Touch is the first sense by which we encounter the world, and the final one to leave us as we approach death’s edge. ‘Touch comes before sight, before speech,’ writes Margaret Atwood in her novel The Blind Assassin (2000). ‘It is the first language and the last, and it always tells the truth.’ Our biology bears this out. Human foetuses are covered in fine hairs known as lanugo, which appear around 16 weeks of pregnancy. Some researchers believe that these delicate filaments enhance the pleasant sensations of our mother’s amniotic fluid gently washing over our skin, a precursor to the warm and calming feeling that a child, once born, will derive from being hugged.

Touch has always been my favourite sense – a loyal friend, something I can rely on to lift me up when I’m feeling down, or spread joy when I’m on a high. As an Italian living abroad for more than a decade, I often suffered from a kind of touch hunger, which had knock-on consequences for my mood and health more generally. People in northern Europe use social touch much less than people in southern Europe. In hindsight, it’s not surprising that I spent the past few years studying touch as a scientist.

Lately, though, touch has been going through a ‘prohibition era’: it’s been a rough time for this most important of the senses. The 2020 pandemic served to make touch the ultimate taboo, next to coughing and sneezing in public. While people suffering from COVID-19 can lose the sense of smell and taste, touch is the sense that has been diminished for almost all of us, test-positive or not, symptomatic or not, hospitalised or not. Touch is the sense that has paid the highest price.

But if physical distance is what protects us, it’s also what stands in the way of care and nurturance. Looking after another human being almost inevitably involves touching them – from the very basic needs of bathing, dressing, lifting, assisting and medical treatment (usually referred to as instrumental touch), to the more affective tactile exchanges that aim to communicate, provide comfort and offer support (defined as expressive touch). Research in osteopathy and manual therapy, where practitioners have been working closely with neuroscientists on affective touch, suggests that the beneficial effect of massage therapy goes well beyond the actual manoeuvre performed by the therapist. Rather, there is something special simply in the act of resting one’s hands on the skin of the client. There is no care, there is no cure, without touch.

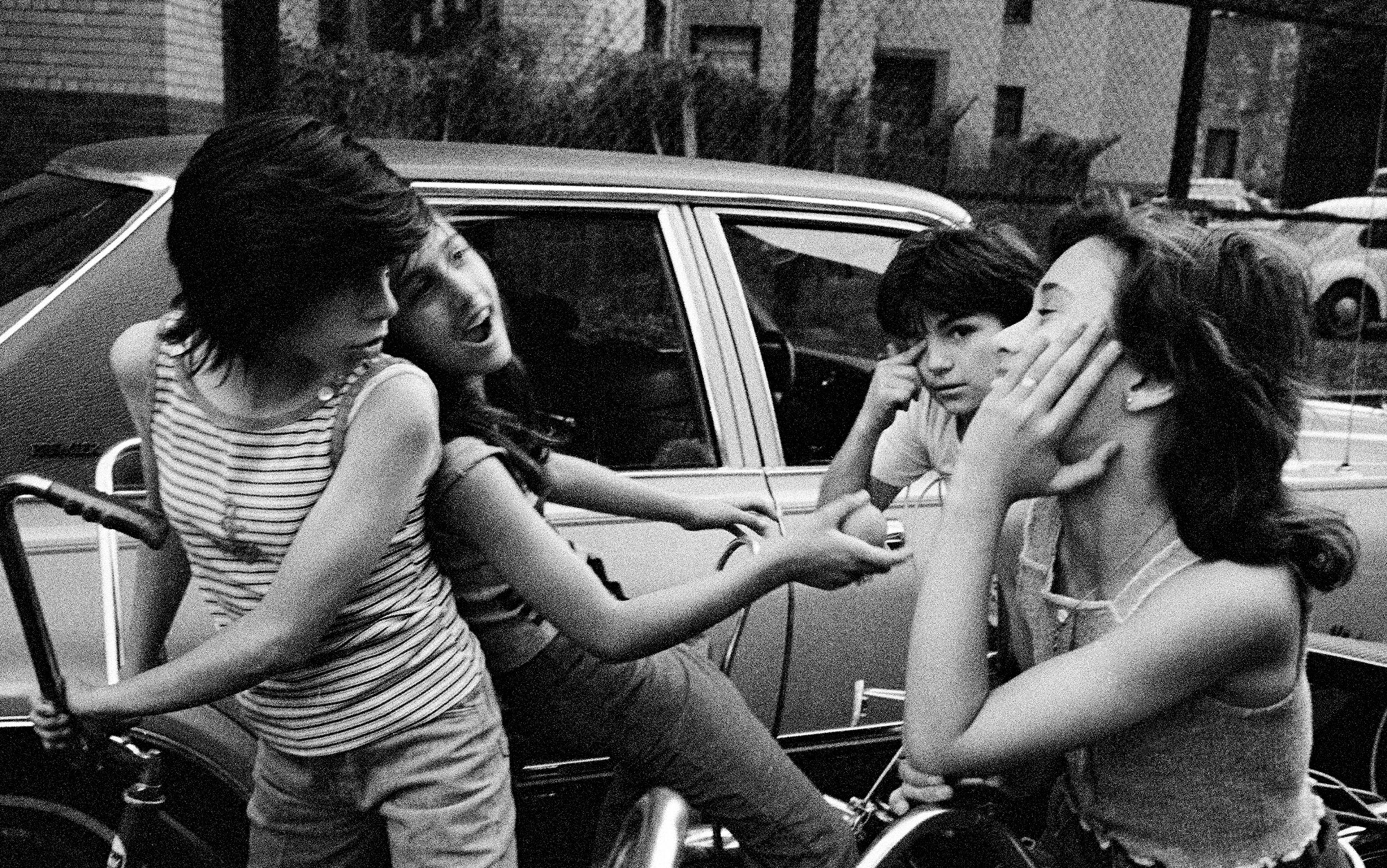

The present touch drought arrived after a period in which people were already growing more afraid of touching one another. Technology has enabled this distance, as social networking sites have become the primary source of social interaction for children and adolescents. A recent survey showed that 95 per cent of teens have access to a smartphone, and 45 per cent say that they are online ‘almost constantly’.

Another reason for touch-scepticism is the growing global awareness of how touch is a weapon that men use to impose their power over women. The #MeToo movement exposed how women are expected to acquiesce to inappropriate touch as the cost of gaining access to certain kinds of opportunities. Meanwhile, doctors, nurses, teachers and salespeople are all guided against being too ‘hands-on’. Yet studies suggest that touch actually improves the quality of our encounters with any of these professionals, and makes us evaluate the experience more positively. For example, we are likely to give a more generous tip to a waiter who absently touches our shoulder when taking the order than to those who keep their distance.

What’s unique about touch, when set against the other senses, is its mutuality. While we can look without being looked back at, we can’t touch without being touched in return. During the pandemic, nurses and doctors have talked about how this unique characteristic of touch helped them communicate with patients. When they couldn’t talk, smile or be seen properly because of their protective equipment, medical professionals could always rely on a pat on the shoulder, holding a hand or squeezing an arm to reassure patients and let them know that they were not alone. In a pandemic where touch is a proven vector, paradoxically it’s also a part of the cure. Touch really is the ultimate tool for social connection, and the good news is that we were born fully accessorised to make the most of it.

In the 1990s, there was a wave of research demonstrating the shocking consequences of touch deprivation on human development. Several studies showed that children from Romanian orphanages, who were barely touched in the first years of life, had cognitive and behavioural deficits later on, as well as significant differences in brain development. In adulthood, people with reduced social contact have a higher risk of dying earlier compared with people with strong social relationships. Touch is especially important as we age: for instance, gentle touch has been shown to increase the amount of food intake in a group of institutionalised elderly adults. Even when we can’t see, hear or speak as we used to, we can almost always rely on touch to explore the world around us, to communicate with others, and to allow them to communicate with us.

Science is now beginning to provide an account of why touch matters so much. Touch on the skin can reduce heartrate, blood pressure and cortisol levels – all factors related to stress – in both adults and babies. It facilitates the release of oxytocin, a hormone that provides sensations of calm, relaxation and being at peace with the world. Every time we hug a friend or snuggle a pet, oxytocin is released in our body, giving us that feel-good sensation. In this way, oxytocin appears to reinforce our motivation to seek and maintain contact with others, which assists in the development of humans’ socially oriented brains. Oxytocin also plays a vital role in the relationship we have with ourselves.

In our lab, we recently showed that oxytocin might promote processes of multisensory integration, the so called ‘glue of the senses’ – the way the world typically presents itself to us as a coherent picture, rather than as multiple distinct streams of sense data. Multisensory integration, in turn, is at the root of our sense of body ownership, the feeling that most take for granted, that our body is ours. For our studies, we invited people to the lab, and induced the Rubber Hand Illusion, a well-established set-up where participants look at a lifelike rubber hand being touched while their own hand, hidden out of view, is touched at the same time. After a minute or so of synchronous tactile stimulation, the vast majority of participants experience the illusion that the rubber hand is their own hand, that they embody the rubber hand. We found that applying the tactile stimulation at slow, caress-like velocities enhances the illusion of embodying the rubber hand. Furthermore, we also found that giving participants one dose of intranasal oxytocin before the illusion enhanced the experience, compared with a placebo. In other words, affective touch and oxytocin might boost the process that keeps us grounded to a physical body.

Touch is the first sense to develop, and is mediated by the skin, our largest organ. We are one of the few mammals to be born so premature in the trajectory of our development. Our motor system isn’t fully developed, we can’t feed ourselves, we can’t regulate our own temperature beyond a certain threshold – all of which means that we rely on others to survive. As a child, being cared for depends primarily on tactile contact and ‘being held’. Any basic activity involves touch, such as changing nappies, having a bath, being fed, sleeping and, of course, cuddling. Even after we make it through the first few months of life, social tactile interactions are crucial for our development. For example, postnatal depression is known to have negative consequences for infants, but maternal touch can also have a protective effect. So encouraging tactile interactions between mothers with depression and their babies can reduce negative outcomes for the children later on in life. Importantly, the benefit is reciprocal: skin-to-skin contact between infant and parent increases the levels of oxytocin in mothers, fathers and infants, providing a feel-good sensation, promoting the development of a healthy relationship, and enhancing synchrony in parent-infant interactions.

Slow, caress-like touch was more likely to communicate love, even when delivered by a stranger

Many neuroscientists and psychologists believe that we have a dedicated system just for the perception of social – affective – touch distinct from the one that we use to touch objects. This system seems to be able to selectively recognise caress-like touch; this is then processed in the insula, a brain area connected to maintaining our sense of self and an awareness of our body. Slow, caress-like touch is not only important for our survival, but also for our cognitive and social development: for example, it can influence the way we learn to identify and recognise other people from early in life. In a study of four-month-old infants, when parents provided gentle stroking, children were able to learn to identify a previously seen face better than those who experienced non-tactile stimulation. It seems that slow, social touch might act as a cue to pay particular attention to social stimuli, such as faces.

What’s particularly important in infancy and childhood is not only the amount of touch we receive, but also its nature and quality. In a recent study, my colleagues and I showed that infants as young as 12 months are able to detect the way that their mothers touch them during daily activities, such as during play time or while sharing a book together. In our study, the mothers didn’t know that we were interested in touch, which allowed us to have a real insight into their spontaneous interactions. Importantly, we found that mothers’ ability to understand their infants’ needs translated into a kind of tactile language: for example, those mothers who were less aligned or responsive to their babies also tended to use more rough and restrictive touch. Infants also tended to reciprocate, in that they were more likely to use aggressive touch towards their mothers if this was the way that they were touched.

It’s not an exaggeration to talk of touch as a kind of language – one that we learn, like spoken language, through social interactions with our loved ones, from the earliest stages of our life. We use touch every day to communicate our emotions, and to tell someone that we are scared, happy, in love, sad, sexually aroused and much more. In turn, we are pretty good at reading other people’s intentions and emotions based on the way that they touch us. In a recent study, we invited people to the lab and asked them to detect the emotions and intentions that the experimenter was trying to convey to them via touch. The touch was delivered at different velocities: slower, as the touch typically occurring between parents and babies, or between lovers; or faster, a type of touch more common between strangers. We found that slow, caress-like touch was more likely to communicate love, even when the touch was delivered by a stranger. In contrast, participants didn’t attribute any special meaning or emotions to touch delivered at fast velocities. Interestingly, in the case of brain damage involving the insula, people have difficulties in perceiving affective touch, as well as disturbances in the sense of body ownership. This suggests the existence of a specialised pathway that arrives from the skin to a specific part of the brain.

We exchange tactile gestures as communicative tokens not only to build social bonds, but to establish power relationships. In professional Western contexts, people typically apply a certain amount of pressure in a handshake when meeting someone for the first time. A handshake stands as a proxy for competence and confidence; we feel the other person touching us, and ask ourselves: ‘Do I trust them enough to offer them a job?’ or ‘Should I let them babysit my kids?’ One study showed how a firm handshake was a key indicator of success in a job interview, perhaps because the handshake is the very first way that we close the physical gap between us and the other. The handshake is also used to seal an agreement, with the force of a signature or contract. The danger and vulnerability that’s intrinsic to touch is part of what allows it to serve this socially binding function; indeed, it’s believed that the handshake arose as a way of ensuring that the two people involved weren’t holding weapons.

The language of touch also affects the way that we relate to ourselves and our bodies across the lifespan, with profound impacts on our psychological wellbeing. In another set of studies, we investigated the way in which people with anorexia nervosa perceive caress-like touch as compared with healthy people. Anorexia nervosa is a severe eating disorder characterised by a distorted sense of one’s own body, but it can also lead to a reduction in social interactions. We wanted to understand whether the fact that sufferers report finding less pleasure in social interaction might be related to the disorder. Across two studies, we found that people with anorexia perceived slow touch delivered with a soft brush on their forearm to be less pleasant, compared with healthy participants. Importantly, we found the same pattern of results in people who have recovered from anorexia nervosa. This suggests that this reduced capacity to take pleasure in touch might be more of a stable characteristic rather than a temporary status, related to the severe malnutrition that we observe in anorexia nervosa. This finding, along with other studies, suggest that there is definitely a close link between social touch and mental health. Throughout our lives, we need touch to flourish.

So, what happens to our tactile fluency when we make touch taboo? At the times in our lives that we are most fragile, we need touch more than ever. From everything we know about social touch, it needs to be promoted, not inhibited. We need the nuance to recognise its perils, but avoiding touch entirely would be a disaster. The pandemic has given us a glimpse of what life would look like without touch. The fear of the other, of contamination, of touch has allowed many of us to realise how much we miss those spontaneous hugs, handshakes and taps on the shoulder. Physical distancing leaves invisible scars on our skin. Tellingly, most people mention ‘hugging my loved ones’ as one of the first things they want to do once the pandemic is over.

Touch is so vital that even the language of digital communication is saturated with touch metaphors. We ‘keep in touch’, and acknowledge that we are ‘touched by your kind gesture’. Some researchers have suggested that technology could enhance our physical connection with others, prompting new kinds of interpersonal tactile connections via hug blankets, kissing screens and caressing devices. For example, a project based at University College London is exploring how digital practices such as ‘Likes’ and emojis – signals that communicate emotional states and social feedback – could extend to the remote manipulation of textures and materials. Two people at a distance could each have a device that detects and transmits tactile feedback: for example, my sensor could become warm and soft when my partner on the other side of the world is available and wants to let me feel their presence, or conversely, it could turn cold and rough if my partner needs my presence.

Nothing can compare with the magic of a physically intimate moment with someone

There’s a lot of potential for these devices, especially for touch-deprived people such as the elderly, people who live alone, or children in orphanages. Consider that 15 per cent of people worldwide live alone, often far away from loved ones, and that statistics are suggesting that more and more people die alone, too. What a difference it would make to have the possibility of being physically close, even when far apart.

However, these devices should be complementary to the power of a skin-to-skin tactile exchange, rather than a substitute for it. Nothing can compare with the magic of a physically intimate moment with someone, in which touch is often accompanied by a cascade of other sensory signals such as smell, sound and body temperature. Touch is physically and temporally proximal, in that it means ‘we are close to each other and we are here now, together’. Unlike other senses that can be digitalised, such as seeing someone’s face and talking to them over Zoom, touch requires you to be in the same place, at the same time, with another human being. A digitalised version of touch would be missing this rich sharing of a specific moment in space and time, allowing a more limited experience of what a hug could provide. If I could potentially pause or retract from someone sending me a digital caress, that aspect of touch in which we ‘feel along with another person’ would fail.

In the current environment, is the idea of a ‘renaissance of touch’ just for the brave and the foolish? I don’t believe so, and scientific evidence speaks loud and clear. We lose a lot by depriving ourselves of touch. We deprive ourselves of one of the most sophisticated languages we speak; we lose opportunities to build new relationships; we might even weaken existing ones. Through deteriorating social relationships, we also detach from ourselves. The need for people to be able to touch one another should be a priority in defining the post-pandemic ‘new normal’. A better world is often just a hug away. As a scientist, but also as a fellow human, I claim the right to touch, and to dream of a reality where no one will be touchless.

To read more about the body and emotions, visit Aeon’s sister site, Psyche, a new digital magazine that illuminates the human condition through three prisms: mental health; the perennial question of ‘how to live’; and the artistic and transcendent facets of life.