What follows is an account of an instance where I, a person of relatively sound mind and body, could not believe the evidence before my own eyes. It might not have been a hallucination that I experienced, but it was surely a great jolt of consciousness. The scene: I’m in my closet-sized cabin, inside a white dome built to house a crew of six for four months as part of an isolation experiment. As a crew, we are working and living as ‘explorers’ stationed on the surface of ‘Mars’. Our colony is lifelike and NASA-funded, but it is situated in a place quite a bit closer to home, on a remote slope of a Hawai’ian volcano.

It’s only a couple weeks before we are to be released, and I’m sitting on my bed with my laptop, sorting data from a sleep study I’ve been conducting on myself and my crewmates for the past three months. My cabin door is open. From the corner of my eye, I see a stranger walk into the washroom a few meters away. It’s odd, I think, for a stranger to be here. Our doors are not locked during the day, but our habitat is positioned in an isolated area, at a high elevation, far away from paved roads and pedestrians. The sight of an unfamiliar person nonchalantly using our facilities is enough to jack up my senses to high alert.

I watch as the stranger goes into the washroom and splashes water on his face. Do I know him? Why can’t I tell? If he is an intruder, why is he here? And what will he do when he’s done freshening up and sees me staring at him? I have three male crewmates and the man washing his face looks like none of them. Our crew commander shaves his head while this man has thick brown hair, slicked back. Another crewmate almost always wears buttoned-up long-sleeved shirts. The stranger is in a baggy black T-shirt. My third male crewmate is larger than the unfamiliar man and has curly red hair and a beard. This man is clean-shaven.

Finally, the stranger steps out of the bathroom and confronts me. ‘What,’ he says, less a question, more a bark. His voice kicks me to reality. It’s Simon, our red-headed engineer who has evidently shorn his beard and lost more weight over the mission than I had previously noticed.

Still, my heart is racing and a surge of blood warms me from earlobe to fingertip. ‘I didn’t know who you were,’ I say. He nods and gives a slight smile. We both laugh uneasily at the absurd thought of an intruder. It’s almost too impossible for us to imagine.

And it was shortly thereafter, as the tail end of my terror entwined with the emergent joy of relief, that I notice I hadn’t felt anything so strongly in months. I had been living in a kind of torpor. I had believed myself to be quite busy and occupied with important tasks during our time on Mars but, somewhere along the way, mental fatigue had become my baseline state. I was loathe to admit it at the time, because it implied a poor personality match with adventurers and those of the explorer class in which my crew and I – acting earnestly as astronaut stand-ins – saw ourselves. Yet, in retrospect, there is no escaping it: I was bored and had been bored for quite some time.

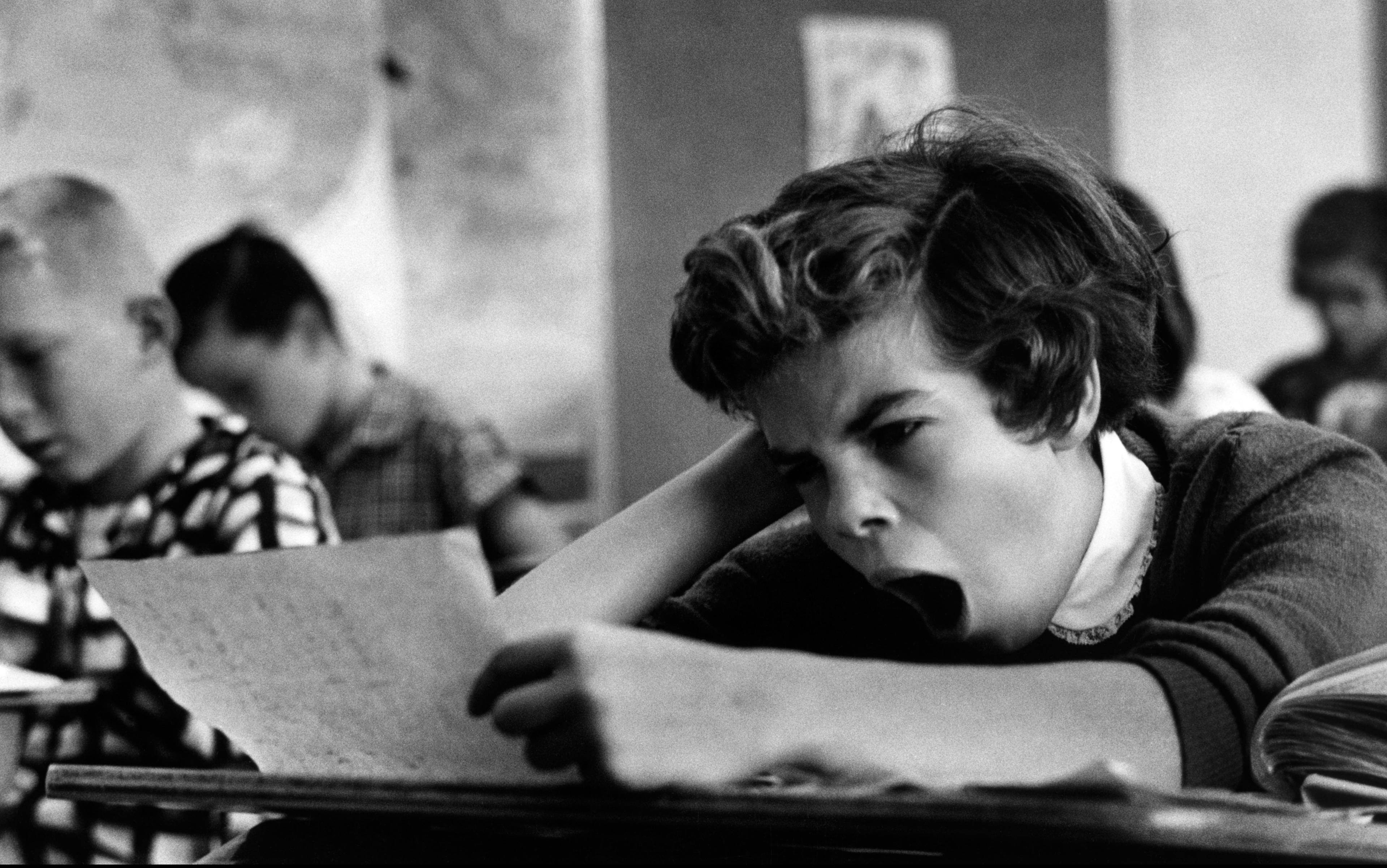

What kind of person gets bored? Only a boring one, ha-ha. Or, children who have piles of toys but no motivation to play. Also teenagers, who now use Twitter as a megaphone to fascinate (or bore) the rest of us with short descriptions of educational ennui. But to be bored as an adult? Perhaps you aren’t as busy with family and work as you should be. Hasn’t technology obliterated our opportunities for boredom? Don’t we reach for our phones at the first itch of idleness, to check in on the Facebook feed, thumb through work email, or text a funny observation to a friend? Conventional wisdom tells us that an adult with enough downtime to be bored has surely taken a wrong turn in life.

There are exceptions, of course. It is acceptable for you, an adult, to be bored with certain tasks, or with your career, or even your life. You can decry the fact that your days blend into weeks, and weeks into months, Wednesday barely distinguishable from October and so on. Maybe you are more bored than ever when you watch movies and television, read books and have conversations. You can even become bored scrolling through never-ending and inane Facebook updates, or an infinite Twitter feed of predictable headlines, celebrity photos, and the master-crafted self-promotion of your peers.

But suppose you never get bored. Suppose you can honestly say you are fully engaged and interested, almost always, in life and its offerings. You might find comfort in all of this busyness, but science has some bad news for you. Recent psychology research suggests boredom is good for you. It can lead to prosocial activities such as donating time or money to charity. And the daydreaming it prompts can produce insights and spur creativity, enabling happiness you didn’t know you were missing.

Now, say you are often bored. Maybe you’d rather not be bored or maybe you don’t care, but either way, you simply cannot avoid it. Bad news for you, too. Psychological studies have concluded that boredom leads to accidents and poor performance at work, to substance abuse, to overeating and binge-eating, and even to heart attacks.

has boredom become the psychological equivalent of a glass of red wine, to be enjoyed, guilt-free, only in moderation?

So what is it, then? Is boredom bad or good? Should we do our best, for the sake of our health and employment, to avoid it? Or has boredom become the psychological equivalent of a glass of red wine, to be enjoyed, guilt-free, only in moderation? Is the moderation of boredom desirable or even possible? How many successive rhetorical questions does it take to bore a reader? No one knows.

According to the contemporary Norwegian philosopher Lars Svendsen, the concept of boredom as we understand it today is distinctly modern. In A Philosophy of Boredom (2005), Svendsen notes that while it’s ‘always possible to find earlier texts that seem to anticipate the later phenomenon… boredom is not thematised to any major extent before the Romantic era’. It was during that time, he writes, that the concept became democratised, and not solely ‘a marginal phenomenon reserved for monks and the nobility’. ‘Boredom is the “privilege” of modern man,’ he adds.

And so here we are. Whether you believe we are experiencing peak ‘boredom privilege’ or whether you believe that a life well lived simply offers no time for boredom, most people agree: boredom itself is interesting. If only we knew what it actually was.

You might have a sense of what boredom feels like to you, but it’s the very subjective nature of boredom that makes it difficult to agree on a single definition.

Psychologists believe, broadly, that boredom can be divided into two major categories: situational boredom and existential boredom. Situational boredom is the kind that arises when an environment or situation doesn’t hold our interest, like staring at an uneventful radar screen for an hour. Existential boredom extends beyond discrete situations. It wraps itself, like a wet woollen blanket, around every aspect of life, so that a sufferer lives a life devoid of satisfaction.

The German psychiatrist Martin Doehlemann identifies two categories of boredom beyond situational and existential. These are a boredom of satiety, when one gets too much of something so that it loses its meaning, and a creative boredom, which is characterised by the way it compels a person to try something new.

But that’s not all. It seems there might also be five other boredom categories, wholly distinct from Doehlemann’s, as derived by the German psychologist Thomas Göetz. In 2006, Goetz outlined four categories of boredom based on questionnaires. And last year he announced the surprise discovery of an unexpected fifth type of boredom.

Boredom, then, is a multifaceted jewel with a glint dependent on ambient light. One of the great paradoxes of boredom is that it often plagues those in the most exciting of professions: explorers, astronauts, pilots, firefighters, sailors, and soldiers. In these fields, boredom is considered a real danger, because long periods of downtime must be endured between bursts of alertness and adventure.

Perhaps nothing is more boredom-producing than the monotony, idleness, and sensory deprivation endured when stranded for months on an ice floe in the Antarctic awaiting rescue. Such was the fate of the adventure-seeking crew of the Endurance, Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated 1914 attempt to reach the South Pole.

In his diary, the first officer Lionel Greenstreet wrote:

Day passes day with very little or nothing to relieve the monotony. We take constitutionals round and round the floe but no one can go further as we are to all intents and purposes on an island. There is practically nothing fresh to read and nothing to talk about, all topics being absolutely exhausted… I never know what day of the week it is except when it is Sunday as we have Adélie liver and bacon for lunch and [it] is the great meal of the week and soon I shall not be able to know Sunday as our bacon will soon be finished. The pack around looks very much as it did four or five months ago…

Around the same time that Greenstreet complains of monotony, one of the expedition’s surgeons, Dr Alexander H Macklin, writes on idleness:

I am absolutely obsessed with the idea of escaping… We have been over 4 months on the floe – a time of absolute and utter inutility to anyone. There is absolutely nothing to do but kill time as best one may. Even at home, with theatres and all sorts of amusements, changes of scene and people, four months idleness would be tedious: One can then imagine how much worse it is for us. One looks forward to meals, not for what one will get, but as definite breaks in the day. All around us we have day after day the same unbroken whiteness, unrelieved by anything at all.

More recently, in November 2011, the British explorer Felicity Aston embarked on a solo journey across Antarctica, skiing for a total of 59 days. The secret of her motivation, she told the website Travelbite in 2012, was the simple act of following a routine, as well as a mix of more than 800 music tracks – although, by the end of it she was, she said, ‘bored with pretty much all of them’.

Aston also described a visual monotony and social isolation she experienced while skiing that seemed maddening:

Because I had no one else to talk to I found that I started talking to the sun (as it was the only different thing in the landscape!), as if it was a friend accompanying me on the trip. Sometimes the sun would even answer back, asking why I was doing such a silly thing!

It’s conditions such as these – monotony, idleness, tedium, sensory deprivation, loneliness – that concern NASA psychologists who want to send a crew to Mars. Using existing technologies, a trip to the red planet will take 200 to 300 days of travel. Most of the time will be spent inside a cramped capsule. There will be a communication delay with Earth of up to 20 minutes due to a yawning gap of tens of millions of miles. Real-time chatting or video calls with friends and family and mission support will be impossible.

Mars crews would likely need to operate with a high level of autonomy because of this communication delay. Many people believe autonomy, which implies freedom of choice, can stave off boredom. Indeed, work imbued with personal meaning can be a potential salve, but it can’t fix everything. In addition to the isolation and sensory deprivation, there will still be repetition of meals and routines and clothing and conversations between crewmembers. The workloads will still likely be full of tedium with narrow margins for error. In short, a mission to Mars has the perfect ingredient list for boredom and disaster borne of boredom.

Crewmembers aboard Antarctic exploring vessels need to climb masts, secure lines, and so on. And even if they’re not involved in these activities, they likely at least feel the sensation of wind against their bodies and wood and ice underfoot, all tangible reminders of the passing of time and the harshness and dangers of the environment. Mars explorers, in contrast, would live in a much smaller ship with far fewer sensory inputs. Technology, from propulsion systems to plumbing, would lay hidden behind panels, displays, and buttons. Time will more easily blur and dangers will be more difficult to sense.

To bored crewmembers, a system failure might present as an alarm clock trying to rouse a person from sleep

When Shackleton’s Endurance was trapped in ice, the crew could hear the creaking, whining, and eventual explosions of the wooden hull, leaving no doubt to the seriousness of their situation. On a Mars-bound ship, danger might creep into crew consciousness with a blinking light or a beeping alert. To bored crewmembers, a system failure might present itself as something like an alarm clock feebly trying to rouse a person from the haze of sleep.

On the International Space Station, 250 miles above the planet’s surface, astronauts spend much of their leisure time gazing at and photographing Earth. As a Mars-bound ship drifts millions of miles from home, this major source of interest and connection to humanity will recede into the void.

A trip to Mars, with its invisible technology and vast, unprecedented distance from home, could estrange or alienate a crew to an unprecedented degree. Such a distance could produce an entirely new kind of boredom, impossible to imagine on Earth.

Or, it might not be so bad. In addition to selecting astronauts with sound minds, providing the crew with careful and considerate mission support, and enabling crew autonomy in work and leisure (such as with games and films), another way psychologists suppose NASA could beat boredom could be through interior design. One suggestion has been to include a periscope inside a Mars-bound ship that could magnify an image of Earth for gazing. Another is to include a system that projects Earth images onto a screen, or a kind of holodeck, like the one from the 1980s TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation.

It could also be important for mission support to remind the crew, often and in varying ways, about the importance of the goal, for all humanity, of exploring Mars. The 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote in his essay On the Vanity of Existence (1851), ‘as things are, we take no pleasure in existence except when we are striving after something’. This would seem to be especially true for high-achieving people such as those traditionally selected as astronauts.

Some creative people claim that there are generative benefits that come from spending time in a state of low arousal and monotony, as though boredom primes their minds to receive new ideas and connections. Siegfried Kracauer, the 20th-century German writer and critic, wrote an essay called Boredom (1924), in which he argues its virtues and claims:

If… one has the patience, the sort of patience specific to legitimate boredom, then one experiences a kind of bliss that is almost unearthly. A landscape appears in which colourful peacocks strut about and images of people suffused with soul come into view. And look – your own soul is likewise swelling, and in ecstasy you name what you have always lacked: the great passion. Were this passion – which shimmers like a comet – to descend, were it to envelop you, the others, and the world – oh, then boredom would come to an end, and everything that exists would be…

This sentiment accompanied David Foster Wallace while he was writing The Pale King (2011), a novel about IRS employees and boredom, published after his suicide in 2008. In a note accompanying the manuscript, Wallace wrote:

Bliss – a second-by-second joy and gratitude at the gift of being alive, conscious – lies on the other side of crushing, crushing boredom… Pay close attention to the most tedious thing you can find (Tax Returns, Televised Golf) and, in waves, a boredom like you’ve never known will wash over you and just about kill you. Ride these out, and it’s like stepping back from black and white into colour. Like water after days in the desert. Instant bliss in every atom.

This bliss is just the sort of thing that might launch a creative project or spur a major life change, for better or worse. Perhaps it was boredom, coupled with the remnants of my childhood dream of being an astronaut that prompted me to apply to the four-month isolation experiment to simulate a Mars mission. And, in full circle-fashion, that’s where I finally came to know my own particular flavour of boredom and how it manifests in me.

The Mars project, called HI-SEAS (Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation), was designed to investigate a particular type of boredom called menu fatigue or food boredom. Because food is crucial to energy, health, and morale, and because astronauts tend to tire of the same pre-packaged meals and eat fewer calories, NASA funded the HI-SEAS project to see whether it might be better to let a crew cook some meals for themselves once they regained gravity on the Martian surface. The study ended last August, and the results aren’t yet in, but I suspect that the variety of food available was sufficient so that cuisine wasn’t my major source of boredom. There were other, more insidious culprits.

About halfway through the mission, the journalist Maggie Koerth-Baker emailed to ask how we were holding up, boredom-wise. She was writing a New York Times magazine piece on the topic. As a crew, we discussed it: we certainly didn’t feel bored. We always had something to do, from personal projects, to exercising, to chores and maintenance, to putting on spacesuit simulacrums to venture outside, to writing reports and summaries of our activities, to filling out the numerous, sometimes lengthy, daily surveys and writing journal entries.

In fact, we felt like we couldn’t quite catch up. A good night’s sleep proved difficult for most of us; you could often hear at least one person tapping away on a keyboard well past midnight. In retrospect, our leisure time was quite minimal. Two nights a week we watched a movie that, while scheduled and enjoyed, often felt a little forced. Sundays were mostly free days, although surveys and meal reports were still required, and many of us used that day to catch up on lingering work obligations. We did, however, celebrate monthly milestones and birthdays with specially prepared food and music.

With some distance from the project, I see now that it had its own brand of monotony that began to wear us down. Some of us didn’t go outside much. Putting the suits on was a hassle and it seemed to detract from personal projects, most of which were done indoors. We kept the same daily schedule for exercise, meals, chores, and work; we sat in the same seats around our table; we answered the same survey questions day after day; we wore the same few outfits week after week. The dome, while beautifully designed, was covered in white vinyl that none of us modified with paint, fabric, pictures or posters. We began to joke about our ‘puffy white walls’, and an institutionalised life.

Of course, we all found ways to distract and entertain ourselves. I, for instance, juggled tennis balls, batted around balloons, and tried, without success, to play the ukulele. I also read a good number of books and articles, and spent time writing and listening to podcasts and music. One crewmate took up night photography, a satisfying and ever-evolving challenge. Another crewmate staggered her research projects throughout the mission so she would have a new one to look forward to every couple of weeks. Others played video games and listened to music.

a crewmember joked, with a wild look in his eye, that he imagined ripping through the habitat cover and going for a walk, sans spacesuit

It’s easy to see how we believed we weren’t bored at the time, especially since we all knew the negative association boredom has for astronauts and explorers. We did begin to feel restless at the end, though. At the time, one crewmember joked, with a wild look in his eye, that he imagined ripping through the habitat cover and finally going for a walk, sans spacesuit.

Before Mars, I had always assumed I wasn’t the type to get bored. I was never compelled to call anything boring, no matter how monotonous; it seemed like a simplistic dismissal. After all, life was far too interesting for that. But after the shock I felt that fateful day when our engineer masqueraded as a beardless stranger outside my room, I started to take boredom more seriously. The extreme contrast between an emotional height and my previously muted state let me see my own version of boredom for what it was.

And indeed, I had experienced it before. After doing some reading around on the topic, I discovered that certain behaviours – imagining oneself in the future, making new plans, learning new skills, setting goals, trying to refresh and start anew – are typical of someone who feels bored. I could check all of these off. For as long as I can remember, I’ve responded to an ill-defined niggling inside that propels me to try new things.

I was often inspired to try new things on Mars, whether it was new kinds of writing, sketching, or picking up an instrument. And there was absolutely a point in the mission when all I could do was think about future plans: my wife and I signing up for a timeshare yurt with friends, for instance, or travelling to Puerto Rico, or writing a new book. Some of these imaginings certainly bordered on bliss. All this felt familiar, somehow. Might I actually suffer from chronic boredom and not even know it?

My time on Mars showed me the light and dark side of boredom. My creative side relished the opportunity for a quiet mind that could seek out new tasks and get lost in an imaginary futures. But the wannabe astronaut in me worried that boredom lowered my interest in certain necessary and repetitive tasks and led to needless ennui. If only boredom could be compartmentalised. And I wonder now if that’s what all this talk about missions to Mars is about. Our astronauts and explorers act as collective bearers of boredom as we search for new worlds and experiences.