‘I wouldn’t show them the note,’ a retired nurse told my mother. It was a request to meet with my father’s physicians. He had undergone a cardiac surgery, and soon after became lethargic and difficult to rouse. The nurses thought he was simply fatigued from his procedure, and my mother didn’t want to question their professional judgment. Two days later, my father suffered an acute respiratory failure and was rushed to the intensive care unit (ICU). He was intubated and remained dependent on a respirator for days. The nurses told my mother that the doctors were considering a tracheostomy, but up to that point no ICU physician (called an ‘intensivist’) had so much as talked to my family.

Intensivists were not at the bedside during the limited visiting hours and, as they rotated, a series of different intensivists attended to my father. So my mother was left to wait outside the ICU in the remote chance that she would run into my father’s doctor, but nobody told her the name of the attending physician du jour, and the doctors’ faces were often hidden behind surgical masks as they walked the halls. So, with my help, she had drawn up the note, requesting a meeting. But it was to no avail. ‘The doctors might think your family is difficult,’ the nurse said.

I wondered why the doctors didn’t hold a family meeting to discuss my father’s prognosis and clinical options. While my mother wanted to speak to at least one of the intensivists, attempts to make appointments were met with reluctance. The nurses said the doctors were busy, that they had to uphold patient privacy and confidentiality. My mother started to blame herself for not insisting on further investigation regarding my father’s lethargy, and she was anxious about the lack of information. Worse, the insinuation that she would be bothering the busy clinicians for wanting a meeting with them intimidated her. She was sternly warned by a nurse not to overstay the visiting hours.

I am a bioethicist who has worked alongside clinicians in supporting patients and families making complex and rending care decisions. I have seen how physicians are bombarded with demands. Meeting with families requires not only coordination but energy: it is emotionally draining for clinicians to share grim prognoses with patients and families. But patients have a fundamental right to pertinent information regarding their illness. The doctrine of informed consent and related legislations in various jurisdictions require that adult patients be given relevant information about their conditions, and the risks and benefits of their care options, so that they can make decisions according to their values and goals. In situations where patients – like my father – might not have the mental capacity to make healthcare decisions for themselves, substitute decision-makers take that role on the patient’s behalf.

In many jurisdictions in the US and elsewhere, patients can legally appoint a healthcare agent or power of attorney who can make decisions for them if they lose such capacity. When no such person has been appointed, physicians themselves are expected to identify a surrogate decision-maker. It is generally assumed that family members or intimate associates are aware of a patient’s wishes and that most are concerned with their loved ones’ best interests. Getting family involved early on can clarify any misinformation as well as the goals of care. Most of all, involvement reassures everyone. It provides comfort at a tragic time.

My father was frail and delirious in the ICU. Being intubated and connected to monitors, he was unable to see, hear or speak. He had no glasses or hearing aid, perhaps because the care team worried that putting them on for him would interfere with his equipment. Or maybe they thought he wouldn’t need to see or hear, given that they weren’t going to directly communicate with him any time soon, so he was incapable of making or communicating his wishes.

My parents had been married for more than 45 years. Throughout all his illnesses, my mother was the informal caregiver for my father, tirelessly accompanying him to all medical appointments and helping him with medication, mobility – any and all personal care. Their lives and identities were intertwined. But now, for 22 hours a day, my mother was separated from her life partner by the walls of the ICU, wondering whether he was improving or declining, and lamenting that she could not be at the bedside to comfort him, especially when he appeared confused and agitated. With the ICU’s very limited visiting hours and no concrete information, she was isolated from my father, and he from her. Still, my father’s physicians had made no effort to meet with my family.

By this point, I was supporting my mother from afar. Having worked with many patients and families in end-of-life care, I was not afraid of a grim prognosis. I was more concerned about how my mother felt abandoned by a care team that was likely trying to provide what they considered to be the best clinical treatment for my father. I tried to comfort her, but she needed answers that only my father’s doctors could provide. My colleagues gave me general information about tracheostomy and associated risks. But despite my extensive bedside and research experience on navigating care decisions, I was unable to walk my mother through prospective treatment options for my father. Not only did we lack direct information from the care team, we weren’t even confident that the doctors would ask us to help make the treatment decisions. I could do little except urge my mother to continue nudging the nurses for as much information as possible, carefully observe my father’s presentation during her visits, and ask for a meeting with the doctors while I planned a trip to be with my family.

Having worked alongside clinicians for many years, I trusted the care team’s integrity and commitment to do what they believed would be in any patient’s – including my father’s – clinical interests. What I doubted was whether they would be able to accurately determine his overall best interests without involving our family in discussions about who my father was, his hopes and fears, and our understanding or concerns about various care options. After a couple more days of no response, my mother summoned the courage once again to give the nurses the note requesting a meeting with my father’s physicians. Eventually it worked. After I arrived, we met with an intensivist by my father’s bedside.

The first thing I did was assure the intensivist that we trusted the care team’s competence and that we knew they were doing their best for my father. I recognised that concerns about family involvement in Western medicine are partly due to the development of the concepts of individual self and autonomy in moral philosophy. From René Descartes to contemporary theorists, many Western philosophers consider the self as individualistic, independent and in control. This view of rugged individualism contrasts with – and, to some extent, refutes – the inherent significance of family relationships, which can include biological and adopted families as well as other domestic partnerships and intimate relationships. These relationships are characterised by collectivity, non-consensuality, sensibility and favouritism: much messier than the view of individuals being steadfastly in control of their own destiny.

According to rugged individualism, rational adults are separate from others by boundaries that can be justifiably breached only by the explicit and voluntary consent of self-determining subjects. Such individual boundaries support the patients’ moral and legal rights to give informed consent (or refusal) to various treatments without undue influence from others. In liberal societies, it is now generally accepted that patients are most invested in their own interests, such that they should be the ones to make voluntary decisions regarding their care. If my father were capable of making decisions, he would be solely authorised to receive information from his doctors regarding a tracheostomy or other care options, and to make his choices accordingly. If, however, he foresaw that he might lose his decisional capacity, he would have had to explicitly designate my mother, my brother or me, in advance, to be a substitute decision-maker.

‘They’re too emotional,’ one physician said. ‘They don’t understand what’s going on’

But for a couple who had been together for almost half a century, and with my brother also residing with them and taking on some of the caregiving duties, was such formal delegation really necessary to involve my family in the discussions and decision-making process? Certainly, for those who are fortunate enough to have family support at times of illness, many clinicians welcome varying levels of family involvement in patient care, especially when family members can provide emotional support to the patient, relay valuable patient information to clinicians, provide personal care while the patient is in hospital, or assist with discharge planning by assuming long-term care once the patient returns home. Nonetheless, family members are seen mostly as a means to the patient’s clinical ends, and are sometimes considered an intrusion in the professional caregiving space.

Our family was welcomed at the bedside when we could help soothe my flustered and bewildered father, but less so when we had questions about his fluctuating heart rates, even as my mother was the one who first noticed and reported my father’s lethargy a couple of days before his respiratory failure. While professionals usually recognise that building rapport with family members is essential for good patient care, many clinicians still experience uneasiness in dealing with families. (‘They’re too emotional,’ one physician said when asked about including families in decision-making. ‘They don’t understand what’s going on.’) Subtle doubts about family members’ qualification and motives for getting involved further strain relations between caregivers and families. This all makes some family members – such as my mother – very cautious in asking for information or being involved in the decision-making process.

In our case, the doctor seemed to think that since the team was contemplating a tracheostomy only if they couldn’t wean my father off the respirator, there was no need yet for a family meeting. After all, no urgent decision was required, and my father might regain decisional capacity during that time. My mother experienced herself as being strongly intertwined with my father, and I was confident that my father would want her to be informed and involved throughout, even if he were fully capable of making his own decisions. It probably never occurred to him that he would need to explicitly sign a legal document for his family to support him through the tough times. Nonetheless, contemporary healthcare continues to centre on individuals’ boundaries and to treat family involvement as non-ideal or even suspicious. In the autonomistic climate that thinks of patients’ identity in isolation from their social context, many clinicians worry that the voices and considerations of intimate others would ‘taint’ the care decisions.

While respect for patients’ self-determination is undeniably important, my experience accompanying many patients and families in making agonising healthcare decisions – and my own journey with my parents – has led me to believe that autonomy or individual agency is experienced, paradoxically, with others. Vulnerability is the reality at times of illness. My father couldn’t verbalise his concerns, but tears would flow as soon as we entered the room. Seeing him, I couldn’t help but wonder if the atomistic view of individuals as separate social units is false and impoverished. My father’s identities and values were rooted in his social and familial affinities with us, and such relational identity was central to his medical decision-making.

In an ageing US population with an increasing prevalence of chronic conditions, illness in contemporary medicine is often not an isolated or time-limited event. Healthcare decisions are shaped by one’s intimate others, and patients’ interests are rarely ever purely self-interested. My father had lived with his cardiac and respiratory illnesses for years and was cared for by my mother, such that his illness and care experiences evolved from their history and contributed dynamically towards its future. The same was evident in many patients and families I had worked with. Patients in tight-knit families often discuss their conditions and care with family members long before seeking professional help.

As my father’s hospitalisation prolonged, his identity shifted and disintegrated. Despite the rhetoric of patient-centred care, the structure, incentives and culture of the health system are often poorly aligned to respond to patients’ needs. My father was objectified in sterile settings governed by ‘foreign’ customs and rules. He was studied, tested and prodded by unfamiliar instruments in mechanical ways. He was not identified by his personal stories, histories or relationships, but primarily or even solely through bed or room numbers in the name of protecting patient anonymity, symptom-focused medical charts, and clinical jargons regarding diseased body parts. Visiting hours, diets, diagnostic schedules and discharge plans were determined not by his or our family’s preferences but by bureaucratic matters, lab or bed availability, cost-efficiency, professionals’ convenience, insurance coverage, and so on. While my father’s care team initially hesitated to meet with my family, presumably due to privacy and confidentiality concerns, the institutional care setting was anything but private. The hospital beds were separated by thin curtains. Patients and visitors could hear every moan and conversation from the other beds.

My mother is a reminder that patients such as my father are not mere collections of dysfunctional body parts

My father’s experience was not unique. With healthcare teams and division of labour, patients often have minimal contact with any particular provider and little continuity of care. As specialised medicine results in patients being attended by more clinicians than ever before, ‘care’ has ironically become increasingly impersonal and fragmented. Healthcare team members, especially in intensive care, are what the medical historian David Rothman has called ‘strangers at the bedside’ who usually focus only on their own specialised area. Well-meaning professionals are often overworked and attend to the patients only according to a very specific set of clinical and institutional circumstances. With the emergence of electronic health technologies, contemporary medicine has inadvertently exacerbated the isolation by reducing many patients with full histories and relational identities to quantified entities on dashboards.

Against this backdrop, family involvement helps to preserve or restore patients’ autonomous agency. Patients today are faced with complex data and choices, some of which are expensive and/or existentially tragic, such that those who are already burdened by illness and an unfamiliar medical culture might feel even more overwhelmed when they are expected to remember and analyse intricate medical information and make decisions on their own. Ironically, autonomous decision-making can lead some to feel more helpless and isolated. Even when patients are cognitively capable of participating in decision-making, such deliberation is often physically and emotionally exhausting rather than empowering.

So the patients’ priority might not be taking charge of their desires when they weave through the medical maze. Perhaps more important to some patients is the preservation of an overall sense of identity, agency and selfhood through connections with familiar others. Family members such as my mother – the constants in a changing plethora of health professionals – are reminders that patients such as my father are not mere collections of dysfunctional body parts or numbers on the digital dashboards that require professional interpretation and intervention. They are moral agents with full histories and deep relationships. Family involvement can preserve patients’ integrity and worth, rather than violate privacy or autonomous agency. Patients might prefer to entrust and defer decision-making to their family members or consider their interests extensively in the planning process. Since intimates generally care deeply about the patient’s interests and wellbeing, and likely have knowledge of the patient’s overall goals, family involvement enhances the patient’s agency.

For ethnic-minority patients in contemporary medicine, the concern over isolation is heightened. Some patients face language and cultural barriers, and might not be familiar with the specific healthcare system or Western medicine in general. They might also worry about breaking hierarchy and confronting their professional carers, who likely have little knowledge of the patients’ cultural and familial history. Ethnic minorities in the US might also lack adequate insurance coverage and depend on family members for medical care and advice. As family involvement is often integral to patients’ recovery and continued wellbeing, and as that familial caring relationship is in stark contrast to the service-for-hire model in institutional medicine, many patients might be inclined to trust their family’s judgment and seek their support in decision-making. These patients have been marginalised as ‘the other’ in clinical settings. Family involvement is helpful in preventing alienation and radical shifts in patients’ sense of identity and agency.

The rugged individualist framework ignores how a patient’s experience of illness has a tremendous impact on their friends and family. Indeed, the concerns and wellbeing of families is morally relevant in healthcare decision-making. My father’s illness and recovery experience were my mother’s life experience – they were intertwined and could not be separated. It was no surprise that soon after my father regained some cognitive function and was extubated from the respirator, he told my mother that he was terribly concerned about how his illness was burdening her emotionally and physically. Healthcare experiences highlight how our self is constituted by relations with others, and the responsibilities we have towards them. Even self-determining patients exist fundamentally in relation to others, such that patients’ interests might involve a dynamic balance among interdependent people who have overlapping concerns. Illnesses have very disruptive effects on family members, particularly on women, who are expected to provide various forms of care. Healthcare decisions are not simply individual affairs. My parents’ relationship should partly determine how my father’s medical needs would be met, as well as how our respective family members’ lives have to change to accommodate his care. Even as my father entered the professional care setting, our family remained an inextricable part of the processes.

Illness is a family matter. Familial care can be substantial in scope, intensity and duration. The family’s understanding, expectation and capacity to care for the patient are thus relevant to the treatment decision, both for its own sake and for the patient’s care pathway. As increasing institutional and systemic constraints can leave family members with no option but to take on an expanding range of care responsibilities, justice demands due attention to the impact that treatment decisions can have on family members. Inviting family members to be part of the decision process early on, and exploring their respective expectations and concerns, can help clinicians understand the patient’s overall context and to suggest the most appropriate care plan. In a society where women such as my mother are the primary carers, consideration of the impact that healthcare decisions have on intimates not only promotes patients’ overall agency, but also women’s wellbeing and moral status.

Certainly, a recognition of patients’ relational identity does not mean that all patients would want their family members involved in care decisions. Rather, a respect for patients’ relational identity and the family’s concerns requires that all parties keep the decisional space open. Such effort can clarify expectations and misconceptions. When we reframe familial involvement as one of a relational response to promote the patient’s identity and best interests, we can facilitate further strategies for collaboration, and promote patients’ and families’ wellbeing.

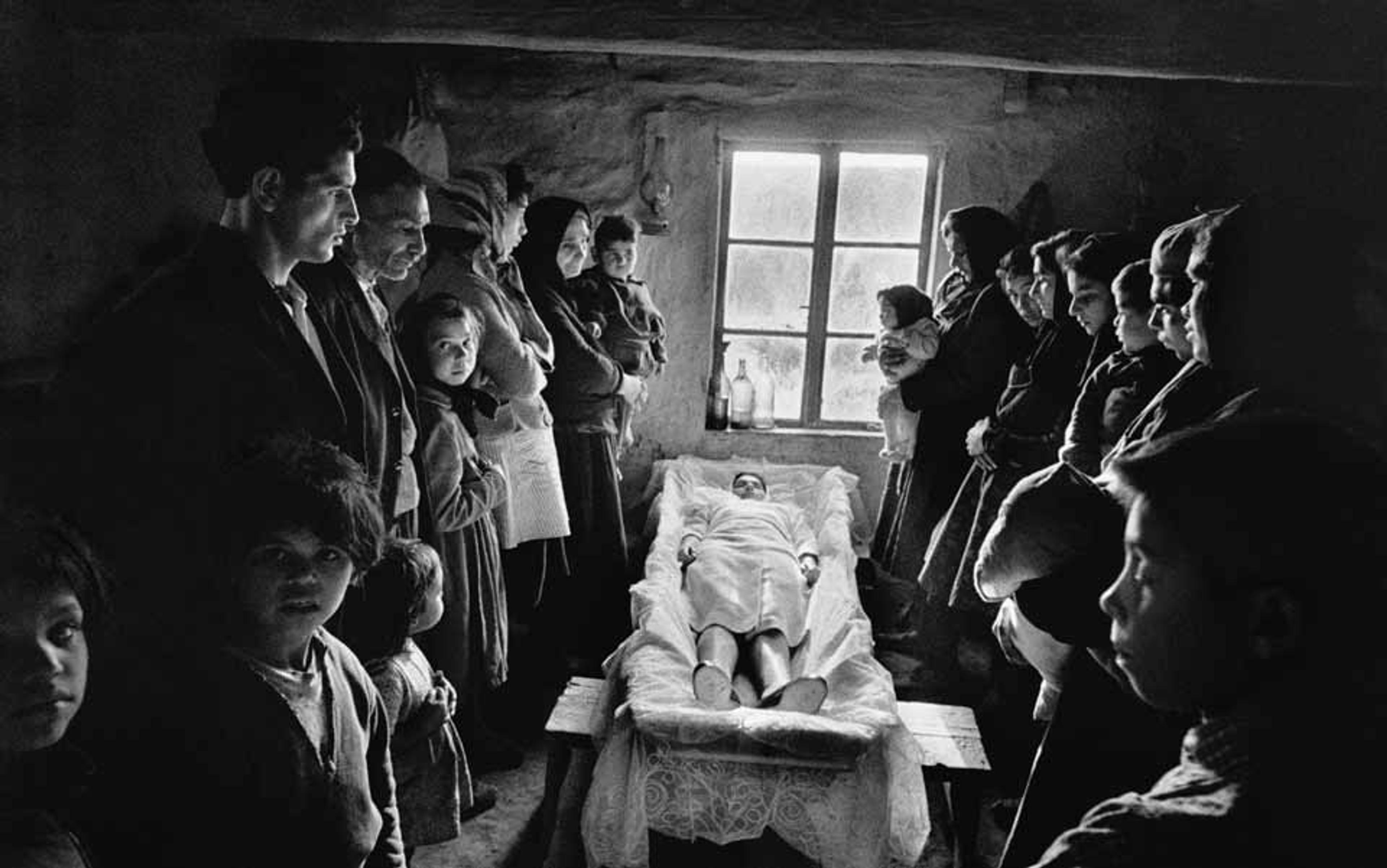

As my family’s struggle with my father’s final months showed me, after the farewell, the families are the ones who will live with the memories of their loved ones for their remaining days. How they cared for the patient in the process, and how the care team responded, would be part of their memories and narratives. How patients involve, connect with and protect their loved ones is also a crucial part of the patient’s wellbeing in their final journey. True respect for patients requires that we also honour the family’s involvement in decision-making: family-centred care is patient-centred care.