So, let us assume that you have either moved to the country or have been there for a while. In your new/old haven/hovel is either a log-burning stove or an open fire. Since it needs fuel in order to work, there are a couple of options available. Either you can buy a big bag of damp logs from the local garage that will smoulder and pop, or you can buy an axe. Striding confidently into the local ironmongers, you ask for their finest, sharpest blade. They offer up something slim with an American hickory haft. You stride out again, feeling somehow that the mere possession of this perfectly weighted prize has made all your atoms flow in more vivid order.

Three days later, having spent the intervening time rolling around a sawdust-covered floor with half a tree attached to your left foot, you return to the ironmongers and ask humbly for something that works. This time, they sell you something with a much fatter wedge-shape, like a slice of steel cake. This time, it’s heavy, and this time it doesn’t look like a murder weapon but a proper working tool.

Back in the shed, you select a log about the same diameter as your wrist. When you place it on the chopping block and swing the axe, it cleaves like a slit envelope. You pick something slightly larger. That too opens as if it had been waiting for the instruction to do so. At the end of an hour, you have a pile of perfect triangles, their heartwood pale in the winter light. Your back aches like it does after gardening, but you feel three times the being you were before.

There is something so simple about chopping logs that it feels like a form of mending. You find that if you yourself are balanced, it needs neither great physical strength nor limitless energy. If you swing it in the right measure and trust it to do the job for which it was made, then the axe, rather than you, will split almost anything you set it to.

Perhaps the most elusive thing to learn is how to stop making life difficult for yourself. Pick the right wood, don’t be over-ambitious, pace yourself. Certainly you can make it more complicated — the secrets of branches, the crosswise chop, the challenge of burs — but there’s no need to. Instead, it’s lovely just being there, standing straight, swinging slowly. After a while, you build up a rhythm: place the log on the block, stand, breathe, swing, cut, place, stand, breathe, swing, cut.

Skip-diving has its charms. There’s a kind of melancholic fin-de-siècle splendour in torching your neighbour’s kitchen

If necessary, you can use chopping logs as a vent: it’s the phone company, or it’s the British weather, or the pillock from work. It doesn’t much matter, since taking out rage on a lump of elm is undoubtedly better than taking it out on the pillock from work. A Canadian friend has a corporate solution: he would set up chopping ranges for rurally frustrated executives in New York or London. They could arrive after work, rent a cord of wood and an axe, find their block along the numbered line, and start swinging. They’d be free to keep going either until their cord ran out or the muscles in their jaw stopped twitching. If they wanted to buy them, the chopped logs would be theirs; if not, they’d be bundled up and sold on.

Personally, I just like chopping for its own sake. There’s something warming about the ritual of it and the sense of provision. Place, stand, breathe, swing, cut. Watching the wood. Watching the radial splits out from the centre, marking the place to bring the axe down, waiting for the faint exhalation of scent from the wood as it falls. Like cooking, it provides a sense of sufficiency and delight but, unlike cooking, log-chopping has a particular rhythm to it, like a form of active meditation. You do, very literally, get into the swing of it.

Occasionally, splitting elm or beech, patterns emerge. Spalted logs have black lines like the lines that divide sea from land on maps, so when they open it’s like a whole world offered up for burning. Ash cuts white. Pine glows red in the centre. Oak (should you be lucky or crazy enough to be chopping it up for firewood) feels like substance itself, while elm seems almost supernatural. It behaves like some other element — as if it’s got no grain, as if it’s paper or stone.

If you’re lucky, the logs you’re splitting are already dry. Or dryish. If they’ve been lying outside getting dripped on, they’re probably so saturated they’re treble their dry weight and, even after the 10 years it will take to dry them out, they’ll almost certainly burn with the same vigour as mouldy towels. Only ash burns straight off the tree; everything else has to be seasoned. One of the downsides of a damp country is that wood takes many times longer to dry out here than it does in, for instance, somewhere nice. Rule of thumb is about a year from felled tree to fire for hardwood and six months for softwoods.

On the other hand, such awkward odds encourage ingenuity. Once you’ve satisfied the immediate need for something to keep you warm, you start building a log pile. This too has its craftsmanship: a place to put them where the wind can get them but the rain can’t, a question of balance and, when it’s done right, a thing of beauty. It takes patience and a feel for the way things weigh and join.

In Scotland, where there is a constant year-round need for heat, people take pride in their log-piles. They become not just fuel-caches, but interesting clues to character. Like squirrels, some people prepare for winter months in advance, building long free-standing log walls. Some neighbours have gone the full Paul Nash and constructed beautiful free-standing beehives. Others sling a heap from the local sawmill into the garage, or stockpile like it’s the Siege of Leningrad. Most don’t really care how it’s done as long as it stands up and stays dry.

For the dedicated accumulator, there’s also the stuff you can get out of skips — old fence-posts, knackered studwork, abandoned flooring. As long as you don’t mind wandering down the local high street with half a door under each arm, then skip-diving has its charms. The wood’s usually dry and there’s a kind of melancholic fin-de-siècle splendour in torching your neighbour’s kitchen. The downside is that you’re probably going to have to spend three weeks sawing it into grate-sized pieces; the upside is that you’ll get warm while doing it.

It’s the final stage of log-chopping that stops me. In theory, it would be possible to get a chainsaw certificate and progress to whole trees. In practice, I don’t want to. Not because it wouldn’t be interesting or useful, but because a chainsaw just seems a bit too butch. I like being female, and somehow the idea of staggering around the forests of Scotland brandishing a smoking Stihl seems a little overcompensatory.

The point and the pleasure of chopping logs is that it is just me and a stone-age tool. Standing there in the shed in a deep layer of sawdust and chippings, I can hear the birds and the river and the changing note of the blade as it strikes different ages and sizes of timber. I can sense the rhythm of my own work and the difference between old wood and new. A really good chainsaw user can probably tell beech from chestnut and sitka from larch while blindfold, but somehow there’s no fun in that fretful roar and the reasonable fear of decapitation.

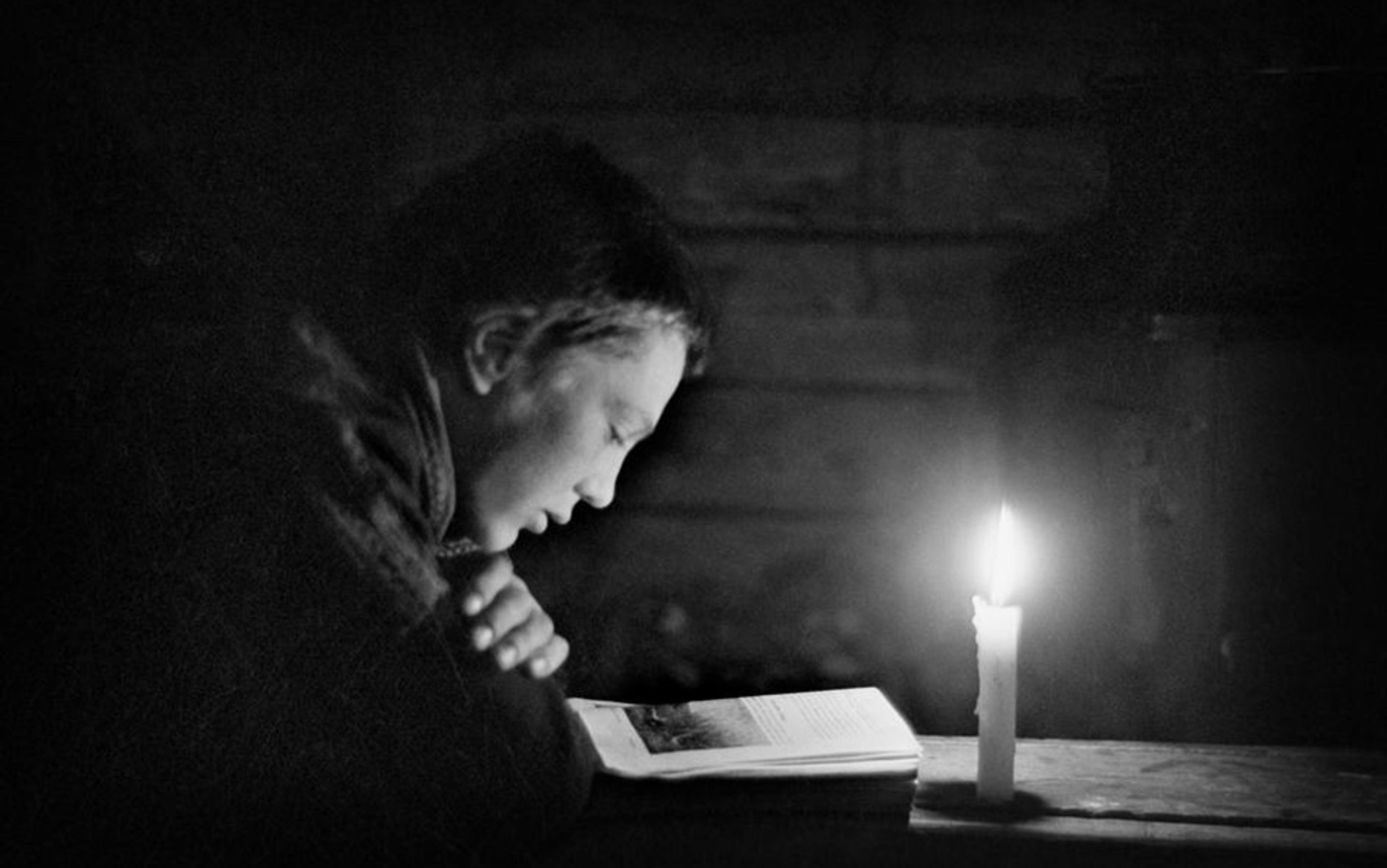

In the end, it doesn’t much matter. All that matters is that when it’s January and blowing a gale out there, I can walk through the darkness, stack up a scented armful, and make true fire.