Who were the Neanderthals? Even for archaeologists working at the trowel’s edge of contemporary science, it can be hard to see Neanderthals as anything more than intriguing abstractions, mixed up with the likes of mammoths, woolly rhinos and sabre-toothed cats. But they were certainly here: squinting against sunrises, sucking lungfuls of air, leaving footprints behind in the mud, sand and snow. Crouching to dig in a cave or rock-shelter, I’ve often wondered what it would be like to watch history rewind, and see the empty spaces leap with shifting, living shadows: to collapse time, reach out, and allow my skin to graze the warmth of a Neanderthal body, squatting right there beside me.

The business of archaeology is about summoning wraiths from the graveyards of millennia, after the vagaries of decay and erosion have done their work. Everything begins as fragments. Yet in recent years, poring over these shards has produced a revolution in our understanding of Neanderthals. Contrary to what we once thought, they were far from brutish, ‘lesser’ beings, or mere evolutionary losers on a withered branch of our family tree. Rather, the invention of new dating techniques, analysis of thousands more fossils and artefacts, and advances in ancient DNA research have collectively revealed the extent to which the lives of Neanderthals are braided together with our own.

When Western science first encountered the Neanderthals in 1856, they were a jumble of bones – one of which was a broken skull dome. Blasted out of the rock by a pair of Italian miners in the Kleine Feldhofer cave in Germany’s Neander Valley (‘Neandertal’), enough remained of the weirdly flat skull with colossal brow ridges to hint at something alien yet human-like. The upper face bespoke a prodigious nose between cavernous eye sockets; there were also limb bones, bulkier than any known human’s. From the beginning, Neanderthals, dubbed Homo neanderthalensis, were tantalising in their incompleteness.

Shortly after, an entire skull emerged at the other end of Europe: in Gibraltar (on British soil, no less, to the delight of the London intelligentsia). The Forbes’ Quarry skull had actually been found some years earlier, in 1848, but had gone mostly unremarked in a museum collection. The bone itself was hidden by a coating of hardened sediment, and its nature obscured by the fact that nobody was primed to ‘see’ extinct hominins (the group of primates that includes humans, our immediate ancestors and other vanished human species). But in December 1863, Thomas Hodgkin, a visiting physician with experience in ethnography and anatomy, recognised the skull’s significance. He suggested it be sent to his friend George Busk, who had translated the analysis of the Feldhofer bones from German. When the skull arrived in London in July 1864, it removed any uncertainty about the Neanderthals’ link to us: lacking a primitive ape-like muzzle, these apparitions from an unknown aeon were decidedly and disturbingly human-like.

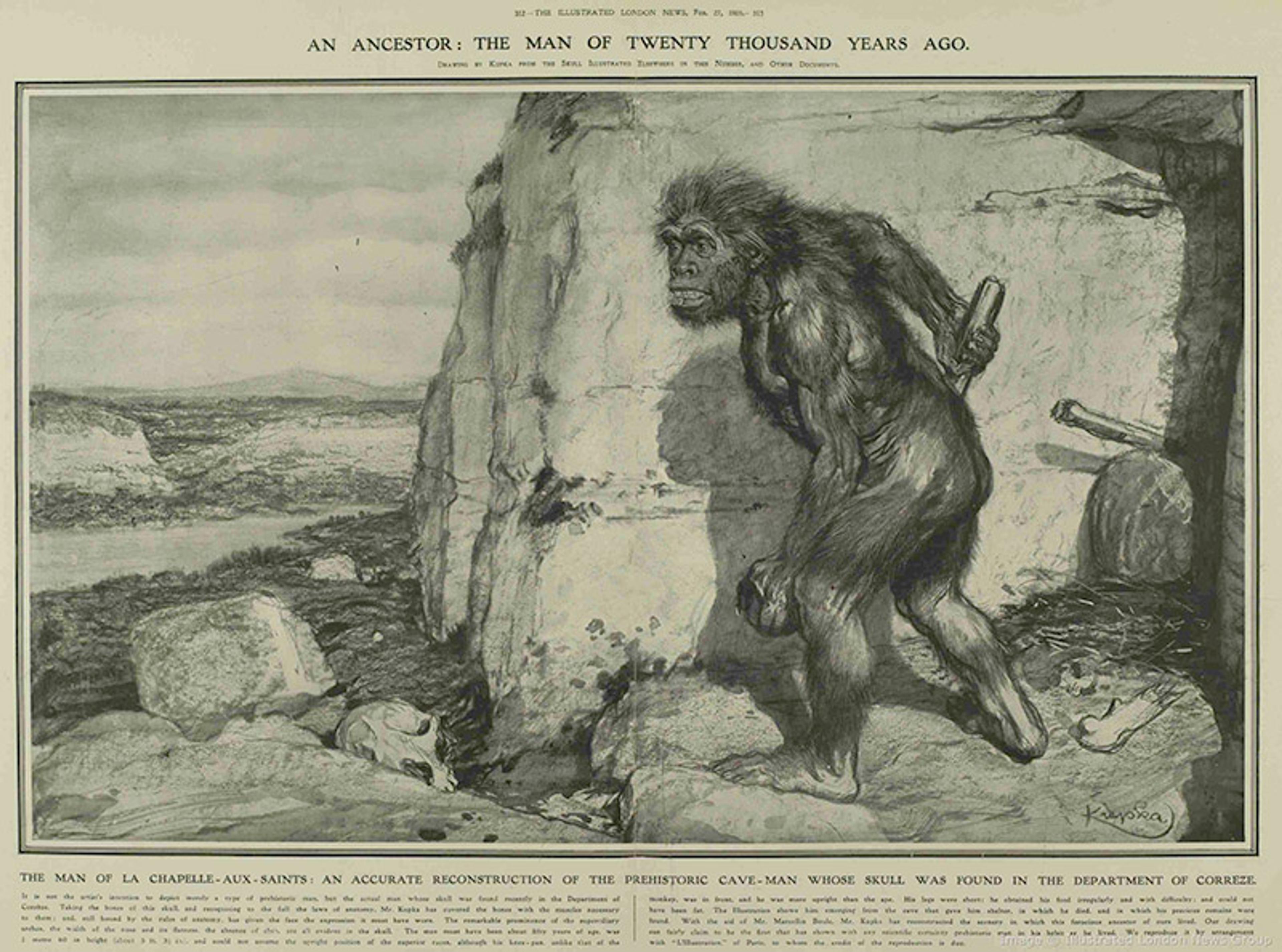

In the wake of this first flurry of discoveries, further Neanderthal specimens sprang up across Europe – until in 1908, a nearly complete skeleton of an adult male was disinterred from the La Chapelle-aux-Saints cave in France. The publication of the find included illustrations made with cutting-edge Edwardian technology, in the form of 3D ‘stereo’ photographs. Reconstructions of the ‘Old Man’ of La Chapelle varied widely from hairy ‘ape man’ to a tidy-bearded – albeit shirtless – member of the bourgeoisie. But anatomically, at least, it was no longer possible to argue that he and his kind were closer to nonhuman animals than to living people. Now scholars began asking the deeper question: so Neanderthals looked the part, but were they truly ‘people’, like us?

Societies have long obsessed about what separates humans from nature. The question goes far deeper than surface appearances. The reality of the Neanderthals – predicted nowhere in religious texts or the science of the day – represented a profound culture shock to the mid-Victorian worldview. The rise of geology and palaeontology, and Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace’s presentation of the evidence for natural selection in 1858, amplified the shock. There was no way the world was just a few thousand years old, or that humans were fashioned wholesale from on-high. If Genesis could not be trusted, then what could?

Scientific discoveries never occur in a social vacuum. The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus formalised the ladder of life in 1758, when he crowned white European males as the ‘type specimen’ of our species. At a stroke of his pen, everyone else on the planet was demoted to a nonstandard, inferior version of humanity – identified by supposedly less advanced physiques, character and culture. In such a world, it was logical that the skull and bones from the Neander Valley were immediately compared with ethnic groups branded the most ‘brutal’ by their colonisers.

In 1863, the English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley claimed a striking similarity between Neanderthal brow ridges and the ‘lowering, threatening expression’ he perceived in the skulls of Aboriginal peoples – ignoring the clear difference in anatomical shape. The European intellectual elite were mostly blind to the possibility that Neanderthals were evidence of a common heritage for living people. Instead, they saw ‘scientific’ proof of the racist hierarchies that positioned non-Europeans as less evolved – although remaining puzzled that ‘savages’ nevertheless appeared to possess brains as big as those filling their own top hats. Up until the 1960s, scientists were still publishing theories of human evolution proposing that different races had budded off the human family tree sooner than others, with Caucasians the most recent arrivals, and therefore the least ‘primitive’.

It’s now clear that Neanderthals weren’t any less ‘evolved’ than us

These ideas have cast a long shadow over the study of Neanderthals. While the science has advanced dramatically in the past decade, popular perceptions and media coverage are still catching up. The big picture now points to early hominins evolving in Africa before dispersing outward in waves. In Europe, Neanderthals appeared in fossil records as a distinct population more than 400,000 years ago, and went on to occupy a vast swathe of Eurasia. Then they vanished 42,000-40,000 years ago. This period also witnessed the appearance in Europe of another hominin species: us, Homo sapiens.

For decades, most of the scientific community believed this conjunction implied causation. It was assumed that humans replaced Neanderthals without interbreeding – the implication being that Neanderthals could not compete with our ‘superior’ capacities. Influential theories typecast them as creatures who were intrinsically antisocial, even to their own kind. Palaeoanthropologists believed that Neanderthals’ social networks resembled chimpanzees’, in which members tend to treat ‘out-group’ counterparts as enemies to be driven away or eliminated, not fellows with whom to communicate or interact. This inference stemmed from the fact that Neanderthals generally moved their tools short distances from the source of the stone to the site where they were discovered – brushing aside the rare but widespread presence of artefact transfers over 100 km.

However, it’s now clear that Neanderthals weren’t any less ‘evolved’ than us. Nor is there much decisive evidence that they were fundamentally less social or less inclined to mingle with those outside their tribe. They simply travelled on their own path, running roughly in parallel to ours, albeit with different twists and turns in the trail. They were not parochial cul-de-sac Europeans, but instead lived across immensely varied lands well into Asia – even towards the shores of the Pacific, if some Chinese stone tools are any indicator. They were capable hunters and knowledgeable gatherers; artisan crafters across a range of materials. Weathering multiple glacial cycles, they survived extreme climate change as rapid and severe as the worst predictions for the coming centuries.

Exploring who the Neanderthals really were is complex, not least because each facet of their lives was interconnected. Finding out what they ate – in some cases, based on the microscopic remains of food found cemented between their teeth – can shed light on where they went, how often they moved around, and whether they planned ahead. At first, researchers assumed that Neanderthals were hunters; one of the very earliest reconstruction drawings included a spear, and by the late-19th century archaeologists were looking out for traces of butchered animal remains. Yet because many more sites were preserved from glacial periods than warm climates, scientists concluded that Neanderthals must have lived predominantly in harsh environments, where they barely clung on.

By the 1960s, it was widely believed that Neanderthals were primarily carnivores who dwelt in frigid surroundings with very little vegetation. This was in part based on ignorance of Indigenous plant use in comparable habitats, but also because anthropology was male-dominated, and particularly focused on the lives of big-game hunters. Reactions against this perspective, however – including from feminist scholars – pointed out that a significant proportion of calories came from the ‘slow and steady’ second part of the hunter-gatherer equation: not only plants, but small-game hunting and fishing. In reality, people who live by foraging are deeply embedded in their environment, and everyone, including women, elders and young children, takes part.

These shifts in perspective brought plants and creatures such as birds back into the picture, but their evidence among Neanderthals remained elusive in the archaeological record. The nadir came during the 1980s, when scholars proposed that the vast amounts of bones and teeth in Neanderthal sites weren’t even from hunting, but scavenging. This left Neanderthals skulking around the fringes of hyena or lion kills, grabbing scant scraps without invoking the ire of ‘true’ predators.

However, this scenario was also overturned as archaeology began to mature as a discipline throughout the final decades of the 20th century. A new array of methods, and a growing awareness of bias due to outdated excavation and collection standards, brought our perception of Neanderthals into much sharper resolution. In the decades since, evidence from hundreds of sites has been meticulously parsed and amassed, revealing the Neanderthals as top-level team hunters. They took on mighty beasts including bears, rhinos and possibly mammoth, using finely honed wooden spears for close-quarters jabbing; others were likely thrown like javelins. The myth of speedy critters such as birds or rabbits being out of reach has been crushed, while seafood was at least sometimes on the menu. Strand-line gathering was practised, whether for shellfish or the odd washed-up marine mammal, and maybe freshwater fish.

Plants supplemented this varied carnivorous diet. Neanderthals made their living across a huge geographical area, from North Wales down to Palestine, and eastwards nearly halfway across Siberia, so it’s no wonder we find preserved morsels of figs, olives, pistachios and date palm in caves across the Mediterranean and West Asia. In archaeological sediments and on stone tools, remnants of tubers (wild radish, water lily) and seeds (wild cereal, peas and lentils) have also been discovered. All this tells us that Neanderthals were very likely chowing down on cooked food more diverse than meat. Perhaps food was as important to social identity tens of millennia ago as it is for us today.

What if the first Homo sapiens walked into dark caves to find walls blazing with ancient visions?

Aside from the visceral satisfaction of a full belly, did the Neanderthals experience passions at a more profound level? Were they capable of self-expression, and abstract thought? Archaeologists are nudging closer to affirmative answers. Paintings found at three caves in Spain – La Pasiega, Maltravieso and Ardales – include red-daubed stalactites and flowstone, a clean vertical line and, most enchanting of all, a stencilled silhouette of a hand. Just recently, scientists applied a dating technique measuring the radioactive decay of uranium-thorium in the minerals encrusting the paintings, thereby revealing a minimum age. The results were startling: the oldest ranged from 67,000-52,000 years, appearing some 20,000-7,000 years before we believe that H sapiens arrived in Europe. For many scholars, this represents strong evidence that Neanderthals were responsible. (Others are more hesitant: dating millimetre-thick flowstone layers is complex, and some results suggested contamination.)

Cave art at La Pasiega in Spain, dated by researchers at the University of Southampton to between 67,000 and 52,000 years old. Photo by P Saura

Studies across Europe had already found that many cave paintings rested on a substratum of red hand-stencils, lines and dots. The line image at the La Pasiega site seems connected to a ladder-like form, although the other parts might have been added later. Even so, the findings raise the possibility that the first H sapiens entering Europe’s caves walked into the darkness to find, not blank canvases, but walls blazing with ancient visions. If genuine, these discoveries have exposed a hidden layer of Neanderthal self-expression, sitting beneath the more famous Upper Palaeolithic oeuvre. Perhaps painting was even something our species actually learned, rather than being the independent wellspring of art.

Some of the Neanderthals’ creations carry more than a hint of the eldritch – structures so old that their attribution is unquestionable. In the 1990s, hundreds of metres deep inside the Bruniquel cave in southern France, researchers uncovered stalagmites snapped off and arranged into two rings, encircling smaller piles. But it was only in 2013, after a suspiciously old radiocarbon measurement was taken, that researchers began studying them in detail. Over 174,000 years ago, it seems that Neanderthals walked into the isolated chamber and carefully built these large circular structures. More than 400 pieces from the central parts of the stalagmite columns were placed in layers, some balanced on top of each other, others standing in parallel. Many had been extensively burned, and blazes had been kindled in the small piles. At least some of the fuel was bone, potentially including bear, which isn’t easy to set and keep alight. So far there are no artifacts, and no explanation for the rings, but these structures would have taken time and planning to create, and the foresight to provide sufficient illumination underground. Research is ongoing – most excitingly, to see what lies beneath the floor, entombed in calcium carbonate – but Bruniquel has already opened a vista onto a Neanderthal mind as elaborate as our own.

It’s important to add a note of caution to all this, since Palaeolithic archaeology is still full of ‘unknown unknowns’. It’s true that we have no fossil evidence for H sapiens west of the Danube delta – never mind southern Iberia – before 45,000 years ago, which leaves Neanderthals as the chief suspects for the paintings. But absence of bones does not prove absence of hominins, and we know that H sapiens were making their way into the Levant by at least 150,000 years ago. So the case is not entirely closed for the cave art, even if the 3D creation at Bruniquel seems secure. Still, these revelations have radically altered our understanding, and expectations, of what Neanderthals did in their daily lives – which now includes the possibility of more esoteric practices.

Alongside the archaeological evidence, genetics is the second pillar of the recent scientific reappraisal of the Neanderthals. Increasingly refined data suggest that humans and Neanderthals shared an ancestor around 800,000-700,000 years ago, before they split along different evolutionary paths. This process could even have taken place within genetically diverse but interconnected hominin populations that evolved in Africa, and moved out from there to the Near East and farther lands.

In 2010, researchers analysed the genome of three Neanderthal individuals, and compared the data with modern humans from various parts of the world. Based on genetic links, it seems that some time after 200,000 years ago, early H sapiens emerging from Africa interbred with Eurasia’s indigenous hominin inhabitants. That’s why the genomes of all living people – with the exception of those from sub-Saharan Africa – contain a small percentage of Neanderthal DNA. However it happened, the science is clear: to produce the amount of DNA surviving today, taking into account complex processes of selection against Neanderthal genes and less fertile hybrids, there must have been an awful lot of sex between the communities.

This finding rocked the scientific world, and shredded the ‘replacement without interbreeding’ story of the Neanderthals’ decline. Living people preserve a stunning 20 per cent, maybe more, of the Neanderthal genome, albeit as a somewhat tattered archive that’s distributed between different populations. Even more surprisingly, it’s not Western Europeans who have the most Neanderthal DNA: East Asians have up to a fifth more. There were also numerous phases of hybridisation. The earliest known encounter happened more than 220,000 years ago, when a female ancestor of H sapiens mated with a male Neanderthal – much earlier than other known interbreeding between the two groups. At the other end of the temporal scale, the jaw of a human who lived 40,000 years ago in Romania reveals that he counted a Neanderthal among his ancestors just four to six generations back – right at the time when they were about to disappear from the fossil record.

The girl was a first-generation hybrid: her mother Neanderthal, her father Denisovan

In the same year as the Neanderthal DNA announcement, humans were introduced to another long-lost cousin we didn’t even know we had – and with whom we’d also merged. Since the 1970s, Russian scientists had been excavating the Denisova cave in western Siberia. Among thousands of bones they’d found was the tip of a child’s pinky finger. Genetic analysis published in 2010 revealed it to be an entirely unknown hominin population. The ‘Denisovans’, as they were called, were a ‘sister’ group to the Neanderthals, branching off around 600,000-430,000 years ago. A sizeable proportion of the Denisovan genome survives in us, and scientists have pieced together evidence that we interbred with them multiple times. Many more Denisovans have now been identified at the same site, from tiny scraps of bone or even DNA in the cave sediment itself. Yet we still have no idea what these people really looked like, beyond the fact some had dark eyes and skin.

In yet another twist, it turns out the Neanderthals and Denisovans were close contemporaries, living in the same region for thousands of years. During protein sampling aimed at locating more hominins among unidentified bones from the cave, one stood out. Researchers had chanced upon a bone fragment from a girl, probably a teenager, who was a first-generation hybrid: her mother a Neanderthal, her father a Denisovan. Even more incredibly, her paternal ancestry revealed an even older genetic record of mixing between these populations, hundreds of generations before.

It’s hard to square these narratives of repeated contact and reproduction with the archaeological record of the Neanderthals’ sudden demise. Everything we’ve found, whether from new excavations or improved dating, has drawn the noose tighter around that period of time around 40,000 years ago, when Neanderthals’ distinctive skeletal and material remains disappear. Given the chronological resolution that’s possible so far back, this is tantamount to an almost simultaneous vanishing across their entire geographical range. Yet the genetics shows that they were not extinguished, but rather engulfed in a human flood. H sapiens weren’t their executioners so much as their assimilators.

It’s not clear how or why the encounters that led to interbreeding took place. For starters, we shouldn’t treat Neanderthals or early H sapiens as monolithic entities; in reality, the population dynamics must have been enormously varied, with groups spreading out and mingling in different ways in different places. What about the result of all these trysts: with whom, and how, were the hundreds, if not thousands, of hybrid babies raised? Basic anatomy, combined with neurocognitive and psychological research, both imply that these youngsters needed care, support and love to survive and flourish – just as our own offspring do. But does this mean that entire groups merged physically and culturally, or that our mixed genetic dossier is the byproduct of a profusion of ‘one-offs’, accidental encounters that accumulated over 100,000 years? At present we can make only hazy guesses.

Beyond the advances in science, these changes in perspective on Neanderthals are the fruit of a longstanding cultural obsession. Since 1856, we have been trying to capture the likeness of these people – and yes, Neanderthals must indeed be seen as people, albeit of another kind. Yet the portrait is never finished. With each new archaeological advance, they edge closer and closer to us, feeding our hunger to know ever-more intimate details. Yet something lurks: niggling, uncanny. Evolution has primed us with extraordinarily sensitive face-detection capabilities, but this comes with a deep-brain warning system. When faces are not obviously fake, but fall short of hyper-realistic, they snag our reflex recognition while also triggering alarm.

This disquieting aversion to aberrance, the so-called ‘uncanny valley’ effect, was observed in people’s reactions to robots as far back as the 1970s. One explanation for the ‘dyspathy’ it evokes is a protective instinct, helping us recognise threats from cadavers or the diseased. The Neanderthals induce something similar, a mirror image of us in so many ways, yet somehow aslant. Their liminal quality, at some anthropic edge, produces an uneasy tension. We mentally flinch at the same time as being drawn towards them, because they force us to reconsider how we mark the borders of humanity.

This is why the hand stencil at Maltravieso is so breathtaking. It’s a manifestation of corporeality, proof that all those untouchable skeletons in museum cases were once real, vital bodies. Until that point, the rare cases of Neanderthal ‘trace fossils’ were little more than blurred outlines, mostly footprints at just a few sites. A single, clear fingerprint was found around 50 years ago during industrial open-cast mining in the foothills of the Harz Mountains in Germany. It was imprinted on the surface of a piece of soft birch tar. Cooked from bark, this is the world’s first synthetic material, a natural glue used to join stone tip to wooden handle. The Neanderthal who sat fashioning the tool 80,000 years ago, wreathed in astringent fumes, was probably thinking about the near future – how much longer the stone edge would last, when the season would shift – little knowing these actions would stretch to a world thousands of generations later, as a single finger pressed a whorl into the softened tar.

Corporeal encounters with the Neanderthals can bewitch us because they perform a sort of temporal sorcery. Hands pressed on cave walls seem to imbue the rock with the memory of warmth; bodies moving against each other 50,000 years ago become time-travellers in the blood of their descendants. The changing visions we have conjured in our imaginations are made manifest in how Neanderthals are represented in artistic recreations – from the strikingly bestial and depressed-looking creatures of the Victorian era, to the exquisite digital portraits of the contemporary artist Tom Björklund, whose Neanderthals certainly think, feel and dream as much as we do.

There is no cognitive chasm between us, just as there was no reproductive barrier

Today, the story of the Neanderthals is still in flux. It is only 10 years since the watershed DNA discovery and subsequent demolition of their status as evolutionary dead-losses. We now know there were no Neanderthal endlings, no last lonely survivors. Many researchers now question whether we can even think of them as a different species. All the new evidence calls into question the way we have theorised their lives, often involving lists of standards they must meet to be considered genuinely human. ‘Modern’ behaviour has always been a very particular version of how we like to think of ourselves. A classic example – still being played out in arguments over re-excavation of the La Chapelle site – is at what point are we prepared to grant Neanderthals a conception of death? Too often, clear evidence for special treatment of the deceased is not enough; only a perfectly cut grave, the epitome of ‘proper’ Christian burial, is considered proof of meaningful social practices.

The next step is to kick our habit of narcissism and self-projection, and try to illuminate the Neanderthals on their own terms. We must do more than swing between a fetish and fear of exoticism versus a naive belief that they were ‘just like us’. Taking the archaeology at face value, and according the same standards of proof we permit for early H sapiens, shows that there is no cognitive chasm between us, just as there was no reproductive barrier. The fascination should lie in the variety of Neanderthals’ ways of life, and what they reveal not only about our deep connection, but also about the parallel stories of hominins on Earth.

Our confusion about Neanderthals and their place in our prehistory mirrors certain debates in astronomy – another discipline that deals in difficult-to-imagine spans of time and space. Pluto, our Solar System’s outsider, had long been classed as a planet, if a rather remote and disappointing one. But new observational technologies have allowed us to see that the Kuiper belt, the zone at the edge of the solar system where interstellar space begins, isn’t Pluto’s lonely empire; instead, it is speckled with a vast population of other astronomical bodies. When Pluto was consequently reclassified as a ‘dwarf planet’, the research refocused attention on more interesting and nuanced questions than its contested planetary status. What were these other Kuiper belt worlds like, and where did they come from? How did they relate to Pluto, and more pressingly, what could we do to learn more about them?

Human origins research in the past decade has discovered its own Kuiper belt of mysterious hominins. Some, like the Denisovans, are just now coming into view, while others probably lurk undetected. But no matter how large the family becomes, as our first-found relations, the Neanderthals will feel closest: a foil for what we were, are and might yet be. Yet their relatedness to us is hardly the most interesting thing about them. Instead of a cautionary tale of a disreputable cousin, they are a uniquely precious mirror that refracts, rather than reflects. Far from some primitive offshoot, Neanderthals should be more accurately understood as another of nature’s experiments in humanity.