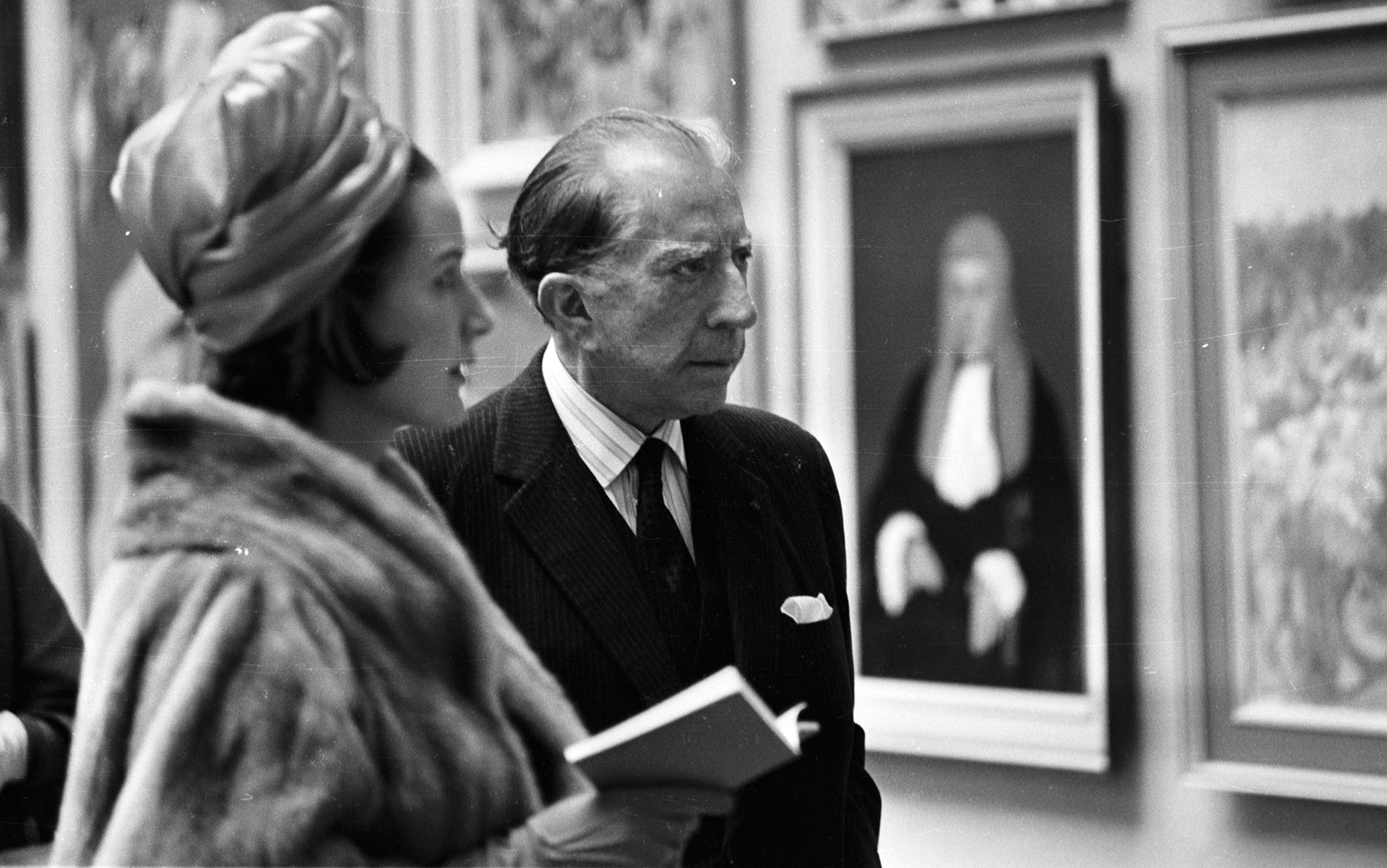

The oil billionaire J Paul Getty was famously miserly. He installed a payphone in his mansion in Surrey, England, to stop visitors from making long-distance calls. He refused to pay ransom for a kidnapped grandson for so long that the frustrated kidnappers sent Getty his grandson’s ear in the mail. Yet he spent millions of dollars on art, and millions more to build the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. He called himself ‘an apparently incurable art-collecting addict’, and noted that he had vowed to stop collecting several times, only to suffer ‘massive relapses’. Fearful of airplanes and too busy to take the time to sail to California from his adopted hometown of London, he never even visited the museum his money had filled.

Getty is only one of the many people through history who have gone to great lengths to collect art – searching, spending, and even stealing to satisfy their cravings. But what motivates these collectors?

Debates about why people collect art date back at least to the first century CE. The Roman rhetorician Quintilian claimed that those who professed to admire what he considered to be the primitive works of the painter Polygnotus were motivated by ‘an ostentatious desire to seem persons of superior taste’. Quintilian’s view still finds many supporters.

Another popular explanation for collecting – financial gain – cannot explain why collectors go to such lengths. Of course, many people buy art for financial reasons. You can resell works, sometimes reaping enormous profit. You can get large tax deductions for donating art to museums – so large that the federal government has seized thousands of looted antiquities that were smuggled into the United States just so that they could be donated with inflated valuations to knock money off the donors’ tax bills. Meanwhile, some collectors have figured out how to keep their artworks close at hand while still getting a tax deduction by donating them to private museums that they’ve set up on their own properties. More nefariously, some ‘collectors’ buy art as a form of money laundering, since it is far easier to move art than cash between countries without scrutiny.

But most collectors have little regard for profit. For them, art is important for other reasons. The best way to understand the underlying drive of art collecting is as a means to create and strengthen social bonds, and as a way for collectors to communicate information about themselves and the world within these new networks. Think about when you were a child, making friends with the new kid on the block by showing off your shoebox full of bird feathers or baseball cards. You were forming a new link in your social network and communicating some key pieces of information about yourself (I’m a fan of orioles/the Orioles). The art collector conducting dinner party guests through her private art gallery has the same goals – telling new friends about herself.

People tend to imagine collectors as highly competitive, but that can prove wrong too. Serious art collectors often talk about the importance not of competition but of the social networks and bonds with family, friends, scholars, visitors and fellow collectors created and strengthened by their collecting. The way in which collectors describe their first purchases often reveals the central role of the social element. Only very rarely do collectors attribute their collecting to a solo encounter with an artwork, or curiosity about the past, or the reading of a textual source. Instead, they almost uniformly give credit to a friend or family member for sparking their interest, usually through encountering and discussing a specific artwork together. A collector showing off her latest finds to her children is doing the same thing as a sports fan gathering the kids to watch the game: reinforcing family bonds through a shared interest.

Even the seeming exceptions prove the rule. Another wealthy oilman, Calouste Gulbenkian, accumulated a fabulous art collection and called the works ‘my children’. Mostly ignoring his flesh-and-blood son and daughter, he lived to serve his art. Claiming that ‘my children must have privacy’ and ‘a home fit for Gulbenkians to live in’, he built a mansion in Paris with barricades, watchdogs and a private secret service. He routinely refused requests to loan his art to museums, and did not allow visitors, since ‘my children mustn’t be disturbed’. But even this extreme of a collector who prefers art to people shows the importance of the social role of collecting, since Gulbenkian simply treated artworks as if they were people. And, when Gulbenkian left his collection to found an eponymous museum in Lisbon upon his death in 1955, he showed that he cared about people after all – just not the ones he happened to know.

Collectors are not only interested in creating social links; they are also motivated by the messages they can send once these social networks are created. We all know that art is a powerful way for the artist to express thoughts and feelings – but collectors know that art can serve as an expressive vehicle for collectors too. Many thus carefully curate their collections, purchasing only artworks whose display backs up a claim that the collector wishes to make.

Almost always, this claim is about the identity of the collector. Like sporting a nose ring or carrying a public radio totebag, displaying art can send a message about who the collector really is – at least who she sees herself as. From the beginning of art-making, we have believed that artworks capture and preserve the essence of their makers and even their owners. As identity can derive from lineage, owning artworks is therefore also a way for an owner to communicate with the past. In art collecting, the past is usually about the collector’s perceived affiliations with notable people.

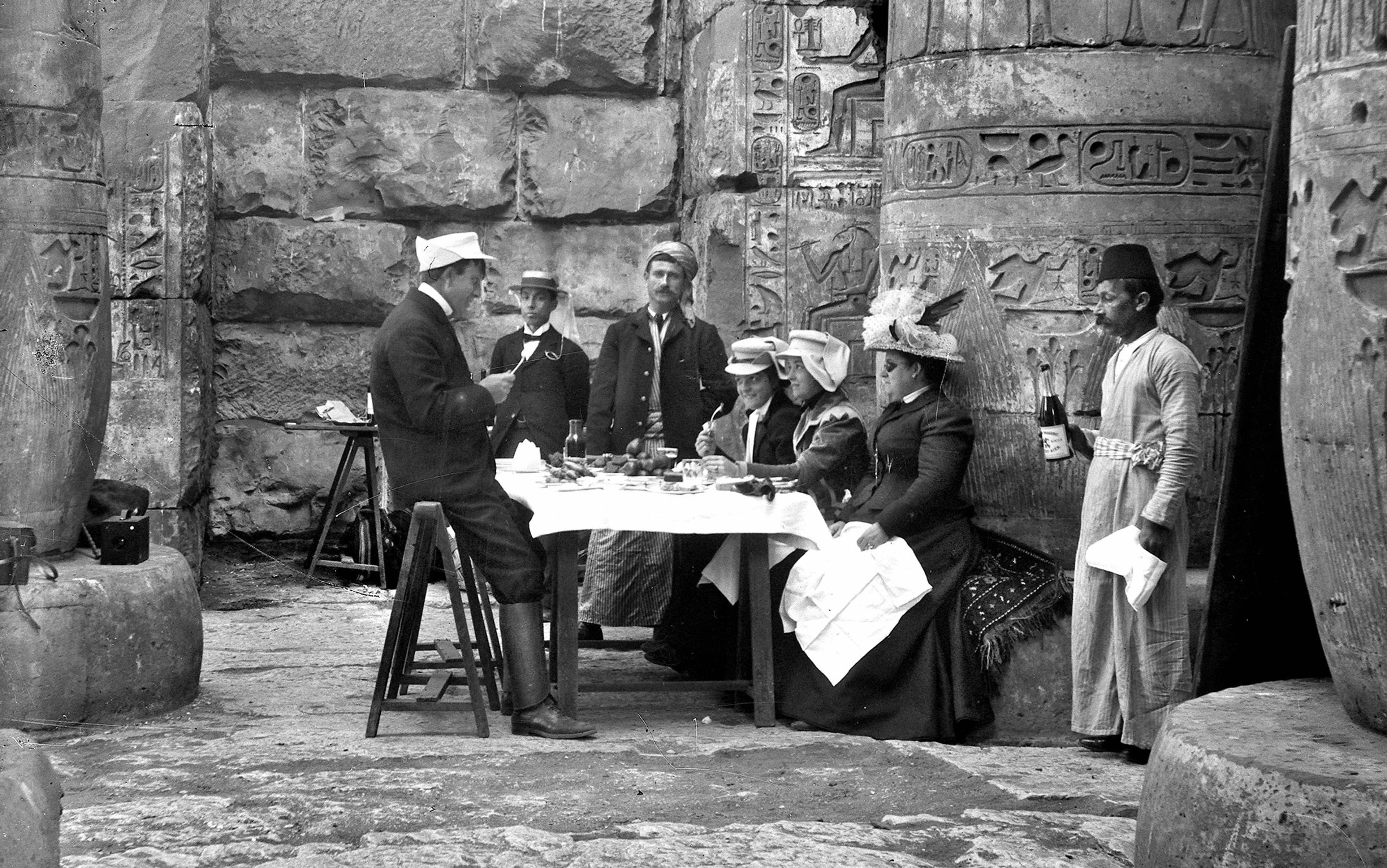

The Attalids were probably the first art collectors to lay claim to an august lineage. After the death of Alexander the Great, one of his generals left a treasure of 9,000 talents in the care of his treasurer Philetaerus in the small but strongly defended hilltop town of Bergama, on the western coast of modern-day Turkey. Philetaerus promptly betrayed his master by locking the town’s gates and using the treasure to establish his own kingdom. The new dynasty, known as the Attalids, went to great lengths to acquire as many artworks as possible from a high period of Greek art. King Attalus I even purchased an entire island, the art-rich Aegina, just off the Greek mainland, and then denuded its towns and sanctuaries of artistic masterpieces to decorate Pergamum.

The Attalids surrounded themselves with Greek art because they needed to appear to be Greek, and thus the legitimate successors to Alexander the Great – despite their betrayal of his general. The other dynasties that ruled the area around the Mediterranean during this period – the Seleucids, Antigonids, and Ptolemies – were actually descended from Alexander’s generals. They could thus justify their continued rule over the native populations by their connection to Alexander the Great, whose fame and authority shone for centuries. Indeed, maintaining proper bloodlines was so important to the Ptolemies, who ruled Egypt, that their kings routinely married their sisters, so as to not introduce foreign ancestry. Cleopatra, the last of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt before their full conquest by the Romans, was married to not just one but two of her brothers, in succession. She had time for affairs with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony as well, perhaps because, unlike the Attalids, she did not need to amass an art collection to prove her political authority.

Vast numbers of dynasties and politicians, from Charlemagne to Saddam Hussein, have followed the Attalids’ example, collecting art to communicate messages about themselves in order to justify their rule. On a smaller scale, individual collectors have acted out of the same motive. For example, Getty pouring millions of dollars into art makes much more sense when we think about how his purchases gave him an alternative identity: as a sophisticated European rather than an uncultured American.

Getty was not even from New York or Boston. He grew up in the scraped-together oil-boom towns of the Great Plains and the brand-new expanses of Los Angeles. But he made his first million by the time he was 24, prospecting for oil in Oklahoma in 1916. He promptly retired, declaring that he would henceforth live a life of enjoyment of beaches and fast cars. But Getty’s California idyll proved to bore him, and he began to work again after little more than a year. He did so for the rest of his long life, travelling constantly, sleeping little, trusting few, and accumulating a vast fortune – at $2 billion by the time of his death, thanks to Getty Oil’s worldwide network of oil production and distribution.

When Getty started to collect art, his focus on buying Greek and Roman antiquities went against the American zeitgeist. The 19th-century traveller Ralph Izzard Middleton of South Carolina expressed a characteristic American perspective on ancient art. After seeing the Belvedere Torso in the Vatican Museum, he wrote in a letter to his family that artists should go to look at it, but for people ‘who could not model a dog out of a piece of wax (among which I enroll myself) to go and spend hours together in the middle of winter in the Vatican constantly exclaiming how beautiful, how beautiful, when they are all the while thinking how cold, how cold, this I think utterly absurd’. In the same letter, he huffs that ‘triumphal arches and old tottering columns, the dilapidated statues and smoked frescoes, all these are fudge’.

Getty’s most important investment was in the identity-granting power of art

Middleton’s attitude (seemingly shared by many of the drooping tourist groups marching through Rome today) was characteristic of 18th- and 19th-century Americans. Classicism was simply never popular on a wide scale in the US. Perhaps because Americans formed a nation on the claim that their country broke decisively with the Old World, large-scale collections of antiquities seemed incongruous. Classical art collections, after all, were associated with European aristocracy, especially the same 18th-century English elite against whom Americans had rebelled.

Getty was different. He was obsessed with showing kinship with these very aristocrats. He consumed himself with his self-imposed goal of fluency in European cultures. He could have easily afforded the best translators, but he learned languages from records, practising alone late at night in his hotel rooms. Languages were not the only way he sought to blend in to the different cultures through which he travelled. He ‘did not mimic manners and mannerisms. He assumed them,’ as one of his wives describes, calling the result his ‘perfect coloration’.

But his most important investment was in the identity-granting power of art. Getty above all preferred to acquire antiquities previously owned by the emperor Hadrian or by 18th-century English aristocrats – or, ideally, by both, as he believed was the case for the Lansdowne Hercules. He purchased this sculpture from the noble English Lansdowne family, who had possessed it since its purchase in 1792 by the first Marquess of Lansdowne, after it was reportedly excavated at the site of Hadrian’s Villa in 1790.

Getty elevated this claim, which might have been merely part of the sales pitch offered by the 18th-century dealer, into a direct connection with Hadrian. He boasted that ‘there is evidence to suggest that this… statue was a great favourite of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, who was the most sophisticated of all ancient Roman emperors’. He was thrilled that his purchase of it meant that ‘this magnificent marble sculpture, which once delighted the Emperor Hadrian and for a century and a half was a pride of Britain, is now completely “Americanised” – on view for all to see at the Getty Museum’. There, all those whom Getty had left behind could see the proof that he was just as elevated as the former owners of his art.

Other art collectors see their collections as having a broader power – to convey messages not just about themselves, but about the world as a whole. For example, the kid with the shoebox of bird feathers might show others her collection not just to make friends, but also to convince them about the importance of protecting endangered species. One such collector was Elie Borowski, who thought his collection of antiquities could prevent another Holocaust.

Born in Poland, Borowski spent most of the Second World War interned in Switzerland, where he was allowed to work part-time at a museum in Geneva. There, in 1943, he saw an ancient Near Eastern cylinder seal that sparked his interest in collecting antiquities. He wrote about this moment that the seal’s inscription, ‘le-Shallum’, ‘had a strange fascination for me, even though I suspected that my interpretation that it referred to Shallum ben Yavesh, king of Israel in 741 BCE, was doubtful. I was… working in the museum in a state of emotional isolation and deep depression, for I had already known for a year of the fate of my family in Warsaw.’

Borowski’s family – he was the sixth of seven children – had been killed by the Nazis. For him, as a collector, it makes absolute sense that seeing an artwork would bring up thoughts about his family, even if separated by thousands of miles and thousands of years.

Isolated and depressed, Borowski seized upon an antiquity that inspired in him notions of a very different state of affairs, a time when the Jews possessed a powerful and feared state. Even though he knew that the seal he held, and ultimately purchased, probably did not actually refer to a king of Israel, it caused him to plan a collection:

I visualised, perhaps dreaming, that the acquisition of this [seal] might form the beginning of a spiritual apothecary, filled with healing, cultural medicines which would prove to be efficacious against the horrors of those times [that is, the Second World War]. How wonderful it would be if I succeeded in forming a collection of works of art, the aim of which would be to strengthen the historical truths of the Bible, and thereby challenge individuals to rise above their ephemeral materialism in order to return to the eternal, spiritual values and beauty of the Bible and humanism. Thus began my collection of the art of the ancient world and the Bible.

Only a true collector would think that art’s power to tie people together could give a helping hand to the Bible.

Borowski was one of the many people who, after the horrors of Nazism, thought that society needed to be reconstituted on a new foundation to ensure that similar regimes could never again arise. He thought that Biblical morality and Greek humanitarianism, revived, would protect us. Accordingly, Borowski ‘solemnly pledged’ that he would ‘dedicate my life to creating a world centre for education about biblical cultures and art history’. He founded first the Lands of the Bible Archeology Foundation in Toronto in 1976 and then the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem in 1992, to which he donated more than 1,700 objects from his collection, along with nearly all the $12 million construction cost, having made his fortune as an art dealer. Just like Getty, Borowski invested heavily in communicating his message to the world.

But there is a downside to such a vision. Borowski’s feelings about the purpose of his collection were so strong that it overcame any scruples he might have had about antiquities laws. He bought directly from notorious smugglers, becoming one of the most important participants of the illicit trade in looted antiquities. Nor did he deny it. Batya, Borowski’s wife and partner in his museum-founding vision, responded to questions about the questionable origin of many of their collected antiquities by saying: ‘You’re right. It’s stolen. But we didn’t steal it. We didn’t encourage it to be stolen. On the contrary, we have collected it from all over the world and brought it back to Jerusalem. Elie’s not a stealer of artifacts. He has saved and preserved so much of our history and heritage by collecting these artifacts.’

Today, looters are attacking archeological sites from all periods and cultures of the past – from ancient Greek and Roman to Native American sites in the US. The problem of looting shows no signs of abating. Indeed, the reverse is true, with recent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, Syria and Yemen creating new opportunities for theft.

Understanding that art collecting is primarily a social activity is essential to addressing the problem of looting, and cultural theft. First, art moves through social networks. There are only so many possible buyers or destinations for valuable antiquities. Second, these social networks of art are so strong, and so important to collectors’ identities, that persuading collectors that what they are doing is harmful is extraordinarily difficult. It involves effectively convincing collectors that their past conduct, something they have almost certainly understood as an expression of their best possible self, their highest aspirations, has actually been harmful. It means, in effect, repudiating the bonds they have formed with other collectors. And, as Getty was hardly the first or the last to discover, that is a hard addiction indeed to overcome.