In April this year, the Meredith Corporation announced that it would reduce Ladies’ Home Journal to a shadow of its former self. The venerable monthly publication, which has catered to middle-class, educated women since its founding in 1883, will now exist only as a website and a quarterly, news-stand-only edition.

This is a big step down from the Journal’s heyday as one of the ‘Seven Sisters’, the magazines that dictated the rules of life for affluent married women throughout the 20th century. The Sisters used to offer a one-stop shop, covering food, health, etiquette, housekeeping, child-rearing, marriage and fashion. They’ve been eclipsed by specialised titles that do what they used to do, but better: Real Simple for housekeeping; Every Day with Rachael Ray for food; Cosmo and Glamour for sex; US Weekly and Star for celebrity gossip. The remaining Sisters – Better Homes and Gardens, Family Circle, Good Housekeeping, Redbook, and Woman’s Day (McCall’s folded in 2002) – now look staid and Middle American in their checkout-line racks.

The Journal and its sisters have struggled to keep up with changing ideas about marriage and motherhood. Nowhere is the herky-jerky evolution of those ideas more visible than in the long history of Ladies’ Home Journal’s trademarked column ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ This feature, one of the Journal’s most popular, has documented and assessed hundreds of troubled unions since its start in 1953. It has operated as a self-conscious standard-bearer for normal marital behaviour, teaching generations of women how they ‘should’ conduct themselves in partnership with men.

For many young women growing up in families that didn’t talk much about marital problems, the Journal’s column was one of the only frank, in-depth discussions of the nuts and bolts of marriage available. Its influence was multi-generational. My mother remembers reading the columns in my grandmother’s 1960s copies of Ladies’ Home Journal. And, throughout the 1980s, as a curious child with small powers of discrimination when it came to reading material, I devoured ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ via my mom’s subscription, sucking up details about affairs, squabbles and separations. From the safety of a pseudonym, its participants’ were willing to air all the family’s dirty laundry. No wonder I loved it.

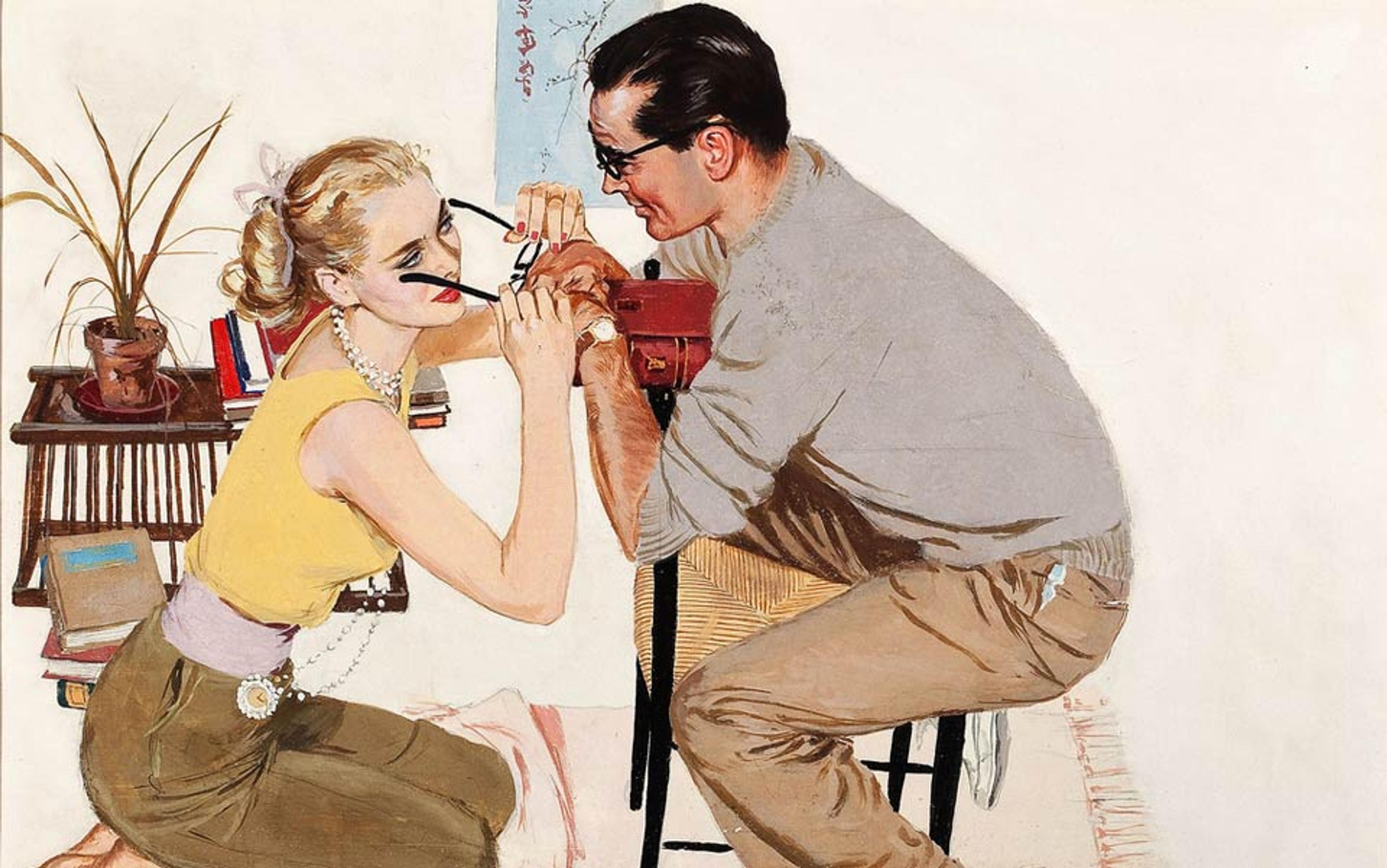

When I heard about the demise of the Journal, I decided to look at the history of ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’. What I found, dipping into the columns published across decades, was the archive of unhappiness that I remembered, full of thrown dishes, turned backs and late-night screaming matches. But I also read a starkly misogynist vision of proper wifeliness that shocked me in its matter-of-factness. We’re used to thinking of the 1950s ‘housewife’ as a vague, happy caricature on gift-shop mugs and postcards – vacuuming in pearls, offering a post-work martini to the returning husband. In its intimate individual details, this advice column resurrects a sharper history, showing the array of cruelties that this kind of marriage could entail, the number of wives who resisted their roles, and the way that mainstream culture tried to put them in their place.

Marriage counselling, once the informal job of clergy, parents and trusted elders, became its own profession in the 1920s. Following increased advocacy for women’s rights, divorce rates in the US rose 15-fold between 1870 and 1920. Meanwhile, psychology and social work found their footing as professions. Some marriage advocates, unable to stem the tide of divorces through legal strictures, turned to counselling as the answer.

‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ owed its DNA to Paul Popenoe and the American Institute for Family Relations (AIFR), which provided real-life cases for the column from its inception through to the mid-1970s. Popenoe had no formal psychological training. A eugenicist, he believed with an evangelical fervour in marriage among people of the ‘better type’ (white, able-bodied, middle-class Americans). The AIFR, which he founded in 1930 in Los Angeles, offered premarital counselling, counselling by mail and personality testing for prospective partners, using inventories such as the Johnson Temperament Analysis, developed by the eugenicist Roswell Johnson in 1941.

the Journal rejected couples Popenoe proposed because of their lower level of education or, in one case, their Jewishness

The AIFR’s project was perfectly suited to serve the booming suburban population of postwar southern California, where many couples had moved, far from their traditional support networks. The conflicts that showed up in the AIFR-generated columns in the Journal reflect the particular problems of their setting: husband is a developer, and works long hours, leaving wife lonely in a suburban neighbourhood; husband decides to relocate to California without consulting wife, and wife is miserably homesick, far from her kin.

These couples ended up in the Journal via a circuitous route. First, the AIFR would submit cases to the Journal for consideration. The magazine would then choose from Popenoe’s suggestions, and a Journal-selected author would shape the case notes and counsellors’ reflections into a coherent whole, granting pseudonyms to the husband and wife. Popenoe and the Journal both favoured couples they considered to be ‘middle-of-the-road’: educated, with good prospects, and presumably white (except in scattered cases where a ‘culture clash’ between Latino and white spouses was the specific problem to be addressed). For Popenoe, the Journal’s column turned into a form of conservative activism, with a very specific ideological vision.

The ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ formula was solid from its first iteration. The headline told the reader the gist of the problem (‘My Husband Isn’t There For Me’; ‘I Had An Affair’). Next came a tripartite narrative. The complainant – until the 1970s, this was always the wife – was introduced. A brief physical description (‘vivacious’; ‘like a Dresden doll’) followed. In the first person, the wife described a specific inciting incident, aired her general grievances, then returned to the past, glossing her childhood, her feelings upon meeting her future husband, their courtship (‘We had so much in common’), and the history of their marriage.

Then the husband, likewise physically described, responded, countering her claims and adding some of his own, while explaining his own family background. The AIFR counsellor had the final word, outlining the concessions and thought revolutions that each partner had to make in order to reconcile. A kicker delivered the ‘happily ever after’ message, and often reported that the couple had contacted the counsellor to share news of the birth of a child. For a modern reader of the column’s 1950s and ’60s archives, it’s hard not to be horrified by the complete and utter awfulness of many of the husbands – both their behaviours, as reported by their wives, and their own responses to counselling. Perhaps more shocking still are the counsellor’s responses. No matter how bad it got, the counsellor always managed to find a way to blame the woman for the couple’s problems.

In March 1957, in the case of ‘Josh’ and ‘Elsa’, Elsa reported that Josh hit her after he came home late from an office party. In the course of her description of their relationship, Elsa tells the counsellor that when their daughter Sally was born: ‘Josh showed plainly his disappointment that the baby wasn’t a boy.’ ‘When the baby and I came home,’ she added, ‘I stayed in bed and let him prepare his own breakfast. He was outraged and yelled so furiously all the neighbours heard him.’ Elsa told the counsellor that she was absolutely miserable in her marriage: ‘When [Josh] abuses me in the presence of our children, when he humiliates me before the neighbours, I want to curl up and die. There is an ache deep in my chest, in my heart. I feel physically sick.’

The counsellor wrote that Elsa was ‘jolted and shocked when I told her she was partly at fault’. This wife needed to be convinced out of her own self-righteous understanding of the situation, the counsellor argued. ‘If she wanted a serene family life, she would have to learn to give Josh what he wanted from their marriage and thereby help him control his temper.’

The Delaware historian Rebecca Davis writes in her book More Perfect Unions (2010) that Popenoe’s beliefs in eugenics led him to ‘build up a deep reserve of distrust for the modern woman’, whom he viewed as responsible for divorces and failures to reproduce. He disapproved of too much education for women; thought ‘frigidity’ ‘resulted from women’s delusions, not their bodies’, and believed that women didn’t understand men, ‘blaming women for mistaking natural sex differences for inconsiderateness’. Popenoe’s place as an arbiter of marital happiness in a mainstream women’s magazine shows that these attitudes, while not universal to his profession, were not wholly anathema to the culture at large.

‘When Alice acknowledged that the language of courtship is seldom the language of marriage, she started keeping household accounts and padlocking her tongue’

The early ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ columns have an unpleasant chiding tone. Popenoe, along with his organisation’s marriage counsellors, thought of female clients as unrealistic babies: immature, and expecting too much glitz from their marriages. There was a strong element of intergenerational critique in their counsel – a sense that young women were seduced by popular culture, and hopelessly unable to ‘keep house’ and make sacrifices. ‘Don’t expect too much romance,’ Popenoe’s counsellors said over and over again.

In treating ‘Ralph’ and ‘Alice’ (February 1953), a young couple who had four children in the space of five years, the counsellor wrote that Alice needed to be convinced to stop ‘nagging’ her husband for affection: ‘Ralph’s way of pronouncing his love was not in extravagant speech but in coming home to her and the children, and displaying his willingness – indeed, his determination – to support them.’ The happy ending was for her to provide: ‘When Alice recognised this fact and acknowledged that the language of courtship and juvenile dreams is seldom the language of marriage, she started keeping household accounts and padlocking her tongue.’

‘Julie’ (December 1961), who had helped her husband ‘Arthur’ build up his business before their children were born and was now an unhappy mother left alone in a big house, missed him and pined for his companionship. Arthur was befuddled, criticising her inability to handle her new role: ‘It seems to be beyond Julie’s talents to drop clothes that require no ironing in a washer-drier combination and then to lift them out and put them away,’ he complained. ‘Sometimes our house resembles the interior of a half-loaded moving van… Julie seems to drift around in a dream.’ The counsellor set Julie straight, asking ‘whether it was logical to expect a driving, ambitious man to devote a large part of his time to entertaining his wife and children’.

Perhaps most disturbingly, ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ counsellors minimised and ignored domestic violence, as in the case of Josh and Elsa. Wives would report incidences of physical aggression, but these were never headlined as the major complaint – they were submerged in the couple’s larger story. Popenoe introduced the September 1953 column, which featured ‘Sue’, a wife who showed up to the counsellor’s office with a ‘large purple bruise darken[ing] her cheekbone’, by referring to the husband’s complaints, rather than the wife’s: ‘Many a husband has to pay the penalty for his wife’s failure to get any real education in homemaking before she married, or to acquire such skills after the wedding, when she must have begun to realise that she needs them.’ (Again: the wife should have known that she wasn’t measuring up.) ‘In a canvas of more the 500 marriages made by the American Institute of Family Relations,’ Popenoe continues, ‘it was interesting to find how bitterly the average man resents a sloppy and slovenly wife – even when his own habits are not beyond criticism.’

In Sue’s case, the counsellor found that her husband ‘Jack’ needed to ‘master his temper’, a simple trick accomplished after ‘a single consultation proved to him that his temper was not “inherited” but represented a poor pattern established in his childhood’. But it was Sue who had the most work to do. She showed a lack of insight – she didn’t understand her husband. By refusing to have sex with him after he hit her, ‘she… touched off another almost inevitable explosion. Many husbands endeavour to make up for their misdeeds by such ardour, a fact of life that wise and loving wives accept.’ Sue had to systematise her housework in order to get good at it – a recommendation that reflected Popenoe’s professional roots in the efficiency-happy 1920s. The happy ending: Sue ‘spends 15 minutes every morning planning and writing down a list of daily tasks. Any specific request of Jack’s takes top position on the list. As she acquits each task, she checks it off the list. This means she finishes one job before she begins another.’

The awfulness of ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ continued throughout the 1960s. Women’s magazines, despite making some grudging concessions to new ideas about womanhood, became a particular target of feminist activists such as Betty Friedan, who quoted liberally from the Seven Sisters in her introduction to The Feminine Mystique (1963). As the historian Jean E Hunter writes in ‘A Daring New Concept: The Ladies’ Home Journal and Modern Feminism’ (1990), the Journal addressed feminism in patchwork bits and pieces, starting in the mid-1960s. It even allowed Friedan to guest edit an issue in June 1964. But the magazine’s editorial stance on feminism vacillated. As Hunter notes, in issues immediately following Friedan’s, articles describing the delight and ‘supreme importance of childrearing’ appeared. Throughout it all, the marriage advice column remained laughably oppressive.

On 18 March 1970, a group of feminist activists occupied the Journal’s offices for 11 hours. They asked that editor-in-chief John Mack Carter, a long-time veteran of women’s magazines who had been at the Journal for five years, resign and allow a woman to lead. The women also objected to the magazine’s content. Quoted in the Village Voice, a participant said: ‘We were there to destroy a publication which feeds off women’s anger and frustration, a magazine which destroys women.’

In a compromise, Carter, who refused to step down, invited the group to edit a special section in the August 1970 edition of the magazine. Carter introduced the section with faint praise: ‘Beneath the shrill accusations and the radical dialectic, our editors heard some convincing truths about the persistence of sexual discrimination in many areas of American life. This new movement,’ he allowed, ‘may have an impact far beyond its extremist eccentricities. It could even triumph over its man-hating bitterness and indeed win humanist gains for all women – and their men.’

Barbara needed to talk to other women in consciousness-raising groups, not to therapists who would convince her that everything was her fault

The edited section, anonymously authored by the group of activists, featured essays on the education of daughters; equal pay for equal work; a birth story; and frank discussion of the role of the clitoris in female orgasms. The activists’ contributions also included a section titled ‘Should This Marriage Be Saved?’

In this column, a woman named ‘Barbara’ told a story that sounded much like many in the standard Journal offering: a husband who wanted more housekeeping work from her; frustrated career ambitions; a generalised sense of unhappiness. ‘If Barbara had told her story to a marriage counsellor,’ the anonymous authors wrote, ‘perhaps to one of the counsellors at the American Institute of Family Relations (which sponsors the ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ column in the Journal), you may be sure the answer would have been yes.’

The authors positioned the women’s liberation movement as a direct alternative to marital counselling, at least of the kind that ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ traditionally offered. Barbara needed to talk to other women in consciousness-raising groups, not to therapists who would convince her that everything was her fault. And most of all, Barbara needed a divorce.

The activists were trying to pull the Journal into line with the evolving field of marriage counselling, which increasingly looked at individual happiness and personal fulfilment in making its prescriptions. But although the Journal began to vary its sources, reducing its exclusive reliance on counsellors from his AIFR, Popenoe – then in the final decade of a very long life – still exerted an influence on the column’s approach.

The prescriptions of Popenoe’s counsellors began to seem more and more out of touch. The effect was exaggerated when the magazine tried to seem relevant to young people’s lives. ‘Allie’ and ‘Kip’, a couple of hippies who appeared in the December 1970 issue, were out of line with each other. Allie had realised she wanted a ‘straight’ life, but didn’t know how to get Kip to give up the world of drugs and ‘free love’. The couple’s problems might be sexy and Aquarian, but the solution was the same as it ever was: Allie had to ‘hold her tongue’ and ‘mend her ways’ to avoid ‘bossing and manipulating’ Kip. Her reward was the shift toward normalcy that she wanted: ‘Now they live in a distant suburb of San Francisco among a new circle of congenial friends who are more concerned with gardening, the Little League and PTA meetings than with the dubious virtues of drugs.’

‘Eric’s tantrums were terrifying. Veins in his neck would bulge and his tongue would become thick with rage as he advanced upon Wendy’

Despite the drag that the increasingly conservative AIFR made on the column, some new methods took hold. In the 1960s and ’70s, counsellors began to meet with both partners at once, assessing their communication styles and coaching their relationship; they tried to improve the couple’s interactions, rather than suss out their individual histories. Group counselling, which became increasingly popular in the 1970s, also appeared in the column’s ‘The Counsellor Responds’ section. In August 1970, the case of ‘Wendy’ and ‘Eric’ – a husband with an anger problem – was ‘resolved’ with the help of group therapy. ‘Eric’s frequent tantrums were terrifying,’ the counsellor reported. ‘Veins in his neck would bulge and his tongue would become thick with rage as he advanced upon [Wendy], screaming vile names and waving his fists.’ The two went to group therapy, ‘where his screaming irrational fits and hostility wore everybody out. “You’re a bastard,” each member of the group accused him in turn.’ Eventually, Eric mended his ways.

By 1978, the column began getting some of its case notes from counsellors who weren’t associated with the AIFR. The difference, in some cases, was a marked one. In June 1982, ‘Gloria’ and ‘Rob’, experiencing marital friction after Rob lost his job and Gloria had to work, received the following advice from Martin Gilbert, a licensed clinical social worker with the Family Counselling Service in Albuquerque. ‘My main function,’ Gilbert wrote, ‘was to help Rob and Gloria see themselves not as stereotypes, but as individuals, and to realise that there was nothing wrong with overlapping roles… Slowly, Rob came to believe that his “gentle strengths” had as much value as those he had always considered “masculine”. With this realisation, he began to feel less threatened by Gloria’s career aspirations and to pitch in more with household chores.’ Gilbert’s was a prescription heavily influenced by the feminism of the decade – and one that Popenoe would have found quite foreign.

The archive of recent ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ columns on the Ladies’ Home Journal website is devoid of the woman-blaming that characterised the rubric’s early decades. Nor is it still acceptable to presume that poor housekeeping is solely a woman’s problem, or that women must endure domestic violence. Of course, there are corners of US culture where being a so-called ‘surrendered wife’ is still a desirable goal. Socially conservative marriage commentators such as the evangelical Christian psychologist James Dobson of Focus on the Family and the US talk radio host Laura Schlessinger, continue to counsel wives to leave their desire for control behind in order to have happier marriages. (In a direct linkage between Popenoe’s ideas and such latter-day conservatives, Dobson spent an early phase of his career at the AIFR.) But these concepts are no longer mainstream in the way they once were.

Even with these advances, there’s a hermetic feeling to the present-day ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ columns, which persist in understanding marital issues as internal to a dyad. Rebecca Davis points out that a historical point of disagreement between marriage counsellors and their clients has been ‘whether shifting economic realities are the cause or the consequence of marital conflict’. Even during the Depression, when some poverty-stricken people attended mandated counselling as part of a range of treatments that included access to financial resources, ‘diagnoses of emotional conflicts rather than economic need annoyed… women and men, who continued to insist on the material origins of their families’ problems’. Later approaches to marriage counselling, influenced by systems theory and object relations theory, would try to see marital problems as part of a network of cultural influence and structural constraint.

Men’s magazines – the closest parallels to the women’s service titles – don’t tend to write about marital troubles, preferring to focus on sex.

There’s none of that larger view in the more recent ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ columns, which see economic trouble as a barrier to be surmounted – as partners. Stretched thin? Price of day-care keeping the wife at home, and she’s missing her job? Husband’s late nights at work translating into disproportionate irritability at small household catastrophes? There’s a sameness in the prescriptions – communicate better! Agree to compromise! – and in the consistently positive outcomes that turn each column into a misleading fairy tale. Surely some of the ‘work’ that needs to be done is social and political, not personal.

Indeed, the column’s very existence in a magazine for educated women sends a powerful message. Men’s magazines – the closest parallels to the women’s service titles – don’t tend to write about marital troubles, preferring to focus on sex. (See the Men’s Health section ‘Sex and Women’; Esquire’s ‘Sex and Dating’.) Even in the fantasy world of mass media, women carry the burden of thinking about relationships.

As a historian and a feminist, I dislike the easy humour we often use to talk about historical misogyny, because I don’t believe it’s dead and gone. The restrictive tone of the 1950s and ’60s-era ‘Can This Marriage Be Saved?’ columns looks like a joke now, to be shelved alongside vintage ads and archived TV shows, occasionally trotted out to prove how far we’ve come. But while the disdainful prescriptiveness of the column’s early years is gone, the implication of its continued presence in the magazine is clear: a healthy marriage is ‘women’s work’. We’re getting somewhere, but we’re not there yet.