Please note: this essay deals explicitly with suicide and may be distressing to some readers.

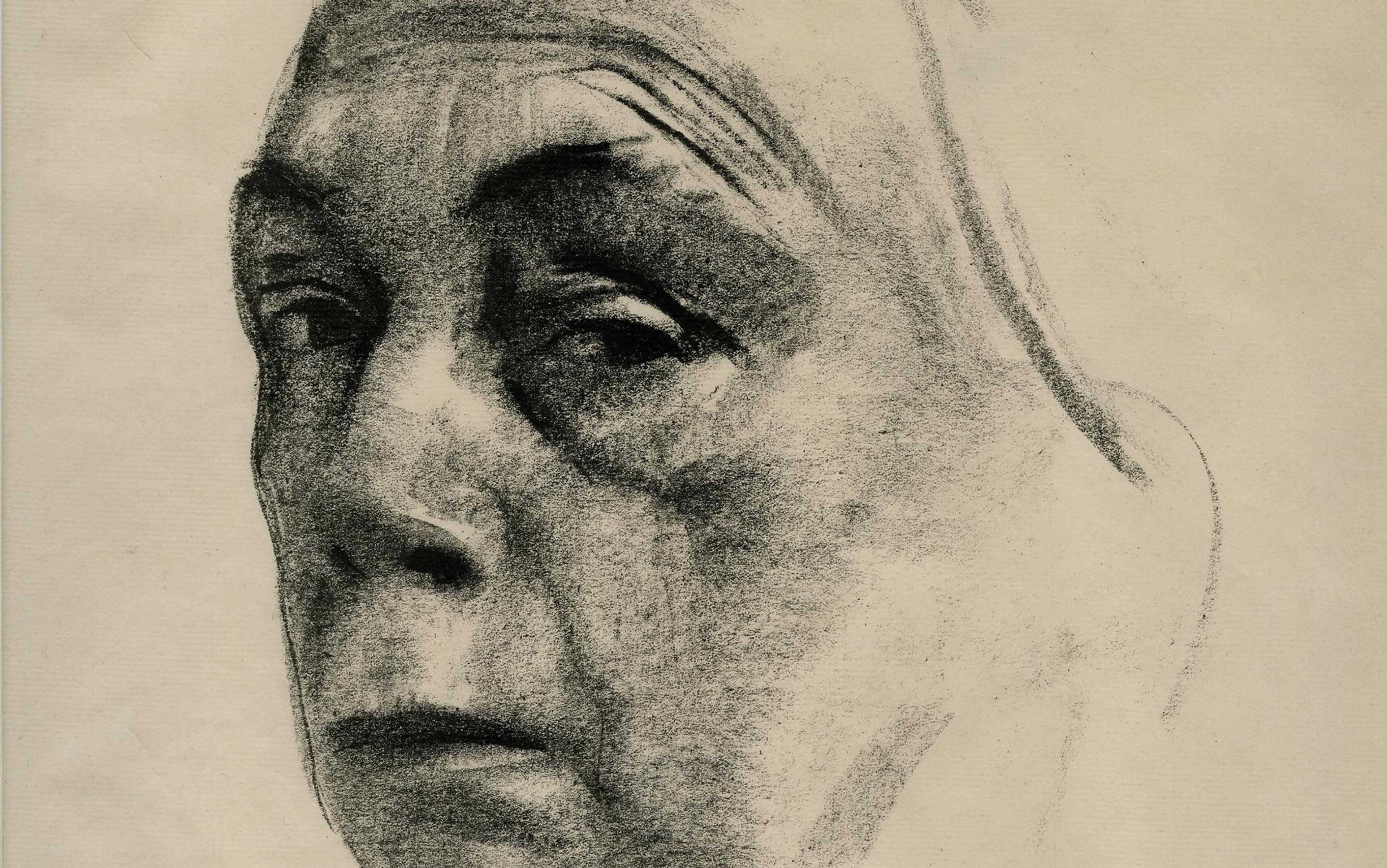

I stood at Anna’s bedside, marvelling over her porcelain complexion, thick blonde hair, and eyelashes so long they’d be the envy of a Maybelline model. The bleached white sheet tucked under her chin covered all but her left hand, which peeked out from underneath.

My 17-year-old daughter would cringe and bat my arms away whenever I’d attempt to smooth her hair, which cascaded down her back like a sunlit waterfall until she had it bobbed to her shoulders at age nine, and chopped into a pixie cut at 15. Tentatively I reached out to feel it, sweeping every strand from her forehead so I could soak in the tiniest details of her face. Anna, the type of child who would argue that the sky wasn’t technically blue, had rarely appeared this calm.

Looking down upon her, I remembered the time she twirled and giggled while jumping to catch fireflies. I remembered how she begged for a puppy and a horse and a younger sibling. For a golden flute. For vanilla ice cream. How she loved birds, and enjoyed trekking through the woods behind our northern Indiana home, notebook clutched in her hand. But I also remembered how her brows seemed permanently furrowed, frozen in a state of unrelenting irritability. I thought about the time, 10 years ago, when Anna stood in the emergency room hallway and screamed that her two-year-old sister was faking a febrile seizure. I recalled the moments three years earlier, when her barrage of complaints tainted our family trip to Disney World, the self-proclaimed happiest place on Earth.

Allowed to stroke her hair again, I also thought about her fiery rages, the dark moods that cloaked her adolescence, and the 12 years I spent searching for answers that would ease both. Because of issues ranging from the difficulties in diagnosing children with mental health disorders to a dearth of clinicians and therapy options in some parts of the country, compounded by adolescents’ reluctance to follow treatment plans, I had been stuck with the question, just like many other parents: will my child ever get better?

A belt buckle cracked against the outside of the bathroom door, punctuated only by Anna’s wailing. ‘I hate you!’ Anna, then six, screeched during one oppressively hot summer day in 2007. ‘I wish you would die! I want to die! I’m going to kill myself!’

Drenched in sweat, I cowered on the other side of the door, huddling with my 18-month-old, who clung to her green security blanket. My phone was perched on top of the toilet seat, and I couldn’t decide whether to call the police, yet again.

The daily rages over anything – or nothing – erupted quickly and lasted for hours. In between, she was constantly irritable. I spent my days feeling like I was carrying TNT, not knowing when a spark would ignite an explosion. The spark could be a smell. The word ‘no’. A neutral glance. Within 20 seconds, my daughter would transform, behaving like a swarm of bees chasing someone into a pond – not letting up until the victim nearly drowned.

The behaviour started in kindergarten, and occurred at home, at school, and on weekends. I dutifully drove her to appointments with a therapist and a psychiatrist, who characterised the behaviour as a symptom of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) combined with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), a behavioural issue some experts contend could stem from permissive parenting or a past riddled with either abuse or neglect. But I wasn’t permissive. Anna had never been abused or neglected. Like many seeking answers, I hit the books and kept a notebook about her extreme rages. When I asked Anna’s first psychiatrist about her extreme tantrums and outbursts, his warm brown eyes couldn’t mask his dismissive body language and cautious remarks that her behaviour was likely just an extreme case of ODD. He offered an antipsychotic mediation, Zyprexa, to her drug cocktail. But the medication didn’t work; the symptoms continued, and Anna’s diagnosis remained ADHD and ODD for years.

Our family had become caught in a cycle of issues formed when an unclear diagnosis leads to improper or delayed treatment. Psychologists and psychiatrists point to several reasons for this widespread issue, from the skill and training of the clinician, to the limitations of the way that diagnoses are made, to multiple disorders that exhibit themselves in the same child.

I went in to tell her the time-out was over. She was trying to choke herself with her belt

‘We also don’t have genetic markers yet for any of these illnesses; we don’t have blood tests, so a lot of the diagnosis is based on observation and interviews,’ said Jill Emanuele, a psychologist in New York and senior director of the mood disorders centre at the Child Mind Institute. ‘The other challenge in diagnosing children is that they change really fast, so the presentations of their illness can change pretty quickly.’ A child brought in to a psychologist at age six with symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity might be diagnosed with ADHD, but the same symptoms might lead to a diagnosis of depression in a 13-year-old.

After Anna’s psychiatrist retired, another child psychiatrist in our area, whose office hours were limited to one day a week, began seeing her. I continued writing in a behaviour diary:

10-23-2010: Anna yelled for a half an hour and didn’t want to go to her room. Finally got her in her room but she began hitting her arm against her bunk bed. She finally quieted down so I went in to tell her the time-out was over. She was trying to choke herself with her belt.

9-22-2011: Anna came home from school and I reminded her to study for her spelling test. She refused, so I told her she would lose computer privileges. I bent down to unplug the laptop and she punched me in the chest. I pretended it didn’t hurt because that would make her angrier, but I called the police and drove myself to the doctor.

She had broken my sternum. After a nine-day stint in a mental-health facility, she received new medications, but I received no new answers. Those were still percolating 600 miles away in Bethesda, Maryland, where the psychiatrist Ellen Leibenluft, chief of the Section on Mood Dysregulation and Neuroscience with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), had been researching the problem of severely irritable children for years, and had a possible diagnostic answer for Anna’s struggles: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, or DMDD.

Leibenluft served on the team that recommended DMDD be added to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-V) in 2013. The DSM is the periodically updated handbook used around the world to help professionals diagnose mental illnesses. Children diagnosed with DMDD must meet several criteria: chronic irritability, severe and frequent temper outbursts – more than three times a week – that are disproportionate to their age and situation, and problems functioning in more than one setting. Symptoms, lasting a year or more, must have appeared before age 10.

Each symptom precisely described Anna.

The relatively rare mood disorder, according to a 2018 article in The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, has a prevalence of only about 1 per cent of the population; even among those at risk for other mood disorders, it appears only 3 per cent of the time. It was added to DSM-V to decrease the number of children diagnosed with bipolar disorder and subsequently prescribed powerful medications for it, including the Zyprexa that Anna once took. Some researchers and psychiatrists were concerned about whether DMDD, occurring alongside other disorders in up to 90 per cent of cases, is a distinct disorder, or simply a collection of symptoms from other mood or behavioural disorders. But the inclusion of DMDD in the DSM-V opened the door for several new studies and clinical trials.

‘These kids have a level of irritability and explosivity that’s a major functional impairment,’ said David Rettew, director of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Vermont Medical Center. ‘They’re not safe. They’re in families where siblings are afraid of these kids; where parents are afraid of setting them off.’

Leibenluft and her team traced the dysfunction to the brain in a study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry in 2016. There, researchers exposed healthy children, children with bipolar disorder and children with DMDD to happy, fearful and angry faces of varying emotional intensity, measuring reaction in the amygdala, the emotion-processing part of the brain, via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans. Notably, all the children were able to label the emotion on each face, but the similarity ended there. The real insight came when comparing children with DMDD with those with bipolar disorder. The children with bipolar disorder showed hyperactivation of the amygdala only in the presence of fearful faces. But the children with DMDD showed hyperactivation – indicating an increase in irritability – across all types of faces, and at every intensity. DMDD was indeed a unique diagnosis, with its own pattern of dysfunction in the brain – and this evidence could be used to double-down, allowing scientists to design new studies for learning still more about this newly recognised psychiatric disease.

Change is difficult, even in adults, so trying to change an adolescent’s mind is even more challenging

I had asked Anna’s psychiatrist about DMDD, and he quickly agreed that the mood disorder was most likely her proper diagnosis. When Anna became disillusioned with the talk-therapy portion of her treatment, and I learned in late 2016 about an NIMH study to evaluate children’s irritability over time using novel techniques, he encouraged her to participate. Initially, Anna was excited to join the study, saying she wanted to ‘advance science’. Though her tantrums had subsided, depression took the place of rage when she was 15, and a stay in a mental health hospital a few months earlier had done little to help. Her grades had slipped. She stopped caring about her appearance, and sunk into online-only friendships. She had felt better during the previous two years, so the depression took us by surprise. Her experience, however, was typical for the disorder – as studies revealed only in recent years. Research has shown that children diagnosed with DMDD often develop severe depression and anxiety as adolescents, even as their tantrums subside.

After several rounds of prescreening phone calls in late 2016, Anna and I were invited to the NIMH campus in February 2017 for the one-day evaluation to determine her eligibility. But by the time we were scheduled to depart for our trip, Anna’s mood had sunk even lower, and she ultimately refused to be in the study. She continued to take her medication, but would lie to her psychiatrist about how well it was working. ‘I hate the world; I hate people,’ she told me. ‘I don’t want to help anybody. We all just die in the end, anyway. We do a bunch of work, become wage slaves, and die … what’s the point?’

When Anna was a young child, I could compel her to take her medication and try new ones, or even visit different clinicians. As a teenager, she would still talk with me about some aspects of her mental health, but any suggestion to return to the mental health centre was met with anger and threats of suicide. The psychiatrist Kenneth Towbin, chief of clinical child and adolescent psychiatry in the Emotion and Development Branch of the NIMH, suggested that it’s common for adolescents to eschew care, whether for mental illness or juvenile diabetes or other chronic medical illnesses. ‘There are a host of reasons that have to do with the developmental period, features of the disorders themselves, family environment, community culture – peer and neighbourhood culture – and societal stigma,’ Towbin wrote to me. And change is difficult, even in adults, Emanuele noted, so trying to change an adolescent’s mind is even more challenging.

Like other parents in my situation, I couldn’t get through to Anna, who didn’t seem to want help at all. A few months after she decided not to participate in the NIMH study, and five days before the first total solar eclipse visible in North America in decades would darken our sky, Anna walked to a local pharmacy after everyone left the house and bought a box of blister-packaged, over-the-counter sleep aids. When she returned home, she filled our bathtub with water, and swallowed every lavender pill in the box.

As partial paralysis crept over her body, she had second thoughts, and managed to dial 911 before stepping into the tub.

After three days in the hospital and five more in the mental health centre, Anna returned home. The psychiatrist who treated her there told me he didn’t know how to help her, because she resisted all treatment suggestions and refused to participate in group activities. Therefore, she was released with the same medications. The same suggestions to continue talk therapy. And she felt exactly the same, too.

During the following year, I tried to remain hopeful, but I was on edge. Statistics show that a serious suicide attempt often leads to another within six months. But six months passed, and then nine. Anna landed a job at McDonald’s for the summer and enjoyed it. Even though she complained about her depression and was unwilling to try the lithium her psychiatrist suggested, she begrudgingly agreed that I could schedule a consultation for electroconvulsive shock therapy, an outpatient procedure proven to ease the symptoms of depression. She earned her driver’s licence and talked about plans for her senior year – tentatively, but she talked about them.

Maybe she’d make it through this, I thought. I stopped worrying so much when we left her home alone.

But exactly a year since her suicide attempt, and a week before the beginning of her senior year, Anna grabbed her purse and headed out the door, casually telling her 12-year-old sister that she was picking up dinner at McDonald’s. I didn’t think anything of it until my husband pointed out that she hadn’t returned home after two hours.

‘Where are you???’ I texted to her at 7:18pm. My phone rang within 30 seconds, displaying a number I didn’t recognise. When I answered, I heard the squawk of a police scanner, followed by a man’s brusque voice.

I envisioned the front of our red Toyota Prius smashed and buckled, the result of a rear-end collision with a car an hour away. I imagined Anna arguing with the police officer about why it wasn’t her fault.

Unlike her mental health diagnoses, these injury descriptions were assertively precise

‘Come to the hospital quick,’ the police officer urged. ‘She jumped off a parking garage. Right now she is still alive, but that’s all we know.’

After ending the phone call, I crumpled into a heap and screamed.

At the hospital, my husband and I were told that someone found Anna, unconscious, in the alley behind the parking garage; no one knew how long she had been there, nor did she have any identification on her. Because police didn’t see much blood, they thought perhaps she had overdosed. A closer look showed some bruising and blood, so police then determined she might have been assaulted. But early X-rays revealed a fracture of her calcaneus, or heel bone, which is a common injury sustained after falling from a tall ladder or greater height. The discovery led police to the roof of the parking garage, where they found her purse, paper note, phone and glasses.

Eventually the trauma doctor, dressed in pristine scrubs, began detailing each of Anna’s injuries and issues, pointing to his corresponding body parts as he talked. Unlike her mental health diagnoses, these injury descriptions were assertively precise.

‘We tried our very best,’ the doctor said finally, shaking his head. ‘But after a certain amount of time, and doing everything … the injuries … we knew she would not survive. There was nothing more I could do. She did not survive. I am so very, very sorry.’

For me, the jagged pain of her suicide had been partially sanded down before it even happened, smoothed by years of visiting different therapists and psychiatrists, reading about diagnoses, feeling misunderstood, experimenting with different medications, feeling hope, having hope dashed. I’m sure DMDD was a correct diagnosis for Anna’s early problems with rage and irritability, but I feel it came too late for us to prepare for the deep depression that would consume her later. Of course, it’s possible that the diagnosis wouldn’t have made a difference – Emanuele suggests that parents should not become overly concerned with names of diagnoses. No person or pill or label could ease what Anna wrote in her final minutes as a life ‘without ever feeling happiness or satisfaction’, according to a lengthy note she wrote on her iPhone and posted on Reddit before she jumped. Diaries she left behind showed that she had been planning her suicide attempt of 15 August 2018 since May.

‘I remember around 12 years of age, I began to have fleeting thoughts of suicide. I never really understood it much back then,’ she wrote in the note, the link sent to me by one of Anna’s online friends. ‘It’s been years since then, and those fleeting thoughts only got worse. Nowadays, I have spent large portions of my time thinking about suicide.’

My hope is that more people enter the field of child psychology and child psychiatry

Anna shared in the note how she wished she could have left her mark on the world, but that life was too painful. She couldn’t claw her way out of the black hole that enveloped her mind and squeezed away every ray of sunshine. Her hope, she wrote, was that the Universe could be erased, so no being would ever have to suffer again.

On the night Anna died, a social worker led us to a room where we saw her for the final time. Although stricken with a deep sadness, my only reaction was to approach her bed gingerly, and then woodenly stroke her hair. I wanted to know: why? Why didn’t she hold out a little longer? Why couldn’t we have made it to the consultation for a different therapy? What more could I have done? But as my thoughts wandered back to her note, I realised her pain was something I could not understand. Despite my own suffering in that moment, I knew that Anna’s hope was not my hope.

My hope is that more in this Universe will take mothers of young children seriously when they worry about their child’s mental health, and not dismiss their concerns. My hope is that more people enter the field of child psychology and child psychiatry so that there are more treatment and provider options. My hope is that more researchers will advance research into mental health disorders and neuroscience. My most ardent hope, however, is that after years of waiting for a diagnosis and treatment, no other mother is forced to contemplate that her daughter’s final, calm expression might have been her most peaceful one ever.

With those hopes in mind, I reached down and stroked Anna’s blonde hair for the last time.