The ideal of equality has broad appeal – most people in liberal democratic societies claim to endorse the principle that we should be equal before the law and that people should be treated with equal respect. Even defenders of the free market often put their case in terms of equal property rights. Yet we live in a world where the gap between the haves and have-nots is growing, racism and discrimination are on the rise, and even basic democratic and legal rights are in jeopardy.

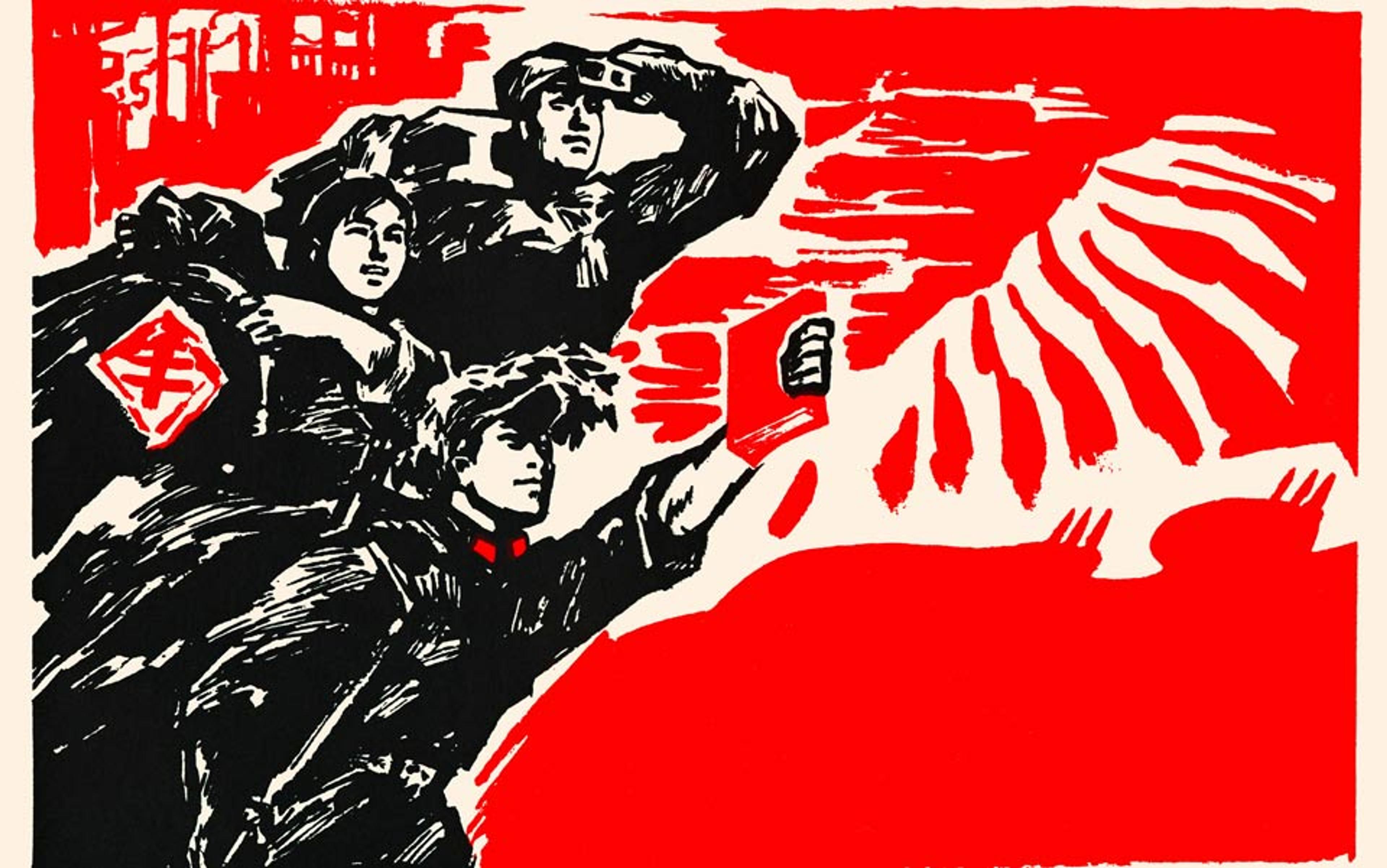

Historically, the socialist tradition, particularly the thought of Karl Marx, has been a source of inspiration for the call for greater equality. Socialist ideas sparked revolution in many parts of the world and, in many countries where capitalism persisted, socialist ideas about people’s equal entitlement to have their needs met prompted radical reform, in the form of social welfare guarantees such as socialised medicine, unemployment benefits and pensions.

Today, however, the Left faces a sobering philosophical landscape where socialism is eclipsed by liberalism in egalitarian thought. This is not just because of socialism’s declining fortunes in the world with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of Right-wing populist parties and movements. Since the publication of John Rawls’s canonical book A Theory of Justice (1971), the liberal tradition has set the terms for debate about distributive justice among Anglo-American political philosophers. And Marx’s socialist slogan ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!’ – though stirring – remains just a slogan.

Iris Murdoch pictured in 1966. Photo by Horst Tappe/Hulton Archive/Getty

In 1958, the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch complained about the paucity of progressive thought in the Britain of her day in the essay ‘A House of Theory’, which appeared in a collection of radical political writings. Murdoch, along with her fellow contributors, bemoaned the decline of socialist conviction, the loss of energy and vision on the Left. Murdoch’s essay is largely forgotten among political philosophers, but her lament is no less relevant today. Recent trends in liberal egalitarian political philosophy, for all their influence in the West, have fallen short of adequately defending the ideal of equality, showing a lack of imagination in just the way noted by Murdoch. Furthermore, the influence of liberalism, in political philosophy, and in Western capitalist societies, is such that thinkers on the Left too often assume the necessity of these parameters.

In this essay I take up Murdoch’s call for a radical vision of egalitarianism as furthering equality of human flourishing, or wellbeing. I contend this will enable us to better understand and further what is at stake in the ideal of equality.

It is often remarked that, for most of the 20th century, political theory languished in the shadow of scientistic views that had dominated philosophy as a whole. Logical positivism insisted on the strict delineation of conceptual from empirical enquiry, matters of fact from matters of value, themes that lingered in the succeeding school of ordinary language philosophy. Murdoch blamed the dominance of a sterile logical analysis for contributing to the lack of vision and creativity in progressive thought. Whereas moral philosophy, as Murdoch put it, ‘survived by the skin of its teeth’, turning itself into a meta-discipline concerned with understanding concepts, political philosophy ‘almost perished’. The intrinsically controversial nature of prescriptions about justice, equality and liberty was replaced with an analysis of how words were used; gone was the ancient Greeks’ idea of political philosophy as reasoned enquiry into how we ought to live in common.

The diminished role of political philosophy as a normative exercise doubtless reflected not just an empiricist outlook in philosophy but also a smug acceptance of the empirically given, that is, the ascription of an automatic legitimacy to the liberal institutions of capitalist democracies in the postwar period. This dogmatism about politics in the liberal West that came with the Cold War helps explain why political philosophy was in a state of stagnation. As Murdoch put it, with the achievement of the welfare state, people were no longer motivated to ‘call up moral visions’, to ‘lift their eyes to the hills’.

Rawls’s defence of equality falls far short of the imaginative enterprise sought by Murdoch

Complacency was jolted in the US, however, in the 1960s, when the postwar liberal consensus came under attack from both a new Left galvanised by the student movement, and a new Right that emerged from conservative critiques of welfare economics. Political philosophy was reborn with Rawls’s canonical work, providing that ‘systematic political theorising’, the absence of which Murdoch had noted more than a decade before. I propose, however, that perhaps it was a pyrrhic victory.

Rawls’s theory gave priority to classical fundamental liberties yet married them with redistributive principles to mitigate disadvantage. In so doing, Rawls provided a robust justification for the liberal welfare states of democratic capitalist societies throughout the West, and his profound influence, in both theory and practice, continues to this day. Rawls’s defence of equality in the context of capitalist market societies, however, was achieved at the cost of scaling back both the scope and ideals of egalitarian thought, falling far short of the imaginative enterprise sought by Murdoch.

For Murdoch, the desire for human equality was a crucial source of the ‘moral energy’ of past socialist movements. Since Rawls, however, although their views are dubbed ‘egalitarian’, few liberal philosophers call for socioeconomic equality per se. Rawls’s Theory of Justice proposes that, if we reasoned about justice in a thought experiment where we do not know our talents, race or class, we would opt for a ‘difference principle’ where inequalities are permitted, but only if they benefit the worst-off. If it turns out, for example, that human motivations are such that incentives are required for the talented to be productive, then so be it: we should pay the talented more than the rest of us. Better, says Rawls, to have a larger aggregate of resources with which to improve the situation of the worst-off – a bigger though unequally divided pie – than equality per se.

In The Morality of Freedom (1986), the legal philosopher Joseph Raz complained that equality is an empty concept, susceptible to justifying the absurdity of ‘levelling down’. Levelling down means that, given a commitment to strict equality, widespread poverty is preferred over unequal wealth, even if everyone, including the less advantaged, would be better off under an unequal distribution. Raz’s objection captured a growing sense that, unless one could adduce evidence that, in fact, an unequal distribution would impose hardship on the worst-off, equality per se should not be our goal.

Accordingly, many liberals went even further than Rawls, taking the view that the question of relative shares is irrelevant; what matters is only if people have a sufficiency. Even those who agree that it matters how much one person has, compared with another, tend to dispense with equality per se. In Ronald Dworkin’s theory, social insurance is needed to remedy the inegalitarian effects of luck and opportunity, but there will be inequality; it would be absurd, Dworkin says in Sovereign Virtue (2000), to exact the very high taxes required to insure against the likelihood of not being a movie star. In general, liberal egalitarians either start with equality but depart from it, or assume inequality and aspire to mitigate it. All in all, the principle of equal distribution of resources is largely abandoned.

Rawls scaled back egalitarianism in another respect, taking the view that principles of justice should concern the distribution of the means to one’s pursuits, without taking an interest in the pursuits themselves. Both liberal political theory and the liberal state should be ‘neutral’ about people’s plans of life, Rawls argued in Political Liberalism (1993). This aversion to invoking considerations about wellbeing is widely shared among liberal philosophers. Indeed, in A Matter of Principle (1985), Dworkin had ventured an egalitarian rationale for political neutrality: the ‘television-watching, beer-drinking’ citizen’s plan of life should not count any less than the plans of life of the intellectual or the aesthete. Market mechanisms, not normally thought to promote equality, were commended by egalitarians for their indifference to people’s choices, their even-handedness towards all plans of life.

The ‘natural lottery’ captures how people’s talents and temperaments are unequally but arbitrarily allocated

Liberal egalitarians’ resistance to incorporating ideas of living well in their philosophical doctrines doubtless reflected an understandable unease with the repressive and intolerant strains in US political culture, a fear that bigoted moral views would be enforced on others. The idea that one’s life goes best if led from ‘the inside’, according to one’s own plans and goals, had much to do with the influences on the outside in the US – where ideas of the good life are derived from convictions about the right to bear arms, not being ‘un-American’, the denial of women’s bodily autonomy, bible-thumping, and repressive notions of salvation. But the result has been an inability to confront the fundamental question of the inequalities in how people live, what Murdoch eloquently called ‘the power to imagine what we know’.

Rawls’s ideas about individual choice generated further constraints on egalitarian thought. He stressed that people were responsible for their plans of life and the extent to which fulfilment might come with one plan rather than another. At the same time, Rawls coined the evocative expression the ‘natural lottery’ to capture how people’s talents and temperaments are unequally but arbitrarily allocated and thus not the basis for unequal reward.

His focus on the worst-off was a no-strings-attached view, but liberal egalitarians since Rawls have argued that a theory of justice should focus on his theme of arbitrariness and responsibility more precisely. Dworkin proposed that inequalities that result from the unpredictable vagaries of ‘brute luck’ are properly the object of egalitarian policy, but inequalities that are due to ‘option luck’, that is, due to people’s choices, are not owed compensation. A community may offer humanitarian assistance to the hapless squanderers of resources, but it is not required to by justice. At issue, Dworkin says, is a principle of responsibility; we cannot expect to be protected from failure if we risk or make poor use of our resources.

‘Luck egalitarianism’, as this concession to inequalities came to be called, proceeded to dominate egalitarian thought, even drawing the approval, surprisingly, of thinkers from the Left, like G A Cohen, who in 1989 congratulated Dworkin for ‘the considerable service’ he had performed for egalitarianism in incorporating ideas ‘of choice and responsibility’ from ‘the arsenal of the anti-egalitarian right’. Such a rationale is a far cry from the ‘general revolt against convention’ that Murdoch celebrated about socialist movements in the past.

True, Left-wing luck egalitarians stress the great extent of brute bad luck, to argue that their position actually dictates significant redistribution of wealth. Cohen went so far as to propose that the arena of luck included affinity for expensive pursuits. For example, playing a sport that involves costly equipment (think of the misfortune of being a Canadian hockey parent) should not be considered a matter of mere choice. Moreover, in the case of global justice, factors like climate are examples of bad brute luck meriting significant redistribution (see, for example, its application to global justice by the philosopher Kok-Chor Tan).

Yet for all these generous interpretations on the part of Left-wing interpreters, it remained that luck egalitarianism, in one form or another, tended to dominate egalitarian thought. Even the doctrine’s critics, such as Elizabeth Anderson, agreed that a satisfactory egalitarian theory must dispense with ideas of receiving goods without an obligation to produce them. Context is again relevant. The luck-egalitarian creed was born in the ‘New Right’ era of the 1980s and ’90s, which saw the election, with working-class support, of the Right-wing leaders Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, and the ensuing move to the Right of social-democratic parties like the Labour Party in Britain, a move that in the years since has arguably been compounded rather than reversed. Perhaps it seemed a good strategy to exclude from one’s doctrine of equality, even if only conceptually, what conservatives called ‘welfare bums’, people whose poverty was deemed to be in some sense their fault. What Murdoch sardonically called the ‘dangerous region of “mushy” thinking’, in all its senses, could then be averted.

Though it made an important contribution to understanding the injustice of economic disadvantage, I believe liberal philosophy clipped the wings of the egalitarian ideal. First, let’s return to our original question of equality in the allocation of goods. It is interesting to note that Marx, too, rejected strict equality in distribution, but for reasons unlike those of Rawls. Given the diversity of human needs, Marx argued that equal shares would simply aggravate inequality. Indeed, giving the brawny rugby player the same diet as his diminutive grandmother affords them equal shares, but leaves them unequally fed. The idea that true equality involves differential treatment, however, was no mere ‘sufficientarian’ or ‘prioritarian’ position, in the words of Pablo Gilabert and Richard Arneson, respectively. Equal wellbeing is, after all, the ultimate goal in the socialist picture. In calling for a nuanced approach to the problem of economic disparities, Marx was a thoroughgoing egalitarian where liberal egalitarians are not.

Rawls permits departures from equality on pragmatic, not moral, grounds, justified only insofar as they benefit the worst-off. But why should there be any such departures? At a time when the gap between rich and poor is especially yawning, the incentive argument seems particularly hollow. Indeed, Left-wing egalitarians like Cohen contend that, when the ‘high-flyers’ insist that their productivity necessitates they keep a greater share to themselves, they are betraying bad faith with the egalitarian project, indeed engaging in a kind of blackmail; this hardly counts as a principle of justice. Cohen invokes the feminist slogan ‘the personal is political’ – how justice requires that individuals be committed to its ideals in their everyday lives. As he evocatively put it: ‘If you’re an egalitarian, how come you’re so rich?’

Incentive arguments take for granted that narrowly selfish, monetary interests will always be the principal motivation for human beings. This is a long way from the idea of ‘true community life’, as Murdoch put it, that was inherent in the ideal of equality for the Left. Liberal preoccupations with restricting eligibility for egalitarian redress conjure up odious Victorian notions of the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor. But what about the undeserving rich, those who are lucky enough to inherit wealth? Moral justification cannot be mustered for cases of good brute luck enriching people, let alone cases where the rich owe their wealth to exploitative behaviour. And think of the many ways in which governments subsidise capitalist companies; there are ‘corporate welfare bums’ as identified by David Lewis, a Canadian social-democratic politician active in the 1970s. It seems odd indeed that egalitarian attention is focused on the so-called irresponsible behaviour of the poor.

No one denies or even moralises cancer treatment to the lifelong smoker, or knee surgery to the extreme skier

In any case, people may be making imprudent decisions ‘according to their ability’, as Marx’s communist principle put it. If we reflect on the choices we have made in our lives, be they wise or foolish, and the conditions under which we made them, it is difficult to isolate the effects of luck. Parents, friends and mentors, education, locale and situation all influence our choices; indeed, capacity to choose is arguably itself unchosen. (This was Rawls’s thinking in his notion of the natural lottery: ‘Even the willingness to make an effort, to try, and so to be deserving in the ordinary sense is itself dependent on happy family and social circumstances’, while Keith Dowding invokes ‘relative parenting pushiness’ as an example that tracks cultures, but also diversity within cultures, that suggest it’s ‘hard to disentangle luck and responsibility’.) Questions of responsibility are hard to determine in light of what we know about the impact of social class, the culture of the chronically poor, the challenges of initiative and enterprise under straightened circumstances.

The school of luck egalitarianism has been responsive to criticism, elaborating further the idea of insurance provisions to protect people from the consequences of their bad choices. Yet such remedies raise the question of why choice is being adduced in the first place, even as a conceptual possibility. The most cash-strapped, inadequate systems of socialised medicine in capitalist democracies do not attach conditions of prudence for the distribution of healthcare; no one denies, triages or even moralises cancer treatment to the lifelong smoker, or knee surgery to the extreme skier.

Instead of thinking about accounting for disadvantages in a ledger of responsibility or haplessness, the socialist R H Tawney wrote in the 1930s that the equal society should not get mired in the ‘details of the counting-house’. Murdoch’s remark that ‘we have not mended our society since its mutilation by 19th-century industrialism’ is an apt reflection on the mean-spirited attitude threatened by luck egalitarianism, which seems a far cry from socialist ideals of solidarity, trust and generosity.

The socialist tradition appreciates the extent of the disadvantages of social class, how they limit the options available to a person, who must sacrifice long-term opportunities for the sake of immediate material needs, whose family background renders some opportunities unimaginable, who is discouraged by teachers who underestimate their abilities. It seems a tragic irony that contemporary liberal theories of egalitarianism seem to embrace not Marx’s communist ideal of distribution according to need but Stalin’s repurposed maxim that ‘he who does not work, neither shall he eat.’

The equal community is best guided instead by a ‘social ethos’, where people undertake a personal commitment to the egalitarian project, contributing as best they can, and displaying a generous attitude to their fellows. In Why Not Socialism? (2009), Cohen illustrates this with the delightful example of a camping trip where there is ‘collective property and planned mutual giving’. The campers’ flourishing requires that all share the fruits of their prudence, capacity and luck, be it knowhow about the best fishing hole, or equipment when it comes to the hapless unprepared camper. (Of course, this ideal is at odds with Cohen’s luck egalitarian view, which Cohen admitted he could not resolve.) I will not tackle further the problems of luck egalitarianism here; but my own human flourishing approach in Equality Renewed (2017) eschews the distinction between option and brute luck as a criterion for the remedy of disadvantage.

This brings us to the question of the place of human wellbeing in our understanding of equality. We saw how Rawls and his colleagues reduced the scope of equality in that respect, too. Indeed, liberals like Rawls and Dworkin could be said to promote a kind of juridicalisation of political thought, where legalistic notions of neutrality and personal responsibility barred questions of community and substantive value. In the face of the persisting, profound inequalities of capitalist societies today, it is worth considering a more ambitious vision that better captures what’s at stake when people have unequal income, and that can engage ordinary people in their political commitments.

Liberal squeamishness about what’s been dubbed a ‘perfectionist’ creed is understandable given, as already noted, intolerant conceptions of the good rampant in US society, but also given historic exemplars like Plato and Friedrich Nietzsche, who contended that the nature of the good was grasped only by the few. In its pursuit of equality, the socialist tradition, in contrast, takes a broad view of the reach and scope of human wellbeing, focusing on goods and resources, respect and equal participation, but also non-alienated, fulfilling and valuable pursuits for all.

The socialist critique of capitalism takes seriously not just impoverishment, but the impoverished lives that people are forced to live under conditions of inequality. Marx’s case against capitalism centred on how material deprivation resulted in the affront to the ‘nobility of man’, how alienating work makes people ‘stupid and one-sided’ and allows for the ‘overturning of individualities’. The ideal of communism involved creative labour and community as well as the satisfaction of basic needs. Murdoch remarked decades ago that, for ordinary people, ‘work has become less unpleasant without becoming more significant’. That is still true today. The Victorian aesthete William Morris came to his socialist convictions in his analysis of how capitalism condemned people to lives of ugliness – in their work, but also in their homes, relationships and communities. Socialism, in contrast would aspire to all living well in surroundings conducive to human flourishing.

It was not just Marxists who put human flourishing at the centre of their political aims. Living well undergirds the original rationale for the welfare state, as evident in the British economist William Beveridge’s concern that problems of ‘idleness’ and ‘squalor’ be addressed by postwar social policy. His Labour colleague, the political theorist Harold Laski, also purported that the remedy of inequality would involve a ‘high level of general culture’ since civilisation is ‘a common enterprise which is the concern of all’, enabling people to lead lives of dignity. In contrast, even the most rousing radical critiques of liberal egalitarianism today – such as Anne Phillips’s call for ‘equality without conditions’, or Nicholas Vrousalis’s freedom-focused critique of capitalism – seem to accept the neutralist creed insofar as they eschew the perfectionist dimensions of the socialist tradition. Perhaps they are daunted by what Murdoch decried as the ‘demand for precision’ in postwar philosophy that inhibits bold approaches, compounded by an unease, perhaps with the possibility of seeming to be unrealistic or extravagant in one’s claims.

Inequality in wellbeing is the result of factors over which society can exert considerable influence

It is worth noting, however, that, for all their egalitarian shortfalls, liberal societies in this case too are not cowed by the strictures of liberal theory. Liberal philosophers’ squeamishness about making judgments about human wellbeing is in contrast with how liberal societies take a broad view of their responsibilities to their citizens, prepared to encourage some ways of life and discourage others. Public libraries, parks, galleries and museums all receive state support as a means of enabling people to engage in valuable pursuits, and these policies attract little controversy.

Human wellbeing pertains to where and how we live, whether we have autonomy and self-realisation in our work, our means of transit, the support we have for raising children, the shape of our leisure time, our physical and mental health. People can fail to flourish because they lack meaningful relationships; alienation and loneliness are rife in our times, where many lack genuine friendship and love, for all the opportunities for Facebook ‘friends’, dating apps and options to sext or hook up. Murdoch anticipated these issues back in 1958: ‘A stream of half-baked amusements hinders thought and the enjoyment of art and even of conversation.’ As we become aware of issues of depression and anxiety, and that many of us, particularly those on the autism spectrum, struggle with social connections, it seems especially urgent that we attend to inequality in wellbeing in all its dimensions. True, some of us cannot help but be sad sacks, with a tendency to cheerlessness. Nonetheless, we should be attentive to how inequality in wellbeing is the result of factors over which society can exert considerable influence.

Moreover, an ‘egalitarian flourishing’ view can tackle the problem of responsibility, not to disqualify people from amelioration of their disadvantage, but to assist the more vulnerable so that they can enjoy the flourishing that comes with contributions to society. Once we steer away from the allocation of goods and focus instead on the constituents of flourishing, recent ‘postwork’ literature should prompt us to give up productivist preoccupations and embrace a broad view of worthwhile contribution, be it that of the surgeon, the surfer or the social worker, the intellectually challenged person or the brilliant artist. Inspired by Marx’s ideals of all-round development and socialist community, a flourishing approach suggests a radical answer to a range of egalitarian issues, a robust alternative to the liberal view of political community as playing no role in people’s choices about how to live.

In sum, with his canonical treatise on justice, Rawls resuscitated political philosophy, but perhaps he did so by keeping it semiconscious. For in banning controversy about value from the domain of public debate, egalitarian political philosophy became curiously apolitical, burdened by an outlook of modest ambitions and imagination that seems ill-prepared to address the deep inequalities of capitalist societies or to motivate the activism necessary to facilitate social change. Cowed by the gains of the political Right and conservatives’ hostility to utopianism, still permeated by the legacy of scientistic philosophy, liberal egalitarianism is rather thin gruel for the aspiration to a society where people may flourish as equals. Murdoch notes her society’s ‘loss of religion as a consolation and guide’. Indeed, in the search for meaning in the largely secular societies of the West, liberal theory has left a void, leaving working people to find moral purpose in fundamentalist religion, Right-wing populism, xenophobic and authoritarian creeds. Egalitarians can and should do better.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, we have become especially aware of the essential work done in underpaid, precarious jobs, and how the most vulnerable, particularly the elderly, are inadequately cared for. Many on the Left urge that we deliver on our heightened sense of obligations to community as captured in the recent slogan (however disingenuous) that ‘we’re all in this together’. Moreover, the exceptional circumstances of the past three years have prompted valuable soul-searching about the constituents of wellbeing, how capitalist society should be reshaped so we no longer spend so many hours in cars and planes, so everyone can take walks in nature, spend more time with family, engage in acts of compassion and kindness.

We live in times in which the citizens of prosperous societies are, like never before, unequal in wealth, wellbeing and the opportunity to make meaningful contributions to their communities. Liberal egalitarianism has stepped up to shed light on these problems, but we should look again at the socialist tradition, to ‘go back and explore the other road’ as Murdoch enjoins us, to remind us of the challenging implications of the ideal of equality.