After the Second World War, historians asked us to shift our focus from great men to the actions and experiences of ordinary people, to culture rather than institutions. This methodological shift to ‘history from below’ was political, supporting a democratic vision of political, social, intellectual and cultural agency as the Cold War stoked authoritarian impulses in the East and West. It sought to rectify historians’ paternalistic habit of writing about the people ‘as one of the problems Government has had to handle’, as E P Thompson put it, as objects rather than subjects of history. Influential as this trend was, great-man history retained a cultural hold too and, today, the would-be ‘great men’ dominating political stages around the world, however caricature in form, challenge democratic visions of how history has been and should be made. ‘History from below’ succeeded in throwing out the chimera of great men while preserving the chimera of the nation that was the most common excuse for their invocation. Revisiting its origins might reveal why.

Thompson is perhaps the figure most popularly associated with ‘history from below’, specifically his totemic work, The Making of the English Working Class (1963). Expansive as its cast is, its geographical scope is constricting. Though set in the era of British conquest of vast swathes of the world, it barely acknowledges that reality. This is doubly strange, given that Thompson wrote it while decolonisation was forcing Britons to contend with the ethics of empire, and was himself descended from a line of colonial missionaries deeply engaged with such matters. His classic text created an island template for the most progressive British history of the late-20th century, unwittingly legitimising the nostalgic view of ‘Little England’ that has culminated in Brexit. The book’s enormous impact also ironically endowed Thompson with fairly robust great-man status himself, as the iconic historian-activist of his time.

Is there a history from below, or at least a wider genealogy, that might explain the paradoxical political and intellectual event that was ‘E P Thompson’? How does the picture shift if we recall the choir of voices harmonising with his – his working-class students, fellow British social historians such as Raphael Samuel and Christopher Hill, and European antecedents such as Georges Lefebvre and the Annales school? Or the masses of people – including Thompson – whose collective experience of the global calamities of the 1940s forced reconsideration of progress-wrought-by-great-men as the most practical or believable model of historical narration? Even this tentative shifting of scale tends to dislocate Thompson from the provincial fastness of his work. As it turns out, his ‘Little England’ focus was not a case of early Brexitism, or a patriotic move in the aftermath of Britain’s finest hour, or even a function of his belief in the nation as history’s natural subject. Rather, it was a mirage that ossified into an intellectual reality. Recovering the high-stakes global arguments within the Left in Thompson’s time reveals the cosmopolitan concerns behind his English preoccupations, their short-term cultural payoffs and long-term political and disciplinary costs.

The very English Edward Palmer Thompson was born in 1924 in England, not inevitably, as we might presume, but by chance, a few years after his brother was born in India. His is a story of the cosmopolitan Englishman discovering a provincial, working-class England, in a manner recalling the Indian-born George Orwell’s search for redemption from the ‘evil despotism’ of British India among the English working classes a generation earlier. Like Orwell, Thompson’s father Edward John Thompson, a Methodist missionary and literary scholar in India, quit his colonial job in disgust. The First World War had ruptured his faith in the way of life he’d inherited from his parents. He earned a Military Cross for attending to wounded soldiers under fire as a chaplain to British forces invading Iraq but became disillusioned when the British colonised the region, breaking wartime promises to liberate it from Turkish rule. He resolved thenceforth to stand ‘finally & without question, with the Rebels’, for Western civilisation was bankrupt. On leave in Jerusalem, he met his future wife, Theodosia Jessup, daughter of prominent American Presbyterian missionaries in Beirut.

Like many veterans, Edward John wrote poems and a memoir about his war experiences. But his writing took a new turn after 1920 when he and Theodosia returned to India, where their son Frank was born. Edward renewed his friendship with the anticolonial poet Rabindranath Tagore whom he had met fatefully in 1913 on the very night that Tagore learned of his Nobel prize. His circle came to include other leaders of the increasingly popular anticolonial movement: Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and the poet Muhammad Iqbal. The war and the Amritsar massacre of 1919 had disabused these thinkers of any lingering faith in the notion that history was about progress, and the empire its handmaiden. Edward finally resigned from his mission in 1923 and moved to England, determined to wield his pen for the Indian cause. His Indian friends would visit him there – Gandhi with spinning wheel in tow.

The next year, EP was born – in Oxford, because of his parents’ anticolonial pivot. That year, Edward authored a play, Atonement (1924), about an English hero who renounces violence against Indians and adopts a self-sacrificial role. Finally, he turned to history, producing a revisionist account of the Indian rebellion of 1857: The Other Side of the Medal (1925). He undertook it under the paternalistic presumption that ‘Indians are not historians, and they rarely show any critical ability,’ but also, he confided to Tagore, as an ‘individual Englishman’s act of atonement’. The book questioned long-standing myths about the rebellion as a diabolical attack on an entirely benevolent British presence, myths that had powerfully justified harsh British retribution and continued colonial rule. Instead, Edward described the rebellion as an expression of genuine and understandable political protest. The New Statesman praised it for uncovering the ‘policy of terrorisation’ behind the rebellion.

His rewriting of the history of empire in India was his Byronic gesture

Edward’s historical intervention was enabled by his sense of his own duties as a historical actor, cultivated through his intellectual networks. Besides his Indian friends, he wrote in the company of heroic British contemporaries. His neighbour, another war veteran, the poet and classicist Robert Graves, read the book in manuscript. Graves was an intimate friend and biographer of T E Lawrence, famed hero of the Arab Revolt – perhaps the only action hero to emerge from the war – whom he and others compared with Lord Byron, the Romantic poet who’d fought (and died, from sepsis) for Greece’s freedom in 1824. Edward came to know Lawrence, too.

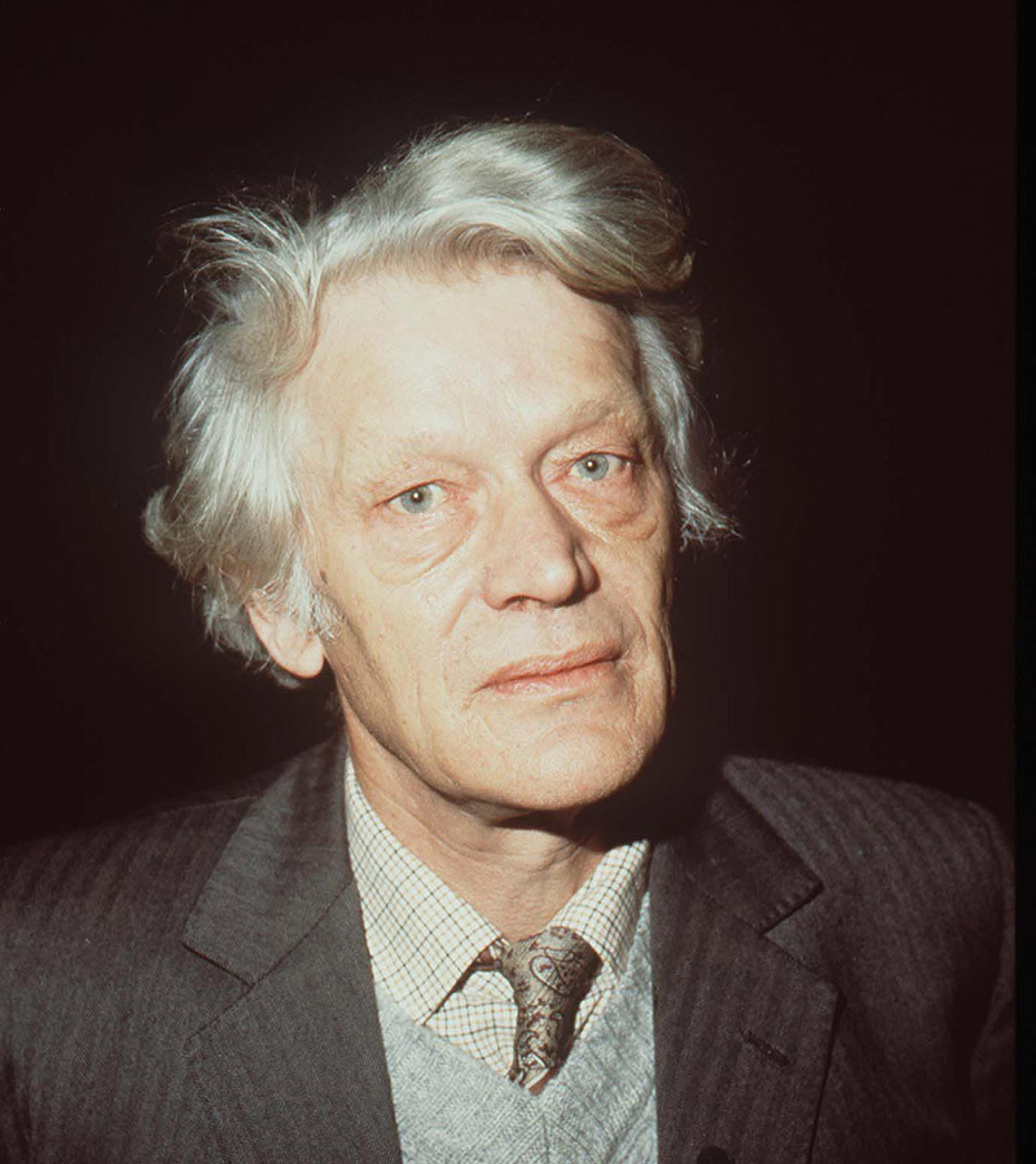

E P Thompson, photographed in 1983. Photo by Hulton/Getty

In this context, Edward nurtured a fascination with the Byronic type – the poet-hero who sacrifices in the name of a beloved enslaved people, redeeming Britain’s sins. In Calcutta in 1936, invoking his own wartime heroism, he wrote to Frank about the way certain individuals ‘get gripped by something that … gives them a sense of destiny which makes them fearless.’ He spoke of heroes who periodically appeared to redeem their country’s bad faith, recalling Byron’s death for the Greek cause, and wondered: ‘Can one man today achieve anything that matters by a gesture?’ His rewriting of the history of empire in India was his Byronic gesture.

It was reinforced by the postwar culture of proactive mass democracy, the idea that citizens must actively check state power to ensure it conformed with their will. Lawrence was a hero but also the archetypal agent of the postwar secret state. If mass democracy’s insistent demand for openness fostered greater official secrecy, Edward offered the historian as the archetype of the active citizen: ‘Now … the historian cannot be historian only,’ he wrote in The Making of the Indian Princes (1943). In a series of works about Iraq and India, he targeted his government’s brutality and the secrecy and propaganda used to conceal it, cultivating a passionate faith in the historian’s craft as a means of truth-telling against the state. The ex-missionary drew on the religious vocabulary of ‘atonement’ to both acknowledge and redeem history from its earlier role as a discourse complicit in empire: ‘Our writing of India’s history is perhaps resented more than anything else we have done,’ he observed in 1943.

Edward’s sons grew up in this atmosphere, with Gandhi, Nehru and Lawrence visiting their Oxford home and their father instructing them in Byronic heroism and the power of individual agency in activism and writing. Nehru gave EP batting tips. EP cadged stamps from the Indian ‘poets and political agitators’ who, he knew, were his family’s ‘most important visitors’. For the Thompsons, it was both the life that poets such as Iqbal and Tagore lived on the front lines of history and their status as poets that made them so admirable. They, too, all wrote poetry (as would EP’s son).

Both Edward’s sons were cosmopolitans. Both toured Greece. During the next world war, EP gave a talk on the Indian nationalist movement at Cambridge. Both served abroad. Frank was in intelligence in the Middle East before he was killed in 1944 during a Lawrence- and Byron-inspired Special Operations Executive mission to connect with Bulgarian partisans in Serbia. This shattering death cast a long shadow over EP’s life. His first published prose was about Yugoslavian partisans. In 1947, he commanded a British youth group assisting the People’s Youth of Yugoslavia in building a railroad from Slovenia to Sarajevo. Thanks to his father, EP had grown up ‘expecting governments to be mendacious and imperialist and expecting that one’s stance ought to be hostile to government.’ Frank’s death fortified that outlook. After his father died in 1946, EP inherited the family struggle to solve the mystery around his brother’s death in the face of the ‘British anti-historical device known as the Official Secrets Act’ and concluded that ‘reasons of state are eternally at war with historical knowledge’.

As decolonisation unfolded, Lawrence’s image became embarrassing to the Left, both his role as paternalistic liberator and covert imperial agent. Though his story and Edward’s fight for India had inspired Frank’s aspirations in the Balkans, EP recoiled at the suggestion that Frank was any sort of ‘Lawrence of Bulgaria’. His father’s liberalism – he advocated dominion status rather than full independence for India – was likewise a liability. EP described him harshly:

It is as if he wishes both to challenge with his pen the imperial power whose rule provokes emergencies, and yet to reassure the rulers that, at the point of emergency, he could be counted on to take up a rifle with the best.

The historian Eric Hobsbawm said that EP was ‘embarrassed by his father’ in the early 1960s.

Still, EP didn’t shake off the understanding of radical struggle as a bond between a penitent Englishman and an enslaved people; he had been raised among great men attempting to make world history. In this anticolonial atmosphere, he channelled those Byronic ambitions domestically in a manner that upended the very idea of great-man history. Significantly, his wife, the historian Dorothy Thompson, had long been researching the life and work of Ernest Jones, the gentlemanly Byronic leader of the 19th-century working-class movement, Chartism. Against Perry Anderson’s understanding of intellectuals as theoreticians – rather than builders – of radical movements, EP defended the ‘typically English notion of radical intellectual practice based on the widest possible interchange between intellectuals and workers,’ writes Dennis Dworkin. Intellectuals’ place was ‘“inside” the struggle’, articulating ‘the experience and aspirations of the subordinate classes’. This Byronic positioning within British socialism was also EP’s reaction to the intellectual disenchantment that he traced to Orwell’s essay ‘Inside the Whale’ (1940), which had vaunted a kind of noncooperative quietism in the face of total violence. ‘We must get outside of the whale,’ EP implored in 1978.

EP rummaged through lost causes as an end in itself, to redeem what had been lost

His Byronism is evident in his stated aim to ‘rescue’ history’s losers ‘from the enormous condescension of posterity’, as he put it in The Making of the English Working Class. But it was also manifest in the contemporary political goals driving his historical work. He wrote the book while instructing students at the Workers’ Educational Association in their historical agency, leading the popular Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), and establishing a ‘New Left’ in Britain. The war, and its end in the atom-bombing of Japan, had sharpened EP’s inherited suspicion of the progress narratives that had justified colonialism. ‘Our only criterion for judgment should not be whether or not a man’s actions are justified in the light of subsequent evolution,’ his book admonished. ‘After all, we are not at the end of social evolution ourselves.’ Crucially, he hoped ‘lost causes’ of the past might yield ‘insights into social evils which we have yet to cure’. EP’s sensitivity to ‘lost causes’ recalls Walter Benjamin’s insistence on the eve of his death in 1940 that ‘nothing that has ever happened should be regarded as lost for history’ as well as his hope that a ‘redeemed mankind’ might experience the ‘fullness of its past’. In 1931, the devoutly Methodist historian Herbert Butterfield had also debunked the foundational idea of the ‘Whig interpretation of history’ – that the job of historians was to dispense moral judgments upon people of the past.

After the Second World War, Butterfield argued that history’s only possible meaning lay in ‘something in each personality considered for mundane purposes as an end in himself’. The German historian Reinhart Koselleck, similarly diagnosing the way in which inherited philosophies of history had encouraged a habit of viewing ‘the present and the past from the perspective of a redemptive future’ (as Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann writes), maintained that history has no direction or meaning. But EP clung to the idea that history offered insight into ‘evils’ that had future cures, that ‘social evolution’ had an ‘end’. For him, recovered utopian notions – causes that were not so much lost as unrealisable by nature – were necessary for practical politics, permitting ‘critical assessment of the present in terms of some deep moral commitment’ and unleashing ‘imaginative longing for a particular kind of future’, as the historian Joan Scott explains. EP rummaged through lost causes as an end in itself, to redeem what had been lost, but also more pragmatically to recover ideas that might further progress in his time.

Specifically, EP hoped that the creative ideas of radical 18th-century workers might offer an alternative to the uninspired conformism demanded of the deterministic historical vision of the Communist Party of Great Britain. The Soviet Union’s brutal crushing of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 seemed to confirm the Marxist historical imagination’s hijacking in service of authoritarianism. Moreover, as its apparent connivance in his brother’s death seemed to confirm, the British state behaved no less imperiously, even while decolonising abroad: ‘Inter-recruitment, cross-postings and exchange of both ideology and experience’ meant that methods designed to pacify crowds and invigilate subversives abroad were now applied to the disciplining of the unemployed, women and crowds at home. The radical William Cobbett loomed large in The Making of the English Working Class, for discerning a system of corruption that Cobbett called ‘the Thing’. EP wrote the book in 1963 with an eye on the Cold War warfare state, which in 1965 he would dub ‘this new Thing’: a ‘new, and entirely different, predatory complex’ of military industry and the state. His sense of his role as historian truth-teller, like his father’s, was shaped by a perception of imperial abuse – this time, at home. His work was thus anticolonial, despite its domestic focus. He looked to the history of the English working class to guide Britons out of the imperial darkness of the ‘secret state’ and hoped that a ‘New Left’ might recover more democratic forms of revolutionary agency.

The imprint of his childhood among anticolonial poets and his father’s generation of war poets, evident in his Romantic sense of his own agency, also manifested in his insistence on poetry’s importance to liberatory politics. EP and his father drew on their vestigial belief in the potential for heroic action to question the imperial, great-man historical imagination that had given them that belief. In doing so, they helped imagine a new kind of history and history-making, infused with a poetic vision.

Such were the cosmopolitan and anticolonial roots of E P Thompson’s remaking of British social history. But the very context of decolonisation effaced them from view. In the 1950s, signs of a decisive end to British imperial power accumulated, culminating in the Suez Crisis of 1956 (just when the Soviet Union crushed the Hungarian revolution): an abortive invasion of Egypt that exposed Britain’s subordination to the United States, bringing down the government of Anthony Eden and puncturing hopes that decolonisation might not entail substantive change in Britain’s relationships with former colonies. Talk of ‘decline’ escalated, albeit in a decade of affluence. Despite this context, despite his cosmopolitan experiences and early writing, despite his family history, The Making of the English Working Class scarcely glanced further than France – though the radicals it talks about were hardly insulated from British activities abroad.

Embarrassment was certainly a factor, we have seen. But more practically urgent was the desire to remake and redeem British identity in this time of decolonisation in terms of the communitarian values of the working class – rather than the long-vaunted paternalistic values of the (imperial) ruling class, as Orwell had done in the time of fascism. EP’s book was in this sense completely shaped by the context of decolonisation, however silently. From the Age of Revolution that was his subject, rebellion abroad had influenced British radicalism. Post-Second World War anticolonial rebellion likewise ruptured British thought and activism.

EP wrote the book in the shadow of anticolonial disillusionment with the West. Shortly after he and the Jamaican-born cultural theorist Stuart Hall founded the New Left Review in 1960, he left in high dudgeon as devotees of theoretical history took over the editorial board. He particularly objected to the journal’s adoption of a ‘Third Worldism’ in which ‘the entire “West”… stands impeached by its complicity with colonialism,’ as he wrote in his (only recently published) resignation letter in 1963 – the year that The Making of the English Working Class was published.

Affirming the identity of interests of peoples across the alleged West-Third World divide, EP addressed the judgments of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961), which, like Tagore and Gandhi earlier, cautioned forcefully against ‘mimicry’ of a West whose culture and institutions were manifestly morally and practically bankrupt, with Europe headed ‘into the abyss’. Sympathetically conceding that the text’s context made it ‘not only comprehensible but inevitable’, EP nevertheless fervently contested the conclusion that the ‘West’ had ‘nothing to offer’. His effort in his work to recover alternative ‘English’ values – radical humanistic ones – was partly in a spirit of defiant redemption. ‘For us,’ he explained, ‘the “European game” can never be finished’: ‘If “our” tradition has failed … then it is for us to put it in repair’ rather than hastily conclude that ‘the humanist values discovered in the West are corrupted beyond recall’. He strove to discover a different possible England whose values didn’t lead ineluctably to empire.

This radical English inheritance was also his answer to his rivals’ provoking caricature of an ‘English ideology’ – inveterate traditionalism, empiricism and provincialism that, they alleged, had kept England’s working class overly docile and subordinate and the intelligentsia hidebound and dilettantish, unlike in ‘Other Countries’. EP immersed himself in ‘The Peculiarities of the English’, as he titled his 1965 essay on this dispute, partly to defend their radical patrimony, the ‘revolutionary inheritance’ that was ‘the tradition of dissent’. We know that those values were shaped through engagement with other traditions, as EP’s own radical values had been. He knew this too, criticising his adversaries for assuming ‘hermetic divisions between national cultures which are quite unreal’. But since England’s redemption was at stake in this debate, it was his focus. The stakes for recovering the at once communitarian and libertarian values of the specifically ‘English’ working class were high: the redemption of Britain’s humanistic and radical values.

Still, there remains a whiff of imperial nostalgia in the provincial focus. EP’s resignation letter also defensively rehearsed liberal pieties about British imperialism having always been headed towards self-government. His well-known condescension towards religion – particularly working-class Methodism – echoed liberal historical assumptions about the way that religion stymied progress, so central to the colonial endeavour. Indeed, whatever his awareness of the cultural costs of ‘progress’, he remained invested in the idea of universal history, assuming the 18th-century British story was a harbinger for what would evolve everywhere. In his celebrated 1967 essay on time, he avowed:

Without time-discipline we could not have the insistent energies of the industrial man; and whether this discipline comes in the form of Methodism, or of Stalinism, or of nationalism, it will come to the developing world.

His leadership of the CND likewise betrayed a hope that Britain might take a great, redemptive role in leading the world. After all, lurking beneath the iconic gerunding of his book’s title was the inspiration of his father’s last historical work, The Making of the Indian Princes. Decolonisation is not an instantaneous process; it takes generations.

India was ‘perhaps the most important country for the future of the world,’ he declared

The cosmopolitan allegiance that EP most readily claimed, according to his wife Dorothy, was to the peoples of Europe – despite family ties to the US, the Middle East and South Asia. Still, he felt a ‘continuing relation to Indian culture’ as a ‘legacy from my parents’. His father’s advocacy for India was at least redeeming vis-à-vis their earlier Methodist commitments. EP eventually publicly owned this inheritance with the at once humble and distancing frame of ‘alien homage’ – the title of his 1993 book on his father’s friendship with Tagore.

In 1976, a momentous six-week visit to India during the Emergency under Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi pivotally fuelled the vehemence of his scathing essay ‘The Poverty of Theory’ (1978) and undid his usual embarrassment about his father. On arrival, EP was warmly welcomed in acknowledgment of his father’s friendship with the late prime minister Nehru. He put on tape his childhood memories of Nehru. He was quickly dismayed, however, to witness the extent to which Indira had abandoned her father’s democratic principles. Worse, the Moscow-directed Communist Party of India supported her repressive measures, obligingly coining theoretical abstractions to justify the Emergency’s abuses. The visit left him profoundly disturbed by the convergence of Western modernising theory – an updated version of the liberal progress narrative – with Moscow-directed socialist theory: both envisioned an intellectual elite imposing progress upon the nation through top-down, capital-intensive, technologically driven development. Both, to him, were vulgar in their unpoetic political vision.

EP recorded his impressions in an unpublished document titled ‘Six Weeks in India’. But after Indira’s fall in 1977, he described his Indian visit in The Guardian in 1978, speaking as the proud son of his father while he publicly shamed members of the British Left for having supported the Emergency out of misguided loyalty to Indira as her father’s daughter. India was ‘perhaps the most important country for the future of the world,’ he declared, ‘a country that merits no one’s condescension.’ He foresaw ‘unpredictable and creative things’ in its future – as long as it averted authoritarianism. ‘There is not a thought that is being thought in the West or East which is not active in some Indian mind,’ he concluded – the spirit of dissent that he so valued and had been exposed to through Indian thinkers as a child.

That EP’s extended thoughts on the postcolonial world appear in two unpublished documents perhaps reflects a deliberately humble effort to be silent about regions for which Britons had too long illegitimately claimed to speak. But whatever his implicit cosmopolitan and anticolonial commitments and explicit progressive goals, EP’s ‘Little England’ focus proved a liability for the discipline, for its sticky provincial portrayal of a deeply cosmopolitan era in British history. We are still recovering the lost dimensions of that story. Such provincialism alas abetted the narrowly national history curriculum assembled under Margaret Thatcher, facilitating British amnesia about empire today. Hall protested in 1988 that national frames cannot serve us; colonial history has made it impossible to conceive of specific communities and traditions with settled and fixed boundaries and identities. EP’s parochial framing of British social history in his search for redemption from imperialism ironically enabled denial of precisely those transnational bonds.

In fact, the making of the English working class was inseparable from British activities in India – which kept demand for mass-produced military goods high and provided the handmade cottons that British industry strove to imitate. The industrial revolution that produced the English working class simultaneously ruined the Indian handloom textile industry. Yet, taking Thompson’s airtight English story as an ideal, historians wasted decades searching futilely for its analogues in the very place upon whose ruin its formation depended. We are only now beginning to grasp that subjectivities elsewhere in the world were shaped in different directions by the very historical processes that produced the English ‘norm’.

The idea of ‘history from below’ is that great-man history wrongly credited singular heroic actors with history-making power. Its emergence depended, ironically, on the Thompsons’ own sense of great-man capacity to change history through their intellectual labour. The family’s compulsive paper-hoarding testifies to their awareness of their historic ambition and importance. So too does EP’s taste for dramatic action and his signature ‘Byronic’ mane. An inherited sense of historic destiny, shaped in the era of colonialism, emboldened EP to radically change how many consumers and writers of history understood its purpose. A prominent strand of British history-writing promised to fulfil morally and politically redemptive democratic ends, a purpose wrought of anticolonial connections and conversations. If EP’s provincial focus obscured those motivations, the power of connection itself, with all its openendedness and transnational germination, remained central to his radicalism – a universal humanistic value helpful to recall as authoritarianism hovers over the Indian subcontinent and Britain rushes to destroy its bonds with the European one.