There was a time – I was still young, in my mid-20s – when I thought I was going to be a perennial traveller, a woman without a country or permanent address, a vagabond. Not that I was ever the backpacker type. I liked lace blouses and high heels too much. In my fantasy image of myself, I floated from place to place in long flowing gowns. In real life, I travelled heavy, lugging way too many suitcases wherever I went.

I chose to go to graduate school in anthropology, hoping this adventurous discipline would open wide the roads of the world to me. Upon completing my dissertation, I learned I was expected not to satisfy my wanderlust, but to get a job teaching anthropology. I dutifully went for a job interview at one of the small Ivy League colleges. From the moment I set foot on the campus, I knew I didn’t want the job, but I felt I ought to want it. The job was a two-year replacement position for a faculty member who was going on leave and possibly would move on. ‘Probably won’t be coming back,’ they whispered. ‘So it will turn into a full-time job.’ That was the lure. It turned out that the person came back.

The interview went terribly. I could see the professors laughing into their shirtsleeves. I fumbled over the words of my overly long lecture and stuttered trying to answer the clever questions the professors posed. The most famous member of that department behaved the most viciously. Soon after, he committed suicide, which of course had nothing to do with me, but in my mind it was a sign from the gods that I’d been lucky not to end up there. I’ll always remember the room with the ominously low ceiling at the quaint New England inn where I stayed and cried myself to sleep.

I wasn’t ready to settle down. And yet I hoped one day to have a house of my own. After my family emigrated from Cuba, I grew up in crowded, noisy apartments in New York. The last home I lived in with my parents and younger brother had a surrealist entryway that could have been painted by Magritte. As soon as you came in the door, you faced a tall flight of stairs that seemed to go nowhere. If you ventured the climb, you reached the living room, which had a picture window looking out at the ruins of the World’s Fair. I spent my teenage years at the bottom of those stairs, reading books I loved – novels and works of philosophy. This desire for solitude and silence disturbed my gregarious father. He accused me of turning his home into a funeral parlour. The house of my dreams, I decided, would have many rooms, a garden brimming with daisies, and no one to scold me for being quiet.

Unemployed and unmoored, I flew to Mexico in 1983 to accompany my new husband, David, who was beginning his fieldwork in a small town in the craggy foothills of San Luis Potosí. Like me, he had started out in college planning to study literature but followed me into anthropology. ‘That way we can travel together,’ he said. It was a nice thought and we did travel together for many years. Those were happy years, but I worried about losing the courage to go places by myself. I needn’t have worried. As we grew older, he preferred to stay put and I became restless. I began to travel alone, as I had dreamed when I was young.

David and I had contemplated settling in Mexico. We stayed for almost three years. I collected things, pretty things, for the house I did not yet have. I bought starched white tablecloths, embroideries, hand-painted plates, ceramic urns, blue-rimmed goblets, a trunk made of inlaid wood, ink drawings on amate bark, and a chest of drawers with carvings of birds and flowers. Most of these things graced the borrowed rooms where we stayed. It gave me pleasure to be surrounded by the beauty created by the hands of others. But a few things felt too precious for my temporary life in Mexico. I saved them for the house of my dreams.

Eventually, I did get a job teaching anthropology, and the house materialised, a Victorian house in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with many rooms, daisies in the garden, and all the quiet I could ever want. I filled the house with the things from Mexico. Only the chest of drawers was too large to carry across the border in our Volkswagen. It stayed with friends in the town, but I still entertain thoughts of getting it back. And I’ll admit that some of those precious things from Mexico remain wrapped in tissue paper even now, hidden away in my house.

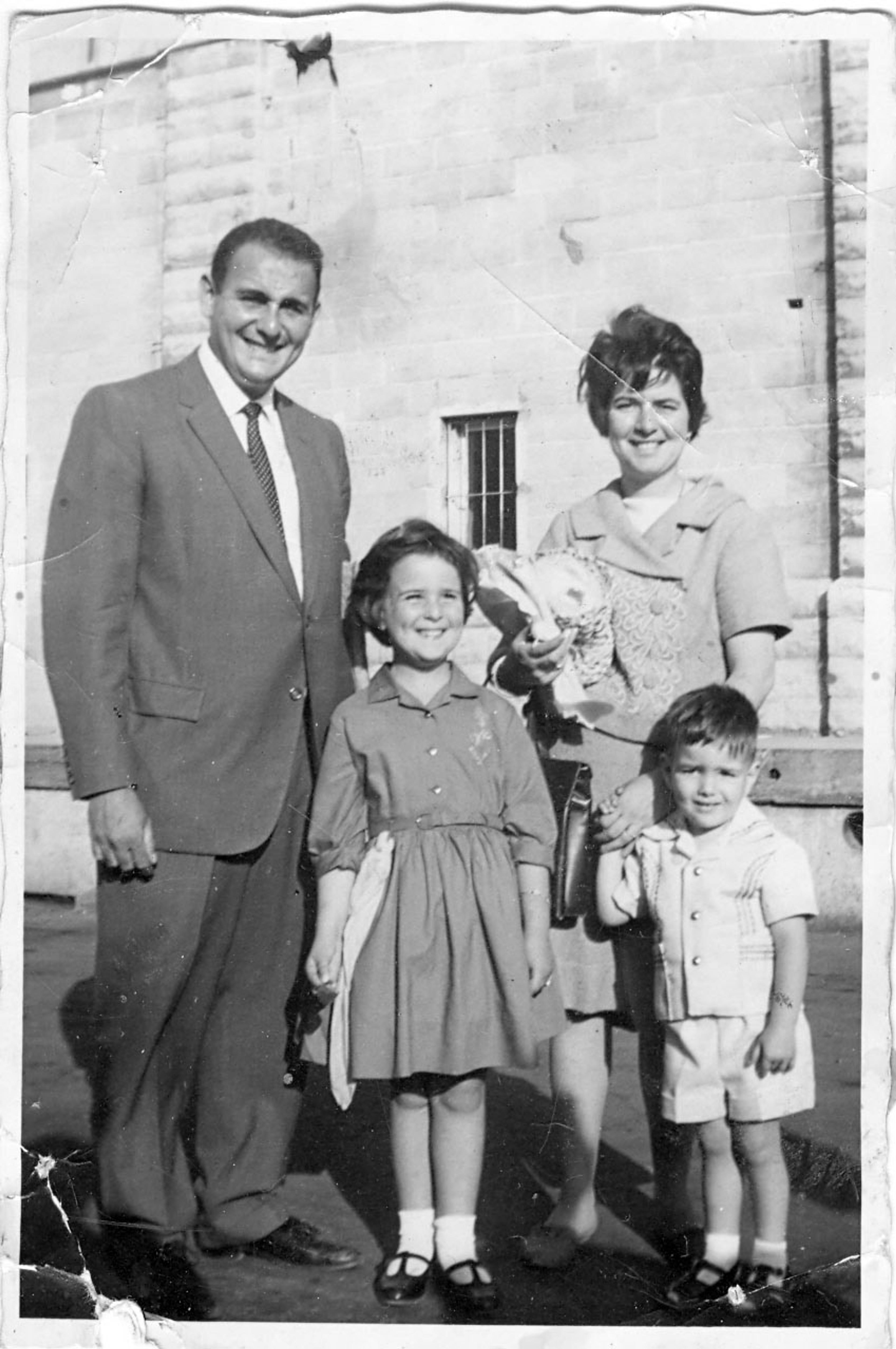

In the past 30 years, I have acquired many more things in the course of many more travels. From Cuba, my native land, where I have returned incessantly since the 1990s, I’ve carried art, sculpture, maracas, batá drums, and even sand from Varadero Beach, where my parents honeymooned. To this, add my vast collection of books in English and Spanish. And add the numerous pairs of high heels required to stroke my vanity. This frivolity is in balance with a desire to be the keeper of my intimate historical past. I am the person in the family who keeps the old photographs and expired passports, the dress my grandmother wore to her 50th wedding anniversary, the nightgowns my mother wore on her honeymoon. At once warehouse and museum, my house is sinking, like a boat, from so much weight.

I have surprised myself by ending up becoming more of a rooted creature than I ever imagined I’d be. I have held on to the same job, the same house, the same address, the same husband (I, who never expected to marry). I gave my son, my only child, who is now the age I was when I thought I was never going to settle down, the gift of an immense stability – firm and steady ground on which to stand.

But when I travel and a stranger asks if I’m from Michigan, I immediately reply: ‘I live there, but I’m not from there.’ I feel compelled to tell everyone about my immigrant past: ‘I was born in Cuba, my ancestors were Jews who spoke Yiddish and Judeo-Espanyol, and I grew up in New York. I live in Michigan because it’s where I work.’

I suppose I fear that people might get a mistaken impression of me if they think I am from Michigan. It’s a desire to tell the truth of who I am, to assert I am a person of many diasporas, I come from somewhere else, I don’t have a firm allegiance to any single place. I am passing through, grateful for a place to rest my wings.

That I should feel adrift after living in Ann Arbor for so many years might seem absurd, but my sense of connection to place is fluid and complex. The meaning of home, I have come to realise, is full of contradictions, and impossible to encompass in a single definition.

Home is a concrete location on a map.

Home is a set of memories that can’t be confined to any map.

Home is the street where you took your first steps.

Home is genealogy, who begat whom, and how you came to be.

Home is the historical record of those who came before you.

Home is the land your ancestors fought for and lost.

Home is the land your ancestors conquered by force.

Home is your kin, those whom you hold dear.

Home is the nest you create with the stranger who becomes your life partner.

Home is the cornfield, the olive trees, the herd of sheep from which you were fed.

Home is the hearth, the home fire, the kitchen that gathers family and friends.

Home is a refrigerator stocked with your favourite flavour of ice cream.

Home is the way your grandmother said your name like a blessing.

And a home is where you put your grandmother when she is sick and useless.

Home is the lullaby your mother sang you to sleep.

Home is the lullaby you wish your mother had sung you to sleep.

Home is a shared language where even your slightest gestures are understood.

Home is where you can lounge in pyjamas all day if you feel like it.

Home is shelter: the house, the apartment, the flat, the shack, the tent, where you can find rest and refuge from the natural elements, from heat, rain, cold, snow, tempests.

Home is your beloved, to whom you bring flowers, gifts, and chocolates.

Home is where you were bored and dreamed of new horizons.

Home is your home page on your website, or your home screen on your cell phone.

Home is a filthy stove, an unmopped floor, dusty bookcases, cobwebs in the corners, accusing you of untidiness and laziness.

Home is that place you vacate in order to go on vacation and forget about your untidiness and laziness.

Home is that place where treasures are stored and thieves lie in wait to steal what they can.

Home is a piece of real estate, to buy and sell.

Home is a mortgage you spend your life working to pay off and resent like hell.

Home is that place between four walls where you were mistreated, abused, raped, hated for no reason, by those who were supposed to protect you and care for you.

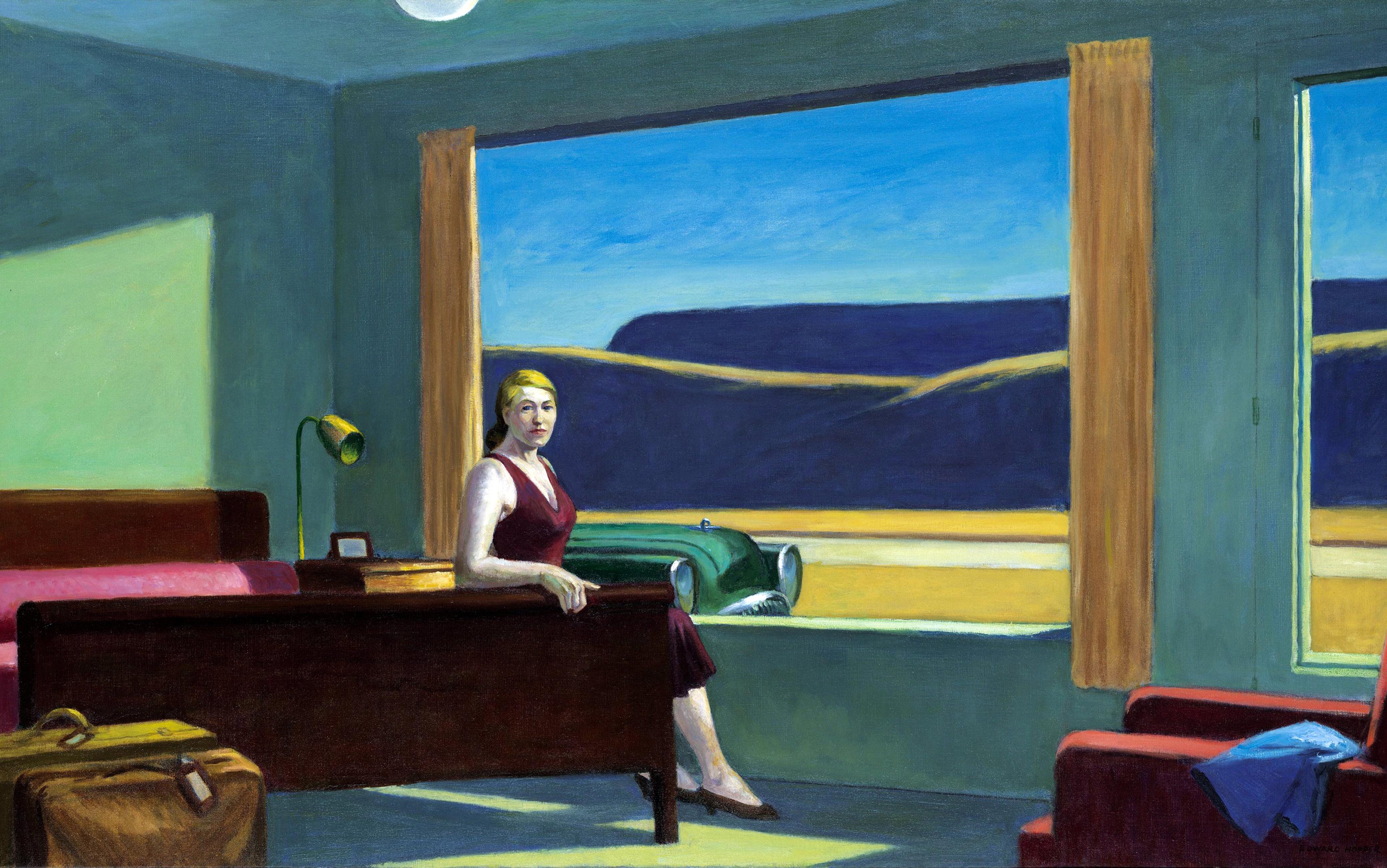

Home is that doll’s house from which a wife wants to escape but lacks the means or courage to do so.

Home is that place where you can be a woman alone and no one feels sorry for you.

Home is that place where you were tortured by a government that fears its citizens.

Home is that place where you went to bed hungry.

Home is that place where you weren’t allowed to pray to your gods openly.

Home is that place where you aren’t afraid to wear a hijab or a kippah in the street.

Home is that place of endless war and strife where you never felt safe.

Home is that place from which you were expelled, told to leave or lose your life.

Home is that place where your ancestors found their final resting place.

Home is that place where your ancestors were brutally dehumanised and left to die without a grave.

Home is that place which took you in like an orphan when you had no place to go.

Home is that place to which you want to keep returning.

Home is that place to which you never again want to return.

Home is that place which is unspeakable in the way that Isadora Duncan once remarked that if she could say what it means she wouldn’t have to dance it.

In an age of massive displacement and global travel, does the concept of home even make sense anymore? At the present time, there might be as many as 200 million people living outside the country of their birth. No one is more disruptive and destructive of the concept of home than the immigrant. But the immigrant also demonstrates an uncanny ability to recreate, nostalgically and therefore imperfectly, the vestiges of an abandoned culture in a different place, while adapting to, even mastering, a new language and society.

Still, no matter how settled, a queasy unsettledness, an existential ambivalence, haunts the immigrant. Let me use my father as an example. On July 4th each year, he proudly displays his American flag on the front porch of the house he and my mother bought long after my brother and I had moved away. But after 50 years in the US, he can’t be sure it’s his final destination. My father keeps 500 $1 bills stashed away in case he and my mother ever have to leave the US in a hurry, just as they had to leave Cuba. ‘Why all $1 bills?’ I ask. He replies, half-joking but also half-serious: ‘Don’t you know? To bribe the guards at the border, so we can get across.’

Ours is a crazily criss-crossing world and there is great irony in the fact that the modern-day traveller typically seeks out exactly those locations that many immigrants desperately sought to leave. I saw this collision of forces at work 20 years ago in Cuba at a time of economic and moral collapse. The ports were thrown open by the government and all who wished could leave by sea. Disaffected rafters risked the journey on any vessel that could float. Meanwhile, 1994 was the year of the first art biennial in Havana to be open to the capitalist world since the Cuban Revolution of 1959. American curators and dealers rushed between exhibits, marvelling at the art they’d missed for decades, then relaxed after the hubbub, drinking mojitos on the veranda of the Hotel Nacional. As they swooned, rafters died in the depths of the ocean, more than we will ever know.

I knew people who worked the land and tended cows and sheep, and never found the time to travel just a couple of hours for a glimpse of the ocean

To be able to travel, especially with ‘the comforts of home’, is a privilege. Those who move about the world without being uprooted from their homes too easily forget this basic fact. Anthropologists are strange travellers in that we go to the same places over and over, unlike tourists who have a checklist and are always going someplace new. I have spent long periods of time with people who haven’t ever travelled, people who have not ventured beyond the towns and cities where they were born and raised. In Santa María del Monte, a village at the foot of the Cantabrian Mountains in northern Spain, I knew people in the late 1970s and early ’80s who worked the land and tended cows and sheep, and never found the time or had the inclination to travel just a couple of hours to get a glimpse of the ocean.

Later, in Mexico in the mid-1980s, I met men who crossed el charco, ‘the puddle’ of the Rio Grande, as a rite of passage, without documents, and worked in agriculture or in restaurant kitchens in the US, but didn’t dare look around too much or go too far, for fear of being caught and deported. Eventually, missing their families, feeling a loneliness that no one should feel, they went back home on their own.

Most recently, in Cuba, I have become close to the woman who was my nanny when I was a child. Now in her late 80s, she has been only to Melena del Sur, her hometown in the countryside, and Havana, the city that embraced her when she went there to accept the only job available to her in the 1950s as a poor black woman – domestic work. She has never flown in an airplane. She has never had to explain her identity to anyone. But any news she receives from her son in Miami, who hasn’t returned in 10 years – whether directly via a phone call or indirectly via an email message sent to a neighbour and relayed to her – she will report in the most vivid detail, as if she had experienced it herself. What she doesn’t know for sure, she will imagine and embellish, for that is the gift of those who don’t leave home – they can weave remarkable stories from the barest of threads.

Pondering the relationship between feeling at home and being homesick has long been an anthropological obsession. The discipline took off from the idea that an anthropologist had to leave home in order to study otherness in a distant place. Knowledge was built through reflecting on the meaning of insider and outsider, familiar and exotic, native and stranger. But in the quest to get from place to place, everything in between, the vast infrastructure of modern life, escaped our notice. We missed the transient places that the French anthropologist Marc Augé has called ‘non-places’ – airports, shopping malls, hotels, highways, bus terminals, and subways.

These ‘non-places’ have radically changed the concept of home, not only for most of us in the first world but for a growing number of those in the developing world. Perhaps nothing has left so strong a mark on our identities as the periods spent in the sky and in the airports that gather together assorted strangers before sorting them on to different planes. An airport ‘hub’ is a stopping point between places. The ‘hub’ is an apt metaphor for how many of us among the privileged are living out the meaning of home in everyday practice. Those who are frequent flyers and spend much of the year moving between places might find that the place we call home has come to seem like the route to elsewhere. Home is where you do your laundry, run to the dentist to get your teeth cleaned, and frantically rest your weary bones before embarking on the next odyssey. In turn, airport hubs are trying to become our homes, offering outlets to recharge our numerous devices so we can continue to communicate from afar, as well as shopping, restaurants, prayer rooms, and massage.

As ‘non-places’ expand from centres to peripheries all around the world, there is renewed pressure to work hard to prevent the home from becoming a long-term hotel room. Sentimental notions of the sanctity of the home are enlisted as a means of challenging the threat of ‘non-places.’ A preponderance of guides, including websites such as Apartment Therapy and Houzz, exist for the sole purpose of assisting us in making our homes uniquely charming and irreplaceable. Home Depot and Pier One have become the iconic commercial outlets offering practical supplies and decorative touches for these homemaking projects that alternately encourage us to be richly rococo or humbly Zen.

We can give up home altogether and be homeless by choice – not as a result of poverty or broken family ties, but to let go of the weight of things

But there is another choice we can make, and that is to give up home altogether and be homeless by choice – not as a result of poverty or broken family ties, but to let go of the weight of the things that prevent us from fully engaging with the world and becoming true cosmopolitans, people at home everywhere.

I had the pleasure of meeting such a cosmopolitan recently in Lafayette, Louisiana, where I’d gone to speak about the theme of travelling heavy. She politely came to talk to me after my first presentation and told me she was a modern nomad. She had given up nearly all her possessions and moved around in a car that doubled as her bedroom and living room. I must have looked at her quizzically, because she recommended a book on the subject that she said would make it all clear. I didn’t get to jot down the title and regretted forgetting it.

Fortunately, the next day, I gave a second talk, and this woman kindly came to hear me again. She brought along the book. It was Tales of a Female Nomad (2001) by Rita Golden Gelman, a writer of children’s books who studied anthropology as her marriage was ending. After her divorce, she decided to live the anthropological dream of satisfying her wanderlust, ‘living at large in the world’. In order to be able to travel constantly, and for her money to stretch, she made a choice to spend much of her time in the developing world – in those places where ‘non-places’ haven’t made a big dent yet. Embracing the quintessential ‘non-place’ of the road, she made a home of it.

I was touched by the gift of this book and held on to it closely.

‘Pass it on when you’re done,’ the woman said. ‘Give it to someone else.’

I nodded in agreement, knowing how bad I am at letting things go. I descend from nomads, people who suffered from expulsions and uprootings, people who could pack at a moment’s notice and start their lives again from scratch. But I am a keeper of things.

I’ll try to give the book away, I promise. Anybody want my copy? You’ll have to come to my sinking house in Michigan to get it.