On visiting the United States, the Tibetan dignitary T T Karma Chophel met with a group of supporters in Utah. He was there to discuss democracy, but his gaze kept travelling out across the high desert to the snowy mountains on the horizon. He thought of yaks and yak-herders, making their endless migrations across a similar landscape in Tibet, and he assumed there must be some US equivalent. ‘Who are your nomads?’ he asked.

The answer to that question depends on how you define a nomad. Some scholars, such as the Russian authority A M Khazanov, maintain that nomads have never existed in North America, with the possible exception of the Navajo, who became semi-nomadic herders after commandeering horses and sheep from Spanish settlers in New Mexico. For these scholars, who specialise in Central Asia and Africa, the word ‘nomad’ can be applied only to pastoral herding tribes who subsist on their livestock. Webster’s dictionary counters with: ‘Any of a people who have no permanent home, but moving about constantly, as in search of pasture.’

Webster’s looser approach calls up a long parade of American wanderers, beginning with the bison-hunting tribes on the Great Plains, and the footloose frontiersmen who opened up the continent to what they were escaping: settlement and civilisation. In the same restless male tradition came the cowboys of the open range, transient loggers and prospectors, railroad hobos, bikers, drifters, Jack London, Jack Kerouac and a multitude of unclassifiable nobodies who shared the same aversion to settling down, who started to itch when they stared at the same set of walls for too long.

Travelling preachers appeared as a response to the fast-moving frontier. Rather than build a church, they’d throw up a tent or preach in a store. Their spiritual descendants are still with us, migrating in motorhomes and pitching ecstatic tent revivals. Americans never stopped hopping freight trains either, and a new generation of tramps, gutter punks, anarchists, troubadours, circus-performers, felons and Bush-Cheney war veterans are now riding the rails, and remolding the hobo life.

Rodeo cowboys travel constantly, often driving 200,000 miles a year to compete in a year-round circuit of events. A proud minority of truck drivers live permanently in their big rigs, and even raise families on the road, homeschooling the children via the internet. Rubber tramps hitchhike aimlessly back and forth across the country, and an estimated 250,000 Americans, most of them retired, are out there roaming full-time in their recreation vehicles (RVs).

‘Moving about constantly, as in search of pasture…’ The description captures something of the American spirit. Wanderlust runs through the country’s history like a virus, mutating across time, reshaping families and communities, opening up territories and opportunities. American literature, music and film all know the call of the road.

‘I got to keep moving… there’s a hellhound on my trail,’ sang the itinerant bluesman Robert Johnson. He sounds like a mournful, disturbed prisoner of his own wanderlust, whereas for Walt Whitman, in his poem ‘Song of the Open Road’ (1856), the journey is freedom and invigoration for the soul. The road is a staple of country and rock songs, both proud anthems and bittersweet ballads. ‘I love you baby, but you gotta understand/When the Lord made me, he made a ramblin’ man,’ sang Hank Williams, who died of an overdose in the back of a baby‑blue Cadillac convertible, on the way to the next show.

The US invented the automobile and the road movie, the motel and the mobile home, the drive-thru restaurant, the trailer park and the freight train as a vehicle for nomadic living. There’s a feeling of comfort and stability that comes from being in motion, especially in the big, wide-open spaces of the West, and a feeling of instability when velocity comes to a standstill, akin to a sailor finding his land legs after a voyage at sea. Trying to define the essence of the US, Gertrude Stein said: ‘conceive a space that is filled with moving.’

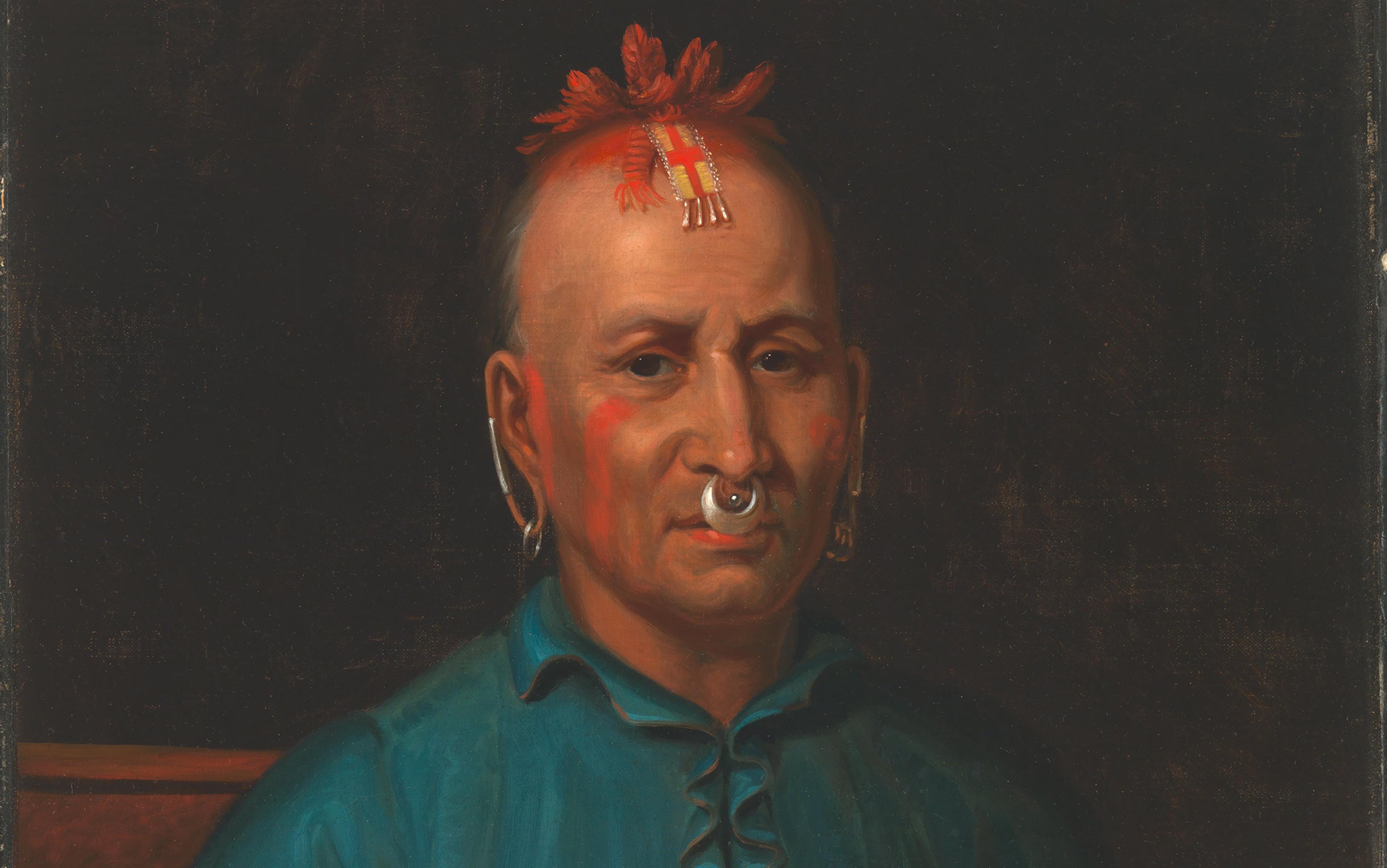

In 1541, while searching for seven fabled cities of gold on the high plains of Texas, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado and his conquistadors noticed strange lines inscribed on the ground, as if people had been deliberately dragging lances. Following these curious markings, they came to a camp of bison-hunting people called Querechos, who lived in hide teepees, and kept bison guts full of blood around their necks, to quench their thirst while travelling between water sources. The drag marks on the ground were from their teepee poles, which they attached to teams of packsaddled dogs when they moved camp. ‘They travel like the Arabs,’ wrote the expedition’s chronicler. This is the first account we have of nomads in North America.

Later Spaniards, settling along the Rio Grande in New Mexico, inadvertently caused a massive upheaval on the plains. Over the course of the 17th century, a revolutionary four-legged technology – the Spanish horse – diffused outward from the Rio Grande and into the Plains tribes. Horses had first evolved on the North American plains, but they had become extinct in the Americas 10,000 years earlier. Now feral herds established themselves on their ancestral grounds, across North America. The Sioux called them ‘holy dogs’.

On horseback, it was possible to travel 100 miles a day, and crucially, to gallop alongside a running bison and shoot an arrow behind its ribs. This was a more effective hunting technique than stalking, fire-surrounds or attempting to drive a herd off a cliff, and many tribes were persuaded to abandon their crops and villages, and begin a new life of following the bison herds on horseback. Populations and life expectancies increased on the protein-rich meat and mineral-rich organs. Hides were exchanged for guns, knives, cooking pots, cloth, beads and other manufactured items brought to them by Anglo, French and Hispanic traders.

‘I have seen nothing that a white man has that is as good as the right to move in the open country’

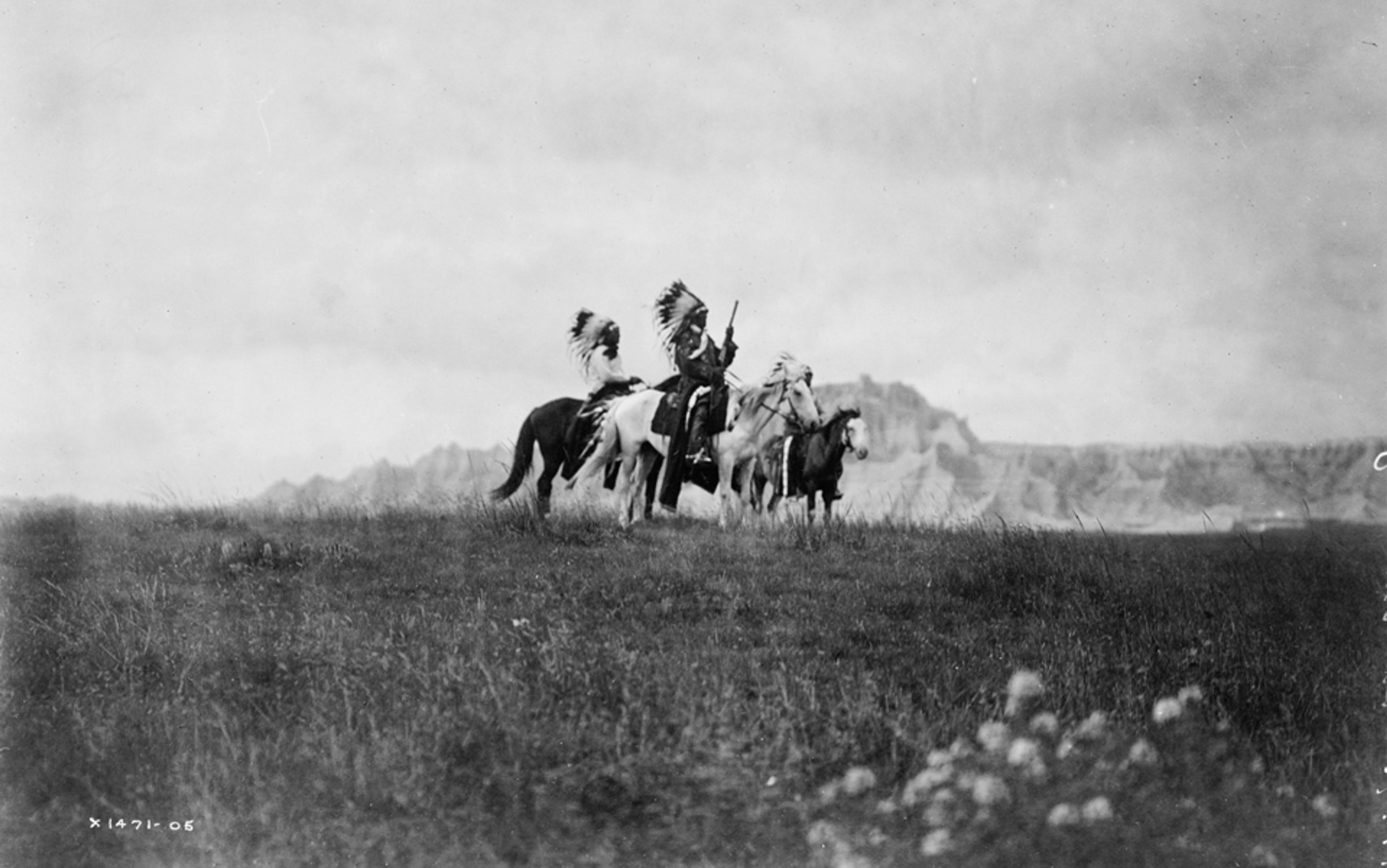

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, a nomadic efflorescence took place on the Great Plains. The now mounted hunter-warriors developed attitudes and prejudices characteristic of pastoral nomads. They equated freedom with open space and mobility, and detested fences, walls, borders and boundaries. They looked down on sedentary farmers and townspeople as inferior, while obtaining grains and goods from them by trading and raiding. They measured wealth by the size of their horse herds, and felt a deep conviction that nomadism, for all its hardships, was the best of all ways to live.

‘The life of white men is slavery,’ said Sitting Bull, the Lakota Sioux chief. ‘They are prisoners in towns or farms. The life my people want is a life of freedom. I have seen nothing that a white man has, houses or railways or clothing or food, that is as good as the right to move in the open country, and live in our fashion.’

‘I was born upon the prairie where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun,’ said the Comanche chief Ten Bears. ‘I was born where there were no enclosures and where everything took a free breath… I want to die there and not within walls.’

The Comanches were the ultimate American horse nomads. A loose confederation of tribal bands, sharing a language and culture, they controlled a vast empire on the southern plains, while raiding deep into Mexico, and trading horses as far north as Saskatchewan. They were the first tribe to fully exploit the potential of the new four-legged technology, the only Native Americans who preferred to fight on horseback. True centaurs, they learned to ride before they could walk properly, and were awkward-looking on foot, moving with a peculiar bow-legged trot.

‘They lay hold of bow and spear; they are cruel and have no mercy. The sound of them is like the roaring of the sea; they ride upon horses, arrayed as a man for battle against you.’

That is the prophet Jeremiah, describing nomadic Scythian raiders in the Bible, but it captures the terror and helplessness that people felt when the Comanches came thundering across the plains, in bison-horn helmets with faces painted black for war, screaming their unearthly war cries, blowing on eagle-bone whistles, loosing a deadly rain of arrows and then following up with lances, war clubs, knives and hatchets. Each Comanche band was a nomadic war machine, fuelled by the energy stored in grass, converted into dried meat and horsepower, and capable of covering 100 miles a day, day after day. Women rode with the warriors to perform camp chores, and had their own techniques for torturing captives.

No enemies could keep up with them, least of all a conventional army, and, as fighters, the Comanches were unmatched for ferocity and effectiveness. By one raid at a time, they drove the Apaches from the plains, blocked the French advance from Louisiana, kicked the Spanish out of Texas, terrorised a huge swath of northern Mexico, and wreaked so much havoc on the Anglo-American frontier that it stalled for 40 years and, in some parts of Texas, reversed eastwards. Europeans hadn’t experienced this brand of violence since the Vikings, or the Mongol hordes.

The Comanches had no concept of ethnic purity, and by the 1830s, at the height of their power, they had absorbed thousands of captives from Mexico, other tribes and the Texas frontier. Their horse herds numbered in the tens of thousands, and they controlled the plains from central Texas north into Kansas and Colorado, from eastern New Mexico well into Oklahoma. Riding across their 250,000-square-mile empire of grassland, with its immense herds of bison, they must have thought it would last forever.

As the Western tribes were mounting up and riding away from their fields, the British were attempting to establish a colonial society in the East. From the beginning, the yawning wilderness at the edge of the Anglo settlements presented a steady threat. The frontier held both American Indians living with unfettered liberty, and the possibility of escape and independence.

The early runaways were mostly slaves and indentured servants, but there was also a steady outflow of misfits, dreamers and adventurers. In 1642, John Winthrop, first governor of the Massachusetts colony, wrote disapprovingly in his journal: ‘many crept out at a broken wall’. Some joined up with Native American groups, or fugitive communities, like the one that survived in the Great Dismal Swamp for 150 years. Others found ways to live in the forest as hunters, trappers, traders, wives, mothers and homesteaders, reinforcing the subversive idea that a freer life was available outside colonial society.

In the early 18th century, a new breed of immigrant started arriving en masse in Pennsylvania, and soon became the dominant vector of restlessness on the frontier. Benjamin Franklin, surveying the tall, brooding, rawboned men and bold-faced women as they came off the boats in Philadelphia, described them as ‘white savages’. They were Protestants from the Ulster colony, but they had been in Ireland only for a few generations. Before that, they had lived an unstable, violent, downtrodden life in the Scottish lowlands and borderlands as tenant farmers, mill hands, cattle drovers and soldiers.

John Knox brought them the flinty creed of Presbyterianism, and in the early 1600s, people in northern England started calling them ‘rednecks’. The term has stuck to their descendants in the US South, but originally it referred to a strip of red cloth that Presbyterian religious dissenters wore around their necks.

Few of these tough characters, who made such an impression on the American imagination, settled down until their health gave out

Once in Pennsylvania, they headed for the Appalachian frontier, where land was cheap or free, and state authority weak. They hacked down trees and built log compounds. They raised pigs and cattle, grew corn and made whiskey from it. They had a tendency to farm a piece of land until the soil was ruined, and then move on. The men learned to hunt and trap, and by constantly depleting the game, they created another reason to keep moving west.

They fell into bloody conflicts with Creeks, Shawnees, Cherokees and other tribes whose lands they were invading, but there were also periods of peaceful coexistence and cultural interchange. Hunting parties met on forest trails and exchanged meat, tobacco and information. White backwoodsmen started dressing in buckskin clothes, moccasins and breech-clouts, and wearing their hair in long braids greased with bear tallow. Some took up the custom of scalping their enemies. Both groups believed strongly in personal freedom, honour and vengeance, loyalty to their family and clan, and they were both highly mobile.

In mid-18th-century Virginia, small groups of frontiersmen started going on extended hunting and exploring trips into what would become Tennessee and Kentucky. People called them Long Hunters, because their trips lasted for six months or more. It was a drifting, rootless, searching life, but still tethered to a base location.

In the 1820s, a group of American frontiersmen cut ties to crops, buildings and European women, launching themselves west as full‑time nomads. They were the beaver-trapping mountain men who blazed trails across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains all the way to the Pacific. Like the western horse tribes, they lived in the saddle, subsisted by hunting, prided themselves as warriors, and stayed on the move, but there were differences. Tribal bands moved as kinship-tied communities with all age groups included. The mountain men were isolated wandering males, who came together to trap beaver. When they wanted female companionship, they would usually break off from the brigade, marry a Native American woman, and hunt, fight and camp with her people.

Most of these nomad trappers were Appalachian-born Scots-Irish, but there were also French Canadians, Mexicans, Europeans and, in Jim Beckwourth, at least one African American. There were maybe 1,000 of them in total, and their era lasted from 1820 to the early 1840s. In less than 30 years, they devastated beaver populations from the Missouri to the Pacific, and essentially trapped themselves out of a trade. The death knell was a switch from beaver-felt to silk hats among fashionable gentleman in Europe.

To find another way of making a living, and staying on the move, the trappers established themselves as traders with the tribes, or guides for the wagon trains heading to Oregon and California. The great Joe Walker, who covered more ground than anybody, went into the horse business. He bought herds from Mexican ranches in California, and drove them more than 1,000 miles to Colorado and Wyoming, and sometimes all the way to Missouri, a round trip of 3,600 miles. Very few of these tough, untamed characters, who made such an impression on the American imagination, attempted to settle down until their eyesight or their health gave out.

The age-old conflict between nomads and the sedentary, which has played out on every continent except Antarctica, with the same eventual result, derives from opposing philosophies of land use. For sedentary societies, land is there to be brought under control and made productive. Otherwise it lies idle and wasted. Civilisation advances in straight lines and rectangles: roads and railroads, ploughed fields and fences, city blocks and four-cornered buildings.

Nomads prefer round edges in their teepees or yurts, and they want land to be wide open and undisturbed. The idea of fencing land into rectangles, of turning it into real estate, is as wrong and unfathomable as fencing the air or the sea. Land is there to be crossed. Grazing is there to be reached. Anything else is in the way.

Nomads and the civilised look at each other with disapproval and misunderstanding. Why would anyone want to wander the wilderness and live in a tent? Why would anyone want to live in a box and obey unnecessary masters?

In the long run, the civilised won because their system generated superior technologies, larger populations, bigger armies, and better systems of knowledge‑retention through the written word. All these advantages were steadily building against the Comanches, but they were undone by a wild‑card factor. The discovery of gold in California set off the biggest internal migration in US history. As the argonauts crossed the Great Plains in 1849, they set loose a rampaging epidemic of cholera among the Cheyenne and the Comanche, who lost half their population that summer including all their headmen and camp leaders. Then came a smallpox epidemic.

With the shrunken bands weakened and traumatised, because their medicine men were powerless against these diseases, white hide‑hunters attacked the Comanche empire, and started wiping out their bison herds. Settlers were again able to advance the frontier. Texas Rangers employed Comanche tactics to make devastating attacks on the Comanche themselves. At Medicine Lodge, Kansas, in 1867, the southern plains tribes in all their gaudy feathered finery met with a few bewhiskered representatives of the US government, backed up by the army. The balance of power had shifted, and the terms were dictated: the tribes had to stop roaming and become farmers on reservations.

‘Why do you ask us to leave the rivers, and the sun, and the wind, and to live in houses?’ asked the aged Comanche chief Ten Bears. ‘We wish only to wander on the prairie until we die.’

In Hollywood, cowboys and Indians are natural enemies. In reality, the violence was between cowboys and settlers who fenced off the open range

The last free band were the Quahadis on the remote high plains of the Texas panhandle. The US Cavalry under Ranald Mackenzie used Tonkawa scouts to trail them to their winter camp in Palo Duro Canyon. All the Quahadis escaped up the canyon walls, but they left behind their teepees and winter supplies, which the cavalry burned, and some 1,500 horses, which Mackenzie ordered his protesting cavalrymen to shoot. For the next eight hours, they shot two horses a minute, and that was the final, brutal nail in the coffin of the Comanche as a free people. Without horses and bison, they had no choice but to submit to the reservation in Oklahoma where their descendants remain to this day. The Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Apache, Navajo, Kiowa, Shoshoni, Blackfeet, Crow and Nez Perce all came to similar ends.

The last nomadic horsemen in the US West were the cowboys of the 1870s and ’80s, who drove herds of Longhorn cattle from south Texas to the railheads in Kansas and Nebraska, and then up to the new ranches and Indian reservations in Montana. They would ride all the way back to Texas and do it again. In Hollywood films, cowboys and Indians are presented as natural enemies. In reality, there was more violence between cowboys and the settlers who started fencing off the open range, making the free movement of men and cattle impossible. Cowboys called the settlers ‘nesters’, and killed them by the dozen in range wars.

Buffalo Bill Cody, a former scout and bison hunter, was the first to recognise that it was safe for nostalgia to set in. His Wild West show featured Sitting Bull and 20 Sioux warriors in mock battles, alongside cowboys, sharpshooters and Arab, Mongol, Turk and Gaucho ‘rough riders’. It was a hit all over the US and Europe. Of course, the bison were gone, the plains fenced, and the American Indians fenced into reservations. But the civilised are always intrigued by nomads, and romanticise them as symbols of freedom and primitive nobility.

In the furnace of summer, the town of Quartzite, Arizona looks forlorn and half-abandoned – a few trailer homes and gas stations huddled alongside the interstate under the pounding desert sun. Come back in January and it’s almost unrecognisable. The population increases from a few hundred to tens of thousands, and motorhomes extend in shimmering ranks into the surrounding desert. Nomadic vendors living in vans and camper trucks set up a huge tented flea market, specialising in gems and minerals, but also selling every piece of unnecessary crap you can possibly imagine, from magic slice-and-dice machines to cactus-shaped toilet-roll holders.

The annual gathering at Quartzite exerts a strange magnetism on America’s modern-day nomadic tribes. There’s not much to see here, and not much to do, and the different tribes take very little interest in each other. Freight-hopping tramps and gutter punks stay under the interstate bridge, getting thoroughly wasted and emerging to beg spare change, and buy more beer. There are separate clusters of road hippies, and wandering New Agers. In a gas station bathroom, I saw a wild-looking freak dying his beard green in the sink. At the adjoining sink, a prim elderly man of the Eisenhower generation was shaving in the mirror. Both of them, I discovered, were full-time nomads.

The iconography of the Old West appears on T‑shirts, and in airbrushed designs on the outsides of RVs

The biggest nomadic group in 21st-century US is undoubtedly the RVing retirees, and specifically the ‘full-timers’ who have sold their houses to buy their motorhomes. You know you’re living in a restless nation when an estimated quarter-million grandparents choose to say goodbye to their families and communities to live on the road. They tend to travel together in herds, moving from campground to RV park, northwards in summer, and south in winter, with brief annual detours to visit the kids and grandkids. In the desert outside Quartzite, you see them park their RVs in a circle like covered wagons, with a central campfire where these genial enthusiasts gather on lawn chairs for cocktails and cheese snacks.

The iconography of the Old West often appears on their T‑shirts, and in airbrushed designs on the outsides of their RVs: running horses with flowing manes, cowboys and Indians, bison, grizzly bears and eagles. RV brand names include Wanderer, Nomad, Sunchaser, Grey Wolf, Palomino, Winnebago, and it’s probably only a matter of time before a retired dentist from Minnesota hits the road in a brand-new Comanche.

When the frontier bumped against the Pacific, the cultural impulse to move on didn’t go away. It got channelled in other directions. The West was tamed and settled, but it’s still a typically nomadic landscape, as Tibet’s Chophel recognised, and the ghosts of nomadic horsemen still ride across it. A creed of nomadic freedom persists here, lurking like a low-grade fever in the shadows of the American dream.

A truck driver once explained it to me like this: ‘Burn down the house and saddle up the horse. Get out of here and keep going.’