‘Gods change up in heaven, gods get replaced, prayers are here to stay.’ So wrote the late Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. Anyone not sharing his conviction might consider a visit to the Blue Lotus Buddhist temple in Woodstock, Illinois. There, in a converted church, worshippers take their places between a massive new statue of the Buddha and the original stained-glass Christ, solicitous of his sheep. A series of actions takes place that could be focused on either image: a bell rings, the people stand, the clergy enter, and everyone bows in reverence. Then the work of prayer and meditation begins. The people chant their desire to take refuge in the Buddha and set themselves to focus on loving kindness.

Prayer is a concept that baffles and beguiles. It eludes definition, comprehending wildly disparate and even contradictory practices. It includes humane self-fashioning and bitter imprecation, strict formality and total improvisation, wordless meditation and lengthy monologue, the intention prolonged in a spun wheel or a lit candle. And to the extent that prayer is not now, and perhaps never has been, understood as a way to cajole and influence the power that governs the world, it is not always obvious what prayer is supposed to accomplish.

As anyone who has successfully abandoned a regular prayer practice can say, it isn’t hard to get by without. Yet this particular gathering and focusing of consciousness must be doing something. Prayer is religion’s hermit crab; it scuttles recognisably from age to age and purpose to purpose, while attempts to refute or confirm are left to grasp its shells. It endures, shaping the mind, altering the body, or reflecting and resisting the forces of modern life. In its irreducible variety and seeming gratuitousness, it remains a puzzle. But if prayer itself resists explanation, it can still be illuminating to map its dimensions.

In one of its most common and controversial forms, it takes the form of a petition made to the almighty for, well, all kinds of purposes, public and private, physical and spiritual. Public intercessory prayer has been a consistent feature of Christianity since its early days. Registers were kept of clergy, civil leaders and people in need, and intercession was made for them in the community’s worship. Common practices included anointing the sick and praying for healing. Over time, the anointing ritual was formalised as extreme unction and largely confined to moments of final illness. Intercession, however, lived on.

Put into theological terms, intercessory prayer was an appeal for God’s ‘special providence’ – an exceptional intervention beyond the ‘general providence’ that governed natural processes. Doubts and dissents on that principle were common, but they did not contaminate public worship, which dutifully pleaded for the health of rulers and bishops (always by their first names).

The 19th-century statistician Francis Galton, writing with an almost roguish scrupulousness, decided to test the efficacy of such prayers with a statistical study of the longevity of British royalty, clergy and other elite groups. He found that members of royal families – the most interceded-for class of people in Britain – had a shorter average span of life than other, less prayer-lavished cohorts. ‘The sovereigns are literally the shortest lived of all who have the advantage of affluence,’ Galton concluded in 1872. ‘The prayer has therefore no efficacy, unless the very questionable hypothesis be raised, that the conditions of royal life may naturally be yet more fatal, and that their influence is partly, though incompletely, neutralised by the effects of public prayers.’ Clergy fared a bit better, but not much, and Galton explains their relative longevity by their ‘easy country life and family repose’.

Galton’s analysis, preliminary and uncontrolled though it was, marks a turn away from understanding prayer as an appeal to the indulgence of a not-wholly-predictable deity and toward something more like alternative medicine. ‘Special providence’ is a concept in long discursive decline, overtaken by the ‘power of prayer’. This is an imprecise yet curiously objective replacement, more suited to the study of a national church with standard forms of intercession than the endless plurality of forms and intentions available today. A major 2006 study led by Harvard nevertheless used standardised intercessions and control groups to isolate a treatment effect of prayer (practised, to avoid additional confounding factors, by three different religious communities). It didn’t find one.

‘I’ll be praying for you’ is a phrase that falls between ‘I am thinking of you’ and ‘I will drop off a casserole’

Such studies suggest a practice trapped by modern metaphors shared by both skeptics and believers. Prayer is analogous to a drug. Its workings are no longer looked for in the ecstatic interruption of natural processes or inevitable chains of causes, but within them as a focused concentration of psychic energy producing, or failing to produce, some discernible and reliable effect. Christian communities that emphasise the power of prayer describe it as a ‘force’ that can be harnessed and directed with greater or lesser efficacy, depending on the practices and dispositions of the person trying to wield it. Intercession for some human need is not simply ‘faith healing’ or a superstitious rejection of scientific thought, but rather a practice that runs parallel to it.

But alternative medicine is not the only way contemporary practitioners use intercessory prayer. The cost of time and effort in a capitalist economy can make intercessory prayer into something like donated labour. ‘Somebody prayed for me, had me on their mind / Took the time to pray for me,’ a Gospel song goes, rather gently raising the topic of prayer’s opportunity cost. ‘I’ll be praying for you’ is a phrase that falls between ‘I am thinking of you’ and ‘I will drop off a casserole.’ It affirms a social bond – benevolent intentions embodied in words and mediated by a shared belief in a God who, if nothing else, will note the exchange.

In a poignant and earnest essay, Nicole Cliffe, Editor of the culture and humour site The Toast and a recent convert to Christianity, describes her newly adopted prayer practice. She starts with the Lord’s Prayer (‘a little incantation that places a barrier between me watching Brooklyn Nine‑Nine and me engaging in a searching moral inventory of my life’) and continues by praying for colleagues, members of her online community, ‘people who are sick, or who have sick boyfriends, and I pray for bigger world stuff, and by the time I’m done, I’ve realised that I love all these people I’ve prayed for’.

In the fragmented and often anonymously hostile environs of online culture, prayer creates an imagined community, engendering love for those held in conscious intention night after night.

Of course, not all, or even most, practices to which the term ‘prayer’ is applied require the creative, expressive cognition of intercession. Islamic salat, the five-times-daily prayer obligation, is highly structured and choreographed. Like the daily office of Christian monasticism, it is a textual recitation stretched across the hours. Here is something more akin to a sacrifice than a conversation. One early source, the Kitab al-Salat, is greatly concerned with the timing of the act and much less with its subjective context and emotive purpose. ‘If anyone performs ablution for them well, offers them at their (right) time, and observes perfectly their bowing and submissiveness in them, it is the guarantee of Allah that He will pardon him,’ the Kitab records; ‘if anyone does not do so, there is no guarantee for him on the part of Allah.’

Nevertheless, the hard objectivity of ritual prayer cultivates a detachment from the world of practical needs that it interrupts and structures. So, perhaps inevitably, it drifts into a role of resistance and opposition in a world of purely homogenous and instrumental time. The clock can indicate precisely when the offering is made and what it interrupts. In 2001, 30 Muslim workers resigned from a chicken-processing plant in Georgia because their employer would not allow them to take a five-minute prayer break at the same time, insisting that to accommodate their prayer needs would require shutting down the processing line. In a 2013 paper summarising interviews on the workplace praying of Belgian Muslims, Nadia Fadil, a sociologist at the University of Leuven, identified one attitude toward prayer in a European context as resistance to ‘prioritising the demands of the mundane’. A Muslim student told me that when she won’t be home for a prescribed prayer time, she performs ablutions in a gas station and prays in her car. The ritual redraws the boundary between the sacred and the ordinary.

Worshippers frequently and variously accommodate highly structured prayer practices to unyielding circumstances. But when they don’t, the juxtaposition and conflict are vivid. Ethiopia’s ‘Salat Man’, who in 2013 prayed while surrounded by riot police in Addis Ababa, became a symbol of the conflict between the country’s Muslim minority and the government. The throngs of worshippers prostrating themselves in Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011 reproduced the conflict between the pious and the civil authority on a massive scale. The power and legitimacy of a secular state shrank when contrasted with a communal ritual that is pitched, literally, beyond time and space.

So prayer is multifarious. It can aim to shift the world’s netting of causes and effects, to strengthen communal bonds, even to resist an economic and political order. But perhaps its most venerable function is to shape the moral disposition of the worshipper. In the Christian monastic tradition, the ongoing rhythm of prayer was practiced not merely for its objective necessity or its symbolic meanings but, as the religion scholar Talal Asad at the City University of New York has argued, ‘in order to make the self approximate more and more to a pre-defined model of excellence’. And as it happens, while the ‘power of prayer’ to change outcomes in the world has been hard to identify scientifically, its effects on the one who prays have in recent years been much easier to find.

Prayer in general and meditation more specifically have become highly touted as aids to mood, memory and anxiety. Repetitive, meditative prayers such as the Catholic rosary or Buddhist mantras ‘have been shown to have a distinct, powerful, and synchronous effect on the cardiovascular rhythms of practitioners’, report Andrew Newberg and Mark Robert Waldman in How God Changes Your Brain (2009). The authors studied a specific course of meditative practice involving 12 daily minutes of breath, chant and finger motions. They found that subjects experienced significantly higher activity in the anterior cingulate, without having any subjective belief in the worldview of which the meditative practice is a part. Those findings were consistent with studies of full-time contemplatives, Buddhist and Christian, who experience dramatic patterns of brain activity when they meditate or pray.

Spiritual practices are techniques for gaining control over our body, our mind, our fate

Where the ‘power of prayer’ pragmatism in modern Evangelical piety makes prayer into a sort of alternative medicine, the zeal of the neuroscientists for meditative practices gives it the character of therapy or self-help. Unlike the deep theologies that shaped the prayer and meditation practices they studied, Newberg and Waldman are agnostic on the question of whether those practices touch a mind or a reality outside of the practitioner. They are ecumenical in their evaluation of the value of those practices, and more or less indifferent to the purposes toward which they are deployed. Spiritual practices are techniques for gaining control over our body, our mind, our fate. The brain is ground enough to validate the experience, and it is wondrously malleable. The authors even suspect, though they don’t exactly demonstrate, that ‘fear-based religions’ can lead to something like post-traumatic stress disorder in their practitioners. In modern, scientifically-validated prayer practices, we choose our ends. In ancient and medieval models, our ends chose us.

The most intriguing finding in the neuroscience of prayer might be that practices can shape our understanding of God. As Amichai puts it in a moment of naively phrased heresy:

I declare with perfect faith

that prayer preceded God.

Prayer created God,

God created human beings,

human beings create prayers

that create the God that creates human beings.

The prayer and the God toward which it is directed shape each other in a feedback loop. ‘Religion creates a template for spiritual practice, and spiritual experiences alter one’s conception of religion,’ as Newborn and Waldman put it. But ‘religion’ is not itself a static template. It comes to us as a product of practices endlessly repeated, shaped by the uses, needs and circumstances for which the practices have been kept.

These acts of the mind command respect out of proportion to any of their demonstrable effects. Interrupting a monk in the midst of meditation is not like striking up a conversation with a man on a park bench. The sight of thousands bowed down in Tahrir Square is not like a similar number standing and shouting slogans. There might be a bashfulness inherent in observing consciousness in such a pure and focused form, the chaste elder sister of all thoughts. To ask whether prayer changes the world is, inescapably, to ask whether any of those other thoughts do, too.

Soon after the meditation service at the Blue Lotus temple began, I found myself in unfamiliar liturgical seas. The God of my prayer is, I would guess, very similar to Cliffe’s – sociable, benevolent, approachable, even while clothed in awe. He is also a bit professorial, latent in the texts I chant, recite or read each morning at my desk before I begin my tasks. But with the Buddhists, I was invited to refrain from the considerable cognitive effort I take in speaking to this God.

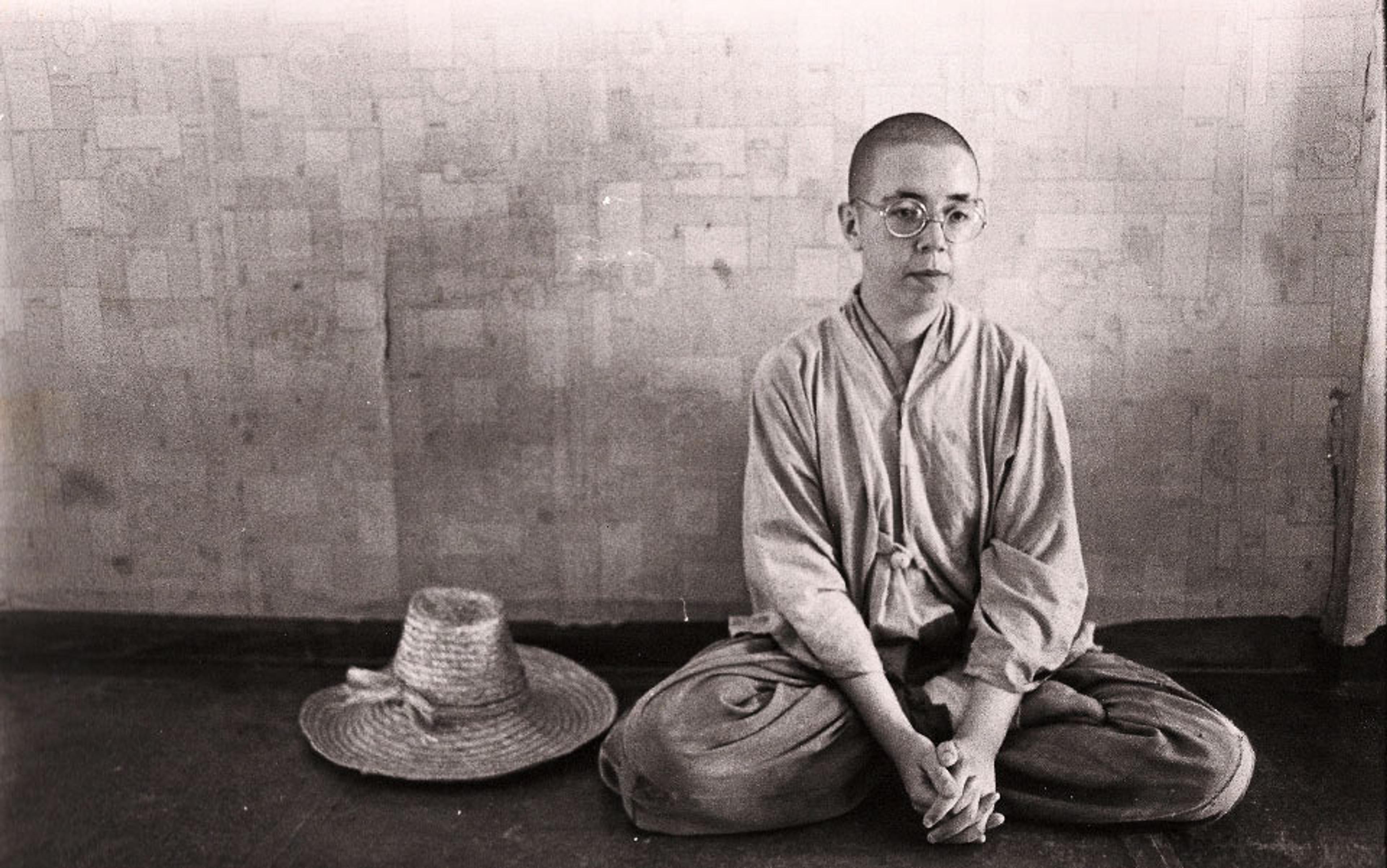

Christian prayer has, of course, belonged to the realm of cognition since at least the time of Thomas Aquinas. So it felt a bit subversive to let my intentions vanish as soon as they arose. It was liberating, too, for someone shaped in a faith heavy-laden with words and desires awaiting purification and a world demanding that I perpetually attend to a thousand priorities. It didn’t help my memory or my social awareness – eight weeks of daily practice are needed for that, according to the research. But it did nudge my picture of God – my religious template – into a slightly different shape. ‘We’re becoming an observer,’ Bhikkhuni Vimala, a nun at the temple told me. And so I was, for a moment anyway, between Buddha and Jesus, watching my words and thoughts hurtle, not toward God, but in the opposite direction. Then familiarity returned with the chanting of ancient texts, and the moment passed.