To read the news in the spring of 2021 was to encounter every day a deluge of columns, editorials and think-pieces – so many think-pieces – on the diverse psychological traumas unique to our liminal moment, our transition out of quarantine, our return to something pundits insist on calling ‘normal’. We read, for instance, about the stresses of returning to the workplace; of leaving pets and family from whom we’ve grown inseparable; of resuming the horrors of dating; of reckoning with the Covid ‘19’ (that is, the pounds we’ve gained); and with the acceleration of addiction (around 40 per cent of drinkers said that their alcohol consumption had increased since the pandemic began). A recent video essay in The New York Times called ‘Are You Dreading a Return to “Normal”? You’re Not Alone’ chronicles a reluctance to return that is, counterintuitively, widespread.

Another terror goes undiscussed in such analyses, perhaps because it undermines our shared romance as self-possessing realists capable of understanding our desires and modifying our behaviours. What I have in mind here is that that some of us seem to pre-emptively miss COVID-19, to fear the moment when it will recede into our collective rear view. We fear a time after COVID-19 not because its passage will require the various reckonings and returns enumerated above. We fear it because we’ve come to enjoy its privations. On social media and in person, we increasingly appear, many of us, to perceive the recession – not exactly of the virus itself but certainly of the relational and cultural formations it engendered – as a psychic loss. It bears stating explicitly that this anxiety is both different from and, in a sense, foundational to the other stresses of re-entry listed above. In those accounts, we’re depicted as fundamentally excited about our return to ‘normal’ and worried merely about the hiccups that will inevitably attend the resumption of regular programming.

Yet for many of us – and, here, I mean a certain kind of reflexively secular, (over)educated liberal – the coming emancipation feels less than happy. Ever since the massive rollout of the vaccine programme in many parts of the developed world, another, incompletely repressed part of us has begun surfacing with greater vehemence. This part seems angry, resentful and, most to the point, betrayed at the premise of return. This part of us seems anxious not only about the conditions attendant upon re-entry but about the very removal of the conditions of emergency and exception we’ve necessarily adopted. As with many cultural barometers today, this one is most legible online, in fora where user comments are hosted. The user sections in online newspapers favoured by moderates, liberals and Leftists alike, as well as in less moderated venues such as Reddit, have begun to feature a particular kind of voice lashing back at any editorial content suggesting that the end of COVID-19 is near. How can we really be sure, they ask? How can we really trust guidance from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) when they tell us to leave our masks at home – especially when they keep changing their minds and they’ve been wrong before? Of those sounding optimistic notes, users demand to know their epidemiological credentials. Is it really responsible, they ask, for anyone but a medical expert to call for return?

The opinion pages and comment sections of The New York Times provide as representative a sample of this affect as any outlet. In late February, the conservative commentator Ross Douthat wrote a column for the paper called ‘The Covid Emergency Must End’. While acknowledging the myriad complications that might prevent the return to normality in the spring and summer, he nonetheless opined that, unlike in the darkest days under Donald Trump:

today the situation is radically different. And Joe Biden would be doing our struggling, freezing country a great service if he suggested, with evidence, that with continued effort and reasonably good fortune, the era of emergency might be over by the Fourth of July.

Douthat’s own evidence came from recent CDC data.

Predictably, most NYT commentators found a good deal to hate in this position. One of the most upvoted and NYT recommended posts came from a user called ‘B1indSqu1rrel’, who wrote, with a punitive assurance characteristic of many others:

Tell me are you in the habit of closing your eyes and relaxing because you are almost home from a long difficult drive, or do you wait until you park your car? Do you often lie down of the floor of your home because it’s almost bedtime, or do you wait and actually get in bed?

In another upvoted and recommended comment, ‘DP’ writes:

If you really would like to help, how about telling people to mask up, wash their hands, and stay the heck away from people as much as possible until this thing is ACTUALLY over, and not trying to get back to normal as soon as things look like they are starting to change? The beginning of a recovery is not a recovery.

Many others simply stressed that Douthat’s lack of epidemiological expertise prevented him from editorialising on this subject. ‘I will follow Mr Douthat’s advice when he shows me his Medical Certification as an expert in infectious disease,’ writes ‘j p smith’.

Writing for The Daily Telegraph in July, Sherelle Jacobs observed keenly that people ‘have become [so] attached to the gilded trappings of lockdown’ that they have shifted the goalposts of what would constitute a safe reopening of Britain. For people in this group, the UK’s prime minister Boris Johnson shouldn’t accept the drastic mitigations of risk offered by widespread vaccination but should instead settle for nothing less than a ‘Zero Covid utopia’.

I am not an epidemiologist, nor am I interested in virology in the biological sense. What I am interested in, and what my training as a literary critic leaves me well prepared to see, is what I call, if somewhat grandiosely, the surplus phobic energy of the response. Some people seem to want or even need something much more existential – spiritual? libidinal? – than the pure scientific accuracy to which they pledge their allegiance. This excess is evident in their aggression toward the very genre of the editorial itself, and their insistence that our moment of emergency can reasonably brook no opinion but the most pessimistic.

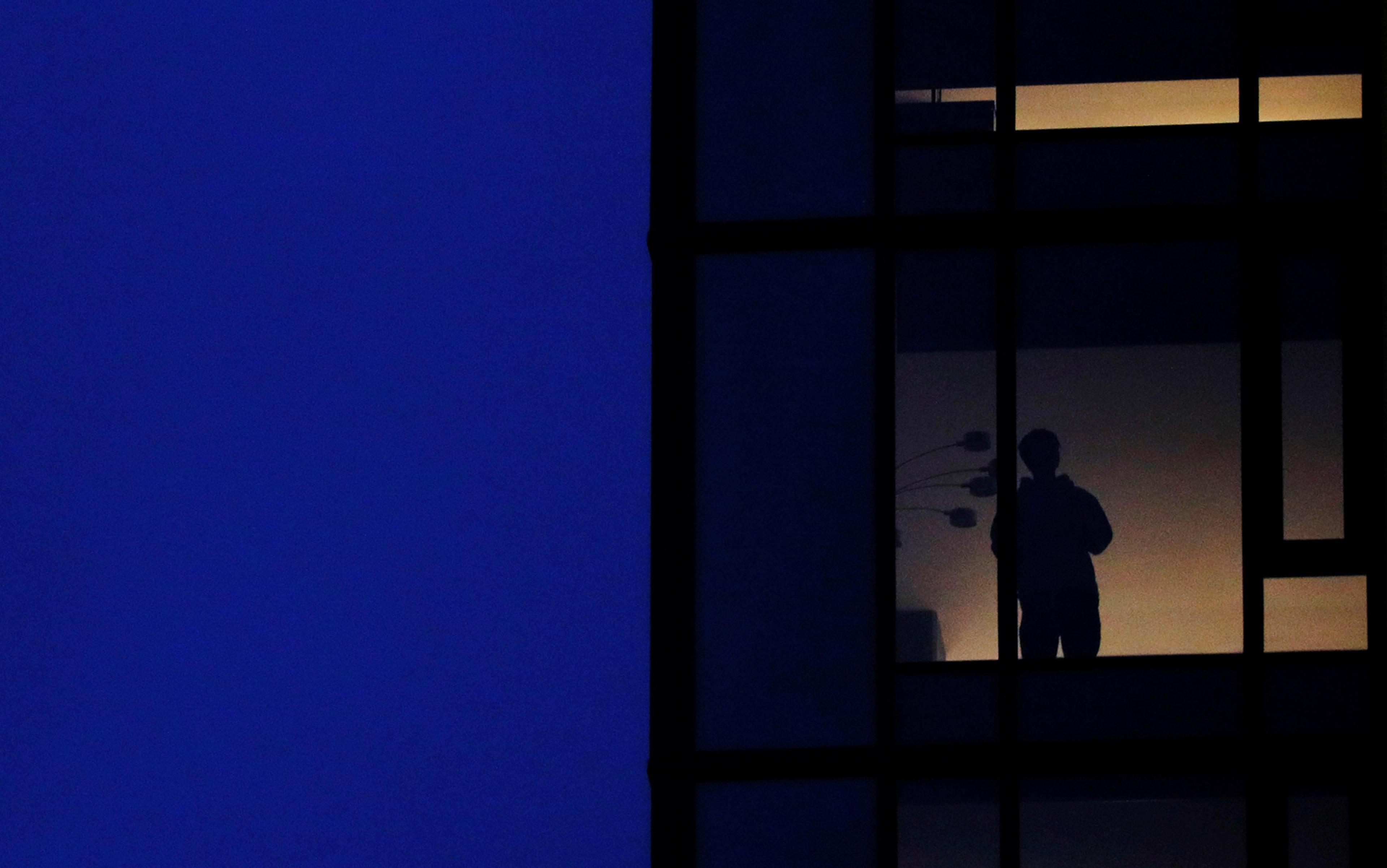

These responses expose part of our collective cultural unconscious that has identified not, perhaps, with the virus itself, but certainly with the conditions of lockdown: with emergency culture, maybe even apocalypse culture, with conditions of prolonged terror and the kind of defensive retreat that terror inspires. (The psychology I’m highlighting here might find its analogue in broader cultural fetishes for zombie narratives, which likewise discover pleasure in dystopian rituals of quarantine and isolation.)

This strange pleasure is different from the so-called ‘pleasures of lockdown’ – reconnecting with family, eschewing long commutes – that were so comprehensively covered in articles such as ‘Loving the Lockdown’ in The New York Times in May 2020. For a long time, this need for protection and security replaced the role fulfilled before the pandemic by in-person sociality itself. But doesn’t it seem naive to imagine that this new culture would just be chucked, wholesale, for an acceptance of what was before? The grim affect that’s emerged online in the past few months seems to suggest as much.

To explain the psychology here, it’s tempting to invoke Stockholm syndrome, where a kidnap victim identifies with the captor; think Patty Hearst. Like some hostages, we’ve been tricked into forgetting the contours of the good, pre-viral life. But I think that the nimbler paradigm for our vexing, residual attachment to a thing we once viewed with justifiable hostility – our condition of privation – comes from Sigmund Freud’s conception of melancholy.

Freud contrasted melancholy with mourning. In the latter mode of processing grief, which he initially thought healthier than melancholy, the mourner slowly accepts the permanent loss of her beloved object – a person, a place, a belief – and replaces it with another, redirecting all of the emotional energy once invested in it toward its successor. ‘[T]he beloved object no longer exists,’ Freud writes in Mourning and Melancholia (1917), and therefore ‘demands that the libido as a whole sever its bonds with that object’.

The melancholic person is divided between her ‘true’ self and the lost object residing, zombie-like, in her psyche

By contrast, in melancholy, which for Freud is mourning’s pathological, aberrant alternative, the initial loss cannot be acknowledged by the griever. In many cases, the loss is simply too shattering and profound to be countenanced, and is thus repressed, banished to the guarded but not impermeable fortress of the unconscious. This ‘[p]reservative repression’, wrote the literary scholar Nicholas Rand in 1994, ‘seals off access to part of one’s own life in order to shelter from view the traumatic monument of an obliterated event’. However, its confinement in the crypt of the unconscious – the ‘cocoon around the chrysalis’, in the evocative phrasing of the psychoanalysts Nicholas Abraham and Maria Torok in The Shell and the Kernel (1994) – doesn’t blunt the psychic pressure it exerts, the demand it continues to impose upon the would-be griever.

Instead, Freud believed that the melancholic individual processes this repressed debt and restitutes her lost object by becoming that object, taking it inside herself as a fully fledged, desiring subject in its own right, in this way psychically denying its real absence. ‘[I]dentification with the object,’ he writes, ‘then becomes the substitute for the love-investment.’ The analyst Melanie Klein wrote in 1935 that through this adoption, ‘the loved object may be preserved in safety inside oneself’. As the feminist theorist Judith Butler explained in The Psychic Life of Power (1997), ‘melancholic identification permits the loss of the object in the external world precisely because it provides a way to preserve the object as part of the ego and, hence, to avert the loss as a complete loss’.

Melancholy has a price: the melancholic person is divided between her ‘true’ self and the lost object now enjoying a zombie-like residence in her psyche; her psyche, in turn, willingly recruits itself as a servant to this phantom object in order not to be its mourner. In this way, Klein points out, melancholic incorporation is a potentially vitalising force. In Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism (2008), the literary theorist Jonathan Flatley coined the notion of ‘antidepressive’ melancholies – those, in other words, that ‘are the opposite of depressing, functioning as the very mechanism through which one may be interested in the world’. Indeed, as Freud himself began to intimate in The Ego and the Id (1923), published after his initial essay, melancholy might not even be so aberrant, but in fact the normal way that the self is formed – namely, from the adoption of things, beliefs and desires experienced but then abandoned. ‘The ego,’ writes Freud, the self, is merely ‘a precipitate of abandoned object[s]’ and identifications. We are, in other words, what we’ve lost.

If so, then are we perhaps seeing an enduring, melancholic relationship to the confinements and lockdowns initially created for our protection from the plague? Did this privation simply assume too great a role in our lives – as bearer and guarantor of security, indeed of life itself – to be replaced, at least so soon? Perhaps this psychological dynamic could make sense of many sceptical voices online who view with manifest cynicism Fauci’s announcements that travel and intimacy actually can resume post-vaccine, and that by early fall the US will be back to some version of normal.

Some degree of scepticism is warranted when it comes to ending lockdowns. After all, public health consensus has often gotten COVID-19 wrong. But maybe we are also clinging to a vision of safety because its removal feels like a threat.

In some ways, proof of this paradigm can be found in the cultural history of another epidemic – the HIV/AIDS crisis between the early 1980s and today. It has been said, if somewhat reductively, that that there are two halves to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, at least as it took shape in the global North. The halves are demarcated by the successful release in 1996 of highly active antiretroviral therapies, also called combination therapies or, more colloquially, the ‘cocktail’. These drugs unquestionably marked an inflection point in the pandemic, literally taking tens of thousands of people with AIDS off their deathbeds. They ushered in the era when, at least for the wealthy and those with medical insurance, HIV became simply another chronic and, in most cases, medically manageable condition. Life expectancy is no longer affected for the well-off by a diagnosis of HIV. And today, even transmission itself is increasingly rare, thanks to prophylactic drugs such as Truvada, or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). (Of course, even in wealthy countries like the US, many people – predominately trans people and those of colour – still contract and transmit HIV, still develop AIDS, and still die from it. For these people, there has been no ‘second half’ of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.)

But for the privileged, the first few years following the introduction of the cocktail saw the advent of a startling cultural development: the practice of barebacking and its subsets of bug-chasing and gift-giving, which refer to the abandonment of condoms and safe-sex practices. Many people, of course, had embraced unsafe sex throughout the first half of the epidemic. But barebacking proper, as an identity and, indeed, the centrepiece of a community, was a distinctly post-cocktail practice. It entailed the explicit eroticisation, even fetishisation, of HIV-positive semen. Some barebackers simply desired the risk of infection. Many made a point of not knowing either their or their sexual partner’s serostatus (the presence or absence of antibodies, as measured through a blood test technique known as serology). Others advertised their status as grounds for desire. Those who were positive (‘poz’), or at least claimed to be, might identify as gift-givers. Those who identified as negative might fashion themselves as bug-chasers.

Not surprisingly, the rise of barebacking subcultures triggered no shortage of pearl-clutching in the gay and straight press alike. Mainstream, heterosexual outlets predictably cast this practice as confirmation of the recklessly, even suicidally hedonistic nature of gay masculinity. For the more censorious in the gay press, the response was: after all the loss, this? For gay and straight observers alike, the fetishisation of HIV itself seemed perverse, an odd sort of Stockholm syndrome in its own right, an identification with an entity that had nearly wiped a generation of gay men off the face of the Earth.

To have sex in the presence of HIV means a return to the danger that has been queer culture’s defining tonality

By the mid-2000s, however, a small cohort of scholars had begun the work of re-evaluating these practices. In the hands of writers such as the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips and the literary scholars Leo Bersani and Tim Dean, barebacking was (re)cast as a type of gay self-fashioning made uniquely possible in a crucible of risk and lethality. For Dean, barebacking allowed gay men to practise a certain kind of kinship network – one with ancestors, descendants and siblings, as consanguineous as any family tree, and maybe more. As Dean writes in Unlimited Intimacy (2009):

sharing viruses has come to be understood as a mechanism of alliance, a way of forming consanguinity with strangers or friends. Through HIV, gay men have discovered that they can ‘breed’ without women.

Dean therefore does ‘not take for granted what might seem obvious, namely, that bareback subculture is all about death. For some of its participants, bareback sex concerns different forms of life, reproduction, and kinship.’

While barebacking in these accounts is about the proliferation of (gay) life rather than suicide, risk remained central to these encounters, too. ‘[Q]ueer sex,’ writes Dean, ‘may involve maximising risk rather than minimising it.’ It is about rejecting the privacy of the self as a defended, bounded entity and making it available to the Other.

This, for Dean, is what gay sex has always been about, and what went away in the first and more lethal half of the HIV/AIDS epidemic when safe sex reigned. To have sex in the presence of – if not in fact with – HIV for some means a return to the danger that has historically been queer culture’s defining tonality. And for the younger cohort of barebackers, many of whom didn’t live through the worst days of the HIV/AIDS crisis, this erotic culture allows them access to an experience they feel they have missed. Dean writes that the bareback sex scene can be understood as a ‘ritual summoning of ghosts’, a séance in which the barebackers become ‘interpersonal intermediaries … communicating and identifying with previous generations of the subculture’. As Bersani and Phillips put it in Intimacies (2008): ‘The barebacker is the lonely carrier of the lethal and stigmatised remains of all those to whom his infection might be traced.’ And in this way, we are challenged to think about ‘the privilege of being a living tomb’ (my emphasis).

I suggest that we think of barebacking and our strange melancholy at the prospect of a time after COVID-19 in much the same way. The first half of the HIV/AIDS epidemic was, like the COVID-19 pandemic, an objectively horrible era that obliterated huge swathes of human life and culture. In logical terms, it offers nothing – it is irredeemable. And yet, out of both plagues, new forms of human relation, culture and expression were born. Once these new idioms of human life are introduced, the prospect of abandoning them causes great pain, and is therefore vigorously resisted, even if they emerge from conditions of privation and loss.

To put this logic in more challenging terms, there is a resistance to losing loss itself. In the early and mid-1990s, even before the advent of barebacking, therapists, psychologists and leaders in the gay community were writing about the widespread incidence of friends and patients reporting depression over not having HIV/AIDS; see In the Shadow of the Epidemic (1995) by Walt Odets and A Crisis of Meaning (1996) by Steven Schwartzberg. Some of these accounts, to be sure, can be chalked up to so-called ‘survivor’s guilt’. But alongside that guilt was a sadness at not sharing in a defining experience of all the gay men around them. This, too, is a melancholy over the non-experience – the loss – of loss.

It isn’t only disease that provokes the melancholic response. Prisoners have been reported to miss prison. And Don DeLillo’s novel Underworld (1997) explores a similar phenomenon in fears over the ending of the Cold War. In a scene set in 1992, a character named Marvin Lundy, a compulsive collector of baseball memorabilia, tells an acquaintance, Brian Glassic: ‘You’re worried and scared. You see the Cold War winding down. This makes it hard for you to breathe.’

If the vulnerability of sex is – to be sure – pleasurable, it is also alienating, destabilising, uncomfortable

‘I don’t see the Cold War winding down,’ replies Brian. ‘And if I did, good. I’d be happy about it.’

‘Let me explain something that maybe you never noticed,’ says Marvin:

when the tension and rivalry come to an end, that’s when your worst nightmares begin. All the power and intimidation of the state will seep out of your personal bloodstream. You will no longer be the main … [p]oint of reference. Because other forces will come rushing in, demanding and challenging. The Cold War is your friend. You need it to stay on top … And when the Cold War goes out of business, you won’t be able to look at some woman in the street and have a what-do-you-call-it kind of fantasy the way you do today.

‘Erotic,’ replies a mystified Brian. ‘But what’s the connection?’

‘You don’t know the connection? You don’t know that every privilege in your life and every thought in your mind depends on the ability of the two great powers to hang a threat over the planet?’

‘That’s an amazing thing to say.’

‘And you don’t know that once this threat begins to fade? … You’re the lost man of history.’

In 1987, at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (and, for that matter, the Cold War), Bersani wrote: ‘There is a big secret about sex: most people don’t like it.’ His point here is similar to Dean’s. Both are saying that if the vulnerability of that act is – to be sure – pleasurable, it is also alienating, destabilising, uncomfortable. If we’re willing to hear it, then, our vaccine blues might have a lesson for us, too. The big secret of sociality, as learned on the back end of this newer pandemic, might be that we don’t want much of it, and that the capacity for ‘power and intimidation’, for ‘staying on top’, sexually or otherwise, might depend on threat.

To read more about the emotions, visit Psyche, a digital magazine from Aeon that illuminates the human condition through psychology, philosophy and the arts.