The pharaoh was dead. Now the embalmers and the priests went to work: over the next several weeks, they prepared the body at length. They removed the internal organs, and inserted plant resins and spices into the body. The body was dried out with natron, a natural salt compound; it was washed; covered with oil and spices and more plant resins. Then they wrapped the body in layers of linen sheets and bandages, and these too were covered with resin and oil. They placed the body in a coffin and brought it in a funeral procession to the tomb. For thousands of years, Egyptians practised variations of this basic process, for royalty as well as other elites – all with the care fit for the body of a god. ‘Ægyptian ingenuity was more unsatisfied, contriving their bodies in sweet consistences, to attend the return of their souls,’ wrote the English doctor Thomas Browne in 1658. ‘But all was vanity, feeding the winde, and folly.’ These elaborate efforts to prepare the bodies for eternal life in their tombs would fail.

The mummies couldn’t stay hidden forever. Royal or non-royal, however secret the burial place, hundreds of generations of tomb-robbers hunted them. Those that survived have been left for archaeologists to remove. And today, mummies are all around us. They are so common that we take their display for granted. They have been exhibited in museums in Europe and North America for the past two centuries. During that time, scholars have used ever more powerful tools, from unwrapping and dissection to X-rays and most recently CT scans, to study their insides. They have provided us with information about both life and death in ancient Egypt that was unimaginable just 200 years ago. But mummies have been taken out of Egypt and collected in the West for much longer than this. When we look at the entire history of mummy collecting, we look into a mirror that reflects some dark truths. Mummies tell us not just about ancient Egyptians but also about ourselves.

For most of the history of European collection of mummies, the primary thing Europeans did with them was grind them up. At first, Europeans ate them – mummies were considered a drug. ‘Mummie is become Merchandise, Mizraim cures wounds, and Pharaoh is sold for balsams,’ as Browne wrote. But it all started with a ghastly translation error. The word ‘mummy’ comes from the Arabic and Persian mumia, meaning bitumen, a form of petroleum. (This in turn might have come from the Persian word mum, ‘wax’). Medieval Arab physicians such as Ibn Sīnā (known in Europe as Avicenna) thought that mumia, bitumen, had medicinal value. They inherited this view from classical authors. Some of these medieval physicians suggested that mumia – sometimes meaning bitumen, but more often some combination of resin and spices – was used in embalming ancient Egyptian bodies. When these ideas continued to circulate, in the Middle East and especially in the Latin translations and handbooks of European doctors starting in the 12th century, they were generally misinterpreted. The European writers thought that mumia was a product of the corpses: the embalming resin and spices mixed with juices from the bodies. After a time, many thought that the corpse itself was the medical mumia.

By the 15th and 16th centuries – the height of the European Renaissance – there was a thriving trade in mummy. The production took place on almost an industrial scale: European travellers to Egypt were regularly taken to burial grounds at Saqqara near Cairo, where they witnessed local Arabs digging up mummies to be shipped to Europe. Some tried to take the process into their own hands. The German traveller Johann Helffrich spent two days at Saqqara digging for mummies in vain. In 1586, John Sanderson, an English merchant, bought 600 lbs of mummy and brought it back to London, to sell to the apothecaries. In Europe, mummy found eager consumers. It was used at the English court of Edward IV. Francis I of France was reported to never go anywhere without some mummy combined with rhubarb. By the late 17th century, Russia – which had been a late holdout – came to embrace mummy too.

Mummy was not the only form of dead human that Europeans believed possessed valuable medicinal qualities. Medical books from the 16th and 17th centuries mention drinking blood and ingesting moss growing on skulls, among other remedies. Pierre Pomet, chief druggist of the Sun King Louis XIV of France, expressed scepticism of mummy, but praised ‘Man’s Grease’ (that is, ordinary human fat) as good for gout and nerves. Mummy, however, was the most celebrated and most widely used form of medical cannibalism. And it had many uses. ‘Mummy hath great force in Stanching of Bloud,’ wrote Francis Bacon in 1626. For one authority, it was ‘an excellent remedy against diseases arising from cold and moisture’; for another, it cured any sort of ulcers and stones. Pomet added ‘Epilepsies, Vertigoes, and Palsies’ to the list of conditions for which it was prescribed.

Even in the heyday of mummy medicine, there were protests against its use. For one English visitor to Egypt in the 16th century, Saqqara was an uncomfortable reminder of the drug: ‘These dead bodies are the Mummie which the Phisitians and Apothecaries doe against our willes make us to swallow.’ By the 18th century, complaints were widespread, and doctors were prescribing it less, and fewer apothecaries were stocking it. It was said to be increasingly hard to get authentic mummies, because Egyptian authorities had supposedly prohibited their removal, or because the supply had been exhausted. Instead, European writers speculated that recent travellers who died in the Arabian desert, or executed criminals in Europe, were filled with resins and bitumen and passed off as mummies.

In all the complaints and warnings over mumia, few seemed bothered by the fact that people had been ingesting human beings. The use of mumia didn’t really decline because cannibalism caused people misgivings – it stopped because doctors and druggists doubted that it had any medicinal value. Many experts weren’t sure what mumia was at all, and for good reason. Mummy could be a liquid – like Othello’s handkerchief (‘dyed in mummy, which the skillful/Conserved of maidens’ hearts’) – or it could be a powder, as in Ben Jonson’s comedy Volpone (1606): ‘Sell him for mummia – he’s half dust already.’ A lawsuit over the Duchess of Norfolk’s unpaid pharmacy bills glossed mummy as ‘Mannes fflesshe dryed’; the 15th-century Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi reported how some residents of Cairo were arrested for boiling corpses into oil to sell to the ‘Franks’. Encyclopaedias and reference works of the 18th century – including Samuel Johnson’s celebrated A Dictionary of the English Language – quoted all these definitions and more, adding to the confusion, but references to mummy’s medicinal use were quickly becoming outdated.

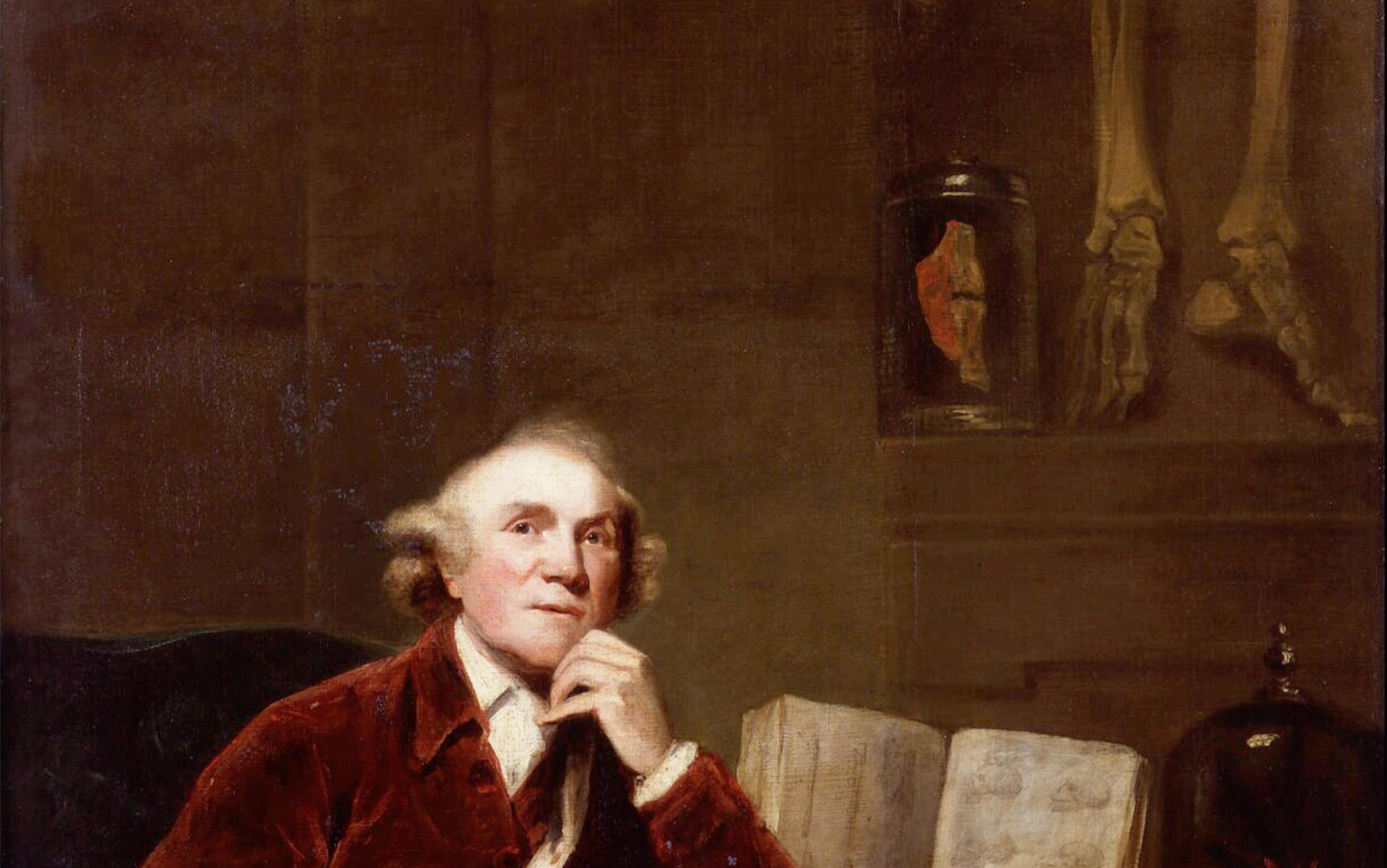

Though no longer fashionable as a medicine in Enlightenment Europe, ground-up mummy now had value as a pigment for artists. The supposed difficulty of acquiring Egyptian mummies didn’t hamper the wide use of ‘mummy brown’. The pigment was popular with European painters for hundreds of years, starting by the end of the 1500s. Within two centuries, it had made its way across the Atlantic. The artist Benjamin West advised his American colleagues, such as John Singleton Copley, to glaze their paintings with it. ‘The finest brown used by Mr West in glazing,’ observed his fellow painter James Forrester, ‘is the flesh of mummy.’ West’s advice was circulated widely over the next several decades. A poem dedicated to West’s contemporary Angelica Kauffman spent some 25 pages celebrating her use of dead Egyptians in her paintings (‘The pulveriz’d Nitocris now/May grace some Queen’s majestic Brow’). In the 1800s, the French Romanticist Eugène Delacroix painted with it; so did English Pre-Raphaelites such as Edward Burne-Jones. Copley’s painting The Death of the Earl of Chatham (1781) and Delacroix’s decoration (1851-54) of the Salon de la Paix in the Hôtel de Ville, Paris are two of the specific works that we can say were painted with mummy in this period.

The Artist and his Family by Benjamin West c. 1772. Courtesy the Yale Centre for British Art.

As with medicinal mummy, people kept debating about mummy brown and how to make it. Which part of the mummy was best? Was it really made of authentic Egyptian mummies? Some suggested that mummy brown was largely bitumen with some animal remains mixed in. Others disagreed. We are told by Forrester that ‘the most fleshy are the best parts’ – he added that ‘the thread of the garments, or any dirt which may prevent its grinding, must be intirely [sic] cleared away.’ One English chemist insisted that the typical procedure is to grind up all of the mummy together, including the bones, to give the pigment greater solidity. In 1926, the colour-maker C Roberson & Co still advertised its own version: ‘A pigment prepared by grinding together the Bitumen and Bones of an Egyptian Mummy.’

Is it the ancient dead that we’re respecting, or our own present-day sensibilities about death?

It is hard to know what to make of these duelling 19th- and early 20th-century claims. Should we take them seriously and, if so, which ones or how many? Some of them are quite glib – one artists’ handbook frowned on mummy brown by insisting that there is ‘nothing to be gained by smearing our canvas with a part perhaps of the wife of Potiphar’. Some are quite graphic, with lurid anecdotes of London colour-makers grinding up mummies in their mills. Here we read that genuine Egyptian mummy can be obtained at colour shops; there, that it is increasingly scarce, because of a familiar reason: Egyptian antiquities laws. Adeline’s Art Dictionary (1891) warns that what ‘the druggists of the Levant palm off upon Western Europe is not genuine … but is obtained from the bodies embalmed by both Jews and Christians in the Levant.’

Now, stop for a moment.

Step back and think about what you’ve just read. Maybe you were captivated, maybe repulsed, maybe some of both? Take a moment to think about why that might be. How different are we from people who used to eat and paint with mummy? Extraction of mummies is still tomb-robbing, whether for medicine or for science. When an ancient sarcophagus discovered in Alexandria, Egypt was opened in 2018 and a red liquid found inside, a petition circulated on Change.org with tens of thousands of signatures to ‘let people drink’ what in fact was probably leaked sewage. The widespread trade in mummies and other human body parts in online platforms such as Facebook and Etsy suggests that the gulf between past mummy users and ourselves is smaller than we might at first imagine. It’s important to remember, though, that mummy-eating and painting were once socially acceptable activities in Europe and the US. Today, wishes to drink mummy juice are highly eccentric. Maybe there is a fundamental difference between past and present after all.

One recent change is that archaeologists and museum professionals, in ethical codes, exhibitions and publications, now emphasise the concept of ‘respect’ for the ancient dead and the need to recognise them as human. Yet Egyptologists still carry out much the same research on mummies as before. Museums still display mummies, sometimes unwrapped, and usually alongside pictures of their insides. In exhibitions, the most visible changes include prohibiting photography of unwrapped human remains and putting up signs warning that human remains will be on display. With such gestures, is it the ancient dead that we’re respecting, or our own present-day sensibilities about death? If we recoil from an unwrapped mummy – or from reading about what modern humans have done to them – it might not be out of respect for them so much as disgust at the thought that we might let our own bodies come into contact with ancient human flesh. The remarkable thing, then, is that so many human beings 500 or even 200 years ago didn’t share this disgust. What happened?

Since Philippe Ariès in the 1970s, the history of death has been its own field of scholarly study. And since Ariès, scholars have shown that attitudes toward death have transformed dramatically over the past few centuries. One of many critical changes is how we interact with dead bodies themselves. Before the previous century, death could strike at any time – childbirth for newborns and young women, epidemics for anyone. Death was familiar, intimate even. Bodies might pile up in an epidemic, but they were also present in the home. Families took care of loved ones in their last moments, and of their bodies after death.

Over the past 200 years, in industrialised countries, all of this has changed. With improved public health has come a drastic fall in infant mortality; with vaccines and other medical advances, the curbing of many epidemics – with occasional deadly exceptions. Death is more and more confined to old age. It takes place in the hospital. Between the nursing home, the hospital and the funeral home, the entire process of caring for family members before and after death has been moved out of the home, and out of the sight of most people.

These changes in when and where people die have brought a major shift in attitudes towards death, and towards the dead body. Until very recently (two centuries ago at most), death was seen as inescapable, a natural part of life. People were used to dead bodies. There was a ‘promiscuity’ between the living and the dead, as Ariès has put it. Now, death is invisible. We are much less used to dead bodies, much more apt to recoil from death – and from the dead. Between the distance we feel from death and the rise of germ theory, we might shudder at the thought of painting with or swallowing human flesh.

Let’s consider an example, a custom of how we live with the dead. For hundreds of years, middle- and upper-class families throughout Europe (and eventually in the US) had postmortem portraits made of their loved ones – especially, but not only, their children. These portraits showed the deceased lying peacefully as if in sleep instead of death, first as paintings, then as photographs. Today, the practice strikes many as a Victorian oddity. But in fact a version of it continues to be practised – just not among the upper classes. Postmortem portraits, taken by professional artists advertising for this particular service, were once framed and put on display in homes or kept in family photo albums; now they are more hidden. The anthropologist Jay Ruby, among others, has shown this custom’s durability, in the US at least. It is now practised primarily by the lower-middle class, and the ignorance of many as to its existence might have to do with a restricted knowledge of other classes. Postmortem photographs today also focus more on the funeral party as a whole, instead of a close-up of the deceased. But what is key is that this practice is no longer socially acceptable for many who see this intimacy – what Ariès called this ‘promiscuity’ – with the deceased as quite alien.

If it was acceptable to display photos of our dead at home, it was acceptable to display the ancient dead in a museum

Practical changes in medicine and hygiene have had dramatic consequences for how we think and feel about death. They have made both modern and ancient dead more distant and foreign alike. Just as postmortem portraits are no longer a publicly acknowledged practice, just as drinking mummy juice is not socially acceptable, so there has been a move towards restricting public displays of mummies. When mummies first went on show in museums two centuries ago, people in Western countries were likely to have more direct experience with dead bodies. If it was acceptable to display photos of dead loved ones in the home, it was acceptable to display the ancient dead in a museum.

Mummy display has gone on for so long that we now take it for granted. But there have been changes in how both professionals and public see them, however subtle. Consider the transition from spectacles of public mummy unwrappings in the early to mid-19th century, to a more clinical procedure for specialists, to increased reliance on imaging the insides. The technologies used to study them might represent less and less destructive ways of viewing mummies and their insides – but they also reflect greater distance from direct contact with the dead body itself. In recent years, museums have occasionally tried to change how they display mummies. The Manchester Museum briefly covered some unwrapped mummies in modern cotton shrouds in 2008, saying that it wanted to raise awareness about the ethical issues of displaying dead bodies; the coverings were removed within a few weeks, however, as visitors complained about the change.

At least some displays of dead bodies in museums continue to be popular. Mummy exhibitions are huge draws. Starting in the mid-1990s, a series of exhibitions under the title Body Worlds has displayed corpses and body parts preserved by a process called plastination (replacing body fat and water with plastic, so that the bodies don’t decay) and arranged in various lifelike poses. Tens of millions of people have visited these exhibitions and the various knockoffs they have inspired. But mummies aren’t like ordinary dead bodies; they are the long-ago deceased of another civilisation, ones we often see as artifacts more than as people. Body Worlds, meanwhile, does everything it can to make the bodies on display look unlike corpses. Far from putting dead bodies on show, it hides them – it makes death invisible.

If changes in how we treat mummies really reflect practical changes in how we experience dead bodies – changing what we then project on to an ethical plane – what does this mean for how we might treat mummies in the future? Thinking about these issues seems especially appropriate now, when routines of daily life and the rituals of death have, for so many of us, been upended in a short time. We know that attitudes toward the dead, both ancient and modern, have changed drastically at multiple points in history. They might be about to change again.