and sartorial fashioning as a symbol of sexual difference as ‘gay’ and ‘camp’. It was an affront to the concept of what a gentleman was, and the beginning of a social revolution that evolved through camp in the 20th century.

In a burgeoning age of consumer culture, everyone could buy the feeling of being Unlike-Other-People

Punch found the styles of Decadence pretentious and queer, but there is no such thing as bad publicity, and Decadent and Decadent-adjacent designs became popular. In the gathering momentum of the New Woman Movement in the 1880s, Decadent styles and motifs became a declaration that another way of being a woman was possible too. In her short story ‘The Yellow Drawing Room’ (1892), Mona Caird’s heroine confuses and alarms a potential suitor with her ostentatious interior design: her very own yellow drawing room. At a time when women were idealised as ‘The Angel in the House’, Kate Chopin depicts a woman’s fantasy of gratuitous pleasure after smoking in the short story ‘An Egyptian Cigarette’ (1900). Lady Diana Cooper, one of London’s Bright Young Things in the 1920s, wrote about its continuing appeal:

There was among us a reverberation of the Yellow Book and Aubrey Beardsley … Swinburne often got recited. Our pride was to be unafraid of words, unshocked by drink and unashamed of ‘decadence’ and ‘gambling’ – Unlike-Other-People, I’m afraid.

In a burgeoning age of consumer culture, everyone could buy the feeling of being Unlike-Other-People, revelling in the world of sensation and exquisite taste. Beardsley was a direct influence on Art Deco design and, as the 1960s began to swing, his style offered a blueprint for how art and lifestyle could come together in youth counterculture for the masses. Antony Little’s designs for the fashion label Biba were inspired by Beardsley’s two-tone illustrations, while John Pearse created a William Morris-fabric sports jacket for Granny Takes a Trip, a boutique on the King’s Road in London. With its large gold flowers against intertwined green foliage, it was a symbol of post-LSD psychedelia. The Beatles’ George Harrison owned one. The allusion to Decadent excess was encouraged by the co-owners of Granny Takes a Trip, Nigel Waymouth and Sheila Cohen, who had a full run of The Yellow Book in their shop and a quotation from Wilde above the door: ‘One should either be a work of art or wear a work of art.’ By the time Beardsley and Wilde appeared on the Sgt Pepper’s album cover, designed for the Beatles by Peter Blake and Jann Haworth in 1967, they were icons of rebellious youth.

To those like Du Maurier and more than a few intellectuals in the century or so that has followed, the stylishness of Decadence looks frivolous, as some of it is. In addition, Wilde’s arrest for ‘acts of gross indecency’ with men and his trial at the Old Bailey in 1895 seemed to confirm what society had long suspected: Decadence was overindulgent and perverted. It wasn’t, or not necessarily. But Wilde’s Dorian Gray was used as evidence against him in court and he was imprisoned for two years.

To choose a truffle instead of an odyssey of pleasure is safer by far. However, to really reckon with Decadence is to look beyond style and outrage, and take seriously its scepticism of the values and ideals we hold dear. The uncoupling of style from realism and off-the-peg values has the potential to creatively disrupt the way we think about ourselves and our values. It offers to set us ‘aquiver’ and it threatens to topple us over the edge. That is its danger but also its value.