If asked, most people in the West would say that wicked witches who fly unaided or turn into animals don’t really exist. And, according to all available evidence, they would be right. It’s more difficult to prove that no one practises ‘witchcraft’, that is, conducts rites or utters curses in an attempt to harm others. Yet regardless of what people say about witches, or even what they believe, the idea of the witch is a universal constant looming over cultures from the islands of Indonesia to the pizza parlours of the modern United States.

Fifty years ago, as graduate students at Oxford, my wife and I were preparing to do anthropological fieldwork on the island of Sumba, in eastern Indonesia. Not long after beginning our research, an elderly ritual expert happened to mention that yet another ritualist – one of his rivals, as it later turned out – had ‘eaten’ a woman, the wife of a third man. This took me aback, in part because the woman in question was still alive. But I soon learned that the old man was accusing his rival of being a mamarung, a witch, who on Sumba is said to cause illness and death by invisibly eating people’s souls. Meeting secretly at night, Sumbanese witches also capture human souls, transform them into sacrificial animals, and then slaughter these to kill their victims and consume their bodies.

Thinking about this after returning to the United Kingdom, I realised that the same accusations of ritual killing and cannibalism were levelled during the ‘witch crazes’ of the early modern period, from the 14th to 17th centuries, in Europe, resulting in the persecution and killing of many of those accused. European witches were also said to feast on human flesh, transform themselves and others into animals, join nocturnal assemblies, and fly through the air. Far more recently, I was reminded of the universal idea of the ‘witch’ by Pizzagate – the QAnon conspiracy theory that Hillary Clinton and other members of a supposed global elite were killing and eating children in secret satanic rites, conducted while operating a paedophile ring in a pizza parlour in Washington, DC. As I read further, I realised that the Pizzagate accusations were recycled versions of allegations levelled during the 1980s and ’90s against owners and employees of US daycare centres who were identically accused of sacrificing children and eating them.

But what is a ‘witch’? To prove that a belief in witches really is a human universal, we obviously need a definition. We also need to be clear about what ‘universal’ means. Actually, a definition commonly used by anthropologists, historians and other academics suits well enough. A witch is a human being who, motivated by malice, wilfully harms other people not openly by any physical methods, but by unseen, mystical means. Secret acts of ritual killing and cannibalism – essentially treating people like animals – are typical expressions of the witch’s hatred of humans. For example, witches among the Navaho of the America Southwest were accused of cannibalism, just like witches in New Guinea. Charged with the same horrendous acts, those US daycare workers would simply be seen as a variety of witches. In working through Satan, these rumoured devil-worshippers resemble not only the witches of medieval and early modern Europe, but equally witches described in Africa, Asia, the southwest Pacific, and native North and South America. For not only do non-Western witches kill people and eat them; they are similarly believed to obtain their powers through local demons. To cite one of many examples, Sumbanese witches possess evil spirits called wàndi that they keep inside their bodies and send out at night to attack their victims.

It hardly needs mentioning that I’m talking about ‘wicked witches’, and not the ‘good witches’ familiar to Westerners from The Wizard of Oz, nature-loving Wiccans, or the progressive young women who populate the pages of ‘witch-lit’. Such good witches find an explanation in the history of English, specifically the derivation of ‘witch’ from an Anglo-Saxon word further applied to healers and benevolent magicians. But the important point is that, throughout history and in a great variety of cultures today, people have imagined and continue to imagine thoroughly nefarious figures corresponding to the wicked witch.

Witchcraft reveals our persistent and enduring tendency to imagine the existence of evil people

To say that witches are universal doesn’t mean belief in them has been recorded in all cultures, or that, where recorded, widespread public accusations, witch-hunts or moral panics ensue. Whereas recent accusations of satanism in the West, including Pizzagate, evidently do reveal these features, witchcraft in non-Western societies often does not. For instance, the Hopi people of Arizona never openly accused people of being witches, for fear of retribution. Instead, they believed the evildoers would be punished in the afterlife.

Anthropologists have also described a few societies as being unfamiliar with witches altogether – at least at the time they were being investigated. Or they were familiar with witches but didn’t feel particularly threatened by them, perhaps because they thought they were sufficiently protected by counter-witchcraft magic or the security of benevolent gods. An example are the Tallensi of Ghana, in whose world view the anthropologist Meyer Fortes judged witchcraft to be ‘remotely peripheral’. That is, the Tallensi do not, for the most part, believe that misfortune derives from the wickedness of other people but from the actions of just and all-powerful ancestors, so that illness and death are interpreted as rightful punishment for human wrongdoing.

What the universality of witchcraft does reveal, however, is our persistent and enduring tendency to imagine the existence of evil people, either next door or somewhere in the next valley, who constantly strive to harm us by supernatural means. Thus, the same ideas crop up time and again in places that are otherwise culturally different and geographically distant.

John Pettie Arrest for Witchcraft 1866. Courtesy the NGV, Melbourne.

Seventeenth-century Massachusetts (including Salem) provides the most popularised example of witchcraft. English immigrants, many of them Puritans, faced the challenge of a harsh existence in a new land, surrounded by sometimes hostile native peoples, and riven with religious and political divisions. They found themselves needing to account for both misfortune and the fact that some succeeded while others failed. To do so, they invoked witchcraft beliefs imported from their native England and identified particular neighbours who were reputedly in league with the devil as the cause of their ills. As a result, accusations were made, people were tried as witches, and dozens were executed.

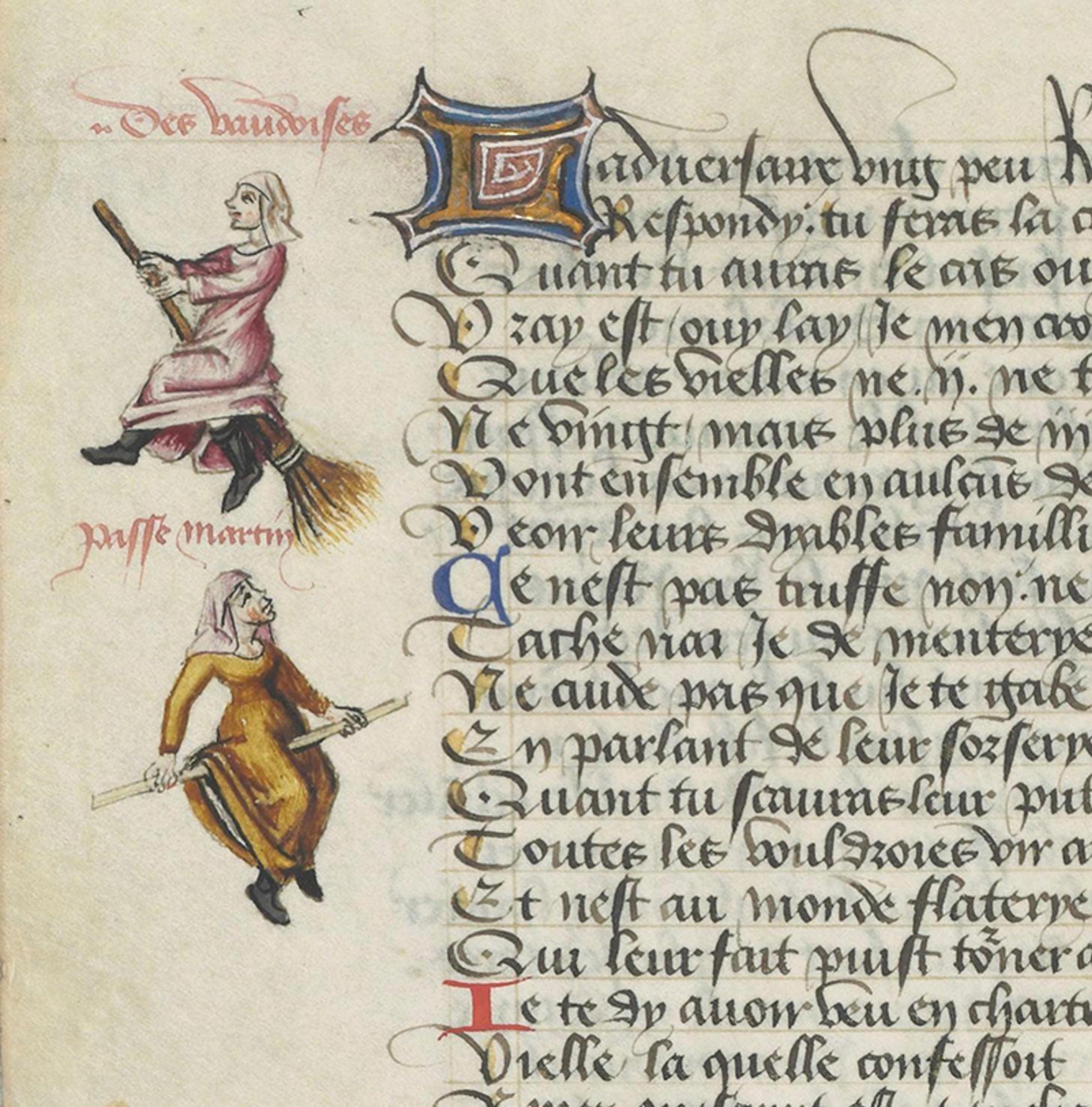

An early illustration of witches on broomsticks from Martin Le Franc’s ‘Le Champion des Dames’ (1451). Courtesy the BNF Paris.

Historians often focus on earlier witch-hunting crazes erupting in 15th-century Europe, after a period of relative indifference. Why did the phenomenon appear so suddenly and then decline with similar rapidity in the 18th century? Both the Enlightenment and the emergence of modern science during that century and the subsequent Industrial Revolution have been invoked to explain this change. Yet historians have recently documented beliefs in witches and malicious witchcraft, especially among rural Westerners, persisting into the 20th and 21st centuries.

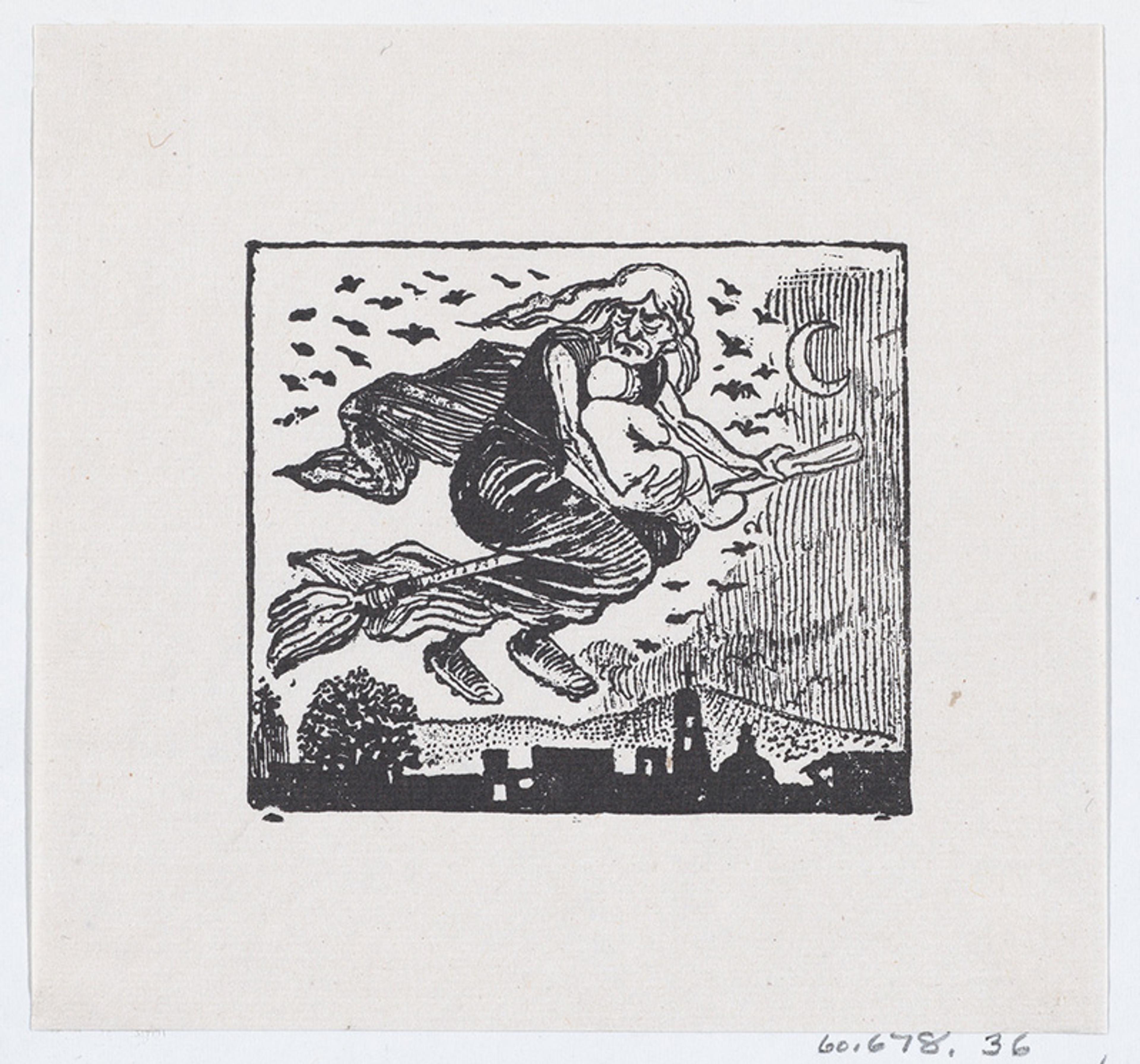

José Guadalupe Posada A witch carrying a child on her broom. C1880-1910. Courtesy the Met Museum New York

Anthropologists, who have studied witchcraft from the early days of their discipline, strive to explain the phenomenon by focusing on social systems. Do accusations of witchcraft reveal social relationships that are ill-defined and likely to give rise to tension? Do they play a role in political or economic rivalry (including among co-wives in polygamous marriages)? Have they been invoked to explain why some people suffer misfortune while others do not?

The inspiration for this approach goes back to the work of E E Evans-Pritchard on the Azande of Central Africa. In his book Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic Among the Azande (1937), E-P (as he was known to students and colleagues) treated accusations and confessions of witchcraft as essential elements of Zande cosmology and a way of maintaining an orderly social life.

Belief in witches was a way of explaining why bad things sometimes happened to good people

Zande witches were said to embody an evil substance with the supernatural power to harm a person whom the witch, consciously or unconsciously, disliked. Unlike witches in many other cultures, the Zande variants attacked by purely mental means. They simply had to harbour ill will against another, and did not, for example, need to recite spells or deliberately send invisible projectiles to injure a person as is common among witches elsewhere.

A group of abinza (witchdoctors) dancing at a seance (do avure), wearing elaborate dance costumes including rattles, headdresses and magical attachments. c1926-7. Photo by E. E. Evans-Pritchard and courtesy the Pitt Rivers Musuem, Oxford

Suffering an illness or other misfortune, especially one that afflicted only themselves and not others (eg, snakebite or another ‘accident’), a Zande man or woman (or their relatives, if the misfortune was fatal) would then suspect the work of a witch who had it in for them; with the help of a diviner, the suspect’s identity could be confirmed. Claiming they were not conscious of causing harm, the accused often confessed. The two parties were then reconciled, and the victim no longer regarded the accused as a witch. In this way, Evans-Pritchard saw belief in witches as a way of explaining why bad things sometimes happened to people, including good people. Since accusations and confessions could reveal strains in relations between people, this was a way to promote and maintain social harmony as well.

A portrait of Bagbeyo, an elder of the Zande people. Bagbeyo was apparently commonly reputed to be a nakuangua or nangbisi (a witch). Photo by E. E. Evans-Pritchard and courtesy the Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford

Later anthropologists followed Evans-Pritchard in interpreting witchcraft as something that served to maintain social systems in a reasonably steady state. This ‘war is peace’ approach found favour despite the social disruption, harm, unhappiness and, sometimes, injury or death of innocents that can follow from openly accusing people of being witches or simply treating them as though they were suspects. What’s more, and in line with a relativist perspective that views human cultures as essentially different from one another, cross-cultural studies came to largely consist of identifying social functions that witchcraft beliefs might perform in particular societies. Identifying someone as a witch might be useful in dissolving or reforming social relationships that are no longer supportable, for example between spouses or co-wives. Or, more generally, belief in witches might be seen as promoting good behaviour, so that people would avoid acting badly towards others for fear of either being accused of witchcraft or having witchcraft used against them.

Because the focus among historians and anthropologists was on single societies, there was little scope for generalisation. And, in any case, it soon became clear that the sorts of people who were accused or suspected of witchcraft varied considerably from group to group. Thus, while globally it is women who are mostly identified as witches, in some societies – including the North American Navaho, and several African societies – most witches are men. In many other places (including Zandeland, according to Evans-Pritchard), men and women are suspected about equally.

Similar variation is found in regard to age, social standing and wealth. Though elderly and impoverished women are suspects in a great variety of places, in some cultures, including the Tlingit and Kaska of Alaska and northwestern Canada and the Bangwa of Cameroon, many of those accused as witches were children. In a witch craze that affected the Kaska during the first two to three decades of the 20th century, dozens of children were put to death in the most horrendous ways, often by members of their own families, thereby depleting the population of this society, which apparently never numbered more than 300 or 400.

The way people make a living also does not determine the occurrence of witchcraft beliefs. Some writers have claimed that witchcraft is absent or rare among small-scale, nomadic or semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer communities with small population densities. But before their integration into modern nation-states, the aforementioned Kaska maintained a belief in witches and anti-witchcraft practices, as did many other native North and South American hunter-gatherers – including the Paiute of eastern Oregon.

Recognising the deficiencies of earlier sociological approaches to witchcraft, my former supervisor at Oxford, Rodney Needham, proposed a better perspective. In his essay Primordial Characters (1978), Needham argued that, to properly understand the witch, we must investigate particular beliefs about witches that find expression in otherwise quite different cultures and different historical settings. Together, these add up to what Needham called ‘the image of the witch’, a complex of ideas, none of which is necessarily connected with particular forms of social organisation.

Needham calls part of the widespread image of the witch the ‘moral component’: representing witches as the absolute opposite of the moral human being. Not surprisingly, under this heading Needham first mentioned cannibalism, but he didn’t say anything else about the remarkably uniform way witches are claimed to prosecute their nefarious deeds. With few exceptions, witches the world over act invisibly; they transform victims or their souls into sacrificial animals, and attack people by piercing or stabbing them with unseen instruments and inserting harmful substances into their bodies. (Piercing is a major technique among the Kalapalo of Brazil, who call witches ‘masters of the darts’, but it also recalls QAnon’s recent claim that Bill Gates, identified as a member of the ‘global elite’, was promoting COVID-19 vaccination with the aim of injecting microchips into unsuspecting recipients.)

European witches plant crosses upside down, perform rituals backwards, dance counterclockwise

Though Needham did not specify it, an equally prominent expression of the moral component of the image is the way witches in most places act to impede normal processes of human life. Most notably, they counteract human procreation by killing both unborn babies in the womb and infants after birth, all while reputedly engaging in disapproved sexual practices that cannot lead to conception. Female witches in Ghana are supposedly able to turn a woman’s uterus upside down so she cannot conceive, while male witches can steal a pregnant woman’s fetus. In some places, including early modern Europe and among the West African Yoruba and the Mapuche Indians of Chile, witches are credited with stealing men’s penises or destroying their semen.

Other traits Needham lists are similarly widespread across cultures. People around the world describe witches as secretly meeting in groups to kill victims, as in the covens of early modern Europe. They are regularly depicted as operating at night, being able to fly (or levitate), associating or identifying with animals, participating in a wide variety of physical and other inversions, and manifesting as nocturnal lights. Though seemingly trivial, this last trait is ubiquitous. Instances are found in all parts of the world, including North and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia and the Pacific islands. Thus, the Sumbanese of eastern Indonesia often call witches ‘those who glow, shine, or flicker (in the night)’. Similarly, in Ghana, the Twi word for practising witchcraft means ‘to glow’.

‘Inversion’, where witches do things in a way opposite to what is proper or normal, is another idea found just about everywhere. European witches were supposed to plant crosses upside down, perform rituals backwards, dance counterclockwise (the inauspicious direction), and do things with the left hand that should be done with the right – just as latter-day satanists have been described as doing. Outside the West, witches are conceived as equally inverted beings. The Nagé people of the Indonesian island of Flores, among whom I conducted fieldwork between 1984 and 2018, describe witches as dancing in the ‘wrong’ direction during their nocturnal cannibalistic feasts. Nagé witches also sleep with their heads pointing the wrong way (towards the sea rather than inland). Similarly, Navaho and Western Apache witches cast harmful spells by reciting ‘good prayers’ backwards; some witches in India are credited with inverted feet; in East Africa witches walk about upside down; Burmese witches sleep on their bellies rather than their backs; ancient Roman writers described witches as capable of reversing the course of rivers – and the list goes on.

Needham argued that the components need not all occur together, and I agree. For example, if Americans recently accused of engaging in satanism are modern examples of witches, so far as I know they have yet to be credited with flying unaided, turning into animals, or walking on their heads. The absence of such attributed abilities, all of which are, of course, physically impossible according to modern physics, is readily explained by the advent of modern scientific education, which has affected the public discourse and presumably the imaginations of even the most uneducated members of Western societies. Yet, what remains in accusations of satanism are ritual homicide, cannibalism, and hindering human reproduction (by reputedly sacrificing children and promoting abortion).

Surviving accusations may thus reflect only what is empirically possible. Even so, they appear central to the image of the witch. For a start, cannibalism, eating fellow humans, is itself a kind of inversion, as well as being in most places an extreme moral outrage. Even in cultures that practise ritual cannibalism (like some in New Guinea), the cannibalism of witches is morally distinguished by its secret, excessive, uncontrolled and indiscriminate aspects. At the same time, modern Western witchcraft, or satanism, has apparently expanded on the witch’s common preference for victimising children by adding paedophilia to their roster of evil deeds. Not entirely original – since sex with children is a charge laid against witches in some traditional African cultures – this addition surely reflects features of modern child-rearing that are quite specific if not unique to the mass societies of the West.

From the arresting series of inversions to manifesting as nocturnal lights to flying unaided, many attributions of witches are encountered so often, in different places and different historical periods, that they cannot credibly be explained as mere coincidences, or something that originated in one culture and simply spread to near and distant others. Some beliefs may have developed independently in different places. But this only begs the question: why should this have occurred? Given the uniformity of the image of the witch worldwide, we can only conclude that it is a product of pan-human psychology.

Needham reached much the same conclusion, but he never took it any further. Drawing on Carl Jung’s concept, he simply characterised the witch as an ‘archetype’, though one that is ‘synthetic’, meaning that it consists of components that need not occur together, and that some people attribute to entities besides witches. As he noted, purely spiritual beings like gods and ghosts can also be inverted, take the form of animals, or be active mainly at night. Yet these commonalities find a ready explanation in a consistent conception of witches as beings with the same supernatural powers as spirits and, simultaneously, flawed humans.

In other words, witches habitually confuse what philosophers recognise as major ontological categories. These comprise essentially different sorts of beings and most notably human beings, nonhuman animals and spirits, which moral humans everywhere keep separate from one another, conceptually and, in some ways, physically as well. People everywhere forbid having sex with animals, while witches are often charged with just that. The Nagé of eastern Indonesia say that such transgressions would turn any individual into a witch.

Curiously, people usually identify social insiders as witches

Admittedly, these observations go only part way to explaining universal witchcraft. If the witch is an inherent tendency of pan-human thought, then its roots must lie deep in human psychology. That said, witchcraft is a complex phenomenon, so certain aspects or components require explanations different from others. Take the series of physical inversions for example. These are products of the universal proclivity to construct metaphors. Being back to front or upside down are particularly concrete, vivid, categorical and psychologically effective ways of representing moral inversion – thinking, feeling and behaving in ways completely opposite to those of ordinary humans, as exemplified by more abstract moral inversions such as sacrificing humans in place of animals, cannibalism, sexual perversion and so on. But calling physical inversions metaphorical is not to suggest they are merely figurative. Another feature of metaphors is that, over time, they can come to be, if not firmly believed, then taken for granted, rarely questioned, and simply accepted as something like fact by the majority of people who habitually use them.

Requiring a different explanatory framework is the foundational belief in the existence of inherently evil human others. Curiously, people usually identify social insiders as witches, at the very least members of the same ethnic group or speaking the same language. Often the accused are also members of the same village or family, and even spouses, parents and siblings. But, in doing so, they represent the suspects as morally alien and inhuman, individuals outside the bounds of humanity and so the exact opposite of ‘people like us’. Therefore, typically high on the list of suspected witches the world over are co-resident slaves (usually descended from war captives), other persons of low rank and, especially when they come from another village (as they often do), wives and their kin.

Linked with the witch’s essential outsiderhood, witchcraft builds on a recognition, unique among humans, of other minds just like our own combined with a countervailing conviction that other people are not exactly like us, and are indeed ‘others’.

One approach traces the hatred and fear to the universal emotional experiences of early childhood. Deriving ultimately from Sigmund Freud, this theory locates witchcraft in an infant’s growing awareness that caregivers exist separately from themselves, and can therefore frustrate as well as satisfy their needs and desires – the first step in a person’s realisation that, to quote Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘hell is other people.’ Because infants find their consequent rage too difficult to bear, the argument goes, they project it onto other people, first the primary caregiver (most likely the mother) and later onto others. The suggestion that the very idea of the witch is rooted in childhood would, in fact, help to explain, via the role that theory assigns to infant caregivers, the global prominence of women among accused witches.

Complementing this approach, cognitive scientists view witchcraft as a product of evolutionary psychology originating among the same Stone Age hunter-gatherers creating emerging religions. A belief in unseen beings is as old as our species, after all, and there’s an enduring psychological attractiveness and memorability to the minimally counterintuitive idea – one that is fantastic yet simple, and not so contrary to common sense that it’s hard to process. If witches are to possess supernatural powers comparable to spirits and engage in practices characteristic of religion, including ritual killing and communal feasting, that only makes sense.

It is no coincidence, either, that contemporary Westerners who accuse others of satanism tend to be evangelical or fundamentalist Protestants, for adherents of these Christian denominations believe in Satan as a being present and active in the world, and in evil as a real power embraced by others who, unlike themselves, are not among God’s elect. According to the evolutionary psychologists, witchcraft belief evolved as a psychological mechanism that aided survival in small-scale Palaeolithic communities by alerting people to the possible existence of internal or external human enemies behaving maliciously in unseen ways.

Like some modern evangelicals, some recent or remaining hunter-gatherers continue to believe there are witches in their midst. These beliefs may no longer serve us, but our species as a whole has survived them – just like we survived the evolution of large brains and heads, the side-effects of which are the life-threatening difficulties women can experience in childbirth. Obviously, isolating the ultimate causes of witchcraft will not immediately solve the social disruption and injustice that accusations (which, in the case of witchcraft, we may assume, are invariably false) can cause. But the more we understand the belief as a tendency inherent in the human condition, the better chance we have of controlling and counteracting its worst effects. At least we’ll have a better idea of what we’re up against.