The historic achievement of marriage equality in the United States last year threw the 1969 Stonewall uprising back onto the public stage. In hundreds, perhaps thousands of media reports, commentators gave the world a story of gay liberation that, more often than not, began in 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City, when lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people rose up in protest against a police raid on a bar. The uprising marked the start of gay liberation in the US, which reached a historic milestone in last year’s Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v Hodges legalising gay marriage. So, from Stonewall to the Supreme Court – a winning story of a marginalised people demanding their rights from the state.

Except it didn’t happen that way.

Stonewall is important, but not because it initiated the beginning of claims on state rights. In fact, the opposite is closer to the truth: the political fervour of Stonewall launched LGBT people on a much deeper, more difficult journey. They began to rethink the very meaning of political power, ideology, and the role of the government. Instead of turning toward the state for recognition, they often turned away from it. They began to transform themselves, intellectually and politically, in ways that revolutionised how they understood oppression and the meaning of governmental and economic power. Throughout the 1970s, LGBT people theorised about the benefits of socialism in books and pamphlets and critiqued capitalism in the growing newspaper and print culture. In doing so, they also began to redefine their identity and to rewrite their history.

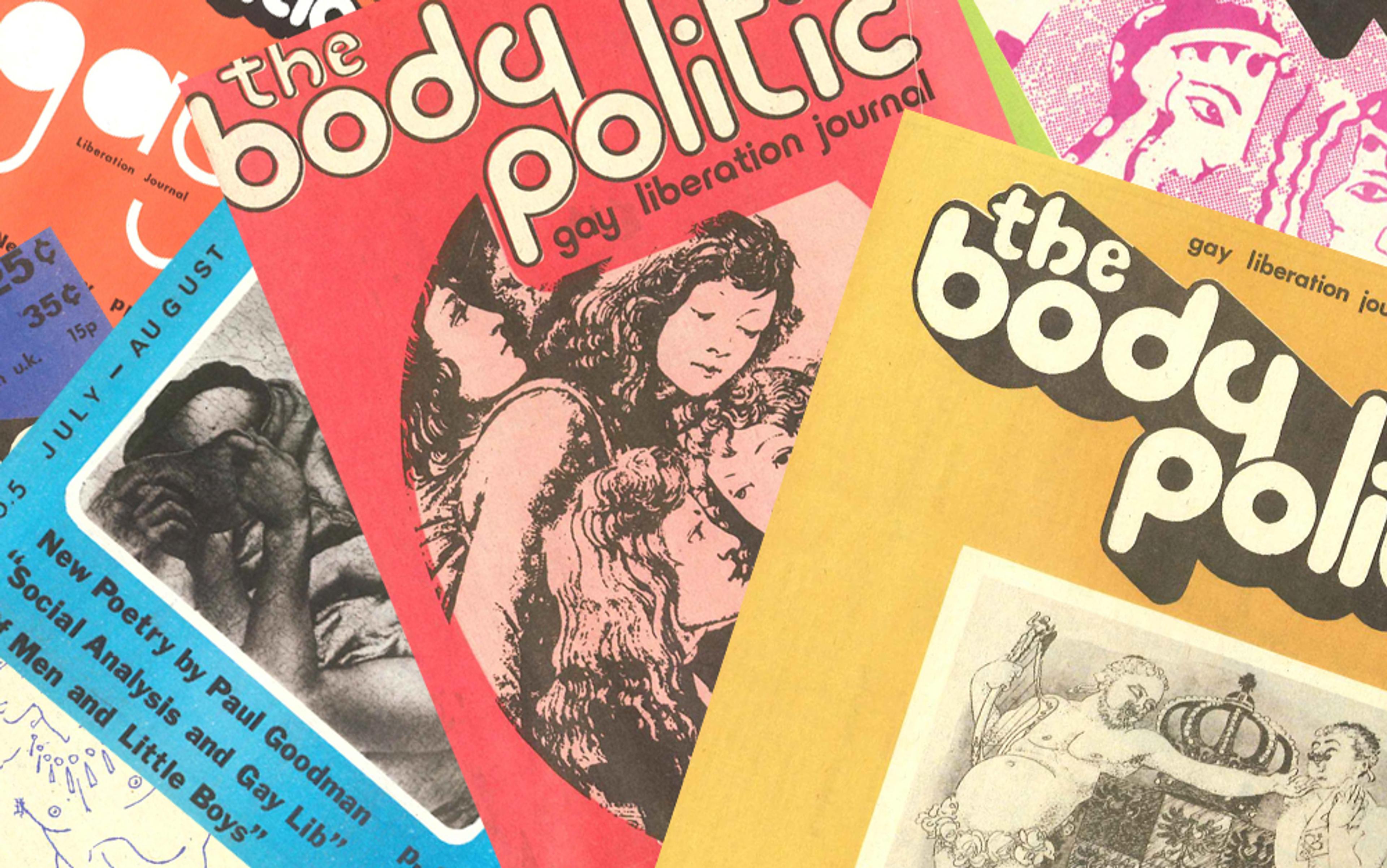

The Toronto-based newspaper The Body Politic emerged in the 1970s as a leading international outlet for gay people to explore the meaning of liberation. With a readership spanning North America and Europe, it was driven by socialist ideas and the examples of the black civil rights and women’s movements in the US. It was an influential and dynamic publication, and also representative of the gay liberation movement.

The Body Politic was particularly interested in how the oppression of LGBT people related to society more generally and its constitutive political forces. It continued to support the fight to end discrimination. But it also had a point of view that saw the cause of oppression not simply in discriminatory laws, but in the power that the government possessed to create those laws in the first place. For example, the article ‘Strategy for Gay Liberation’ (1972) explained that ‘the aim of gay liberation is to root out the source of our oppression’; the point was not to ‘apply band-aids to a never-ending stream of casualties’.

The 1970s saw numerous socialist groups rising to educate LGBT people. Activists offered courses, workshops and reading lists on politics, ideology and society. In San Francisco in 1971, the Gay Sunshine journal republished an essay from the periodical Everywoman to educate readers about how gay liberation needed the support of the working class in order to succeed. ‘While it is important that there be an active political student movement, or an anti-war group, or a gay movement,’ the article explained, ‘these groups, by themselves, cannot change the basis of society because isolated from the power base of society they are impotent.’

The article said that these groups needed ‘the power of the working class’, arguing that the fight against homophobia would be unsuccessful unless LGBT people understood how power operated. In October 1975, the Marxist Institute in Toronto offered a course that would ‘develop from a grounding in the principles of Marxist analysis, through a survey of empirical data available, to an attempt at defining the material roots of gay oppression in class society’. LGBT activists were looking for a structural understanding of oppression, for core insights about how society works, not just reforms to existing laws.

LGBT groups inspired by the Stonewall uprising formed not just in the UK but across Europe, and emphasised socialism as the key to gay liberation

The LGBT fight for equal rights is just one bloom of an intellectual revolution brought about by the LGBT movement’s engagement with socialism. In 1975 in Los Angeles, a group called the Lavender and Red Union formed in the name of socialism and gay liberation. They proclaimed: ‘Gay Liberation is Impossible Without Socialist Revolution; Socialist Revolution is Impossible Without Gay Liberation.’ These were radicals, not reformers.

And they were not exceptional. In New York City in 1971, the Third World Gay Revolution issued the manifesto What We Want, What We Believe, which called for ‘the abolition of the institution of the bourgeois nuclear family’ and ‘a new society – a revolutionist socialist society’. Meanwhile in London, a group of lesbians formed a socialist feminist association called ‘The Lesbian Left’ and published a collection of their papers in 1977. LGBT groups inspired by the Stonewall uprising formed not just in the UK but across Europe, in France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, and emphasised socialism as the key to gay liberation.

These groups both captured and refined a growing determination among LGBT people to learn how power operates and to investigate ways to liberate people from oppression. Gay newspapers, from Gay Sunshine to the nationally circulated Gay Clone (published once a year on May Day to commemorate international workers’ day), made socialism a central subject of their coverage, in articles and book reviews. For a decade, they made socialism a leading subject of political interest in the movement. In the UK from 1975 to 1980, a collective of gay men formed The Gay Left, a socialist journal, which reported on gay people living under communism in Cuba and Russia, and featured articles asking ‘Why Marxism?’ and ‘Was Marx Anti-gay?’

These engagements with basic questions about society formed a deep part of gay liberation, which is portrayed even in relatively sophisticated history books as people in rallies or parades. But throughout North America and Europe in the 1970s, many LGBT people committed to serious engagement with sophisticated, even arcane books about ideology. This phenomenon lay beneath the street activism, and it was a deeply intellectual, often philosophical activity. The Body Politic, for example, included an astonishing number of reviews on the politics and poetics of socialism. The 1 April 1977 issue featured a review of the anthology Gay Liberation and Socialism: Documents from the Discussions on Gay Liberation Inside the Socialist Workers Party (1970-1973). This book was not a narrative history with a plot, characters or storyline, nor even a standard history book with a defined argument or description of events. It was a collection of unedited primary documents of the kind historians immerse themselves in to study and interpret the past.

Such anthologies are almost never reviewed in any but the most specialised scholarly journals. The Body Politic reviewed it, and the writer offered not a basic description or summary of the volume but reviewed it and the socialist movement critically, noting that socialists weren’t able to acknowledge that ‘gay is good’ even as socialism accepted gay activists within the movement as foot soldiers. The reviewer made an argument that Marxists should embrace homosexuality. The very publication of the review and its content reflect an often polemical and forgotten print culture and engagement with serious ideas that infused gay urban community during the height of gay liberation.

This culture of reading and discussion, manifesting in newspapers and journals but also in classes and political associations, brought many LGBT people a newly sophisticated understanding of their oppression. Friedrich Engels’s Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884) served as a lodestar of sorts. It taught LGBT people that the notion of the family was not a natural phenomenon existing across time and space, but rather something that developed at a particular historical moment for specific reasons. Engels argued that ancient societies were matriarchal, and each sex had equal power based on its responsibilities within the home. As time unfolded and men left agriculturally based economies to work in mills and factories, women were forced to attend to domestic responsibilities and their labour lost monetary value.

Engels argued that this was the first sign of oppression and the beginning of class division. While men gained more power as so-called breadwinners, they wanted to preserve their wealth through inheritance, which led to larger class divisions within society. Uncovering the origins of the modern family also proved to be a major insight for the contemporary women’s movement. It explained much of women’s oppression which bourgeois society presented as natural, ancient, unalterable. The history of the modern family as a structure helped LGBT people recognise how economic developments underpinned their own oppression. It also encouraged them to question forms of social organisation that, to most, seemed natural and unchangeable.

In the 1970s, a group of gay men began to meet for spaghetti dinners in New York City every Saturday night. Many of them were writers, scholars, and activists, and during these dinners they would read Engels and Karl Marx, and discuss the implications for gay liberation. Jonathan Ned Katz, a textile artist, was a member of the group. ‘I read every page of Capital and made notes about every sentence. I asked questions. I educated myself by arguing with Marx,’ he told me at his home in Greenwich Village in 2012.

Katz described coming home from the meetings feeling discombobulated from the ‘huge, amazing change’: ‘I was experiencing a change in my self-conception and conceptions of gays in a very short time.’ Growing up, he and the other members had all been taught that homosexuality was a sickness that could be treated by psychologists. Now they were beginning to realise that was not the case. Oh my God, Katz remembered thinking, was I stupid to fall for that idea that I was sick? Sitting on secondhand furniture in a crowded apartment, members of the reading group came to understand that they were not sick, but oppressed, a concept uncovered by reading Engels and Marx. To make that distinction was ‘mind-blowing’, Katz recalled. ‘I would get dizzy and have to lie down.’

The group became known as the Gay Socialist Action Project (GSAP). In it, members learned to see the structures that produced power, rather than refute line by line the pronouncements of priests and doctors who castigated homosexuality. The GSAP discovered that homophobia was less about what a priest declaimed from a pulpit and more about the priest’s power to make his claims; less about doctors labelling gay people ‘degenerates’ in medical textbooks than about the authority with which medics put forth a theory as verifiable truth. The GSAP members came to see that gay people’s alleged aberrance did not make them oppressed. It was that their oppression made them appear aberrant.

Understanding how oppression was done, of course, also brought an exhilarating feeling that it could be undone

Marx and fellow socialist thinkers compelled Katz and others to explore different kinds of questions. Social mores and laws that had seemed unrelated to discrimination came under scrutiny. Just as Engels had shown how the family emerged at a distinct moment in time due to a specific set of economic concerns, Katz and others began to see that homophobia resulted from specific factors at different periods. It wasn’t natural; it wasn’t universal.

Katz realised that different ‘models’ had been developed over time to explain the phenomenon of men being intimate with other men. The first was the religious model, under which authorities meted out ‘harsh penalties’ to those who committed sodomy. He noted that the language reflected the model: religious authorities used the word ‘sodomy’, whereas the medical model – the second model developed – invented a scientific lexicon to describe same-sex relations, coming up with the term ‘homosexuality’ in the late 19th century. By charting how different periods defined same-sex relations, Katz began to see how those in power oppressed gay people. Understanding how oppression was done, of course, also brought an exhilarating feeling that it could be undone.

Katz came to realise that LGBT people had an ahistorical view of themselves. Along with many others who met as part of the GSAP – chiefly John D’Emilio – Katz wanted to correct the misunderstanding LGBT people had of themselves. To do so, he decided to write about the past. The promise of gay liberation, for Katz and D’Emilio, led not only to activism against homophobic laws and discriminatory practices, but also to an intellectual revolution that drove them to write the LGBT history. This wasn’t just history as chronicle or record-keeping. It was a fantastically ambitious intellectual project, the history of LGBT people that would show how power operates in society.

After years of research in the New York Public Library, Katz assembled hundreds of sources that depicted the changing definition of homosexuality in the US, from the colonial period onwards. ‘I moved through libraries like a detective, a tracer of missing persons, following up clues, following trails from footnote to footnote, an explorer in an unknown land,’ he said. He ‘rummaged through library card catalogues and walked through library stacks, pulling out likely books and consulting indexes’. Based on his exhaustive research, Katz at first assembled the sources into a play, Coming Out! (1972), not a book. He thought this would reach a greater audience, and he wanted desperately to provide as many LGBT people as possible with a sense of their history.

The Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), another Greenwich Village association, produced the show. One summer night in 1972, they premiered the play at a firehouse they rented in Soho. A predominantly gay audience sat in a hot, tiny theatre with no air conditioning and not enough seats. Some of the audience sat in the aisle, others crowded together at the back. The play unfolded as a series of monologues narrating gay life in the US from the colonial period to the present. Court cases on sodomy came alive as an actor read an excerpt from a minister’s 17th-century journal. One actor called out: ‘Five beastly Sodomitical boys, who confessed their wickedness.’ Then another appeared on stage as the colonial Massachusetts leader John Winthrop and uttered the word ‘sodomy’. The play took every pathology attributed to gay people and placed it within historical context.

Coming Out! proved a success. A few months after its premiere, it played at the Washington Square Methodist Church in Greenwich Village, and then again at the Night House, a small theatre a few blocks north in Chelsea. It had a profound effect on those who saw it. One audience member proclaimed:

It is a song of life, of gay life. It is a memory of things past, a view of things present, a promise of things yet to be. It is a drama, a comedy, a satire. It is beautiful, it is ugly, it is common, it is rare. It brought many to the point of tears, both from sadness and laughter. It reminded us that we are not alone in our struggle. I cannot find the adjectives to describe what I felt during that evening.

The play’s success won Katz a book contract. Gay American History (1978), a now classic anthology, was the first documentary collection illustrating the complex and changing meaning of homosexuality in the US. Like his play, his book was an immediate success, and was reviewed throughout the gay press. Katz was invited to present his research across North America at gay community centres. He became a leading thinker and writer of the movement. Yet in the present moment of triumph for gay rights, at least in the US, Katz remains a radically under-appreciated figure. The vast and ambitious historical project that grew out of his engagement with socialism remains more marginal than Katz.

Once capitalism created the opportunity for people to live autonomously, it allowed LGBT people to privilege homosexual desire as a driving force in their lives

Like Katz, D’Emilio was a member of the GSAP. In his apartment near Columbia University, where he was a graduate student, he hosted those Saturday-night dinners. Following Katz’s research and the guidance of socialist theory, D’Emilio published ‘Capitalism and Gay Identity’ (1983), one of the most brilliant essays on the history of capitalism in the 20th century. Its insights and challenges have remained radically under-appreciated. D’Emilio masterfully uncovered how the rise of urbanisation and wage labour, combined with the declining role of the family as the major source of economic power, produced conditions that enabled homosexuality to thrive in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As D’Emilio put it, capitalism enabled LGBT to move to cities and to be independent from the family as a source of income. Once capitalism created the opportunity for people to live autonomously, it unwittingly allowed LGBT people to privilege homosexual desire as a driving force in their lives.

D’Emilio’s and Katz’s histories reflect only a fraction of the ways in which socialist ideas informed gay liberation. These ideas also undergirded how LGBT people conceptualised their plight and defined their identity. It provided them with a sophisticated understanding to explore how power worked and, even more importantly, how various historical forces shaped the emergence of homosexuality as an identity.

Beneath and before the street protests and parades of gay liberation lay this intellectual revolution. It was a deep and laborious engagement with ideas and ideologies that made LGBT people advance liberation. In many cases, this revolution led LGBT people to retreat from political confrontations with governmental authorities and from talking about rights. Instead, they used tremendous energies to develop communities and cultivate a culture of their own. The efforts to write about LGBT history was one powerful expenditure of their political capital, talents, resources and intellect. Its goal was not exclusively to change how those in power or in larger society defined them: it was to provide the LGBT community with a sense of their own considerable cultural heritage and legacy.

This is all worth remembering, especially at this moment of triumph for marriage equality. This achievement, not only in the US but also in other parts of the world, has encouraged a popular understanding of the past seeking antecedents for gay people’s political mobilisation. Certainly, gay people throughout the 1970s were engaged in political struggles for rights. But that is only part of the story. The LGBT movement was also infused with socialism, and this engagement led to a reconceptualisation of rights, of strategy, of identity. It changed the gay movement, LGBT people, and the US.

So if you want to give credit for gay liberation and marriage equality, credit must also go to socialism. It was socialism that pushed gay people to an intellectual revolution by which they insisted on defining their own lives and writing their own history.