Law was central to the British colonial project to subjugate the colonised populations and maximise their exploitation. Convinced of its superiority, British forces sought to exchange their law for the maximum extraction of resources from the colonised territories. In The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (1922), F D Lugard – the first governor general of Nigeria (previously governor of Hong Kong) – summed up the advantages of European colonialism as:

Europe benefitted by the wonderful increase in the amenities of life for the mass of her people which followed the opening up of Africa at the end of the 19th century. Africa benefited by the influx of manufactured goods, and the substitution of law and order for the methods of barbarism.

Lugard, here, expresses the European orthodoxy that colonised territories did not contain any Indigenous laws before the advent of colonialism. In its most extreme form, this erasure manifested as a claim of terra nullius – or nobody’s land – where the coloniser claimed that the Indigenous population lacked any form of political organisation or system of land rights at all. So, not only did the land not belong to any individual, but the absence of political organisation also freed the coloniser from the obligation of negotiating with any political leader. Europeans declared vast territories – and, in the case of Australia, a whole continent – terra nullius to facilitate colonisation. European claims of African ‘backwardness’ were used to justify the exclusion of Africans from political decision-making. In the 1884-85 Berlin Conference, for example, 13 European states (including Russia and the Ottoman Empire) and the United States met to divide among themselves territories in Africa, transforming the continent into a conceptual terra nullius. This allowed for any precolonial forms of law to be disregarded and to be replaced by colonial law that sought to protect British economic interests in the colonies.

In other colonies, such as India, where some form of precolonial law was recognised, by using a self-referential and Eurocentric definition of what constituted law, the British were able to systematically replace Indigenous laws. This was achieved by declaring them to be repugnant or by marginalising such laws to the personal sphere, ie, laws relating to marriage, succession and inheritance, and hence applicable only to the colonised community. Indigenous laws that Europeans allowed to continue were altered beyond recognition through colonial interventions.

The rule of law was central both to the colonial legal enterprise and to the British imagination of itself as a colonial power. Today, the doctrine of the rule of law is closely associated with the works of the British jurist A V Dicey (1835-1922) who articulated the most popular modern idea of the rule of law at the end of the 19th century. The political theorist Judith Shklar in 1987 described Dicey’s work as ‘an unfortunate outburst of Anglo-Saxon parochialism’, in part because he identified the doctrine as being embedded within the English legal tradition and argued that the supremacy of law had been a characteristic of the English constitution ever since the Norman conquest. In his germinal Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1889), Dicey noted three key features of the rule of law: firstly, the absence of arbitrary powers of the state; secondly, legal equality among people of all classes; and, lastly, that the general principles of constitutional law had developed as part of English common law, rather than being attributed to a written constitution.

Despite Dicey’s attempts to claim the doctrine of rule of law for the English legal tradition, its earliest formulation comes from ancient Greece. The ancient Greeks contrasted the rule of law positively to the rule of the despot and the tyrannical possibilities of unfettered or arbitrary rule. The doctrine has developed significantly over the past two centuries and can be divided into two main types: formal and substantive ideas of rule of law. Seeking to divest the rule of law from ideas of justice, the formal or thin version of the doctrine is best encapsulated by Joseph Raz in The Authority of Law: Essays on Law and Morality (1979):

A non-democratic legal system, based on the denial of human rights, on extensive poverty, on racial segregation, sexual inequalities, and religious persecution may, in principle, conform to the requirements of the rule of law better than any of the legal systems of the more enlightened Western democracies.

The rule of law was used to give a gloss of moral legitimacy to the colonial enterprise

For formalists, the value of the doctrine lies in its ability to define the lawful authority in any jurisdiction; the constraints that it seeks to put on executive power, and its role in allowing individuals to plan their own lives in light of open, general, clear and reasonably stable rules of governance. On the other hand, modern substantive theories of rule of law associate the doctrine with various ideas of ‘good’, be it democratic government, or protection of human dignity and rights, or notions of liberty. In response to Raz, Tom Bingham noted in The Rule of Law (2010):

While … one can recognise the logical force of Professor Raz’s contention, I would roundly reject it in favour of a ‘thick’ definition, embracing the protection of human rights within its scope. A state which savagely represses or persecutes sections of its people cannot in my view be regarded as observing the rule of law, even if the transport of the persecuted minority to the concentration camp or the compulsory exposure of female children on the mountainside is the subject of detailed laws duly enacted and scrupulously observed.

While they may define rule of law differently, both schools champion its importance both to the state and to the citizenry. I argue that, in the British Empire, the doctrine of the rule of law was similarly championed and used to give a gloss of moral legitimacy to the colonial enterprise. In doing so, it helped to hide the policies of racial and colonial difference that undergirded colonial law and enabled the extraction of resources from the colony to the metropole. Far from meeting the lofty goals of substantive ideas of rule of law, the exercise of legality in the colonies could not even fulfil the prosaic promises of the formalist conceptions of the doctrine.

The British Empire established its earliest colonies in the 17th century in North America and expanded rapidly in the 19th century. At its peak in the early 20th century, it covered a quarter of the world and ruled over 450 million people. Dicey’s exposition of the rule of law was an imperial project and Dicey himself was a frequent participant in the British debates about the empire and its moral and legal responsibilities. He sometimes recognised that the rule of law when imposed by one society on another may itself be ‘arbitrary and oppressive’, however, the doctrine itself, as he understood it, was fundamentally sound. He attributed the discrepancy to the fact that certain civilisations were too ‘backward’ to appreciate its benefits. Despite these reservations, Dicey held a positive view of the British Empire and its commitment to rule of law, and noted that: ‘The one permanent, certain, indisputable effect of English government in the East has been the establishment of the rule of law.’

The British viewed their claim to have established the rule of law as a great achievement and an important benefit of the empire as it spread across the globe. It was central to Britain’s self-perception as a coloniser. Rule of law not only stood in direct opposition to the rule of the ‘oriental despot’, it also distinguished the British from other European colonisers such as the Spanish and the Belgians who were deemed to be brutal and inegalitarian. In practice, the doctrine was reserved for those seen as ‘civilised’ enough by the British imperial officers. When they wished not to extend the doctrine, imperial officials deemed certain communities too backward to merit its application. For instance, most colonised people were denied the right to a jury trial. Further, judges serving in the colonies, far from being independent, were appointed ‘at pleasure’ and were expected to be loyal to the colonial state, with their office being subject to executive removal. Any attempt by them to extend the rule of law to the colonised population against the perceived interests of the colonial regime led to the swift removal of the judge from office. In one such case, the Privy Council advised the removal of Joseph Beaumont as the chief justice of British Guiana in South America in 1868, on the grounds that he lacked ‘judicial temper’ and tended to embarrass the colonial government by criticising their practices against indentured labourers in the colony.

When from time to time attempts were made in the colonies to honour the principle of equality under the rule of law doctrine, these measures were limited. For instance, in the case regarding the institution of taxes in newly conquered Grenada, in Campbell v Hall (1774) almost echoing modern substantive – especially modern, rights based – ideas of rule of law, Lord Mansfield noted: ‘An Englishman in Ireland, Minorca, the Isle of Man, or the Plantations, has no privilege distinct from the natives while he continues there.’ Yet, the widespread practice of slavery across the empire, and other forms of colonial and racial difference belied Mansfield’s premise.

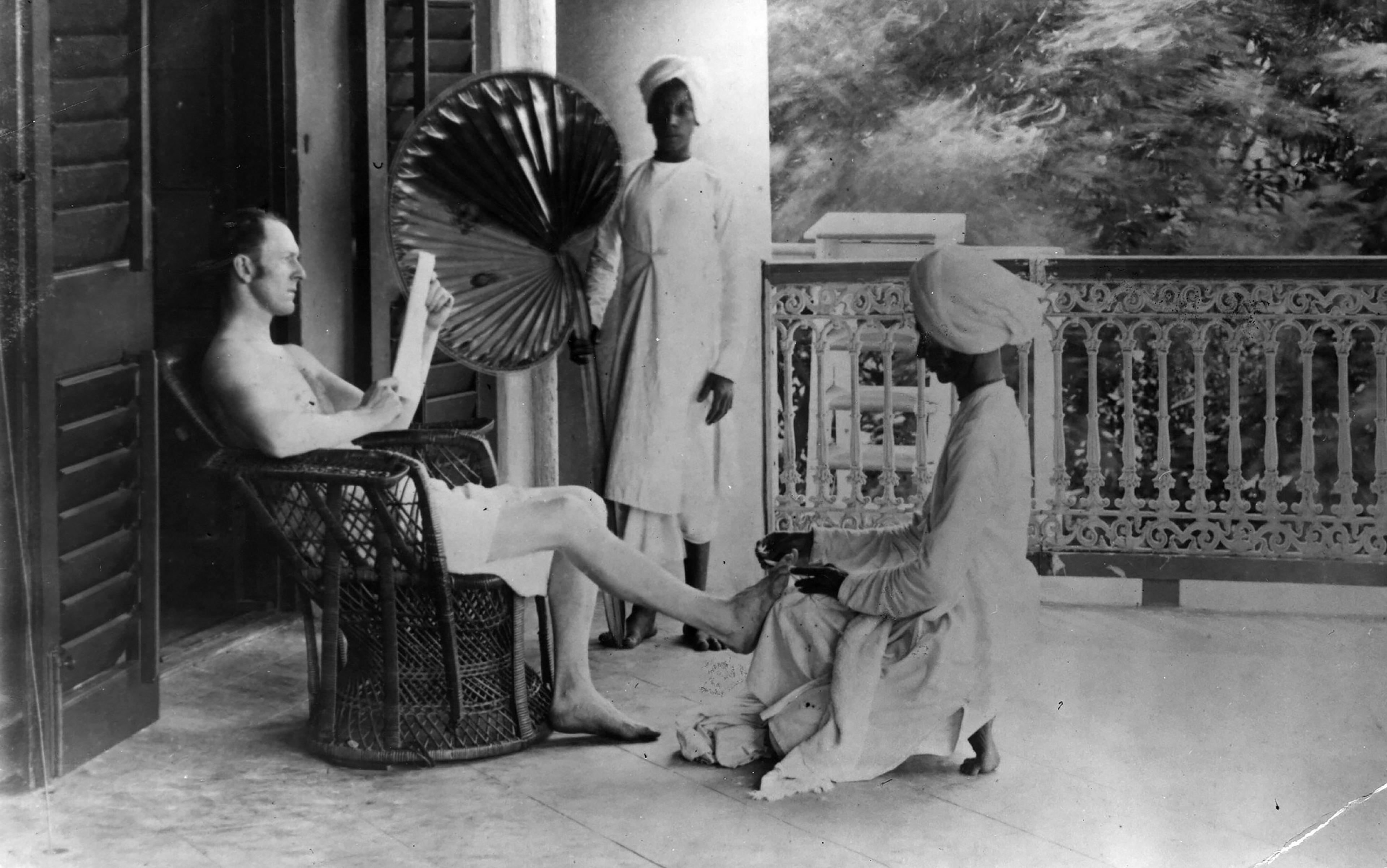

In The Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (1993), Partha Chatterjee posited that the rule of colonial difference underlies all colonial legal systems. That is, despite the supposed liberal ideology of the coloniser, the empire could operate only through a preservation of the superiority of the ruling group over the colonised population. This hierarchy between the coloniser and the colonised was not a byproduct of the system, but the very object that every colonial legal system was created to instil, maintain and justify.

Some were placed outside the ambit of the rule of law while still being subject to law’s coercion

A subject’s race and the so-called dichotomy between the ‘civilised’ and the ‘savage’ were central to the application of law in the colonies. These distinctions were based on ideas of intrinsic physical and biological difference between different populations, with the white Anglo-Saxon man placed at the apex of both the racial and cultural hierarchies. Those who were considered racially ‘inferior’ were also considered to be culturally ‘backward’, with each category serving to reinforce the other. This involved the linking of previously value-neutral physical attributes or cultural practices and assigning to them value-laden interpretations, either positive (as in the case of the ruling races) or negative (as in the case of colonised races).

A stark example of this idea of racial difference can be seen in Lord Sumner’s Privy Council judgment in Re Southern Rhodesia (1919):

The estimation of the rights of aboriginal tribes is always inherently difficult. Some tribes are so low in the scale of social organisation that their usages and conceptions of rights and duties are not to be reconciled with the institutions or the legal ideas of civilised society … On the other hand, there are indigenous peoples whose legal conceptions, though differently developed, are hardly less precise than our own. When once they have been studied and understood they are no less enforceable than rights arising under English law. Between the two there is a wide tract of much ethnological interest …

Race, thus, played an important role in determining the types of rights that were made available to the colonised populations. Based on where they were assumed to be on the ‘scale of civilisation’, some communities came to be placed entirely outside the ambit of the rule of law while still being subject to law’s coercion. At their most stark, the racial inequalities upheld by the empire took the form of slavery that dehumanised the African origin population and remained legal until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 fully came into effect in 1838.

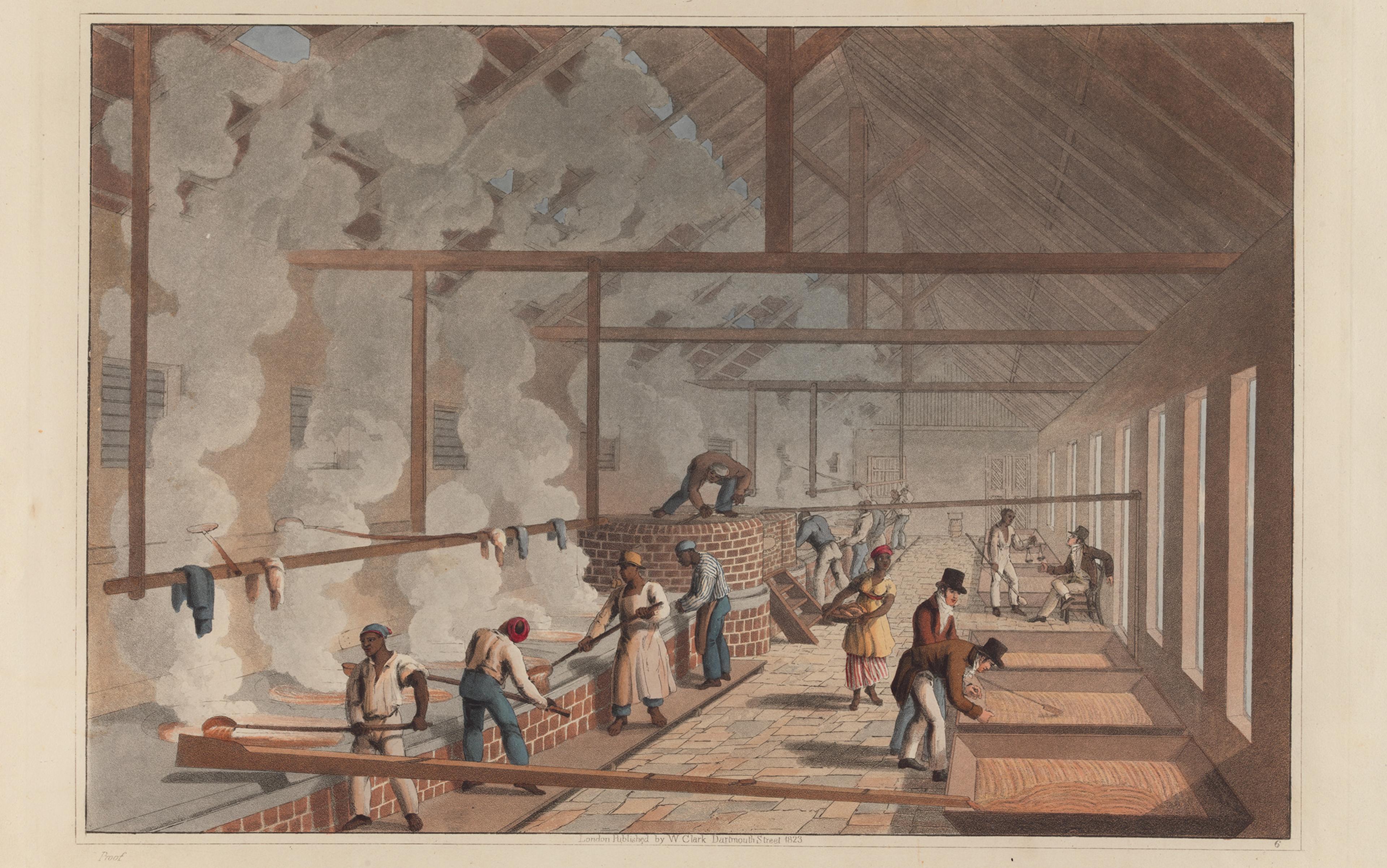

For instance, the slave code passed in Barbados, known as An Act for the Governing of Negroes 1688, explicitly noted that the slave population ‘are of Barbarous, Wild, and Savage Natures, and such as renders them wholly unqualified to be governed by the Laws, Customs, and Practices of our Nation’. This justified the creation of a dual legal system, wherein ‘slave crimes’ were to be tried in slave courts without the benefit of juries. Such laws not only created ‘status crimes’ – ie, crimes that could be committed only by enslaved people, such as being a runaway, abusing a planter/free person, possession of weapons – they also created a dual system of punishment wherein only enslaved people faced brutal punishments that sought to attack their bodily integrity, including flogging, branding, dismemberment and other bodily mutilations. As a result, the dominant experience of colonial law from the enslaved peoples’ point of view ‘was of terror and violence’.

Elsewhere in the world, the Indigenous people belonging to what were described as ‘savage tribes’ in Australia were seen to be inherently outside the law, as were those who were deemed to be ‘hereditary criminals’ under the Criminal Tribes Act 1871 in colonial India. And, in blatant disregard for the doctrine of rule of law, these communities were often collectively punished for any crime by an individual of the group.

By contrast, during the 19th century, white settler colonies came to enjoy some of the freedoms that were seen to be ideologically linked to the rule of law. Across the empire, the colonising population was aware of the privileges granted to them under colonial law and reluctant to see them reduced in any way. Using Chatterjee’s framework, Elizabeth Kolsky argues in her study Colonial Justice in British India (2010) that the notion of rule of law was constantly contradicted by the institutionalisation of racial difference under the law, as well as the overt partiality of legal personnel, including the police, judges and juries. This led to one of the biggest legal controversies in colonial India, when the Ilbert Bill of 1883 was proposed to allow Indian magistrates to preside over cases involving European British defendants. After sustained protest by the white population, the Bill was finally passed in 1884 after securing the compromise of ensuring that they could be tried only by European British majority juries. Of course, similar provisions were not made for the Indian population.

Similarly, in the context of South Africa, Martin Channock argues in The Making of South African Legal Culture 1902-1936 (2001) that the doctrine of rule of law developed in the country ‘primarily along the racial frontiers’ and was used to restrict the rights of African and Asian people in the jurisdiction. He uses the example of the Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 to show how increasingly arbitrary and despotic powers were exercised by local municipalities to remove Black Africans from urban municipal areas, including a regulation that empowered the local superintendent to not only remove people from an area, but to order their huts to be destroyed if they did not comply within 24 hours. And yet, in Tutu and others v Municipality of Kimberley (1918-23) this regulation was found to be neither ultra vires nor unreasonable.

With regards to the Asian population, various economic laws that sought to deny them licenses to trade in South Africa reflected the racial unease of the colonisers. Channock outlines three main concerns: the colonisers worried that the proximity of white housewives to Asian traders in the absence of their husbands may lead to inappropriate contact; that Asian traders extending credit facilities to poor whites may erode racial hierarchies; and, similarly, white women working in Asian shops may lose their sense of ‘racial superiority’. Thus, it is evident that, despite any claims to the rule of law, racial difference was built into the very edifice of the South African colonial legal system and lay the foundations for racial segregation through Apartheid later.

Direct racial discrimination was also apparent in the punishment meted out for crimes. Across the British Empire, the most severe punishments were saved for violence committed by non-whites against the white population. And if the perpetrator was white, punishment for white-on-white violence was a lot more rigorous than the punishment for acts of violence committed by white men against the non-white population. In large part, the latter kind of violence was an intrinsic and normalised part of the colonial capitalist structure that allowed ‘masters’ to have the ‘right of correction’ to brutally beat, flog, mutilate or confine their workers as and when they saw fit. Invisibilised by its omnipresence, routine and indiscriminatory violence by the colonising race remains one of the British Empire’s most closely guarded secrets.

Further, the issue of equal punishment for the same crime for people of different races had always been contentious, and arguments against it focused both on the supposed mental and civilisational differences between the races and their physical or biological differences. For example, in 1844 the legislative member Herbert Maddock argued for shorter jail sentences to be awarded to Englishmen in India on the grounds that ‘the heat of a crowded building surrounded by high walls’ was not at all injurious to the health of the native population but would have a detrimental effect on white prisoners.

Racial discrimination under the law was further entrenched through indirect means by restricting the access of the non-white populations to both legal education and legal professions. For instance, in Tanganyika, in the absence of any local legal training being available, the colonial government required a British law degree to practise law in the territory, while at the same time following a policy of preventing Africans from receiving scholarships to study in Britain. Similar policies were followed by the British elsewhere in Africa, thus, effectively excluding the non-white population from entering the legal profession in large parts of the continent, which no doubt helped to stifle local resistance against colonial law and governance.

Despite the endemic failure of the doctrine of rule of law in the colony, the suitability of the rule and its application were never questioned. Instead, the failure was blamed on the corruption of local officials both white and non-white, or on the backwardness and criminality of the native population. Both this ‘corruption’ and ‘backwardness’ were then posited as reasons for colonial rule to continue until the local population was civilised and advanced enough to accept the mantle of rule of law by itself.

The rule of the colonial powers was anything but stable, open and clear governance

A few key reasons point towards the inevitable failure of any substantive notions of rule of law in the colonies. Firstly, the concept could not overcome its origins. Despite its universal claims, rule of law could not transcend its European social roots and, thus, mostly remained an oppressive imposition patchily enforced when it was of benefit to the coloniser. This links to a second issue: as David Killingray notes in ‘The Maintenance of Law and Order in British Colonial Africa’ (1986), the concept of rule of law remained incompatible with the continuing need of colonial law to oppress and exploit the colonised population. Due to its very nature, the colonial state needed to possess autocratic powers: ‘Government was usually by decree or proclamation, while a battery of laws and reserve powers were directed at the maintenance and preservation of the colonial order.’ Thirdly, racial discrimination within the colony further weakened the commitment to rule of law. Indeed, as we have seen, despite the rhetorical stance of legal equality, legal practice and conventions awarded distinct privileges to the white population and frequently tolerated, and even excused, white violence against the non-white population.

Setting aside the substantive ideas of rule of law, the evaluation of the formalist notion of the doctrine in the British Empire also points to the failure of rule of law in the colonial setting. Within formalist ideas of rule of law, the thinnest conception of the doctrine takes the form of rule by law. Rule by law is the idea that law is the means by which the state conducts its affairs and, thus, easily collapses into the notion of the ‘rule by the government’. Such a doctrine places minimal limitations on state power, save seeking to offer protection to citizens and communities by restricting unfettered or arbitrary rule by the executive. Yet, even formalist notions of rule of law were regularly undermined by the frequent suspension of civil law through the invocation of autocratic martial law under which the colonised people’s already limited freedoms were further restricted and the rule of the colonial powers was anything but stable, open and clear governance. Across the empire, the British frequently resorted to martial law from the 19th century onward, especially in response to popular movements such as the Demerara slave rebellion of 1823 (in modern Guyana), the Indian Uprising of 1857, and the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya in the mid-20th century.

Despite the obvious flaws in the rule of law doctrine in the British Empire, the discourse encountered an unexpected twist in the 20th century. As the struggle against colonialism intensified in Asia and Africa, British officials’ lack of commitment to rule of law in the colony came to be branded by the anticolonialists as ‘un-British’ and condemned as the ‘lawless law’ of British rule. On one hand, the idea of rule of law was denounced as simply being a veil to cover the colonial and capitalist exploitation of the colonies; on the other hand, colonised people actively chose to use the concept as a means of legal and political protection, resistance, collaboration and subversion.

Even a scholar such as E P Thompson, a Marxist historian who was critical of law as a device that mediates and reinforces existing class relations, valorised the idea of rule of law in Whigs and Hunters (1975) and described the British contribution to it as ‘a cultural achievement of universal significance’. In fact, Thompson, like others, justified the ‘goodness’ inherent in rule of law by arguing that Indian freedom fighters, including M K Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, had used the idea of rule of law in their quest for Indian independence. However, as critics of the doctrine highlight, it is important to remember that when colonised people couched their own demands for greater rights in the conceptual language of rule of law, they did so as a strategic move to gain legitimacy and visibility for their causes, and not necessarily as a commitment to the doctrine itself.

At the same time, the anticolonialists’ choice to use the rhetoric of rule of law in their own movements, even if it was a choice made for strategic reasons, points to the endurance of some of the ideals associated with the concept. Despite its status quo-ist nature, and complicity with liberal capitalist regimes, the doctrine has come to stand as shorthand for justice, equality and democracy, which were precisely the objectives that the anticolonial struggles of the 20th century sought to achieve. The enduring legacy of the doctrine to both colonial and anticolonial agendas continues in the 21st century, where the promotion of rule of law has devolved into a multi-billion-pound industry. While furthering neo-imperialist global structures, international developmental aid is routinely tied to rule-of-law commitments and is forced upon postcolonies in the Global South; at the same time, resistance movements in these countries seek to use the concept of rule of law to denounce global capitalist exploitation.

This essay draws from Kanika Sharma’s chapter ‘The Rule of Law and Racial Difference in the British Empire’ in the book Diverse Voices in Public Law (2023), edited by Se-shauna Wheatle and Elizabeth O’Loughlin.