‘I’m sure you’ve heard about Sarah Hegazy,’ read the text on my phone. It was 2020; I was tying a red bandana around my face – for both aesthetic and pandemic purposes – en route to a BLM protest in the thick of Manhattan’s June. ‘You’re always checking in on me when something tragic happens in my community. I’d like to extend the same solidarity when something happens in yours. I’m here to talk if you want to.’

That text was how I found out that Hegazy, a 30-year-old Egyptian lesbian activist, had killed herself. I first heard of her in October 2017, when she was jailed by the Egyptian government for flying a rainbow flag at a Mashrou’ Leila concert – an edgy Lebanese rock band known for being openly queer. In Egypt, homosexuality is legally considered a form of debauchery, and in the aftermath of this concert the law was explicitly updated to sanction the promotion of homosexual behaviour in the media with up to three years in prison. For three months after her arrest, Hegazy was tortured at the hands of the Egyptian police, who electrocuted her and encouraged inmates to physically and sexually abuse her. Though she was granted asylum to Canada upon her release, the demons of her trauma followed. She left behind a letter in Arabic that read: ‘To my siblings – I tried to survive and I failed, forgive me. To my friends – the experience was harsh and I am too weak to resist it, forgive me. To the world – you were cruel to a great extent, but I forgive.’

I tried for months not to think about Hegazy. It was easy. Only a thin subsection of my social media feeds dared eulogise her openly. For proper grieving, I had to turn to queer public personalities well outside my social circle: news outlets, international LBTQ+ groups, Arab artists and actors, Mashrou’ Leila’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who wrote a song in her honour, and so forth. But when I didn’t go looking, my Facebook feed quickly and quietly washed her away. There were too many family members lurking in the threads, which meant an unceasing threat of exposure. I knew that many of my young Arab American and Muslim American friends were queer. I knew it through dimly lit gay clubs, through confessional WhatsApp messages. But I also knew from experience that to be queer, Arab, and American is to be constantly under siege: a minority within a minority, doubly marginalised from Western society for being a racialised security threat and from your own Arab community for being an abject, sinful deviant, supposedly ‘invented’ by the Western world. The balancing act sets you up to fail: every space you enter doesn’t want you, or asks that you drop off pieces of your body at the door. Have we always fallen through the cracks like this, I wondered. Was there no room for the queer individual in Arab history? Have people like us simply never belonged?

To navigate life in the closet is to learn, no matter how old you get, never to speak into a microphone or to have your picture taken in places you should not be. It is to curate your clothes before seeing the family, to throw yourself into political activism and community work that is always deliberately (suspiciously) not about you, to learn the delicate gay art of dodging the big questions: the questions posed by your family about your friends, and by your friends about your family. To echo an early pioneer of queer theory, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writing in 1990, ‘closetedness’ is not just a passive silence; it’s a highly specific performance, a costume you stitch together to the exact measurements of your body and background. Except that, in the United States after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, when you publicly put on that performance, you’re also trying to stuff your half-million relatives and their dirty laundry in the closet, too. You’re not keen on showcasing your family’s homophobia, as runaways from white Christian households might be, because your story always runs the risk of feeding something far larger than you: the toxic stereotype of Arab homophobia.

There’s a great shame attached to this stereotype and, by extension, a great shame attached to belonging to the culture it allegedly comes from. Arab societies and governments have been depicted for decades in Western media as rabidly homophobic – a useful, humanitarian stand-in for calling them uncouth, uncivilised, barbaric. ISIS gained far more fame in US popular discourse for throwing gay men off of buildings than for killing thousands upon thousands of Arabs and Muslims in equally gruesome ways across the Middle East. After all, the former reflected a fanatic, Islamic cruelty, while the latter a less deliberate statistic of collateral damage.

Milo Yiannopoulos, a gay, alt-Right has-been whom I had the misfortune of meeting in my undergraduate years, practically delighted in the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting, transmogrifying the deaths of 49 people into soundbites about how the Left had chosen Islam over homosexuals, allowing the inherently savage faith to kill them for the sake of political correctness. The TV talk-show host Bill Maher, in part lamenting with Yiannopoulos over how their disinvitation from the University of California, Berkeley single-handedly spelled doom for the Constitution, made sure to double-down on the ‘facts’: ‘Can you be gay in Gaza?’ ‘They chop [gay] heads off in the square in Mecca.’ ‘It’s not my fault that the part of the world that is most against liberal principles is the Muslim part of the world. There have been studies; we have facts on this.’ Sam Harris, bringing his pop anthropology to bear on global affairs, states often how ‘Islam is the motherlode of bad ideas’, as they ‘keep women and homosexuals immiserated in these cultures’ – much unlike the cultures of the US and Europe.

It is true that anti-LGBTQ+ pogroms can and do take place in the Arab world, but when the tolerant West hears of them, they become part of a larger discussion about reforming a fallen, inhumane people; a discussion buttressed by Pew polls showing widespread homophobia in the Middle East and documentaries about the few queer brothers and sisters who survive in exile to tell their stories. Middle Eastern governments don’t exactly help. One need only look at their responses to Hegazy’s death: an Arabic smear campaign on social media gloating over her suicide, street murals in tribute to her swiftly painted over by municipal authorities in Jordan, death threats directed at those grieving for her lost life.

Erasing Arab homosexuals today feels as though it is tied to an ancient, indigenous history; it feels like a fixture in the gloom of a global past, from which the progressive New Yorkers around me have risen, and within which my family still dwells. As I feverishly reread the text on my phone and marched through Columbia University towards the subway, I felt an uncanny continuity between my present situation and the speech that the then-president of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, gave on this very campus in 2007, in which he declared: ‘in Iran, we don’t have homosexuals like in your country.’

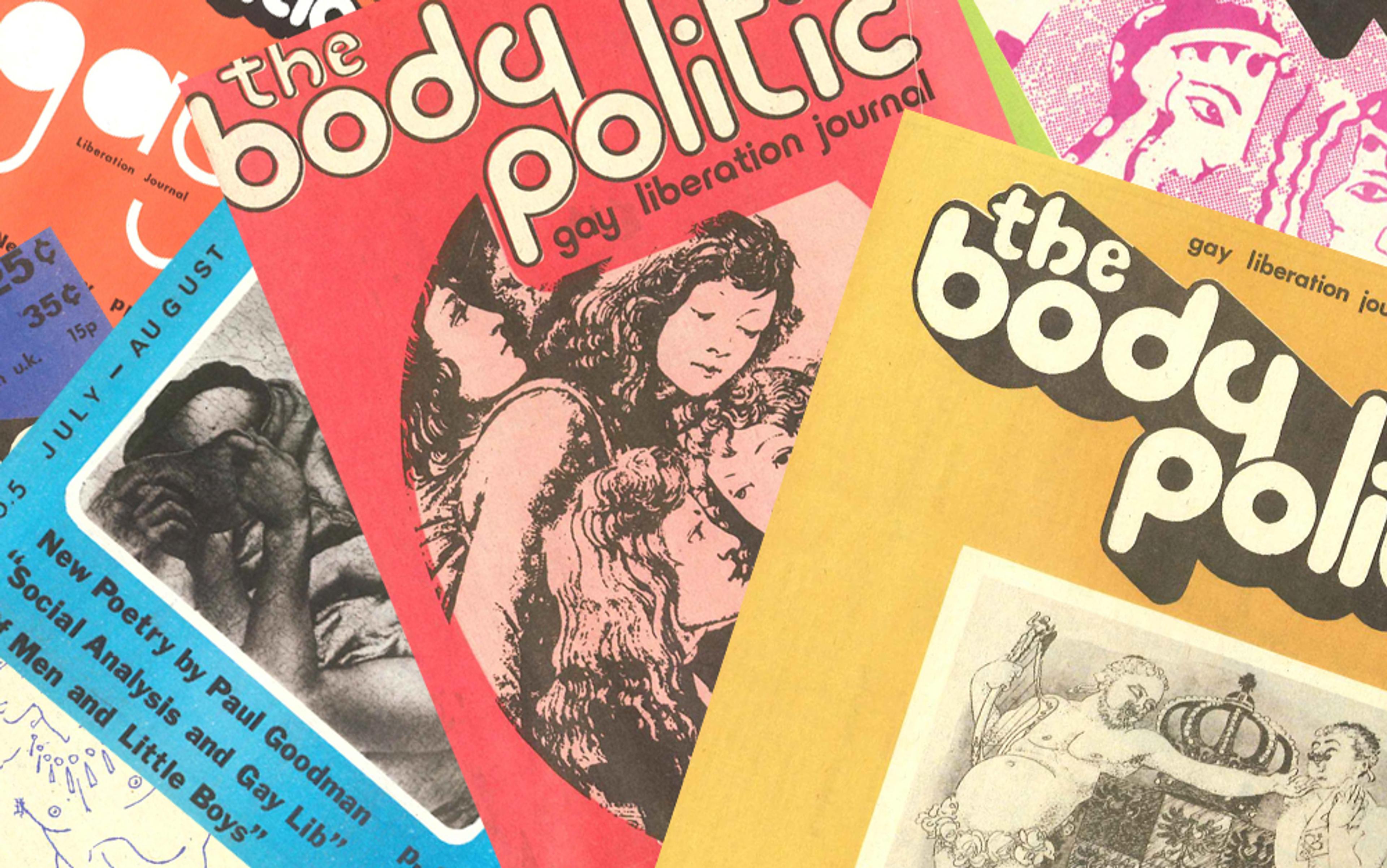

And yet, sometimes, the most iconic and offensive of memes are the ones most ripe for recycling. Unbeknown to Ahmadinejad, and to me when I first fled the closet into Columbia’s campus for my doctorate, this quote gained a second life in the world of postcolonial scholarship. Scholars of the Middle East, such as Khaled El-Rouayheb, Joseph Massad and Pınar İlkkaracan, reappropriated his statement, arguing that homosexuality as a sexual identity was indeed a foreign, Western construct. Few identified as homosexual in Persia, Egypt, North Africa, the Gulf or the Levant before the modern era. Yet many in the Arab world regularly engaged in homoerotic desire and behaviour, and the literary works of the region are testament to homoeroticism’s widespread popularity and acceptability.

The Quran expresses little about homosexuality outside of the story of Lot in Sodom and Gomorra, which is narratively as rich and ambivalent as its Biblical analogue. The Islamic ban, drawn largely from the Prophet’s hadiths, rests primarily on anal penetration (of men or women), and does not seem to have deterred the overwhelming amounts of same-sex desire and intimacy in the region, if literary records are of any indication. Premodern Arab societies condoned alternative sexual acts between the same sex (cunnilingus, fondling, fellatio, making out), and Arab poets frequently wrote homoerotic love poetry up until the modern period. This corpus was perhaps aided by the Islamic tradition’s lack of discomfort with the pleasures of the body. Medieval Islam placed no premium on celibacy, and the Islamic conception of heaven was entirely wrapped up in libidinal pleasures: food, wine and sex with beautiful men and women – a feature that did not go unnoticed by Orientalist scholars in Europe, who deemed it a sign of Islam’s debauched inferiority compared with the pure, disembodied, geometric abstractions of Christ’s Paradise.

Rumi, scrubbed squeaky-secular-clean on Instagram, was known for religious sainthood and homoerotic couplets

Among the most famous of these poets is Abu Nuwas (c756-814 CE), who dazzled the ‘Abbasid court of the Caliph Harun ar-Rashid with songs of his love for wine, girls and boys. He used direct quotations of Quranic verses to seduce young men into sleeping with him, or to describe his drunken, amorous trysts. Abu Nuwas’s poetry includes some stunning passages, such as comparing tufts of pubic hair to the landscape of the Islamic apocalypse, or redirecting his prayer from the Ka’bah – the house of God – to the house of a hot man in the neighbourhood. While Abu Nuwas was frowned upon by more conservative imams of his time, his creative, literary and sexual uses of the Quran were largely viewed as harmless fun, not outrageous blasphemy. No example captures this lax attitude towards art and scripture better than the one relayed in al-Abi’s Nathr al-durr (1030 CE), in which one friend gifts another a set of dildos inscribed with a Quranic verse: ‘Let them enter in peace and security.’ His friend returns them to his door with an updated inscription – another Quranic quip: ‘So we returned it/him to his mother, so that she might be comforted.’ This medieval ‘yo mama’ joke is a far cry from the outrage and mass protests for which the Arab world has become famous.

Nor was Abu Nuwas’s poetry of homoerotic desire exceptional in Middle Eastern literary production and social practice. Scholars of medieval Islam note that the poet merely ‘picked up a theme that “was in the air”’ among his forebears, contemporaries and those he inspired. It is worth noting that Rumi, the 13th-century Sufi mystic whose intense Islamic devotion has been scrubbed squeaky-secular-clean on the Instagram captions of your friends, was known for both his religious sainthood and his homoerotic couplets.

The poetic archive for female same-sex desire is far smaller, but some incidents are noteworthy. In the generation immediately after Abu Nuwas, a friendly argument was recorded in the Kitab al-Aghani between the Caliph al-Ma’mun and a female court-singer named Bathal over whether penetrative sex with a man was more or less pleasurable for women than lesbian sex (Bathal insisted on the latter). The historian Samar Habib calls this low-stakes banter ‘a small room in which we glimpse … the relations between legislative authority (in the figure of the Ma’mun) and those who are its deviant subjects’, relations that were far less rigid than we are now taught to expect. This attitude towards homoerotic verse and behaviour continued well past the Abbasid era in which Abu Nuwas and Bathal lived. The historian Khaled El-Rouayheb has shown that the early Ottoman period (1519-1798) was replete with casual and sympathetic references to homosexual love and heartbreak, with little to no scandal or outcry.

Fast-forward to the modern world, and conditions for homoerotic love take a turn for the worse. Once more, the reception of Abu Nuwas’s poetry is a perfect case study for the dramatic shift that took place in the 20th century: though widely quoted and celebrated throughout most of Islamic history, Abu Nuwas became the focus of a whirlwind of anxious commentaries and psychoanalytic biographies by Arab scholars in the modern period. In what the cultural critic Joseph Massad calls a ‘civilisational anxiety’, Arab intellectuals of the 1900s feverishly tried to reconcile how this poet could be so central to the history of Arabic literature while also partaking in (supposedly uncivilised, unnatural, perverse) homoeroticism. Even worse, Abu Nuwas flaunted his decadent sins in the public eye and among the high society of his time, indicating that public opinion – ranging from the Caliph and his judges at the top to the bards and traders on the ground – was not fully disapproving of sexually ‘deviant’ practices. How could Abu Nuwas and poets like him – let alone the Caliphs they drank with and sang to! – belong to the supposedly virtuous and sexually pure Arab and Islamic past?

The pearl-clutching, prudish moral conclusions many of these intellectuals reached to resolve this tension were oddly Victorian. They marked Abu Nuwas’s time and the centuries that followed as periods of Islamic ‘degeneracy’ and ‘decline’ that explained why the Middle East had fallen under the control of the West. Islam needed a Reformation, it seemed, a Reformation that would purge its permissiveness and theological flexibility. That would restore its former glory and establish rigid moral codes. But where did this notion of degeneracy and decline come from in the first place? How did this ‘Reformation’ become a cultural fixation?

The answer is complex, but colonisation is undeniably a part of it. Precolonial European travellers in Ottoman lands gawked at the popular tolerance of homosexuality, leveraging new concepts of an ‘unnatural’ and degenerate Oriental sexuality desperately in need of Christian reform. Conversely, Arab travellers through Europe in the 1800s noticed that there was a widespread intolerance of homosexual behaviour. The Egyptian scholar Rifa’ah al-Tahtawi (1801-73) noted that European Orientalists translating Arabic poetry often transformed the romantic or elegiac same-sex relationships it depicted into heterosexual relations, swapping the names of male beloveds for female ones. This is reminiscent of the treatment that European translators of this same period also gave to the now lesbian icon, Sappho: perceiving the homosexuality of ancient Greece as tarnishing their otherwise supreme cultural (and Western) Enlightenment, the lesbianism was written out.

As Western intellectuals and Christian missionaries advanced into the Arab world in the 19th and early 20th centuries, condemnation of same-sex behaviour became more overt. In the unprecedented age of mass printing and translations from English, French and German into Arabic, Arab intellectuals in elite social stratas internalised these European racist and homophobic assumptions about their ‘regressive’ conditions. Eventually, Arab inferiority and decline, and the inability of the Arab native to govern himself or his desires, would come to be cited as reason for the English and French colonial invasions of many Arab nations, from the conquest of Algeria in 1830 to Egypt in 1882 and Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine and Iraq in the 1910s and ’20s. In a sense, the explanations of Arab decline came true: Europeans predicted that the moral decay and social permissiveness of these Islamic nations would lead to their total political and economic paralysis, and then brought about that paralysis themselves, coaxing the dark prophecy to fruition.

‘Homosexuality’ became a foreign element, branded as a rare aberration, the result of wealth and boredom

In their zeal for reform, the British and French introduced laws criminalising homosexual behaviour – laws that were foreign to those they governed in the name of ‘civilisation’. Today, of the more than 70 countries that criminalise homosexual behaviour, more than half are former British colonies. Much the same can be said about the Gulf States, now used as shorthand for oil and Islamic fundamentalism, in which the British Empire enjoyed what James Onley called an ‘informal empire’ between 1820 and 1971. This was not restricted to the Middle East, either. As the historian Shafiqa Ahmadi argues: ‘Victorian morality and negative views on sex largely influenced the penal codes in nations where Islam was practised, like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, inherited from the British and other colonial powers.’ After their independence, Asian nations such as India, the Maldives, Burma and Nepal maintained anti-sodomy laws reminiscent of British anti-buggery legislation.

In the colonial and postcolonial Arab world, Victorian morality did not merely function as a legal gloss: it trickled into the topsoil of cultural identity. To resist the Western imperialists who justified their presence through claims to superior culture, one had to construct an Arab and Islamic civilisation on equal terms. The present inferiority of the Middle East, an assumption lifted wholesale from European scholarship and governance, had to be explained through the supposed influx of ‘foreign elements’ into Arabic and Islamic heritage. ‘Homosexuality’ became one of these foreign elements, and was branded as a rare aberration, the result of wealth and boredom or, most commonly, an imported Persianate parasite. The notion of this ‘gay import’ was fermented in the 1950s in the heyday of Arab nationalism, reacting to the need for national ‘Arabness’ to defend itself from real foreign interference during the Cold War, and the alliance of the Iranian Shah with Israel at the time.

Worse than the Persianate influence was the supposedly European one. Arab nationalists, in trying to expel the foreign colonisers, justified the expulsion of all aspects of life attributed to them – homosexuality included. Sayyid Qutb (1906-66), one of the key thinkers of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, wrote ‘anthropological’ assessments of American sexuality – meaning that he watched a lot of Hollywood. He recoiled in horror at the primitive decadence of ‘slutty’ American women and Western tolerance for deviant gays, the latter of which, he claimed, was ‘entirely foreign’ to the Arab world. This is supremely ironic, of course. The US of the 1940s and ’50s was a terrible place to be queer, as news media raised the alarm on the potential treachery of ‘faggots’: as Massad notes , the rise of ‘US anti-Communism broadened to target homosexuals, who as early as 1947 began to be purged from government jobs.’

In reality, Qutb and the 1980s ‘Islamic’ fundamentalism that came after him cannot be said to have used Shariah law to attack the West, but rather used institutionalised Western homophobia to attack the sexual diversity of their own societies. In some ways, one can rebuke the likes of Sam Harris, Thomas Friedman and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who demand ‘moderate reforms’ or an ‘Islamic Reformation’ on a par with the Protestant one, in order for the Arabs to become more properly civilised, by saying that Islam and Islamic culture has already undergone a reformation – a colonial, Victorian reformation – and that this is precisely the problem. Once more, the harshest condemnations often came down on Abu Nuwas, just as the loudest celebrations were made of him on the same soil in a bygone era. As recently as 2001, under pressure from Islamic fundamentalists, the Egyptian Ministry of Culture ordered the burning of 6,000 volumes of his poetry.

Meanwhile, the modern West likes to think of itself as having evolved past its hatred for the LGBTQ+ community – so far, in fact, that it would like to civilise the savages in the Middle East all over again. Sexual minorities are weaponised against the vulnerable and marginalised Brown communities that they come from; queer issues are routinely pitted against racial and international justice. The gender theorist Judith Butler offers the example of the Dutch Civic Integration Examination. In 2006, Dutch immigrants were forced to take an exam that included the ‘mandatory viewing of images of two gay men kissing as a way to test their “tolerance” and, hence, capacity to assimilate to Dutch liberalism.’ Butler asks: ‘Do I want this test administered in my name [as a non-heterosexual person] and for my benefit? Do I want the state to take up its defence of my sexual freedom in an effort to restrict immigration on racist grounds?’

It’s a question we all need to ask. What does it mean for us non-conforming peoples to become a new tool to harass religious minorities, to designate other precarious people as ‘not Dutch enough’ (as if a white Dutchman would ever be ejected upon not passing such a tolerance test), or to serve as the justification for someone’s deportation back to a dystopia they narrowly fled? Do I want to be placed on a pedestal at the price of pushing my relatives into the sea?

The value that the West now places on LGBTQ+ life is itself both necessary and disturbing: necessary because these are lives worth saving; disturbing because these lives are seen as more valuable than other equally desperate people begging at the border. As late as 1990, LGBTQ+ individuals were branded as ‘psychopathic personalities’ and so barred from entering the US but, now that this law has been repealed, asylum-seekers must instead ‘prove’ that they are gay enough to qualify for human rights. Up until the early 2000s, proving one’s homosexuality required graphic details of appropriately gay sexual experiences and physical conformity with a strict femboy/dyke stereotype. Not being gay enough meant being turned back.

The same pattern is replicated in the current refugee crisis. I have met several Syrian men and women who suppressed or misrepresented some parts of their sexuality to escape the purgatorial camps, sinking rafts and barrel bombs. The notion that a human life can hang in the balance of a haircut or the right kind of drunken blowjob is not what we think when we think of ‘rights’ or ‘asylum’ – nor should it be. As we saw in the Pride Month of June, and its blinding onslaught of rainbow, LGBTQ+ branding is a substitute for LGBTQ+ safety. A similar horror seizes the Arab queer upon encountering ads sponsored by the US military, exalting the progressive acceptance of all orientations into the drone-directing fold. Congratulations: we can now have queers bombing other queers.

What history is ultimately good for is ridding us of our crippling sense of shame

All these considerations – the delightfully decadent past, the inhospitable present, the complicated ethical allegiances of the future – leave the Arab and Arab American queer community in a very confounding world. Many of us are both straight-passing enough to be victimised as Arabs or Muslims and queer-seeming enough to be ostracised from those same groups. What is the point of knowing about Abu Nuwas if today our safest havens are clubs and college classrooms in Western cities? Surely, the purpose of history is not to refine our finger-pointing. While Right-wing pundits might derive joy from firmly anchoring barbarism in the Middle East, it is equally false (not to mention politically useless) to anchor it in the West. Not everything is colonialism’s fault and, moreover, it does not exactly help our day-to-day lives to determine if it is. Nor should history be an excuse to reductively sanitise and glorify the past. After all, this is not a nostalgic essay – it is good to know that the Abbasids were more gay-friendly than the modern Arab average, but none of us would like a return to the Caliphate (some folks tried that recently, albeit with bad taste). So where does one go from here?

Butler follows up her Dutch immigration example by prescribing a kind of tense coexistence: that though religious and sexual minorities might have their antagonisms, ‘modes of separateness’ can coincide with ‘modes of belonging’. In other words, the solution she pushes us towards is uncomfortable cohabitation. Groups of devout Sunnis and sex-club enthusiasts sharing the same city, bristling against one another at times, but banding together when it really matters: to lobby their local governments about reducing traffic, for example, or to expand their urban parks. Basically, these communities should not be splintered off and segregated from the top down through racist criminal and border policing, but rather be forced to deal with one another and form unexpected alliances by being at close quarters. It is an unsexy answer, as municipal politics always is, and, while there is something to it, I’m not sure it does very much for the individual person trying to cope with a thorny reality.

I find it more helpful to think of history along the lines of the novelist Zadie Smith: what it is ultimately good for is ridding us of our crippling sense of shame. There is not necessarily a prescriptive use to history. The old adage about those who do not learn their history being ‘doomed to repeat it’ is not always accurate: I am sure many sexual minorities wish that simply remaining ignorant about homosexuality’s history in Islamic culture would cause the Middle East to start writing sappy gay poetry again. What history can do is ease one’s embarrassment on the world stage. Smith recounts her thoughts as a Black, British Jamaican child, growing up with the English education system that glossed over the empire’s role in the global enslavement of Black people and the impoverishment of the planet. Upon encountering her people’s material poverty, she asked herself the forbidden question: ‘Why did “my people” submit to this treatment? … Why were there 6 million slaves?’ Or more simply, the shame of a small child asking: ‘What’s wrong with my family?’ Understanding the history of why the world looks the way it does can rid you of that shame. History can be used to push against what has congealed in the present: not just homophobia, but the notion that homophobia is ‘ours’, is how we are, is something ‘our’ kind of people have to apologise for. Reviewing the history of colonialism is not about assigning blame to the modern West – it is about removing blame from the shoulders of Arab families stigmatised for an intolerance they did not create.

History does not offer us much optimism because things can just as easily get worse as they can get better. But it can offer us a sense of much-needed surprise. Although we are meant to consider ourselves today as living at the pinnacle of modern progress and human civilisation, the past is actually not uniformly worse or better than the present. The past was just different; uncategorisable, unexpected. It offers us a sense of extended possibility; the possibility of being unstuck from what feels like the eternal damnation of seeing queer people such as Sarah Hegazy find no choice but to die. This is not to say history could have saved her, or could have saved anybody; it is not a cure for PTSD. Grieving her is not a teachable moment.

But it means that the pendulum can swing back in our direction, too. History is not really about finding the real culprits, the Arabs, the Brits, the imams, the empire. It is about using the space that is freed up by removing shame from the equation entirely – space for something more productive, such as agitating for our vision of a future. And that vision is not so far-fetched when you have done your reading. The first anniversary of Hegazy’s death was on 14 June 2021. Just as Egypt once freely sang the couplets of Abu Nuwas, let us sing today the queer punk-rock of Mashrou’ Leila. And let us say that we are not actually calling for a reformation – we are going back to our roots.