Vienna, 1912. It is autumn, and the city’s fin-de-siècle extravagance is approaching its peak. On the stage of the city’s pre-eminent concert house, the Musikverein, the mute and melancholy clown Pierrot, the star of Arnold Schoenberg’s atonal melodrama Pierrot Lunaire, is drinking moonlight – the stuff of intoxicating artistic inspiration – with his eyes. The moon-drunk aesthete soon becomes disillusioned: stigmatised and abused by an intolerant society (a part played unwittingly by the audience at the Musikverien), Pierrot retreats from the world, floating home in a boat, following the trail of an ancient scent back to his dreamy, distant home in Bergamo. Featuring a small chamber ensemble and a spoken-sung part for a reciter, Pierrot Lunaire is a grotesque parody of the cabaret style. It is also allegorical and autobiographical: Pierrot, moon-drunk and doomed from the start to be misunderstood and unappreciated, is the epitome of the modern artist at the turn of the century.

In this incarnation, Schoenberg’s Pierrot – as the artist desperately seeking new means of expression in the modern world, while at the same time vilified by that world – neatly encapsulates the feverish and often contradictory spirit of Vienna in the early decades of the 20th century. A much-romanticised era for the city, these years are commonly celebrated as a period of explosive artistic, literary, intellectual and especially musical modernisation in which resolutely iconoclastic geniuses such as Schoenberg, Sigmund Freud, Gustav Klimt and Alfred Schnitzler broke with the past in order to lay the groundwork for the future. In this narrative, Vienna’s musical revolution was especially radical: Schoenberg’s Pierrot was later characterised by Igor Stravinsky as ‘the solar-plexus of modern music’ – the culmination of a shift away from tonality and hundreds of years of classical music, in favour of a new music for a new century. But how did this happen? How did Europe’s ‘city of music’ – the home of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms – become the birthplace of an explosive musical modernism that threatened to destroy the very tradition to which it belonged?

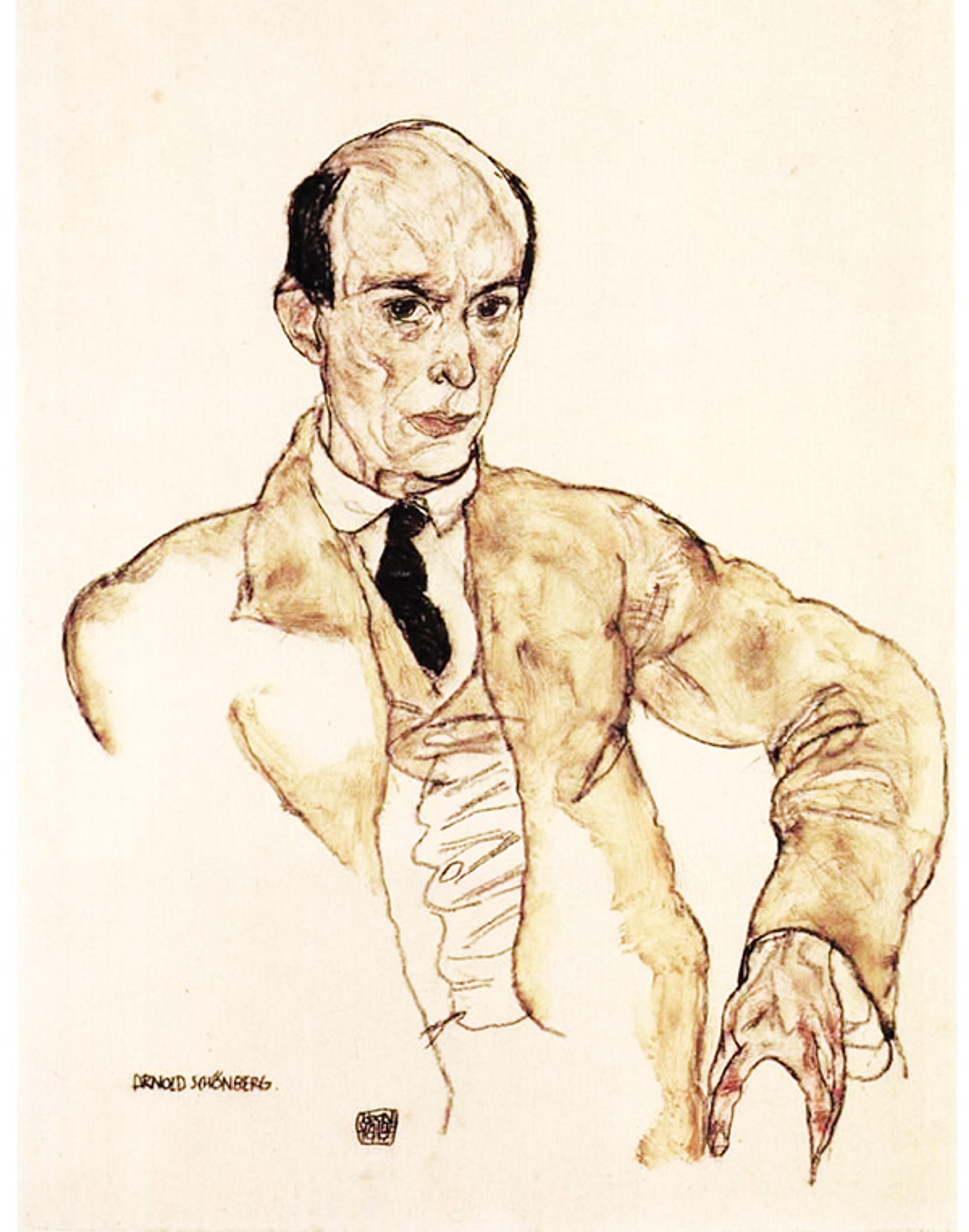

Portrait of Arnold Schönberg (1917) by Egon Schiele. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

The history of Viennese music and culture is knotty because it has been interwoven with clichés about a singular ‘Viennese way,’ namely ‘Gay Vienna’: a city of charm, sentimentality and light-hearted nihilism. It is an enduring and popular characterisation of the city’s cultural history. It is also a fantasy. ‘Gay Vienna’ might provide a comforting suturing-up of historical complexities, but, as the musicologist Seth Brodsky at the University of Chicago might argue, such fantasies themselves must be un-sutured in order to restore a portrait of a time and place that is much messier, but also closer to the truth.

Fin-de-siècle Vienna, or ‘Vienna 1900’ – the period spanning roughly 1890-1913, including the emergence of the Wiener Moderne – has become a kind of fantasy space, problematic but also fascinating. Scholars began taking a serious interest in Vienna 1900 only in the 1960s. Since then, some have elected to paint a portrait of turn-of-the-century Viennese culture – which includes the advent of modernism and expressionism in the visual arts, literature and music, under the intoxicating influence of psychoanalysis and its insights – as having emerged out of a utopian melting pot of different aesthetics, ethnicities and ideologies, somehow blending together to emerge as something ‘new’. For others, Vienna 1900 is an era of radical fragmentation and dissolution, in which sociopolitical, psychological and aesthetic notions – of social hierarchies, the self, the painted world, the tonal realm – are pulled apart in a cyclone of radical innovation.

A better explanation brings these two contradictory views together: Vienna is a city of paradoxes, its culture catalysed at crucial moments by crisis, tense mutual influence, and a fundamental if unresolvable agon – between individuals and institutions, between past and present, between tradition and modernity. Led by Schoenberg and his acolytes, the emergence and flowering of modern music in Vienna – the dissonance and expressive extremes of which remain relentlessly ‘modern’ and still largely unpalatable more than a century later – is emblematic of the tensions that fuelled the cultural flourishing of the city from the turn of the century to the start of the First World War.

Vienna’s musical and cultural supremacy is often correlated to its status as an imperial city, especially during the twilight period of the Habsburg dynasty from Emperor Joseph II in the late-18th century to the long reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I from the mid-19th century until the First World War. This is an important part of the story, if something of a catch-all explanation. A recent profile in The Economist proclaimed Vienna ‘the city of the century’ and asserted that its distinct ‘intellectual tang’, especially in the fin-de-siècle period, derived from its imperial pedigree. In this account, artists and intellectuals were drawn to the city by the magnet of empire: once there, they simply blended like hot milk and coffee in a traditional Wiener Melange, their different origins, ideas and identities dissolving to produce ‘something fresh’. This coffee analogy, while tempting, fails to take into account the factionalism of Vienna’s artistic and intellectual strata – not to mention its territorial Kaffeehaus culture – and the fetishising of priority by its denizens, many of whom were much more interested in protecting their originality than blending with others. It also ignores the fact that the city has not always been a cultural powerhouse, despite an imperial legacy that far predates the turn of the century.

Vienna’s imperial lineage – its association with empire, at least – can be traced back to the city’s founding. Then known as Vindobona, it was a Celtic settlement before it was incorporated into the Roman Empire in the 1st century CE. Vindobona became a large military base with a substantial civilian settlement, and served as a key component of the empire’s northernmost frontier along the Danube until the 5th century. Following a period of several centuries of decline and relative obscurity after the fall of the Roman Empire, Vienna re-emerged as an important site for trade. Falling under Habsburg rule in the 13th century, it quickly rose to prominence, becoming a university city, a bishopric and ultimately the capital of the Holy Roman Empire in just 200 years. Vienna served more or less continuously as the seat of the Holy Roman Emperor from the 15th to the early 19th century, when it became the seat of the Emperor of Austria. It remained an imperial city until 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed at the end of the First World War.

A century after its collapse, the vestiges of the empire are still present in the looming neoclassical and neogothic buildings that draw so many tourists here: to the parliament building, city hall, the university, the art history museum, the museum of natural history, the national theatre, the opera house and the imperial palace. These buildings – their towering Greco-Roman columns and mythology-inspired statuary linking antiquity with the Habsburg dynasty – were erected by Emperor Franz Joseph in the 19th century. They encircle the oldest part of the city along the Ringstrasse – the tree-lined boulevard where the fortified city walls once stood – and form part of the bewildering array of architectural styles that characterise contemporary Vienna. Even Stephansdom, the huge, iconic cathedral in the centre of the old city, attests to Vienna’s complex history: nestled among ultra-modern buildings and high-end shops, the medieval foundations of St Stephen’s support a millennium’s worth of spiky gothic, baroque and neogothic add-ons, a hodgepodge that challenges the eye to situate the cathedral in time and space. Something similar could be said for the city’s musical history. The Viennese music critic Max Graf wrote in 1945: ‘As from the pages of an old chronicle, from its buildings one can read the history which shaped Vienna into a great musical city.’

But Vienna was not always Europe’s ‘city of music’. Paris would have owned that title through the late Middle Ages, thanks to the flourishing of polyphony associated with Notre-Dame. Competition for the title came from the Burgundian courts in the late Renaissance, and from the Italian city states during the latter part of the 16th century. According to Graf, sometime in the early 17th century Vienna took over as the continent’s ‘capital city of music’, making music ‘not just for the Danube valley or for Austria, but for the whole of Europe, nay, even for the world.’

Mozart was viewed with ambivalence by his Viennese audiences, and died impoverished there

However, Vienna began promulgating itself as ‘the city of music’ – Musikstadt Wien – only about 200 years ago, sometime in the first half of the 19th century. It is difficult to reconcile with Graf’s claim of 17th-century Vienna as a musical metropolis. In purely practical terms, it was small at that time, with perhaps a fifth of the population of other major European cities, such as London and Paris. And while Baroque Vienna was certainly awash in music, it was imported. The rage at the Habsburg court (hardly ‘in the air’ of the city, but rather exclusive to the aristocracy) was Italian music, especially the new genre of opera, which had begun to spread northward into central Europe from Venice by the mid-17th century.

The perception of Vienna as the birthplace of musical classicism – that is, of a universal musical language and canon of great works, brought to its apotheosis by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven – was created retrospectively by Austrian musicologists in the 20th century. This Viennese classical style, or Wiener Klassik, refers to a generalised set of musical textures, structures and aesthetic standards, a common idiom of organic traits, comprising a sort of family resemblance that dominated the music of the late-18th century. It consists of homophony (melody over slow-moving harmonies); short, regular phrases; tonal stability; formal clarity; and a delicate balance between energy, expression, refinement and restraint, achieving what the Viennese musicologist Guido Adler called ‘the fundamental note of true Viennese classical music … a metaphysical blend of the serious and the gay’.

With respect to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven – the members of the putative ‘First Viennese School’ – the ironies abound. None of these masters of Viennese classicism were Viennese: Haydn was from lower Austria and spent much of his working life away from the city in what was then Hungary, in the service of the princes of the Esterházy family. Mozart was from Salzburg, and Beethoven was from Bonn in Germany. None of these composers would have been considered ‘classic’ in their lifetimes and, if anything, late-18th-century audiences would have identified an expressive, romantic quality to the works of Haydn and Mozart, and especially in Beethoven’s music of the early 19th century. Moreover, of these three masters, it was Haydn – the least-known and least-performed of the First Viennese School – who was for many years the most famous and influential by far. Mozart, by contrast, who has since become the symbol of Viennese classical music, if not the city itself, was viewed with some ambivalence by his audiences, and he struggled to make ends meet in the city of music, dying impoverished there in 1791. Beethoven was a decidedly divisive figure in Vienna, and his music sometimes caused audiences and critics to question his taste, if not his sanity (some Viennese musicians even refused to play Beethoven’s music, claiming it was too complicated, too long, or too cacophonous).

Even though the great Viennese journalist and critic Karl Kraus claimed in the early 20th century that the Viennese preferred to live as though it was perpetually 1830, Vienna has always been a dynamic city, never one stuck in time. Over the 19th century, the population ballooned from about 250,000 inhabitants to reach 2 million in the early 20th century, and the middle class and especially the Jewish professional and intellectual class blossomed. The city received a massive architectural facelift and incorporated its outlying suburbs into the city proper, while its political landscape saw the long dominance of liberalism gradually give way to aggressive pan-Germanist and antisemitic ideologies by the end of the century. With respect to music, many of these changes matter. The growing bourgeoisie, long periods of peace, economic stability and a gradually modernising economy led to the expansion of music education, the growth of public music societies, and the construction of many new public performance venues, such as the Konzerthaus, the Musikverein and the Volksoper (the Vienna People’s Opera). Jewish composers, conductors and musicians also began to reshape Viennese musical culture, even while antisemitism festered.

In the context of all of this growth and development over the course of the 19th century, the idea that Vienna’s cultural and intellectual supremacy – its ‘particular intellectual tang’ – can simply be tied to its status as an imperial capital needs some rethinking. Imperial influence and patronage was on the decline through the 1800s, and the city’s conflicting political ideologies and class tensions made for a polity barely held together by a fraying monarchy and the fantasy of empire. Vienna 1900 emerged from the turmoil of the 19th century as a whirlpool of contradictions, recently described by the historians Wolfgang Maderthaner and Lutz Musner as simultaneously a ‘laboratory of the Apocalypse’ and ‘the birthplace of epoch-making modern trends and achievements’.

Fin-de-siècle Vienna is sometimes referred to as ‘Freud’s Vienna’, a shorthand that doesn’t fully accord with the historical realities. At the turn of the century, Freud was not the towering figure he is today, and he was dismissed by the conservative Viennese medical establishment as a libertine and a bit of a quack. Nonetheless, ‘Freud’s Vienna’ points usefully at the notion of Vienna as the birthplace of ‘the modern mind’, when there was a decisive turn ‘inwards’. Just as Freud’s psychoanalytic theory was proposing that the truth of human experience was buried in the unconscious, that female sexual desire was an especially potent and mysterious force, and that libidinous instincts shaped our thoughts – awake or in dreams – and drove our actions, so too were the Viennese cultural avant-garde exploring these same issues, taking the same interior journey. The Wiener Moderne, at its core, is about the self – or, as Heinz Kohut, the Austrian-born psychoanalyst, put it in 1971, a ‘reshuffling of the self’ – revealed in the probing and unforgiving self-portraits of artists, in the literary works whose psychonarratives are created from internal monologues, and in the music that aspired to be the language of the unconscious itself.

Thinkers jealously guarded their ideas, and sought to protect themselves from the influence of contemporaries

The psychologically driven fine art of Vienna 1900 is epitomised by the paintings of Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka. By turns erotic and grotesque, ornamental and bare, this art is unflinchingly realistic in its depictions of human desires, frailties and suffering. At the same time, these artists depicted their all-too-human subjects as strangely decontextualised and alienated. In 1897, Klimt, who would become one of Vienna’s most renowned painters, led a breakaway movement of artists known as the Vienna Secession, who rejected the conservatism of the city’s art institutions and their inherited traditions of realism and naturalism. In his paintings, Klimt turned to symbolically rich depictions of female sexuality, desire and death, alluding to the fraught landscapes of the psyche otherwise hidden behind Vienna’s facades and repressive bourgeois respectability. Klimt’s protégé Schiele was an early expressionist, and his paintings – many of which are explicit nudes and self-portraits – are raw, austere, anxiety-ridden explorations of the darker depths of humanity. Kokoschka’s aggressive, sometimes violent expressionism sought, like Schiele’s, to represent inner essence and psychological truth.

The travails of Vienna’s modern artists reveal something important about the city’s cultural climate: not only the leftover petit-bourgeois Biedermeier aesthetic sensibilities of the mid-19th century, but also the ceaseless pitting of the creative individual against highly conservative institutions and institutional attitudes. Klimt was censured by the scandalised officials of the University of Vienna after being commissioned to paint three large murals for the faculties of medicine, philosophy and law, and took the paintings back. Schiele was arrested and imprisoned for painting nude portraits of young girls. Kokoschka, branded a ‘public terror’, was expelled from the Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna’s School of Arts and Crafts) for his iconoclastic views.

Schnitzler, a physician and a writer, examined many of the same themes as Klimt, Schiele and Kokoschka in literature, depicting the fabric of respectable, middle-class Vienna torn apart at the seams from the pressures of the libido, and using psychoanalytic-inspired devices such as stream-of-consciousness and interior monologue to capture the psychological reality of the characters in his plays, novels and short stories. Freud knew Schnitzler but he carefully avoided the writer because he recognised too many similarities between his own psychoanalytic enterprise and Schnitzler’s writing and thought. This is another defining facet of the culture of Vienna 1900: many of the city’s great thinkers and creators often jealously guarded their ideas, and sought to protect themselves from the undue influence of their contemporaries.

In the realm of music, Vienna’s most vital and valuable cultural commodity, the upheavals of the Wiener Moderne were registered and felt most acutely in Schoenberg’s music. Schoenberg is still known today as the bogeyman of modern music, even though he has been dead for nearly 70 years, and many of the works from his oeuvre that continue to vex classical-music listeners were composed more than a century ago. Whereas the modernist art of Vienna 1900 remains a huge tourist draw (dodgy reproductions of Klimt’s art can be found everywhere, and the city’s major art museums all have standing exhibitions of Klimt, Schiele and their contemporaries), the modern music of this same period has precisely the opposite effect. Its difficult dissonances and expressive extremes make it largely inaccessible and even repulsive to many concertgoers. Schoenberg is one of Vienna’s most important composers, and easily one of the most influential of the 20th century, but he also shoulders the reputation of composing ‘anti-music’.

He is also an unusual figure in the city’s pantheon of great composers. Born in Vienna in 1874 into a lower-middle-class Jewish family, Schoenberg didn’t receive a formal music education. He learned the violin as a child, later switching to cello (he was reputedly a poor cellist and probably had only rudimentary skill on the piano). As a young man, he received some informal instruction in harmony and counterpoint from friends, but otherwise appears to have been entirely self-taught as a composer.

Schoenberg’s early works – most notably his string sextet Transfigured Night, Op 4, composed in 1899 – are remarkable for their sophistication and maturity, but even more so for their absorption of Wagnerian and Brahmsian techniques. The Wagner-Brahms polemic – a heated debate in Vienna between progressive and conservative viewpoints – largely defined the city’s musical culture when Schoenberg was coming of age in the latter part of the 19th century. The Wagnerians heralded Wagner’s music, especially its expansive chromatic language and emotional depth, as the future of music. Brahms’s music was venerated for its conservative, neoclassical values and for its rigorous integration of musical ideas. Schoenberg didn’t take a side in this polemic. Rather, he combined Wagner’s rich harmonies and expressive depth with Brahms’s densely woven motivic textures. His music was thus paradoxical from the start, born of the most radical and most conservative musical thinking of the time. Along with his students Anton Webern and Alban Berg, Schoenberg would become the founder of the ‘Second Viennese School’.

Beginning in 1908, Schoenberg took a decisive stylistic turn towards what is now called ‘atonality’, which describes the dissolution of the hierarchical structures of the tonal system. What this meant in practice was the abandonment of keys as organising principles in a composition. As a corollary, traditional, key-based harmony – a common language in use since the time of Johann Sebastian Bach – no longer functioned. In its place, Schoenberg advocated the ‘emancipation of dissonance’, in the name of expressive necessity: all pitches would be equal, and the very concept of dissonance would disappear, yielding new and modern-sounding music intended to express the feelings and inner world of the modern man.

Writing to the pianist Ferruccio Busoni in 1909, Schoenberg passionately articulated his radical manifesto of modern music, which seemed to sweep away the past – and the kitschy artifice of light music – in its insistence on newness, psychological substance, immediacy and truth:

I strive for: complete liberation of all forms

from all symbols

of cohesion and

of logic.

Thus:

away with ‘motivic working out’.

Away with harmony as

cement or bricks of a building.

Harmony is expression

and nothing else.

Then:

Away with Pathos!

Away with protracted ten-ton scores … and other massive claptrap.

My music must be

brief.

… not built, but ‘expressed’!!

Schoenberg, implicating his contemporary Freud, would also advocate for freedom from ‘conscious logic’, and for music to connect with the subconscious.

The product of this radical modernism was some of the most astounding music of the 20th century, channelling the zeitgeist of Vienna 1900 through its belief that art should come directly from the unconscious, unmediated by the artifices of technique, form and tradition. Schoenberg’s music of this brief period – from 1908 until 1912 – represents the advent of Viennese modern music: born of trauma, deeply subjective, with stream-of-consciousness fluidity and governed by the logic of the unconscious. The texts and subtexts that accompany these works are mostly about destroyed love and the alienation of the artist, narrating Schoenberg’s own contemporaneous and often-imbricated personal and artistic crises.

Vienna as a city in which a number of contradictory things can be true at the same time

This manner of composing ultimately proved unsustainable because it needed continuous crises for fuel. Moreover, while it was perhaps therapeutically necessary for Schoenberg to compose it, the music itself – a seemingly chaotic kaleidoscope of dissonant sounds, driven by subjective impulses and exploring inaccessible psychological terrain – didn’t earn him many fans among conservative Viennese audiences. It provoked scandalous riots in the concert halls of the city, and his many critics accused him of making purposefully ugly music and promoting ‘ein Ästhetik des Hässlichen’: an aesthetic of the hideous. He became the supposed destroyer of Vienna’s precious musical inheritance (an ironic accusation, given that Schoenberg is the only composer in Vienna’s legacy of great masters, aside from Schubert, to have actually been born in the city).

This brings us full circle, back to the notion of the ‘city of music’ as something more like the ‘city of paradox’. Just as Vienna’s architecture keeps the past and present in constant juxtaposition, as Freud’s theory situates the past as ever-present beneath our consciousness, and as Klimt’s modern painting aesthetic took inspiration from ancient Egyptian art and Byzantine mosaics, so Schoenberg-the-destroyer was in fact deeply reverential towards his musical forebears. He insisted that new art does not replace or destroy the old. When an artist makes something new, he is in fact demonstrating his deep and intimate love for his predecessors. In Schoenberg’s view, his new music was not revolutionary: it was simply the next stage in an evolutionary process that could be easily traced back to Bach, if listeners would only make the effort. For Schoenberg, the history of great art was not to be repudiated in the name of the modern. The history of great art was the history of the new.

In examining Vienna’s cultural legacy, and especially its zenith during the fin-de-siècle period, my intention is not to debunk or demythologise. Vienna’s mythos is part of its beauty. What is necessary, though, is to understand the complexity of this legacy, and that there is no satisfactory single answer to the question of the cultural vibrancy of Vienna 1900. A one-size-fits-all answer risks recasting the city in amber. Indeed, Vienna already offers a popularised, tourist-ready version of fin-de-siècle culture as a repository of avant-garde treasures. The most compelling explanation of the singular richness of Vienna’s cultural legacy is not the lure of empire, nor the utopian melting pot, nor the fruits of a nihilistic Oedipal revolt. It is the notion of the city as polarised and paradoxical – a city in which a number of contradictory things can be true at the same time.

The world of Vienna 1900 was a world in which a quintessentially modernist enterprise was fully realised, in which the present emerged, phoenix-like and future-oriented, out of the immolation of a past that was never fully put to rest. In Vienna it was possible to live in anticipation of the end of the world – in the ‘laboratory of the apocalypse’ – while at the same time creating music, art and literature as prescriptions for the future.

Contemplating Vienna 1900’s relationship with history brings us back to Pierrot, the modern artist floating away from the indignities of the workaday world towards a hazy, distant future-world. But if we imagine him facing backwards, Pierrot in this moment suddenly becomes something more like the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s ‘angel of history’, an image that Benjamin derived from Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus (1920). For Benjamin, the angel of history faces backwards and contemplates the past as an ever-growing pile-up of increasingly catastrophic events, while being blown inexorably into the future by the storm winds of progress. Pierrot, and this angel of history, preside over Vienna at the turn of the century: they symbolise the city’s great cultural flowering, underwritten by unresolved tensions between past and present, even as they presage the end of the fin-de-siècle and anticipate the coming of the Great War.