White and silent, death is undoing everything. For years, the 20 or so families in the tiny riverside settlement had lived hard yet improving lives, clearing the forest around them, fishing the waters, planting crops and building houses. Birth by birth, the population grew. From time to time, trading boats came down the river, but otherwise the wider world did not intrude and the people sought no part in it.

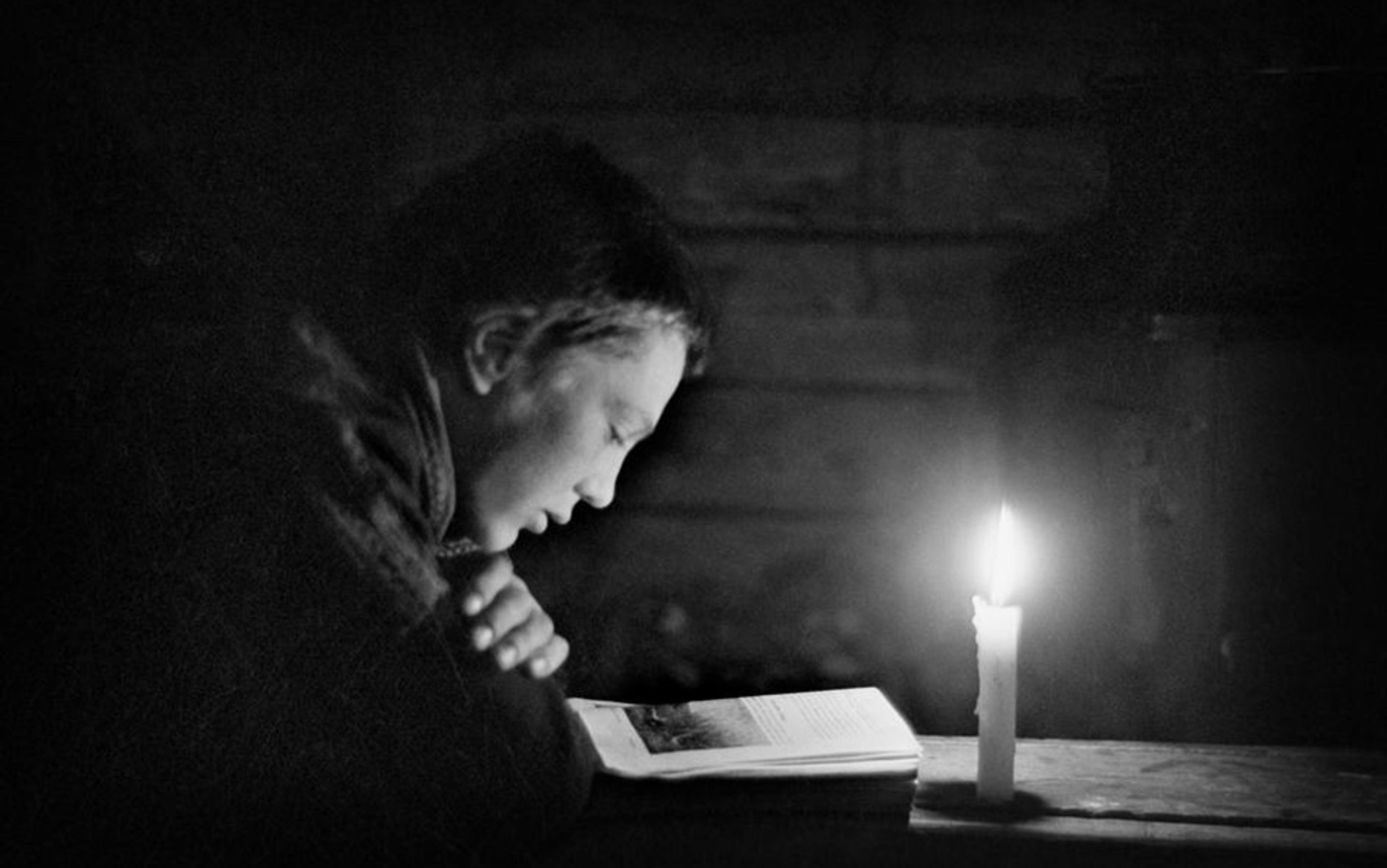

The crisis came rapidly, with little warning: first, a hungry summer as the previous year’s stockpile of food ran out weeks ahead of the harvest; now, a catastrophic winter. Under a blanket of snow, the villagers are starving. Weak and diminishing, the population cannot fell enough trees to keep up the supply of firewood, and so they are freezing to death as well. The sounds of industry die away. Smoke stops rising from the chimneys. The scene is peaceful, but it is one of horror.

This is a fairly typical outcome for a game called Banished, released last year by a microscopic US developer called Shining Rock Software. Banished was a surprise hit on Steam, a retail platform that accounts for more than half of all online sales of personal computer (PC) games. The success was surprising given the title’s fundamental simplicity of concept, its rage-inducing difficulty of play, and its unblinking bleakness. It is a real-time ‘god game’ in which the player guides a small group of people in building a small village, which with careful guidance can become a small town. The available buildings and technology suggest it is the Middle Ages, and the steep pitched roofs, encircling forest and harsh winters suggest northern Europe. We know that these people have arrived in a clearing with little more than the clothes on their backs and some seeds because they have been ‘banished’ from elsewhere. Other than that, there’s little context or backstory; and there’s no time to ruminate because Winter Is Coming.

All strategy and resource-management games involve crises and shortages, but put a foot wrong in Banished and everyone dies. It’s a brutal lesson in the wretched economics of subsistence farming. The workers are desperately unproductive, their hovels are draughty, their winter coats are thin, and their iron tools wear out. All it takes is the slightest misallocation of labour or materials, and every man, woman and child is doomed: output dips, there are one or two untimely deaths, and all of a sudden there aren’t enough hands to bring in the harvest, and potatoes rot in the fields while the whole village dies in their beds.

Banished is a horrible game, full of heartbreak and woe. Why would anyone play it – much less in large enough numbers to make it a hit? The simple answer is: because it is excellent. A more sophisticated answer might note that it is also an exquisite example of what Jesper Juul, associate professor in the School of Design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, calls ‘the paradox of failure’, arguably the central mystery at the heart of computer games as a medium. The paradox has three parts:

1. We generally avoid failure.

2. We experience failure when playing games.

3. We seek out games, although we will experience something that we normally avoid.

This paradox doesn’t apply just to games: many kinds of art, particularly tragic literature and drama, expose us to painful emotions that we seek to avoid in everyday life. ‘The paradox is not simply that games or tragedies contain something unpleasant,’ Juul writes in The Art of Failure (2013), ‘but that we appear to want this unpleasantness to be there, even if we seem to dislike it.’

Indeed, this unpleasantness must be present in games: players want games to be challenging and will not return to one that is too easy. And in games we are not just vicariously experiencing the failures of a fictional protagonist – a Hamlet or an Anna Karenina – but our very own failures. It is, after all, our own skills that come up short. On these grounds, Juul calls video games ‘the art of failure’ – the singular art form that sets us up for failure and allows us to experience and experiment with it.

So it’s not constant failure on the part of the player that sets Banished apart. What is different about it is its persistent atmosphere of scarcity, and the sweat and toil that must continuously go into avoiding shortages – shortages that can never be entirely eliminated.

This is particularly unusual for a god game. While the genre often involves minor shortages of this or that, these are usually present simply in order to give playable variation to an overall environment of plenty. Scarcity, in the classic god game, is merely a temporary condition to be overcome; the game is resource management, not desperately eking out resources, or watching them dwindle without replenishment. And yet Banished is far from being the only new game that seems to make a virtue of such hard necessity. In fact, across a range of new titles, austerity abounds. Why?

The Steam platform, which helped to drive Banished’s success, has done a great deal to democratise game development and marketing, giving small designers a better chance of competing against industry giants and facilitating viral, word-of-mouth hits. Steam has given PC gamers and developers a better than ever idea of what is really popular among their peers, spawning copycats and crazes. And something interesting has become clear: scarcity sells. To put it more precisely: scavenging sells. Starvation sells. Survival sells.

Nether, Rust, Infestation: Survivor Stories, Miscreated, 7 Days to Die, The Long Dark, The Forest – the past couple of years have seen a spate of survival games, often but not always with a voguish ‘zombie apocalypse’ setting. On the surface, these resemble that perennial favourite, the first-person shooter, in which the player runs around killing zombies, terrorists or other players. But they share a new emphasis on brutal realism and necessity. Ammunition is no longer conveniently scattered along a linear path towards an objective; often, there is no particular objective, as the games are generally what is called ‘open world’, providing an extensive omni-directional living terrain that the player can freely explore. Sometimes, ammunition is the least of your worries because your only weapon is a rock and your character is starving and bleeding to death. This is no cheerful blastalong, but a twilit limp along a grass verge, bleeding from a septic wound, weak from hunger, pursued by assailants against whom you have no realistic defence. Horrible, but utterly compelling.

As a tribute to the proliferation and popularity of these games, the UK-based games website Rock, Paper, Shotgun recently ran a ‘Survival Week’ celebrating and exploring the nascent genre. Jim Rossignol, the site’s founder, points to the zombie-apocalypse simulation DayZ (2013) – originally a modification to a fairly routine military simulation called Arma 2 (2009), then a game in its own right – as a seminal force in the trend, although ‘it seems that a number of developers were all reaching similar conclusions around the same time’. It’s hard to definitively trace all the entwined threads that led to this outbreak, but Rossignol mentions a steady growth in interest in so-called ‘roguelike’ games, named for the primordial ancestor of the survival game, Rogue (1980).

finding a mouldy crust of bread to eat is often a higher priority than blazing away at the robots

Other strands are the decade-old fascination with the zombie apocalypse in broader popular culture and the steady rise of non-linear ‘open worlds’ in games culture, combined, Rossignol says, with ‘an expanding interest in walking, hiking and exploration as a basic gameplay mechanic’. A crucial waypoint down this road towards a playable version of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road might be the critically and commercially successful Fallout series (1997-present), which placed open-world exploration in a parched nuclear wasteland; its most recent iteration, Fallout: New Vegas (2010) was set in the Nevada desert and included a hugely challenging survival mode in which exposure, dehydration and starvation were as big a menace as the roaming gangs and mutant wildlife typical of the series.

Possibly more important is the spectacular blockbuster that is Minecraft (2009-11), a Swedish game that is best known as a construction toy with cutesy 8-bit graphics, but one with pronounced survival and scarcity aspects. A player’s first night in the game is generally spent cowering in a crude dirt shelter while horrors claw at the door; hunger is a crucial game dynamic.

Rossignol has in fact developed and released his own contribution to this new genre, a game called Sir, You Are Being Hunted (2014), in which the player is pursued across a rural British landscape straight out of The Thirty-Nine Steps or Rogue Male. Here, however, the pursuers are tweed-jacketed robots. The cutesy Wodehousian steampunk aspects of the game do little to soften its uncompromising survival mechanics, in which finding a mouldy crust of bread to eat is often a higher priority than blazing away at the robots and hiding and fleeing is nearly always the most sensible strategy. (But the humorous elements cannot be denied; perhaps this is even a new sub-subgenre, along with Minecraft and the Tim Burton-esque Don’t Starve (2013): survival whimsy.)

For Rossignol, ‘scarcity in survival games is a psychological foundation which changes the nature of the experience’. Ammunition and health, which diminish as the player encounters enemies and must be resupplied, have long been a basic part of games but, as Rossignol says, they don’t deplete if you stand still doing nothing. ‘In a survival game, you will essentially die via inaction, as you would in life. This means that the actions you take are given a completely different hue than in an action game.’ He notes, for example, the Russian game Pathologic (2005), in which food is so scarce that one of the first things a player is likely to do is trade his gun for some milk.

Vulnerability becomes a more prominent part of the game’s emotional palette than, say, bloodlust or vengeance. In a strange way, the survival genre is a sort of disempowerment fantasy, and this opens up genuinely fascinating narrative possibilities, at last breaking away from the technicolour militarist bloodbaths that dog the reputation of computer games. Take, for instance, This War of Mine (2014), developed in Poland and inspired by the Sarajevo siege during the civil war in Bosnia in the 1990s. The player is in charge of keeping an unarmed group of refugees alive. By day, they are confined to a shelter by sniper-fire; at night scavenging can take place, which is dangerous but does not necessarily call for violence on the part of the player.

But there is another important atmospheric factor in play: aesthetics. This War of Mine is distinctive and beautiful on the screen – the player moves through cutaway buildings, a mosaic of shattered rooms, rendered in muted and desaturated tones, pierced by heatless light. The growing forests, grazing deer and snow-covered roofs of Banished are extremely pretty. Games such as S.T.A.L.K.E.R: Shadow of Chernobyl (2007) and Sir, You Are Being Hunted take place in moody landscapes that are equally rich in the kind of scenic interest that keeps the player trudging towards the horizon and a sense of ever-present danger. But we cannot pause too long to enjoy our surroundings: their visual appeal is often most noticeable at the moments of gravest danger, pinned behind a wall by enemies, watching a ridgeline, knowing that death is coming. Starving, admiring the way the grass sways. Presiding over our doomed village, its fires going out, entranced by the peace of midwinter.

Perhaps this combination of exquisite attention to environmental detail and nature, combined with the harshness of the game machinery, can be interpreted as a new strain of romanticism in game design. It reveals a commitment to rewards much more nuanced than simple success and failure – a kind of splendid, attractive failure akin to tragedy. In a medium that is not often home to much in the way of depth, this new subtlety is as refreshing as a cool glass of water.

‘Most games are ultimately designed to let you win, but here the systems conspire to make your death interesting,’ Rossignol says. These games subvert the usual arc of heroic triumph by providing a basis for interesting, beautiful defeat. ‘Players like to tell stories of what they’ve seen or done in games, and in survival games it’s often the extreme way that the systems provide for your death which make for the most interesting tales. They even have an element of dark humour to them: the repetitious beat of being eaten by a wolf in the The Long Dark has become something of an in-joke.’

It’s tempting to draw a broader sociological trend from the sudden popularity of scarcity in games. Perhaps it reflects a psychological need, barely conscious, to roleplay shortages and breakdowns that we fear might soon occur in the real world. At times, Banished comes across like a lesson in fragility – that even a simple economy is a sum of interdependent parts, the failure of any one of which could spell catastrophe. More than once, it wasn’t really starvation or hypothermia that killed my village, it was a shortage of good tools: as the blacksmith struggles to keep up with demand for equipment, the workers’ tools wear out, the supply of timber and iron drops, and the blacksmith keeps running out of raw materials; meanwhile, his tools are wearing out too, and without much delay the production of food and firewood collapses and everyone dies.

game design might be exhausting the possibilities of more and increasingly discovering the power of less

Or it is demographics that slits your throat: a combination of epidemic and hunger manages to kill a disproportionate number of younger workers, and suddenly your population is unbalanced and failing to replace itself. That’s a slower death – a village of geriatrics wasting away – but no less awful to contemplate.

Equilibrium with the environment, even dynamic equilibrium, is nigh impossible to achieve. Develop a large enough town to build a town hall, and you can gain access to statistics and graphs that show your settlement’s slow accretion and periodic massive shocks. It is striking how closely these resemble the infamous chart from the Club of Rome report The Limits to Growth (1972): output and population accelerate, peak, and abruptly collapse. That chart still hangs over our civilisation, part-warning, part-prophecy: with one side of politics preaching economic ruin and the other environmental ruin, it is hardly surprising that a taste for austerity has crept into playtime.

Post-apocalyptic scenarios often have undertones of amoral consumerist wish-fulfilment, in which we roam the shopping malls and other treasure houses of the modern world and take whatever we want, blasting anyone who gets in our way. Survival games are, at least, a little more honest about the challenges of such a situation and an individual’s chances within it. But perhaps it’s better just to focus on what this phenomenon means for this immature art form. With technological limitations falling away, game design might be exhausting the possibilities of more and increasingly discovering the power of less.

At the heart of the new digital melancholy – wrapped in all that beauty – is primal simplicity, the basic animal equation: eat, don’t get eaten, keep going. The value of that simplicity, the playability of it, perhaps we could even say the fun of it, is watching the unexpected ways this elemental calculus can work itself out. And there is more watching involved. Vulnerability imposes a measure of passivity – in some situations, for instance, the only workable strategy might be to wait for danger to pass, to hide behind a hedge, to stay in the shelter until dawn or nightfall – so the environment and the atmosphere become more important, they are not just a Niagara of garish detail to be rushed past. There is a world to be experienced, and we must learn our place in it.