The world’s most famous palaeontologist doesn’t understand why anyone wants to collect dinosaurs. Mark Norell sits across from me in his expansive corner office at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and launches right in: ‘People are weird. I think: “Who is buying this shit?” No accounting for people’s taste. I have a passion for dinosaurs, but certainly not what I would call “dinosaur insanity”. Dinosaurs are just a medium for me to do science. But if I were doing the same thing on some other organism – you wouldn’t be here.’

I first heard about private dinosaur-collecting in 2007, when the actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Nicolas Cage engaged in a bidding war over a 32-inch Tyrannosaurus bataar skull at an auction in Beverly Hills. In the end, Cage outbid his rival via a $276,000 offer. (Just before Christmas 2015, Cage returned it on order of the department of Homeland Security; unbeknown to him, he had bought a dinosaur part smuggled out of Mongolia.)

Since that auction, I perk up whenever I see news about any other big-name dinosaur collectors: the film directors James Cameron and Ron Howard, actor Brad Pitt, and Nathan Myhrvold, Microsoft’s former Chief Technology Officer who, according to Men’s Journal, has a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton in a glass solarium in his large home in Bellevue, Washington. Various high-flying sheikhs are in on the pastime, too. And regardless of what his Republican colleagues think about evolution, the former US House Speaker Newt Gingrich kept a T rex skull cast in his office.

As I read more about this current crop of rich male (always male, it seems) collectors, I gave them their own species name: Abundus egocentrus. I tried to understand their motivation. Was having a big vicious dinosaur on display akin to owning a huge scary dog like a Rottweiler? Were they saying to the world: ‘Look what I can tame! Look what I’m not scared of! I’m ruthless, too!’ Or maybe there were deeper psychological implications. Did collecting dinosaur fossils tap into childhood issues, delivering a soothing narrative about where we came from? Whatever the answer, there was something about this topic that was infectious and persistent enough to merit an investigation.

My first step for getting answers was to talk to the person that Time magazine nicknamed ‘Dino Man’. Norell was the cover boy for their Time for Kids issue of November 2015, distributed in thousands of elementary schools in the United States. Who better to explain the mindset of those amassing dinosaur bones than the man who oversees the dinosaurs that attract 5 million visitors a year?

Norell, surprisingly chatty and undeniably hip, is the 58-year-old Chairman of Palaeontology at the American Museum of Natural History. He’s best known for excavating dinosaurs sitting on nests, baby dino embryos fossilised beneath their haunches, not to mention his storied work on feathered theropods. Just back from a fossil tour of China, Norell was ready to go out in the field again, somewhere in the Gobi Desert. By good luck, I reached him during a brief moment of immobility.

When I unexpectedly scored my interview, I swiftly transformed myself into a walking version of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Dinosaurs. By the time I arrived at the museum’s grand Central Park West entrance, I was ready to chat fluently about the English naturalist Mary Anning who, in 1811, found a uniquely complete skeleton of an ichthyosaur – an ancient reptilian version of a dolphin – along the coast in Lyme Regis, Dorset. She was all of 12 at the time. When her brother Joseph decided to concentrate on upholstery, Mary became the main collector in the now fatherless family. The tongue-twister ‘She sells seashells by the sea shore’ was inspired by her local fame and collecting passion.

After learning of Anning’s spectacular discoveries, a fellow Brit, Gideon Mantell, caught the fossil bug. He did very well at the task, aided by his wife (also a Mary), who in 1822 found a large fossilised tooth while poking around on the side of the road during a casual stroll in Cuckfield, West Sussex. The discovery inspired her husband to search a local sandstone quarry called Whiteman’s Green for more fossils to match it. He concluded that the remains had come from a beastly creature that Mantell christened ‘iguanodon’ because its teeth resembled those of the modern iguana, though 20 times longer.

I had also channelled the passions of William Buckland, the progressive British priest who was also a prodigious fossil-hunter. At the Geological Society of London in 1824, his paper ‘Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield’ caused quite the fuss. Through fragmentary finds, Buckland named and defined the first dinosaur, though without actually using that word. We owe the name Dinosauria, or ‘terrible reptile’, to Sir Richard Owen who in 1841 concluded that the already discovered iguanodon, megalosaurus and another fossil creature named hylaeosaurus were all species of a new prehistoric reptile order.

In the 1870s, the fossil-collecting frenzy spread across the pond and found its way westward into northern Wyoming. There, an extreme rivalry brewed between two titans of early US paleontology: Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh. Historians refer to their long ugly feud, which saw them jostling for scientific supremacy and using underhand methods to discredit each other, as the Bone Wars. Yet, despite the enmity, together they named 136 dinosaur species by 1892.

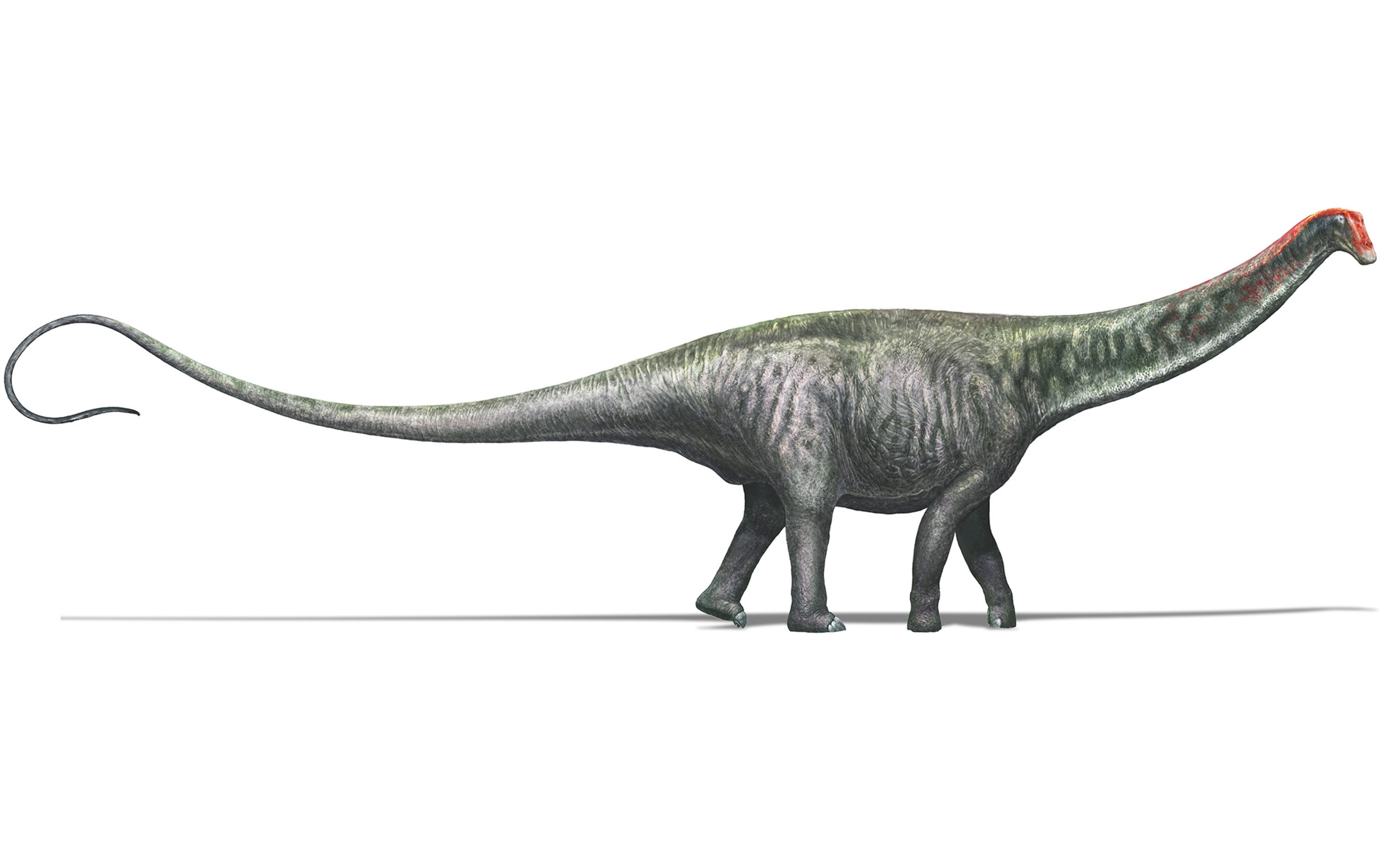

Collecting mania in the US intensified again at the tailend of the 19th century. On 11 December 1898, The New York Journal and Advertiser ran a headline that caught the fancy of many, including the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie: ‘Most Colossal Animal Ever on Earth Just Found Out West’. The titillating copy featured a Brontosaurus giganteus peering into the New York Life building to illustrate the size of the find. It was not a factual story – only a single leg bone was found in Laramie – but the filthy-rich Carnegie was now longing for a dinosaur of his own. He financed great discoveries including ‘Dippy’ (Diplodocus carnegii), comprised of fossils unearthed along Sheep Creek in Wyoming, and a startlingly large dinosaur named after his wife (Apatosaurus louisae) pieced together from finds in his private quarry in Vernal, Utah.

Norell, a dinosaur historian as well as a curator and scientist, adores stories of his predecessors, and has co-authored a book about one of the most famous dinosaur fossil-hunters before him, Barnum Brown, the colourful man who, back in 1902, discovered the iconic T rex. ‘Dinosaur devotees know Brown as “Mr Bones”,’ Norell says, and gestures to the antique long wooden desk where he works. ‘That’s his.’

Flicking back a strand of shoulder-length hair, Norell adds that the old collectors make for great stories but today there is a professional goal to leave sites uncontaminated. ‘I’ve learned to never let dinosaur excitement get in the way of science,’ he says. ‘When you locate a fossil, you never really know how good it is until you get it back to the lab and technicians have worked it all out. That’s when I get the rush: in the science of the thing, not in the collecting.’

In Norell’s view, dinosaur collectors are not merely harmless science wannabes. They cause serious saurus tsuris for those in the museum world. ‘Prices have ballooned for the unanticipated finds on private land. Museums don’t have the funds to compete with the actors and hedge-fund guys. If there is a great amateur discovery, don’t you think it should advance science?’ He also pooh-poohs reports that you can make a fortune in dinosaurs because, as he puts it, you can always get more for a Seurat than a stegosaurus. ‘And keep in mind they are incredibly not liquid. You can’t say: “Oh I need some money, I’m going to sell my Bambiraptor.”’

The highest-priced dinosaur ever offered by a private seller was Sue, the largest T rex specimen ever found, which back in 1997 reportedly even attracted a bid from Michael Jackson. After the pandemonium died down, the Field Museum of Chicago was the victor. ‘What’s $8 million and change to someone who invests in art? And that sale was a one-off, it really didn’t happen again,’ Norell sniffs. More recently, Bonhams in New York touted the auction of a theropod and a large horned ceratopsian locked in mortal combat. ‘Well, let me tell you what the auction houses won’t tell you,’ he continues. ‘For all that publicity, it was a no-go. The guys who excavated thought they’d go to the Bahamas forever. Instead, they didn’t make reserve.’

‘I have been in people’s houses where every possible inch is covered in fossils; even the dishwasher has trilobites in it’

Norell doesn’t own any dinosaurs. As part of any major museum contract, no curator can collect in the area where he studies, nor is he allowed to authenticate or appraise fossils for private sale. As for the ones that surround Norell now at his famed museum, he says: ‘I guess there are a few around here that are cool, but I sure as hell wouldn’t want them in my house.’ What you will find is an extensive collection of Himalayan art, to which Norell has devoted an ‘embarrassingly good deal’ of his free time. ‘But I’m sort of now moving more to 19th-century Scandinavian painters. I just caught that fever.’

I press him: what motivates the collectors? ‘Honestly? Some people are rabid collectors and some people aren’t. I like the research aspect of collecting art, developing cultivated rarified tastes, and my satisfaction when I know something is good.’ He raises a finger. ‘But there’s another segment I’ve come across, especially in the fossil world, which is kind of like hoarders. All they want is more stuff. I have been in people’s houses where every possible inch of their home is covered in fossils; even the dishwasher has trilobites in it. I’ve met a lot of collectors who have OCD or are compulsive gamblers. There are very few specialist dinosaur collectors who collect only dinosaurs. Usually the people who collect dinosaurs collect all kinds of fossils. They’ll have ammonites, and sea creatures, mammals and then a few dinosaurs.’

If you want to really get into the head of the collectors, Norell advises, meet with some private dealers to get their perspective. ‘I’ll forewarn you, though, some are shadier than others, and there is a hidden world of secretive dealers, average Joes without a store who trade at fossil shows, almost a Silk Road of dinosaur-dealing.’

A lot of the visible trading happens in Tucson, Arizona, at an annual mineral and fossil show held at the beginning of February. ‘People come from all over the world. They always have someone there from Homeland Security, and ICE (the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement),’ Norell says. ‘You’d be surprised how stupid some people are. Last year, a few people were arrested for trafficking dinosaurs from countries that forbid sales outside of their country. If I see something especially egregious, I’ll call Homeland Security myself.’

As Nicolas Cage found out, even big-time buyers can fall foul of anti-smuggling laws. Some of the sellers can knowingly skirt the law. ‘Crazy stuff goes to Dubai, to Qatar, and pretty regularly to Singapore. And there are all sorts of big odd collections in Germany. Mandatory retirement while they’re in good health – all those German guys pick weird hobbies to pass their twilight years,’ Norell tells me. Despite his gripes, he says he genuinely likes some of the private fossil dealers. Among his favourites, he names Peter Larson, the man behind the sale of Sue the T rex. ‘Pete excavates world-class specimens and tries to do the right thing; at least 80 per cent of the high-end dealers do their best to place the important specimens in the hands of museums.’

Larson’s base is in the Black Hills of South Dakota, but plenty of dino-dealing takes place right near my Manhattan home. A year prior to my conversation with Norell, I’d seen a velociraptor claw for sale in a fine-gems store on Fifth Avenue, across the street from Lord & Taylor. I head across Central Park to follow my hunch that I’d find more dinosaur parts there if I spoke politely to the management.

‘You have to find someone with a big house with a big budget who wants to live with a T rex’

Astro Gallery of Gems is the largest gem and mineral store in the world, whose devoted clients have included Salvador Dalí and John Lennon. As I suspected, it is also a dinosaur dealership on the side. ‘Dinosaurs are not as easy sales as you think,’ Dennis Tanjeloff, the 48-year-old President and CEO of the 55-year-old multigenerational establishment, confides to me. His subterranean office is heavily guarded with expensive digital security; this netherworld below their upstairs public gallery is filled with glinting gemstones and a strange assortment of ancient bones.

Tanjeloff offers me a Coke from the little refrigerator near his desk and notices me eying a pterodactyl-like skeleton a few feet away. ‘You like my little guy? He’s an Odontopteryx toliapica, a prehistoric waterfowl. $125,000. Expensive stock, right? So if you are me, number one, you have to find buyers. Number two, the size of these things! You need room to display them. These are not for New York City apartments. Then you have another problem: you have to have a small group of people that actually appreciate them, and just because someone’s an appreciator doesn’t mean he wants to be an owner. You have to find those three elements together. You have to find someone with a big house with a big budget who wants to live with a T rex.’

Tanjeloff describes his ideal dinosaur customer as a grown-up boy who never got over the revelation that prehistoric creatures were real, or that they were on this planet so many million years ago. I agree that we all know that kid who picks his favourite dinosaurs, learns their names and families. ‘Yes, that’s the one. As he got slightly older, he began to process what 200 million years means, and was still enraptured by the thought of a creature that ate three tons of vegetation a day and needed 3,000 teeth to chew dinner.’

Like Norell, Tanjeloff does not keep fossils for himself, but has a lot of appreciation for the impulse to collect. He talks about the long history collecting minerals and fossils. ‘It all goes back 4,000 years, to kings and queens, crown jewels. The Egyptians were collecting gems and trading gems and showing wealth and power, there has always been ivory.’ Back in 1908, he adds, the American Museum of Natural History shipped giant T rexes in from the Badlands of Montana. ‘You ever heard of Barnum Brown?’

‘I just saw his desk!’

‘Well, that guy brought the museum publicity up the wazoo. I think they based Indiana Jones on him. And every time there was a huge dinosaur find here in America, it played a big part in the nation accepting the theory of evolution; that said, there is still a world of meshuggeh people that don’t believe any of this. All that played into the buzz, the controversy. As the word got out, people wanted to own dinosaurs. They were status symbols, just like they are today.’ I expected a dinosaur salesman might be rather tawdry, cut in the P T Barnum mode but, although Tanjeloff is far from a subtle man, I am moved by his earnest affection for the history of his profession.

Tanjeloff confirms what Norell told me: a lot of the high-end dinosaur buyers come from Arab oil nations. I can’t help but whisper: ‘Do they know you are Jewish? Will crackpots think Jews control the dinosaurs now?’ He swats the thought away with a hand, like my grandmother did when I was a child and told I wanted to meet Santa at Macy’s. ‘I’m one of many sellers. There’s over 100 of us that have real sales, all sorts. And we are talking about rabid collectors. When someone really wants something, anything is kosher, even for Sheiks.’

The contrast between the beauty of the gems in Tanjeloff’s basement and the lifeless brown bones scattered around them drags me back to the enquiry that brought me here in the first place: what pumps the heart of the collector? Power and money cannot explain it all. Tanjeloff lifts a framed Newsweek article from the wall, headlined: ‘New Craze for Old Bones’. ‘That was me in December of 1989, when I still had lots of hair.’ New dinosaur discoveries, and the idea that they were killed by an asteroid, sparked new interest during the 1980s.

But the real craze hit in 1990s. Tanjeloff sees a parallel between the dinosaur obsession when the movie Jurassic Park came out in the summer of 1993 and the collecting mania in 1854 caused by British sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins after he exhibited his giant concrete replicas of prehistoric reptiles on the grounds of Crystal Palace Park in London. ‘Boom! You can’t imagine, Jurassic Park did extraordinary things for every level of buyer.’ The film’s director Steven Spielberg got the average person visualising things that previously only the most diehard science boys obsessed about, like what if humans lived with dinosaurs together?

‘Sometimes people have to be reminded that dinosaurs are not in danger of going extinct, you know? They already are’

Some of that mystique lives on. Even more, though, it might be the mystique of money that drives the most extreme fossil sales. At the very high end, dinosaurs are hard to sell, Tanjeloff tells me, but when you manage to unload one, it goes to the millions of dollars.

These days, Tanjeloff mostly buys and sells fossils dug out of private property – and makes no apologies. He also sources fossils directly from palaeontologists and geologists, other fossil dealers, and from old collections. ‘Sometimes people have to be reminded that dinosaurs are not in danger of going extinct, you know? They already are. So you are not hurting any creature by selling, trading or looking for dinosaur fossils; in that way, it is also just like gem-collecting.’ On the flip side, he doesn’t peddle to US museums because ‘they are federally funded and frankly do not have much money. This is where the love affair and the need come in. They don’t have the budget to pay the top dollars that collectors want.’

Once again, the obsession of the collector and the obsession of the scientist are at odds. I mention that Norell doesn’t think much of fossils as investments. Tanjeloff gleams his teeth at me, shaking his head in disagreement: ‘Scientists don’t want to put a value on the dinosaurs; they consider them national treasures for scientific reasons. They don’t like a wealthy person taking what they think belongs to everyone to see and enjoy.’

Still, Tanjeloff tells me that most of his clients have pride in their collecting choices, and many end up donating their fossils to research. About ‘80 per cent of the time’ a buyer won’t hold on to his precious bones until the bitter end so, despite the initial swagger, it ultimately ends up in a museum or university anyway.

Dinosaur collectors are proving not as easy to classify as I’d hoped. Some people want to possess the best, it seems. Some want to be seen as generous benefactors. And despite what Norell told me, I’m realising that old-fashioned market speculation is another distinct motivation. ‘My dinosaurs don’t have quarterly reviews, but look at the last 30 years – what you could have bought back then, and what it would cost you now! Even with inflation, the compound is astronomical,’ Tanjeloff says. ‘And the numbers today are staggering. There are people spending way more than James Cameron. Some of my best dinosaur clients have very, very large homes.’

As I wrap up my visit to the Astro Gallery of Gems, my host ponders a jawbone sitting in his inbox and offers another theory. ‘I strongly believe that this is just the beginning of a craze. I think because the world is so techy, and we all live behind screens, that people are really going back to nature. I sell thousands of little fossils a week. We had a section called Astro Kids in the old FAO Schwartz toy store, and when they re-launch next year we’ll be back. Boys who love dinosaurs, they’re our future customers for the bigger sales.’

A few evenings later, in the elevator of my apartment building, a shy 10-year-old neighbour named Sebastian Koko is holding two dinosaur books tight. I desperately want to get his uncontaminated perspective: here is the collector of the future, someone who is not yet thinking about profit margins or smuggling laws. I get his mother’s permission for an interview, and we schedule a talk that evening, right after his homework is finished.

‘If I look at a toy giganotosaurus, it feels the same as looking at a real giganotosaurus. My toy is just as big in my mind’

‘I’m just starting out as a collector,’ Sebastian begins. ‘I only own prehistoric shark teeth and I have a fossil of a prehistoric squid from way before the dinosaurs, and I got a Utahraptor bone shard I think from my kindergarten teacher, she’s an amateur palaeontologist who first got me into dinosaurs, and I have dinosaur poop but I think you should put in the word “coprolite”. That’s the technical term.’ He thinks some more. ‘Oh, I have mosasaur teeth, that’s a very cool prehistoric aquatic reptile. Imagine owning a T rex though! I would like to own any complete dinosaur, I don’t care which one.’

To my surprise, Sebastian doesn’t see an emotional difference between owning dinosaur toys and owning real dinosaurs, and he hints at a dimensionless state he enters using imagination. ‘If I look at a toy giganotosaurus, it feels the same as looking at a real giganotosaurus, which I have only seen once in a museum. I really see the same thing when I’m looking at my toy. I forget that the real dinosaur is way bigger. My toy is just as big in my mind.’

Right now, Sebastian has three goals, all of which hint at the first stirrings of a collector’s ego. ‘I want to find the biggest dinosaur yet, or a new kind of dinosaur, or I’d like to discover a smaller transitional dinobird specimen. Something along the lines of archaeopteryx.’

Since I am trying to dig into the psychology of the youngest collector’s mind, I need to talk to a Freudian. I turn to 56-year-old Martin Wilner, a prominent New York psychiatrist and psychoanalytic scholar known for treating artists and collectors, many of whom collect fossils; he is also an artist himself. He is delighted to speak by phone, and admits that his dream calling as a child was to study fossils: ‘Palaeontology was my first big word!’

True to his Freudian roots, Wilner traces the dinosaur obsession to childhood. ‘Kids wonder how babies are born and how we came into being, and among the first clues are that there were things called dinosaurs that roamed the earth before we came along. If we dig into the ground we can find pieces of them, and the pieces are big. From the child’s perspective, parents and other grown-ups are akin to giants, and children are small by comparison. Now they learn that before there was Mommy and Daddy, there were these even bigger creatures that somehow led to their parents entering the picture. To make matters even more complicated, to find these dinosaurs, we dig into Mother Earth.’

I am sort of following.

Wilner continues: ‘The developmental issues associated with an early interest in dinosaurs can be usefully looked at through the prism of psychosexual stages such as the traditional oral, anal and phallic ones. It is not terribly shocking, with that in mind, to see that many dinosaur aficionados collect coprolites, fossilised dinosaur dung. Or that those collectors are particularly drawn to the giant scale of dinosaur bones.’

Just when I think I see where he is going, Wilner throws me a curve: ‘It is not an enormous stretch to see the phallic symbolism of this pursuit. There is a fetishistic narrative in the very fact that these enormous phallic forms are found buried deep inside Mother Earth, a potential balm for the castration anxiety of many developing children. It tells them that it is possible, after all, that Mommy has a phallus, only hidden away.’

I’m dubious about the castration fear, but part of Wilner’s analysis makes sense. Surely dinosaur collecting is related not only to how small we feel relative to the world, but how temporary we feel relative to the immensity of the age of the Universe. In that sense, dinosaur collectors are similar to astronomers exploring our cosmic origins. And, yes, in possessing something ancient the owner is linked to it across time.

I had really wanted a unifying theory on dinosaur collectors, but after hanging up with Wilner, I realise there is no simple explanation. The way each person engages with fossils has many facets that relate to his own developmental issues, internal conflicts, and character. Money and power can come into play. Scientific curiosity – and whatever motivation lies beneath that – can come into play, too. But for some people, perhaps, dinosaur collecting is not a trick to establish mastery of the past, whether through ownership or analysis. Rather, it seems more like a way to escape the oppressive certainty of the present. Perhaps this is the closest I will get to a definitive answer.

Then I look at my notes from my interview with Sebastian. Eureka! Scrawled in the margin of my legal pad is a quote from him: ‘Modern animals, you know what colour they are, what they feel like, exactly what they eat. Dinosaurs, you can guess away. But also, I just really like dinosaurs. I bet people who collect them think they are just as awesome.’