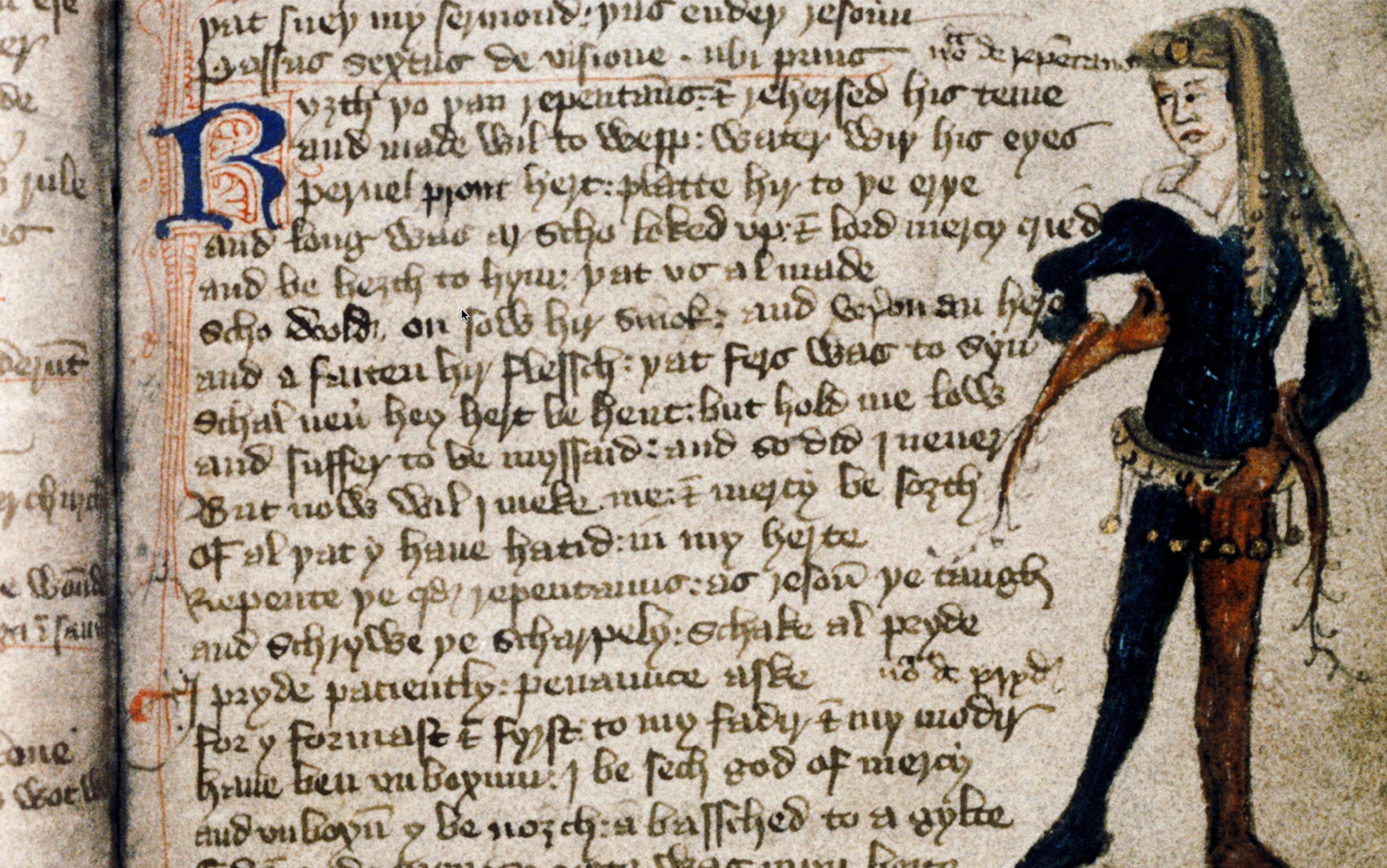

Lexicographers are persistent creatures. Never content, they scour each newly published edition of a hitherto unprinted text for antedatings, or a sighting of a word in the wild that predates the current first citation in the dictionary. Last year, their diligence provided a new entry in the Middle English Dictionary for the word ‘gibberish’ that, though once thought to be an invention of the mid-16th century, actually makes its first appearance around 1450. A religious guide to vices and virtues warns its readers that to mutter prayers inattentively or without proper piety is to utter ‘giberisshe too Godde’ (talk gibberish to God). The writer assumes that gibberish is equivalent to foolishness and insincerity. But what should we think about this strange part of human language-making?

Though its arrival in English has been redated, the etymological origins of ‘gibberish’ remain a little mysterious. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) popularised a folk-etymology connecting ‘gibberish’ with ‘chymical cant’, technical terms of alchemy and science as used by ‘Geber’, the Westernised name of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, not so much one author but an identity to which much medieval Arabic scholarship was attributed. The truth is much more ordinary: ‘gibberish’ probably comes from ‘gibber’, one of a clutch of verbs such as ‘gobble’, ‘gabber’, ‘jabber’ and ‘gab’ that onomatopoeically imitate the sound of unintelligible babbling. However, the first instance of ‘gibber’ – in William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet where the ‘sheeted dead’, corpses risen from their graves, are imagined to ‘squeak and gibber’ ominously in the streets of Rome – comes much later than ‘gibberish’.

Gibberish – language that cannot be understood – is not quite the same as nonsense. In nonsense writing, we read individual words but can’t parse them into any meaning that makes sense according to conventional expectations. ‘Colourless green ideas sleep furiously,’ as Noam Chomsky put it in Syntactic Structures (1957), in an example of a semantically meaningless sentence with syntax present and correct. Gibberish, on the other hand, makes indecipherable words out of the sounds and letters of language. The giant Nimrod, who, according to patristic tradition, commanded the building of the Tower of Babel and thus shattered humanity’s single language into all of the tongues of the world, is punished with unintelligibility in the Inferno of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (1308-20). Guarding the Ninth Circle of hell, Nimrod calls out: ‘Raphèl maì amècche zabì almi.’ Ignore him, says Virgil, his guide, for he cannot understand us, just as we cannot comprehend his words.

Nimrod’s strange phrase is properly gibberish, letters made into words whose individual meanings escape us, however much scholars puzzle and hypothesise. Yet gibberish does most of its cultural work as a wildly inaccurate label. Speech accused of being gibberish is almost always not gibberish but fully functioning language: we take intelligible utterances and turn them into gobbledygook by refusing to recognise or interpret them. For centuries, one nation has sneered at the speakers of another nation’s tongue, belittling the language of others as ‘barbarian’ (from the Greek βάρβαρος, ‘barbaros’, a word said to imitate animalistic baa sounds, how the Greeks supposedly perceived the speech of non-Greek speakers). Nowadays, we dismiss the complicated technical talk of experts as ‘gibberish’ because we find their terms and expertise intimidating or threatening. Arguments we don’t like are ‘gobbledygook’ or ‘word salad’, not because we can’t understand them but because we refuse their logic. (‘Word salad’, by the way, is a transliteration of the German Wortsalat, originally a medical term for the muddled-up speech of people with schizophrenia.)

The term ‘gibberish’ is mostly imposed unfairly on others, a quick-and-easy way to express prejudice and to downplay the language of others as mere noise. Gibberish is, however, sometimes created voluntarily for benign purposes and this too has a long history. Some Old English medical charms, preserved in a manuscript written around the year 1000 CE, have passages of gibberish mixed up with words from Old Irish, Latin, Greek or Hebrew. These unintelligible words have defied attempts to untangle their meaning or etymology, and so the scholarly consensus is that they form a placebo, like the magic words that accompany a spell. Just as a fancy Latinate or Greekish-sounding name on a modern packet of pills might make us feel more confident of a cure, so these sounds and syllables that refuse to match up to anything recognisable in Old English or any other language might have persuaded those who heard them that this charm was sure to work.

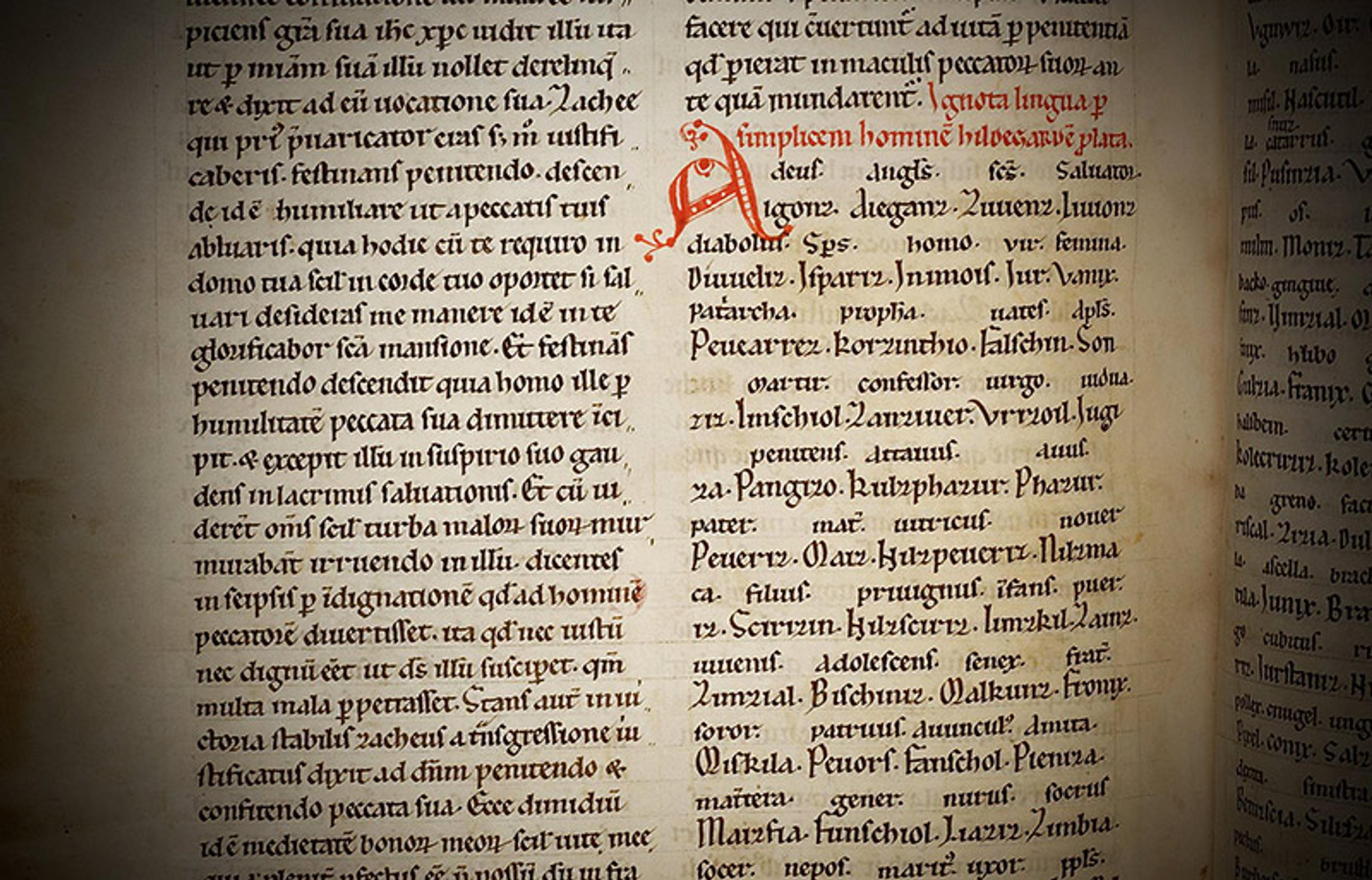

Gibberish syllables are also used to build invented or fictional languages. Many of these ‘conlangs’ (a portmanteau word smushing together ‘constructed’ and ‘language’) are carefully developed as artificial languages, but some invented tongues never gain all their working parts and thus remain essentially gibberish. Paired with a translation, they might seem to be a language but, without their glosses propping them up, they only ever pretend to have meaning. The 12th-century German abbess Hildegard of Bingen, composer, philosopher and mystic, devised a lingua ignota, an ‘unknown language’ preserved in a list of 1,012 of these unknown words with a Latin or German gloss, and also in a short hymn written mostly in Latin but studded with gibberish that glitters like jewels: orzchis, caldemia, loifolum, crizanta, chorzta.

Hildegard of Bingen’s ‘lingua ignota’ from the Wiesbaden Codex. Courtesy Hochschule Rhein/Main.

The sort of scholars who can’t bear a void or a known unknown have sought out etymologies – perhaps you too are now trying to puzzle them out from the languages you know – but their explanations are speculative and don’t decipher very many of Hildegard’s words. Others have wondered if these unknown words try to recreate the language in which God spoke to Adam in Eden, or the language in which Adam named the animals. Yet as the German-language scholar Jonathan P Green at the University of North Dakota points out, would such divine or Adamic languages really need words for ‘prostitutes, fornicators, magicians, drunkards, and thieves’, as Hildegard’s does? Green’s explanation is closer to home: Hildegard likely encountered words and phrases of Greek (an alphabet and language of which she had little or no understanding) embedded in scripture and in poems that mixed Greek words into Latin verse. The hymn recreates her own experience of bumping into an unknown language. What’s Greek to Hildegard is, thanks to her lingua ignota, Greek to all of us.

Thomas More’s trick is to give us the basic grammar of a language decked out in strange clothes

Hildegard’s gibberish words need their Latin and German glosses and her Latin poetry to persuade us to take them seriously as language. Likewise, on its own, the imaginary language of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) is nothing but symbols. Four lines of a Utopian poem, spoken in the voice of the island, appear as a supplement to the main text. Transliterated into our alphabet (‘Bargol he maglomi baccan’) and then translated into Latin (‘Una ego terrarum omnium’) and later English (‘I alone of all nations’), the phrases begin to convince us that they are language. At the same time, they constantly dodge the idea that they are our language. Such an invented tongue is a kind of anti-English, using letter combinations and phonology that appear only rarely in English or the other languages that More’s readers would know.

This is somewhat trickier to do in English with its mixed Germanic/French heritage and unruly spelling system. If only you could play scrabble in Utopian with its fondness for the least-loved letters and combinations of English (though someone would soon change the scoring system, I’m sure). Yet while they evade familiar spellings, they lean on our intuitive knowledge of how the English language works. These Utopian phrases have monosyllables that might be pronouns, longer words that might be verbs or nouns, and pairs of polysyllabic words that make us suspect adjectives and adverbs doing their job of qualifying. Like a skeleton in fancy dress, More’s trick is to give us the basic grammar of a language decked out in strange clothes.

The language of Utopia is an esoteric gibberish, but there are more everyday examples of unintelligible language. Once we have acquired our language as children, you would think that babbling and gibbering would cease, but there are weak points where gibberish can easily break through. Singing seems to teeter on the edge of gibberish, enticing us to switch from words to noises. When we forget the lyrics of a song, we hum and la and ooo and di-dah. Or, if there are no words, the human voice might join in as an instrument: tee-tum, taa-raa. Singing often stretches out words into their component syllables, tempting us to lose track altogether of the boundaries of words.

Jack Kerouac wrote in On the Road that ‘to Slim Gaillard the whole world was just one big ‘Orooni!’.

Linguists call these fragments of sung gibberish ‘non-lexical vocables’, sounds we can vocalise but that aren’t words in any usual sense. You might think of the scat-singing of jazz, or music such as doo-wop or bebop in which the vocables themselves provide the style’s name. In jazz, the human voice competes with other instruments in improvised sections, and it is much easier to improvise in gibberish than with real lyrics. Similarly, swaying and singing to lull a fractious baby to sleep when you are so tired you can hardly think straight creates the perfect conditions for gibberish to emerge. Words aren’t important to a pre-verbal infant: what has mattered since time immemorial is voice-made music. Medieval lullaby carols in the voice of the Virgin Mary comforting the Christ child preserve some of the earliest of these sung non-lexical vocables in English in their choruses: lulley, lollay, lay.

That word ‘lullaby’ comes from a combination of two of these early English vocables: lulla-lulla and bi-bi. A 15th-century carol scruffily preserved in a fragmentary manuscript has a chorus full of the soothing gibberish a parent might sing to a child:

Lullay, lullow, lully, lullay,

Bewy, bewy, lully, lully,

Bewy, lully, lullow, lully,

Lullay, baw baw, my barne [child],

Slepe softly now.

The sole surviving verse makes clear that this is a song sung by a ‘maydin moder’, Mary, to a sleeping ‘knaue child’, the infant Christ. Only the final phrases of the chorus are real words and the rest are vocables, words where no etymology is possible. The entries in the Middle English Dictionary for ‘bewy’ and ‘bau’ have nothing to offer about their origin. The lull- words derive from the verb ‘lullen’, itself explained as simply ‘imitative’ (though this could easily be the other way around, the vocables inventing the verb). Such words are onomatopoeic, written approximations of the ‘b-b-b’ and ‘l-l-l’ sounds that parents coo at their infants. Without conscious thought or planning, the mouth varies the sounds and makes patterns, a spontaneous gibberish poetry.

While Mary’s lulling vocables are revered and celebrated, other medieval texts disapprove of the wordless vocables found in the choruses of carols and folk songs. In Piers Plowman (1370-90) – William Langland’s brainbending poem that interrogates 14th-century society in a series of dream visions – workers who won’t join in with the communal farmwork sit and sing beery songs, ‘helping’ to plough Pier’s half acre with a ‘hey! trolly-lolly!’, a symbol of their foolishness and idiocy. The poem’s central figure, Piers – who is sometimes an idealised portrait of an honest labourer, and sometimes a version of Christ, St Peter or the Good Samaritan – grows angry and threatens them with starvation.

Not every early English writer is quite so dogmatic about peasants singing the joyful gibberish of non-lexical vocables. One of the mystery plays performed in the city of Chester features more trolly-lolling rustics, this time the shepherds watching their flocks who see the Star of Bethlehem in the Christmas story. Each play in a daylong sequence was sponsored by a different craft guild: the shepherds’ play, added to the cycle at the start of the 16th century, was the responsibility of the painters. In this pageant, an actor playing an angel sings ‘Gloria in altissimis Deo, et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis’ (Glory to God in the highest; and on Earth peace to men of goodwill). The shepherds, not acquainted with such fancy language, are perplexed, though the medieval audience would have recognised this bit of scripture as the beginning of a familiar hymn. Did the heavenly song start with glore or glere, the shepherds ask themselves? Or perhaps glorus, glarus, glorius or glo, glas or glye?

They carry on like this as far as voluntatis, turning angelic Latin into something approaching gibberish. Yet though they are scared, they are also strangely heartened and reassured by the heavenly music. They decide to sing a merry song of their own as they set off for Bethlehem to follow the ‘starre-gleme’, the light of the extraordinary star. The stage direction reads: ‘Here singe “troly, loly, loly, loo”,’ and the shepherds’ boy encourages the audience to join in. It’s one of those moments muddling sacred and profane in which medieval drama seems to delight. This play makes fun of the shepherds’ rusticity, but perhaps it also hints that solemn Latin is pretty much gibberish to quite a few of the parishioners in an English church? Maybe it doesn’t matter if the angels’ song is gibberish or Latin, or if the audience sings hymns or trolly-lollies. The Lord works in mysterious ways after all…

Three decades later, Protestant reformers disapproved of Catholic mystery plays, and they also frowned on the happy singing of gibberish in folk songs. Vocables such as ‘trolly-lolly’ or ‘hey nonny-nonny’ symbolised rustic, profane, primitive vulgarity. Myles Coverdale, an English church reformer and translator, published a book of psalms and sacred texts translated and set to music, his Goostly Psalmes and Spirituall Songes (c1535). In his preface, he argued that ploughmen and other labourers and women with their spinning wheels and distaffs would be better off singing pious songs than amusing themselves with ‘hey nony, hey troly loly, and soch lyke fantasies’. The authors of pastoral poetry, a genre increasingly fashionable in the Renaissance, wanted to put clear water between the imagined gibberish of peasants and their own poetic compositions. Michael Drayton, in his eclogues Idea: The Shepherd’s Garland (1593), distinguishes ‘these noninos [nonny-nos] of filthie ribauldry [sordid bawdiness]’ from his more refined verses.

Babies chatter gibberish to us, and we talk back to them as if they had said something utterly astounding

In the following centuries, English gibberish grows relatively dormant. Other related phenomena emerge: there are fashions for nonsense verse, and invented languages – whether angelic, fraudulent, fictional or alien – appear from time to time. Perhaps the age of reason and science finds unintelligible pseudolanguage embarrassing. Gibberish bursts back into view in the early 20th century. Written first by German and Italian futurist and Dadaist poets, and a little later by British and American avant-gardists, sound poetry is written in gibberish spellings representing not words but pure sound. Modernism embraces gibberish as part of its desire to refuse tradition and make all new, but risks ridicule in the process. The American psychiatrist Hervey M Cleckley’s foundational study of psychopathy, The Mask of Sanity (1941), called James Joyce’s book Finnegans Wake (1939) ‘erudite gibberish indistinguishable … from the familiar word-salad produced by hebephrenic patients [ie, those with disordered schizophrenia] on the back wards of any State Hospital’. It was not that Cleckley derided Joyce’s masterpiece per se, but rather that he wanted to point out that you couldn’t tell it apart from insanity. Is it possible to take gibberish seriously as high art?

The Australian-American composer Percy Grainger, perhaps best remembered now for his setting of folk songs, thought that the most important of his works was the one that was sung in gibberish. His ‘Marching Song of Democracy’ (c1901) sought to convey ‘the buoyant on-march of optimistic humanitarian democracy in a musical composition’ by scoring nothing but non-lexical vocables for the choir to sing: ti da-rum pum pa, dim pom pom pom pa ti di. It was first performed at the Worcester Music Festival in Massachusetts in 1917, when optimism about anything humans did must have been in short supply. The ‘Marching Song’ was well-received, though reviewers have always been unsure about what one critic politely calls its ‘eccentricity in scoring’. It was revived for the 2019 Last Night of the Proms: gibberish perhaps the only way to find unity during the post-referendum Brexit wars.

Gibberish always seems to exist in this uncertain state: is it trivial or valuable, is it a symbol of immorality or a kind of pure, natural, musical expression, perhaps even divine? The most paradoxical of gibberish’s qualities is the key part it plays in how we learn to speak not-gibberish. Babies’ babbling (or ‘infant vocalisation’ as it is more formally known) is vital to language acquisition because it prompts carers to stage mock conversations with babies. Babies chatter gibberish to us, and we talk back to them as if they had said something utterly astounding. Also needed for language development is ‘contingent imitation’, those interactions where caregivers copy the babble of babies and infants who burble at them. Recent research from Japan shows that contingent imitation is particularly valuable for increasing the social engagement of young children with autism. If we harness humanity’s natural talent for gibberish, our children will be more fluent speakers of intelligible language, a truth long understood. A 14th-century English translation of a 13th-century Latin encyclopaedia explains how nursemaids help children learn to talk by deforming language gibberishly: ‘the norse whilispith and semi-souneth the wordis, to teche the more esiliche the child that can not speke’ (the nurse lisps and half-says the words the more easily to teach the child that can’t speak).

To create gibberish is both to flee from the familiar features of our mother tongue and yet also to draw on our deepest understandings of what language is and how it works. Gibberish plays a vital role too in giving us our own language as babies and infants. Writing about the work and methods of philosophy in his Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein values the ‘bumps that the understanding has got by running its head up against the limits of language. These bumps make us see the value of the discovery.’ Gibberish is perhaps the bumpiest of human communications, yet through it we discover much about language, its possibilities and its boundaries.