I’ve just returned home after a long tour. I’m in a band, one of those travelling circuses of night salesmen, and we ply our shows all over the world. When we’re offered a gig, we usually say yes, as much for the experience as for the money. One day, presumably, people will stop asking. In the meantime, the long months away make the cities and sensory impressions blurry.

Musicians on the road make up a kind of parallel world, criss-crossing each other all over the planet. We tend to eye one another warily in backstage rooms and festival catering tents, like co-workers meeting somewhere unsavoury. Our lives are familiar, and yet we hurry past, too close to our peers for real comfort. Outside this parallel world, I rarely meet people who travel as much as I do, or in quite the same manner: which is to say always and quickly, seeing very little. Who would choose to?

On this last tour, we passed through dozens of cities in Australia and Asia, cities with exotic names that many people can only dream of, and boring ones, too. Plenty of distant places are just as mundane as home, but still their diversity is flattened out by the brutal efficiency of our schedule. We have a single night to get to know a place, and only sometimes the morning, before we hit the road again. I skip through time zones, caught in an impossible pursuit — to be everywhere at once. It’s strange, but travel teaches me more about time than it does about place.

For instance: you can cover a lot of ground in a month’s time. The sheer density of minutes in a day is staggering. You can wake up in Kuala Lumpur and then rest your head 220 miles away in Singapore. You can begin a day travelling by taxi in Indonesia, with a driver who would take you to the Moon for $3, and finish it waiting in the rain for yellow cab at JFK airport, where all the money you have left will hardly get you to Manhattan.

Touring isn’t an extravagance — live shows are how we get by. We’ve been a band for ten years, and never, in the wobbly arc of our career, have record sales come even close to covering our food and rent. I can’t speak for everyone, but this seems about par for the course for those in the middling-celebrity strata of the indie music hierarchy. It’s much worse for the basement bands and the upstarts.

When you’re moving quickly, the only things that appear immobile are the ones moving with you

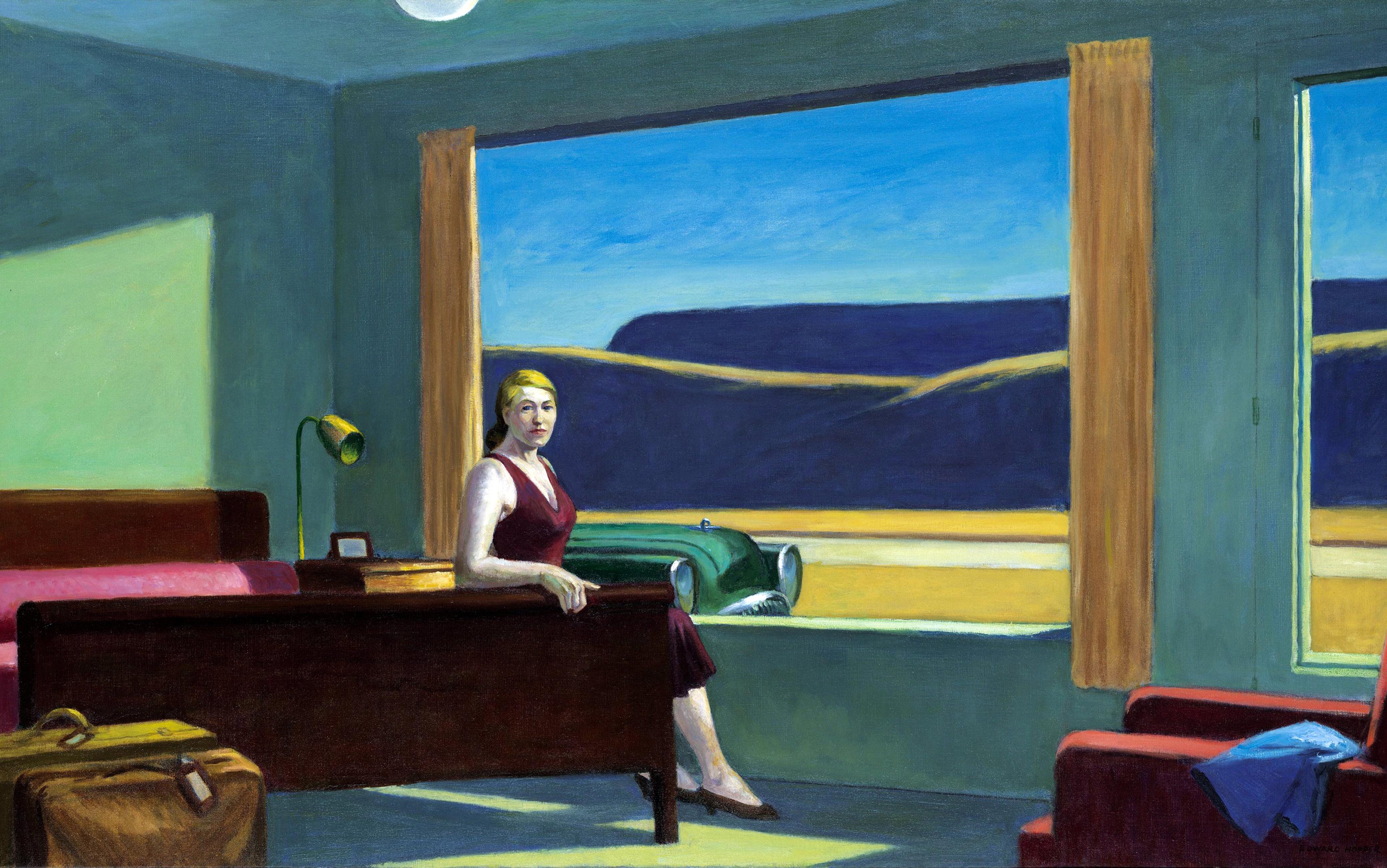

Occasionally, things come along that afford us some wiggle room: maybe a festival paycheck, or a spot on television or in a movie. But mostly it’s the workaday trudge of tour that sustains us. And in the vagaries of a creative life, it’s the tour that feels the most like a job. We clock in, load up, fulfil our contracts, sign paperwork backstage and, hopefully, some records at the merchandise table. We keep receipts, we book flights, we pay taxes. Our nights don’t end with groupies or lines of cocaine. My greatest indulgence is a beer sucked down in front of the TV in a hotel room as I struggle to catch up with the programmes that mark the passage of time in other people’s lives.

When I drift off, I have a recurring dream in which I gaze out the window of a passenger van at a landscape shifting too quickly to discern. All I see is mist, a space eaten by time. When you’re moving quickly, the only things that appear immobile are the ones moving with you: that’s basic relativity. It’s as though you’re standing still, or at best slowly tugging a suitcase, while the world spins around you. I focus with manic intensity on my personal effects: my phone, my jacket, the nylon sleeve that holds my passport.

Bands on tour will often refer to their van as their home. They’re not exaggerating. It’s one way to keep sane as time zones shift around your body, and languages, too. Any constant can become a kind of home, even the music itself. My technique is to buy things everywhere I go, not as souvenirs but because I’m trying to weigh myself down on to the world. My suitcase is an albatross of Scandinavian toothpastes and Japanese notebooks. Perhaps these purchases will help me to remember something other than a blurry view from a car window, even if it is just the memory of the moment I bought them.

It’s hard to look beyond my artificial bubbles of stillness, and even harder to imagine that, as I write this, chugging caffeine at home in California, the ferry still shuttles across Kowloon Bay, crossing wakes with the last remaining junk boats in Hong Kong harbour. Or that those temple macaques in Bali still sell each other out for a chance at some peanuts. That the curries still simmer, money still continues to change hands, and all the worshippers still pray to their gods. How can it all go on even when I’m not there looking at it? This thought has struck me, like a spasm, many times, especially in large cities. I find it paralysing and magnificent in equal measure.

I felt nothing, except for self-consciousness and the impulse to snap a dozen pictures I haven’t looked at since

In touring the world I’ve only ever sliced person-sized cross-sections through a massive simultaneity of experience. Like cuts in flesh, they heal up behind me, save for a few scars here and there where I might have managed to make contact, or where I ended up in the background of someone else’s holiday snapshot. On some scale, this is true for everyone. ‘What is life,’ wrote George Satayana in his essay ‘The Philosophy of Travel’ (1964), ‘but a form of motion and a journey through a foreign world?’

Friends often ask which were my favourite places to visit, but the truth is I can’t hold them all in my mind. What makes a place nice to visit, anyway? The pleasure it provides for its visitors? Who am I that Thailand must delight me? I’m horrified when a country is described as having a ‘warm people’, as though each citizen must please the sweaty strangers who choke the streets. Thailand — or any other place — can only exist. And by existing can only remind the traveller that other modalities are possible, that no way of living is a natural consequence of being alive on this planet. That should be enough.

Travel is inherently narcissistic. Even if we’re looking to be knocked off our axis, we’re still in the business of self-improvement. People want to go to faraway places and return changed. A lot rides on this expectation. We hunt for perspective, for miraculous connections, but when these moments happen, we don’t always recognise them — or we look in the wrong places. There is a collection of jungle villages around Ubud on the Indonesian island of Bali, which is as remote and humid and disorienting as any foreign place. The landscape is clogged with temples spewing incense, and yet long lines of Western tourists snake out the doorway of the single mountain temple that featured in Elizabeth Gilbert’s book Eat, Pray, Love (2006). It’s easy to laugh at these people. It’s easy to say that they are missing the point, but are they? Maybe they’re just mainlining into the essence of what travel is always already about: pat revelations about the self. When we were in Bali, we went to a different temple, and our dirty tennis shoes looked ridiculous beneath the stiff embroidered sarongs we were commanded to wear. I felt nothing, except for self-consciousness and the impulse to snap a dozen pictures I haven’t looked at since.

The strangest dissonance of this life is the uneasy balance we strike between chaos and routine. During our shows, we throw the force of our energy into manifesting an unbridled, spirited experience for the audience. They expect this, every night. They’ve paid good money, and, like any travellers, hope to return home with a story. It’s not quite the mountain temple, but to the ecosystem of acolytes that emerge at our shows, the band is a vehicle for enlightenment, or, at the very least, experience.

To admit that we perform in other cities violates the terms of an unspoken covenant, in which we exist solely for them, and they for us

The concert is a finite moment in time. It has intent. The band is summoned to the proscenium; any implication of our grubby tour van, any residue from last night’s show, any evidence of our existence outside the stage is erased by the sheer collective will of the crowd. We are rendered placeless, timeless, without context.

It’s taken me 10 years on the road to realise this. Just as it boggles me to imagine that the places I’ve visited continue to exist in my absence, the audiences we play for firmly believe that we are ephemeral. To admit that we perform in other cities, night after night, violates the terms of an unspoken covenant in which we exist solely for them and they for us. But we must keep moving, and so must they, countless trajectories of human life careening outwards from the moment the lights go down. A concert, in this sense, isn’t kinetic: it’s stillness itself, a world briefly paused.

One of my fondest tour memories is going to the movies in North Platte, Nebraska. After weeks of beer-stale rock clubs, only such an everyday pleasure can reset your barometer to normal. Suddenly, everything can become magic again. At the end of the night, the cashier — a small-town misfit, not unlike those I’ve met in countless venues from Riga to Xi’an — gave us a garbage bag filled with the theatre’s leftover popcorn. He didn’t know us; he just knew we weren’t from North Platte, and that was enough for him. The popcorn was stale and cold and buttery, and the town was closed for the night. We lugged the bag, nearly the size of a person, to a moonlit field out back. Like teenagers, we tossed it at one another in great handfuls under the wide, feathery sky, before emptying the whole bag on the grass for the birds to eat. The next morning it was gone, and so were we.