Every so often over the past decade, I’ve spent time at an ashram – a Hindu religious retreat – in the Indian city of Rishikesh on the banks of the Ganges. (For those who remember the 1960s, the ashram, called Parmarth Niketan, is about a half-mile upriver from the one where the Beatles stayed during their visits to the Maharishi.)

One of the main activities at Parmarth Niketan, unsurprisingly, is meditation. Either alone or in the company of others, I’d try to clear my mind of anything but the immediate present. I would do my best to let go of thoughts about the past and anxieties about the future. I tried to live completely in the moment and, in principle, attain perfect peace. I wasn’t very good at it.

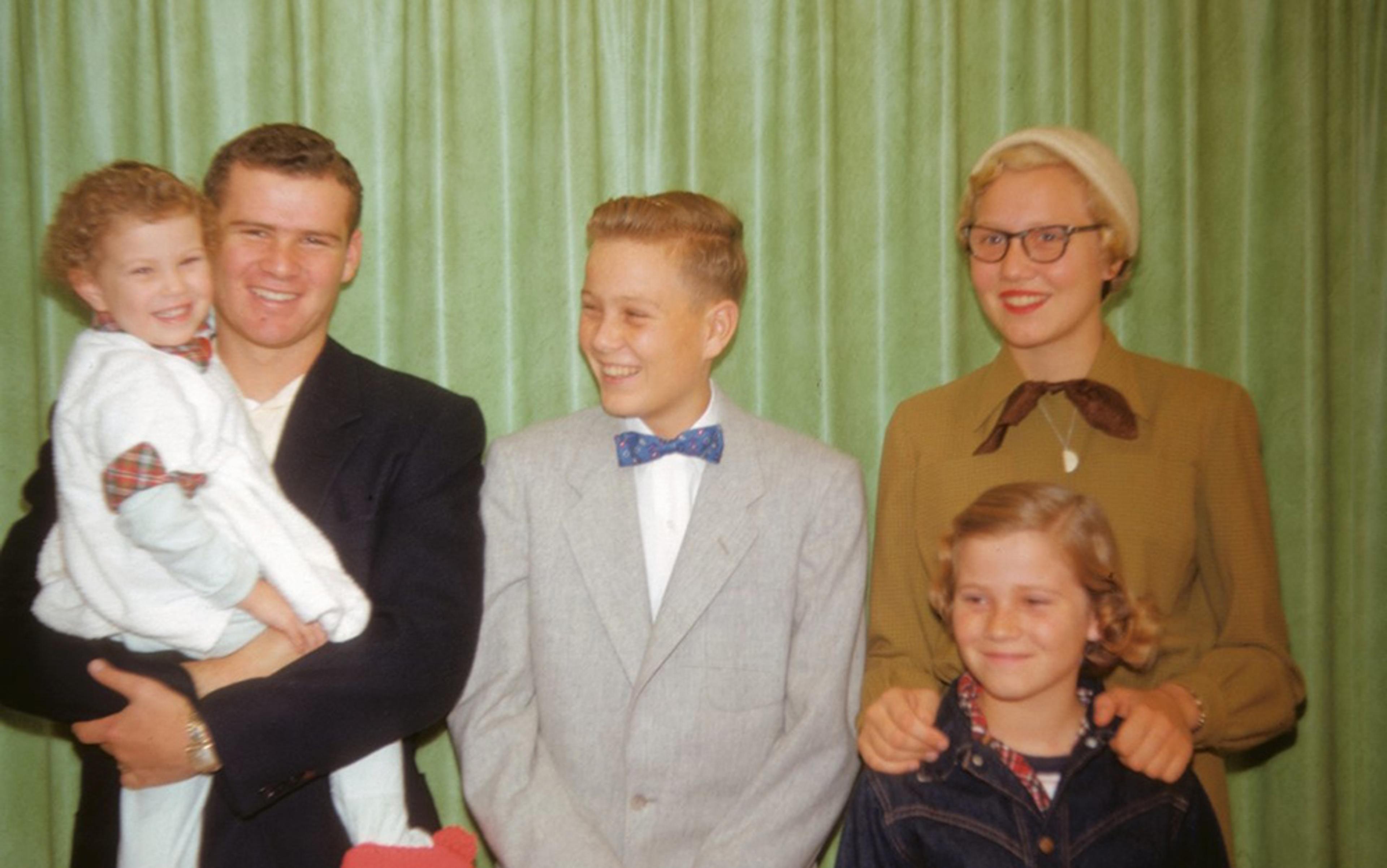

For the past few years, I’ve had a series of encounters with someone who does live almost entirely in the moment. She doesn’t do this by choice. In 2007, the herpes simplex 2 virus (HSV-2) attacked Lonni Sue Johnson’s brain. By the time it had run its course a few weeks later, Johnson, a successful commercial artist who, among other things, produced covers for The New Yorker and illustrations for dozens of other high-profile publications, had lost significant amounts of tissue in her medial temporal lobes – especially in the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure that is crucial to the formation and storage of memory.

Without an intact and functioning hippocampus, Johnson, who was in her late 50s at the time, no longer had access to most of the vast store of memories she’d accumulated over her lifetime. She didn’t remember that she had once been married. She no longer knew that her beloved father had died nearly 20 years earlier. The farm in upstate New York where she’d been living for a decade, and which she deeply loved, was completely unfamiliar. She did recognise her mother and sister, but her oldest and closest friends were now complete strangers to her.

Shockingly for a visual artist who had majored in art history, she could also no longer identify some of the best-known paintings in the world – yes to Leonardo’s Mona Lisa and Last Supper, but no to virtually anything else. Johnson was also a classical musician – a viola player – but if you played or hummed Pop Goes the Weasel or Happy Birthday or Pomp and Circumstance or Mendelssohn’s Wedding March or a Christmas carol, she couldn’t tell you what it was or the occasion where it was used. She had what neuroscientists call retrograde amnesia, the inability to recall the past.

Even worse, Johnson had so-called anterograde amnesia as well. She had mostly lost the ability to form new memories. If you met her and had a conversation – she still retained language – and then stepped out of the room for a moment, she’d have no idea when you returned that she’d ever seen you before in her life. If you stepped out a second time, the same thing would happen. It was only through constant repetition that you could get her damaged brain to store any new information – after hearing dozens and dozens of times that her father was dead, she finally got it, and it no longer came as a horrifying shock when someone mentioned his passing. Nine years later, she is still what neuroscientists call ‘densely amnesic’. If anyone can be said to live in the moment, albeit involuntarily, it’s Lonni Sue Johnson.

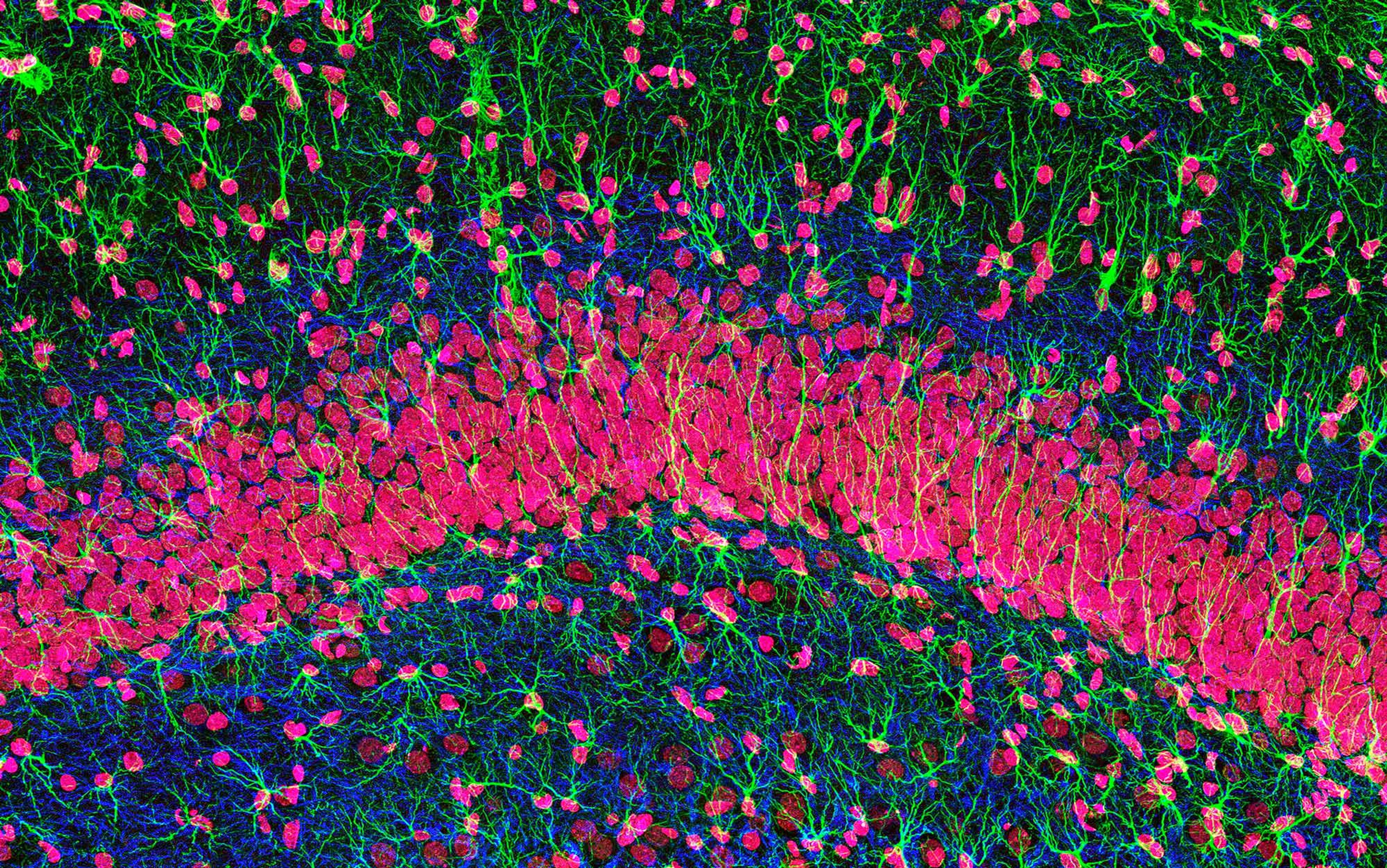

She’s not the first such person in the neuroscientific literature. That distinction belongs to Henry Molaison, better known as HM, who had his hippocampi destroyed in 1953, at the age of 27, in an experimental surgery meant to cure his severe, intractable epilepsy (‘hippocampi’ because, as with many brain structures, we have two, one in each hemisphere of the brain). At the time, nobody knew what the function of the hippocampus was. Soon after Molaison emerged from the operating room, however, it became horrifyingly clear. He recognised his parents, but no matter how many times his doctors and nurses came into the room to talk to him, he had no clue who they were. He couldn’t find his way to the bathroom, even after going several times. He had lost the ability to form new memories. That had been excised, along with his hippocampi. The surgeon, William Beecher Scoville, was appalled when he realised what he’d done.

Until he died in 2008, almost a year after Johnson was attacked by the HSV-2 virus, Molaison was likely the most studied subject in medical history. His tragedy was immeasurable, but so was his value to science. By looking at what Molaison could no longer do, and at what functions he retained, neuroscientists began to get a grasp on memory – what form it takes physically; where it’s located in the brain; and how it works. Molaison lived so much in the moment that the late Suzanne Corkin, the MIT professor of neuroscience who studied him for more than four decades, titled her book about him Permanent Present Tense (2013).

It’s impossible to overstate how important Molaison was. It was mostly from his case, for example that scientists were able to answer a question about memory that had baffled them for decades: where in the brain does memory live? The Harvard psychologist Karl Lashley tried to find out in the 1920s by training rats to learn a maze, then snipping out different parts of their brains to see how it affected their memory. It basically didn’t matter: removing brain tissue degraded the rats’ memory, but the degree of impairment had to do with how much he took out, not where he took it from. Memory, he decided, was a function of the entire brain, not a specific part.

But Molaison’s experience proved otherwise: without a hippocampus, he was profoundly impaired. Memory might be spread throughout the brain in one sense – the visual component stored in the visual cortex, the auditory in the auditory cortex, the physical and verbal and emotional components tucked away in the respective parts of the brain where those parts of the original experience were originally processed. But the hippocampus, along with the adjacent entorhinal, perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices, was clearly essential to tying them together – tagging them as related to each other, so that when you remember an experience, the sights, sounds, sensations and emotions associated with it all get reassembled into a coherent whole.

Testing by Corkin and by her mentor, the neuropsychologist Brenda Milner, of McGill University in Montreal, also showed that memory isn’t a single entity. Psychologists had suspected this was true. The British philosopher of mind, Gilbert Ryle, had pointed out that there must be a fundamental difference between ‘knowing how…’ and ‘knowing that…’ If you remember how to ride a bike, or hit a tennis ball, or anything involving what we now think of as ‘muscle memory’, it seems clearly different from the conscious calling-up of facts we normally think of as memory, if for no other reason than that you can’t describe in words how you actually do those things. You just feel it. Molaison was severely disabled with respect to the memory of facts – what neuroscientists now call memory. But he still knew how to walk and talk and mow the lawn without difficulty. He still had muscle memory, or, to use the more scientific term, procedural memory.

While he was pretty good at recalling general facts, he could remember only two autobiographical incidents from his entire life

He could also, it turned out, acquire new procedural memories, in stark contrast to his almost complete inability to form new conscious (or, more formally, declarative) memories. Milner discovered this a few years after his surgery: she asked Molaison to trace the image of a star on a piece of paper. He wasn’t allowed to look directly at the paper; instead, he could see it only in a mirror. It’s extremely awkward to do this, since your hand has to move in a direction opposite to where your eyes tell you it should go. Anyone can get better with practice, however, and that included Molaison, who tried the task several times over a period of days. He had no conscious memory the second time that he’d ever done it before, and no memory the third or the fourth time either. Nevertheless, his performance improved – a fact that took him by surprise. ‘I seem to be pretty good at this!’ he told Milner when he traced the star with relative ease after a few days of practice.

The fact that procedural memory appeared to be an entirely separate system from declarative, describable memory was one of Molaison’s great contributions to memory research. Another was that declarative memory itself appeared to come in two different flavours. We can call up general facts – the capital of North Dakota, the name of the US President who was shot in Dallas, the characters in the TV show Friends. We can also call up memories of specific incidents in our lives, such as the days our children were born, or the time we went to Paris on vacation, and what we saw there, and how excited we were to visit the Eiffel Tower. Neuroscientists call these episodic memories, because they relate to specific episodes.

While Molaison was pretty good at recalling general facts (known as semantic memories), he was almost hopeless with episodic memories. He could tell you where he’d grown up and who Babe Ruth was, and even that his parents used to take him on road trips along the Mohawk Trail, a scenic highway through the Berkshires in western Massachusetts. But he could remember only two specific, autobiographical incidents from his entire life (one was a thrilling small-plane ride, the other was the first time he’d tried smoking).

Milner, Corkin and the dozens of neuroscientists who flocked, first to Montreal and then to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to do their own tests, learned all of this and more from Molaison. It’s not an exaggeration to say that his case launched the modern study of memory, from the level of brain structures all the way down to individual cells. (Eric Kandel, the neuroscientist who showed how a neuron – a brain cell – changes physically as a memory is formed, never worked with Molaison or any other human. He did his Nobel prizewinning research on giant sea slugs. But he was inspired by the original scientific paper by Milner the neuroscientist and Scoville the surgeon that introduced Molaison’s case to the world.)

By most accounts, Molaison was generally calm and agreeable. He did whatever tasks researchers put in front of him without complaint. If you asked him what he would be doing the next day, he couldn’t be specific; among other things, his memory loss made it impossible for him to imagine the future in any concrete way. ‘Whatever is beneficial,’ he would respond.

But being stuck in a perpetual now wasn’t necessarily the reason for Molaison’s laid-back approach to life. The best evidence for this is the experience of Clive Wearing, a British musician and radio producer who developed retrograde and anterograde amnesia in 1985, in the aftermath of HSV-2 encephalitis. Unlike Molaison, he found the condition terrifying. ‘Clive showed a desperate aloneness, fear, and bewilderment,’ Oliver Sacks wrote in 2007 in The New Yorker. ‘He was acutely, continually, agonisingly conscious that something bizarre, something awful, was the matter.’ Wearing was deeply distressed by the fact that, at any given moment, he had no memory whatever of what had been going on a few minutes earlier. He was constantly certain that he had just awoken, confused, from a deep sleep; he found the inability to remember anything that had happened more than a few seconds ago utterly disorienting.

Wearing’s reaction to living in the moment was unrelenting panic; Molaison’s was to be docile and agreeable most of the time. Lonni Sue Johnson’s was and remains a sort of unrelenting joy. When you meet her, she is so happy to see you. She wants to know your name (even if you told it to her an hour ago, and yesterday, and a dozen times before that). She wants to know if you like to draw. She loves drawing, and she wants to show you what she’s working on right now. Johnson is always working on her drawings, in fact, during nearly every waking moment. She would stay up all night working on them if she had the chance, so for several years now her sister, Aline, helps her settle in for the night, talking in a gentle voice until her older sister falls asleep.

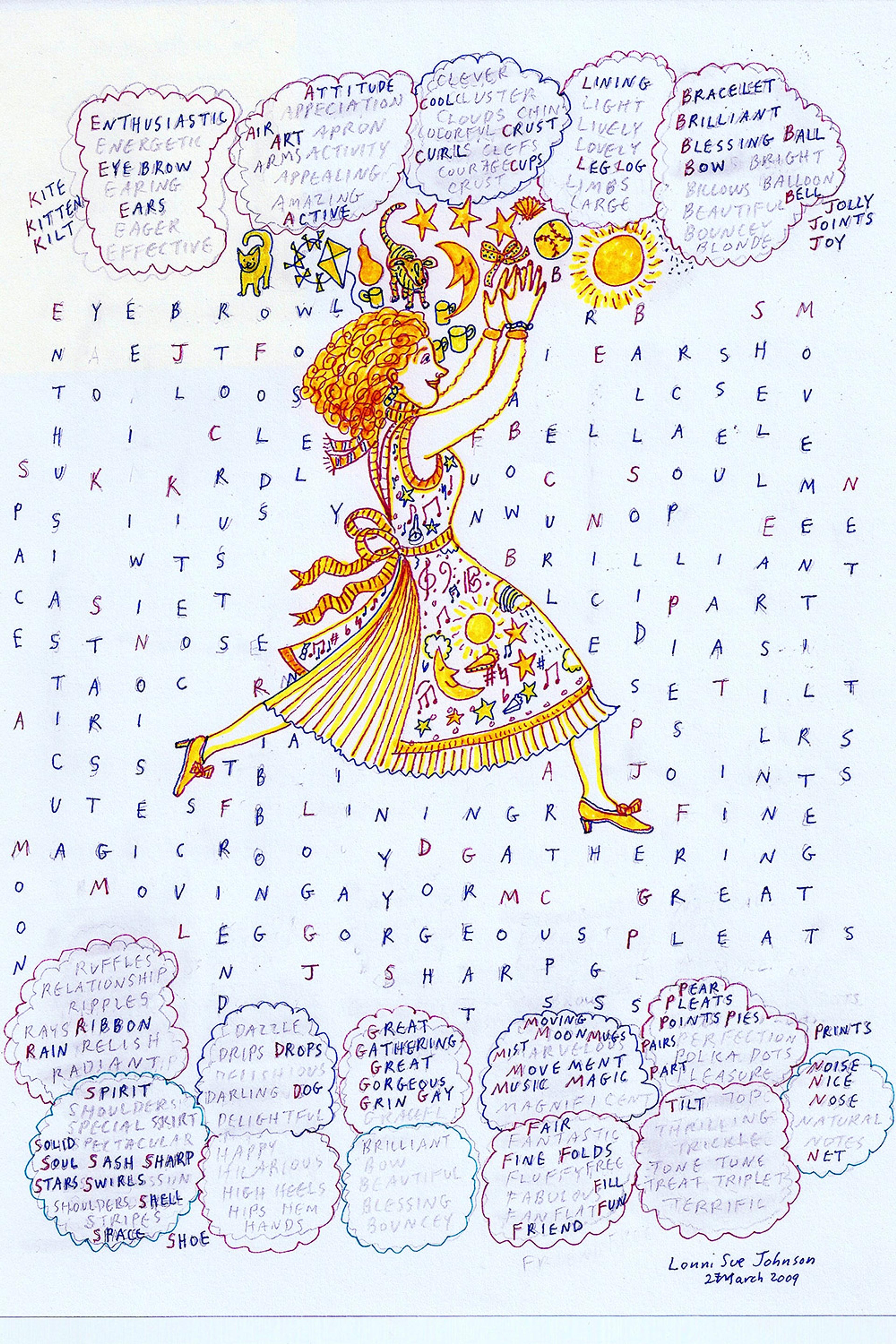

Probably the best way to describe Johnson’s temperament is ‘constantly delighted’. She’s filled with delight at her artwork, which takes the form of vividly illustrated word-search puzzles, the kind where words are hidden in a grid of letters. She’s delighted with words and letters in general: her conversation is peppered with puns (which she loved before she developed amnesia) and with verbal word-search puzzles in which she finds words hidden within words. (‘Did you know,’ she asked once, learning that a piece of music was titled Caprice, ‘that the name is made up of “cap” and “rice”?’ She was, predictably, delighted.)

Enthusiastic. Copyright 2009 by Lonni Sue Johnson. All rights reserved

Johnson is also delighted by music. She still plays the viola, she can still read music, and one of her favourite things to do is to improvise a song whose words start with the letters of the alphabet, in sequence from A to Z, and in which she makes up the melody and comes up with the words on the fly. She is impressively uninhibited: during the memorial service for her mother who died in 2015 at the age of 97, Johnson read a passage she’d written in her honour pre-amnesia; performed a short piece by Bach on her viola; sang one of her alphabet songs; and charmed the audience completely. In between, she sat next to Michael McCloskey, one of the neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where she had been studied for several years. She’s met him a couple of dozen times. She has no idea who he is.

Johnson is absurdly easy to work with, and she’s invaluable to the researchers because of her great store of knowledge and experience

Her bubbling good cheer is a gift to neuroscience: she’s almost always cooperative through the hours of testing that the Johns Hopkins group puts her through. Once she focuses on the memory task the researchers put in front of her, she’s 100 per cent there, according to Emma Gregory, who was a postdoc at Hopkins during much of the testing. ‘That’s just amazing,’ Gregory said. ‘You can get control subjects who are completely neurologically intact, and they aren’t as focused as she is.’

At Princeton University in New Jersey, where another team is studying Johnson, she goes into the claustrophobic confines of an fMRI scanner without complaint. Inside the machine, she frequently cracks up the scientists with random bits of wordplay (she cracks herself up too). The only problem is that she occasionally begins to sing and dance (as best she can) when she’s supposed to be lying still.

If Johnson is absurdly easy to work with, she’s also especially invaluable to memory research because she accumulated a much greater store of knowledge and experience than Molaison, who never went beyond high school, and whose severe epilepsy kept him from developing any special skills. His highest professional achievement was winding copper coils on an assembly line at a plant that made electric motors. Johnson, by contrast, was not only a highly successful illustrator and a talented amateur violist, but also a private pilot (she had two small planes); a small businesswoman who simultaneously managed her art business and an organic dairy on her upstate farm; and a voracious reader and writer. As a result, the neuroscientists who work with her have a vastly richer universe of scientific questions they can ask.

There’s no established protocol, however, for probing an amnesia victim on the sorts of knowledge Johnson gathered in her lifetime. The neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins started at the most basic level they could think of – the ‘Who painted this?’ test, which she pretty much failed. Her semantic memory about art and artists, her primary area of expertise, was significantly impaired. Remarkably, though, when the scientists included some of her own artworks in the testing, she correctly flagged every one as hers. Even more surprising, when the researchers added drawings done in a style somewhat similar to Johnson’s, she picked them out as artworks she might have produced. To do so, she had to be drawing on some sort of memory. It clearly wasn’t episodic memory, since artworks aren’t events – but it’s unclear that it qualifies as semantic memory either, since it addresses an ineffable quality, not a set of facts. ‘I don’t think we know how to characterise that sort of memory,’ Barbara Landau, one of the Johns Hopkins scientists, told me in an interview.

Then the scientists went on to test Johnson’s knowledge of how you create a piece of art. Within a year of developing amnesia, Johnson had taken up drawing again. It’s not surprising that she was able to do so: you’d assume that the physical act of making art was lodged in procedural memory. As Molaison showed, this is left relatively undamaged when you lose your hippocampus. What was surprising – astonishing, really – was that she could answer explicit questions about how one would go about making a watercolour or a pen-and-ink drawing. She could explain how you create the illusion of depth. She knew what sorts of brushes you use for an oil painting versus an acrylic. She could talk about the principles of design. To this day, none of the scientists can explain how her damaged brain can access this information.

The surprises continued when the scientists switched from art to music. She failed tune-recognition tests that a third-grader would have passed. But then the Hopkins team had her bring out her viola and practise a music-learning test they’d created especially for her (unlikely as it sounds, they had managed to find a Hopkins undergrad who was majoring in neuroscience and was also an accomplished viola player). In a series of practice sessions, Johnson would play through the very difficult tune; then the scientists would take away the sheet music and put it back again. She had no idea she’d seen it before – this was the piece titled ‘Caprice’ – and she made the same, delighted comment that the word was made of ‘cap’ and ‘rice’ every time. Like Molaison tracing a star, she got better with practice. Learning to play a difficult new piece of music, however is a far more cognitively difficult task: it involves not just motor skills, but also a conscious monitoring of pitch, tone and tempo, with constant adjustments to all three in order to make the music sound as good as possible.

Finally, the group tested Johnson on her knowledge of aviation – the parts of an airplane, how you compensate for different sorts of wind conditions, the rules and regulations a pilot has to know and more. (They didn’t take her up in a plane to take the controls herself, which would have been insanely risky – but they’re still considering putting her in a flight simulator). Again, she defied the conventional neuroscientific wisdom. Without a hippocampus, which in principle should have cut her off from a lot of explicit, factual information she used have, Johnson could still talk knowledgeably about flying. ‘She doesn’t know everything,’ Gregory told me. ‘But she knows a lot.’

Johnson illustrates something memory researchers were already starting to realise before she came along: the divisions of memory suggested by Molaison’s case – declarative memory for lived events, stored in the hippocampus, on the one hand; and procedural memory for physical skills, not in the hippocampus, on the other – were far too simple.

Take the bit of knowledge ‘Paris is the capital of France’, which comes from semantic memory – you almost certainly don’t remember having learned it. But there must be a time when you did learn this fact for the first time. In the day or week afterward, it would have been an episodic memory. Five years later, you might no longer remember the episode; just the fact. Or, in one of the examples a neuroscientist gave me, imagine that you remember that you went to the high-school prom. Molaison could pull up such facts, but they were considered semantic, lacking in any specific detail. What would qualify such a memory as episodic, though? Would remembering who you went with be enough? Would you also have to remember whom you talked to? What you talked about? And what they served for dinner? It turns out that there’s no easy way to draw a line between these two types of memory, even though one is more severely impaired than the other when the hippocampus is damaged.

Researchers have also come to understand that we have some kinds of memory that don’t fall into any of these categories. The scientists at Princeton have tested Johnson on something called ‘statistical learning’ – a process by which we unconsciously pick up on and absorb information about the world without ever noticing that we’re doing so. When you drive a new route in your car, for example, you have to pay close attention to what the map (or the written directions or the GPS) are telling you. If you drive the same route over and over, you brain relies instead on patterns – when you see the Starbucks on a corner with a bank opposite, you know you’ll be turning right at the next traffic light. You never consciously memorised this; you just recognise it. Until Johnson came along, it wasn’t clear whether the hippocampus was involved in this sort of learning or not. It turns out that it is: she can’t do statistical learning.

But she can do adaptive learning – the process by which we learn which sights, sounds and objects in our environment need our attention and which don’t (we learn, again unconsciously, that a car passing in the other direction as we drive down a highway barely registers; a car that suddenly veers toward us sounds major alarm bells). The role of the hippocampus has been unclear here as well. The conventional wisdom said it was probably necessary. The tests on Johnson say not necessarily.

In three or four years of testing, neuroscientists have barely scratched the surface of what they expect they can learn about memory from Johnson. The good news is that she’s only 66, and in excellent health. There’s no way she’ll equal Molaison’s record of more than a half-century of service to the science of memory. But given what researchers have learned about her so far, she could easily contribute every bit as much. And all indications are that she’ll continue to do so with enthusiasm and joy – without much thought about the past or the future.