A cartoon from The New Yorker haunts me. Drawn with an economy of line that complements its subject matter, it depicts a Japanese couple wearing traditional dress standing in the doorway of their home. Before them is a rug with one of its corners flipped over. On it lies a toppled rice bowl, with chopsticks askew on the floor. ‘Oh no,’ exclaim the couple. ‘We’ve been ransacked!’

The joke was always on me. Much as I admire a clean surface, I have never been a minimalist. But arriving at middle age on the brink of my very own economic meltdown, I’m having to question my relationship to things, asking: why are they so important? What do they signify? Could I live without them, or make do with a cyber version – a clutch of Pinterest boards and a library of ebooks?

In some ways, it was an attachment to things that undid me. If I had been quicker to accept that my marriage was doomed, perhaps I would not have used a modest inheritance to buy our second-hand Mini, or to pony up the down payment on our flat. And perhaps I’d have hired a better divorce lawyer. As it was, I paid my ex to give up his claim on our home. I didn’t move, because having weighed the options I realised I could only go down the property ladder. Besides, having already left my country, I wasn’t prepared to give up the home I’d invested so much in: I thought I was sensibly securing my future, not imperilling it by tying myself to an obligation.

I held my own for years, until the newspaper employing me eliminated numerous jobs, including mine. Now, with the redundancy money gone, I have resorted to selling things. I take every small job I can; I apply for bigger jobs; occasionally, I have lodgers. Mine is not a hardscrabble life, though it’s fast heading that way. The wolf at the door has me by the lapels and is pushing me into a corner of my beautifully overstuffed flat.

The trouble is that I am my things and my things are me. I don’t want to relinquish them. This reluctance is not acquisitiveness: it is that I don’t want to abandon myself. Single, childless, I’m all I’ve got: me – and the accumulated external markers of who I am, which are also narrative prompts for the ongoing story of my life. These stories connect me to the past, present, future, and live in nearly everything I own. Those oak tables in my living room come from a Maryland junk shop; embedded in their grain is the story of my bribing friends with a promise of crab cakes in exchange for help transporting the furniture back to New Jersey. A kitschy dish shaped like a duck taking flight reminds me of researching a book in Nashville. The bisque Rosenthal vase shouts: ‘Get back to Berlin’ every time I dust it.

In Being and Nothingness (1943), Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that man wishes to possess things in order to enlarge his sense of self, and that we can know who we are only by observing what we have. Studies of ownership and identity – by marketing experts, anthropologists, psychologists and sociologists – come to the same conclusion: we project our sense of self onto everything we own. According to Russell Belk, a professor of marketing at York University whose 1988 paper about possessions and the extended self remains a touchstone for all subsequent research, this kind of projection serves a valuable function for a healthy personality, ‘acting as an objective manifestation of self’. Humans have a fundamental need to store memories, values and experiences in objects, perhaps to keep them safe from memory loss; proof that, yes, that really happened.

It is not even necessary to own these totemic items for their charge to hold. People speak about ‘my’ television programme, ‘my’ movie star, or ‘my’ seat in a classroom – a form of possessive self-definition that extends to matters of taste as well as to stuff. Questions such as: ‘Are you Beatles or are you Stones? Blur or Oasis?’ are examples of how taste funnels us into tribes that proclaim our aspirations and ideals along with our interests.

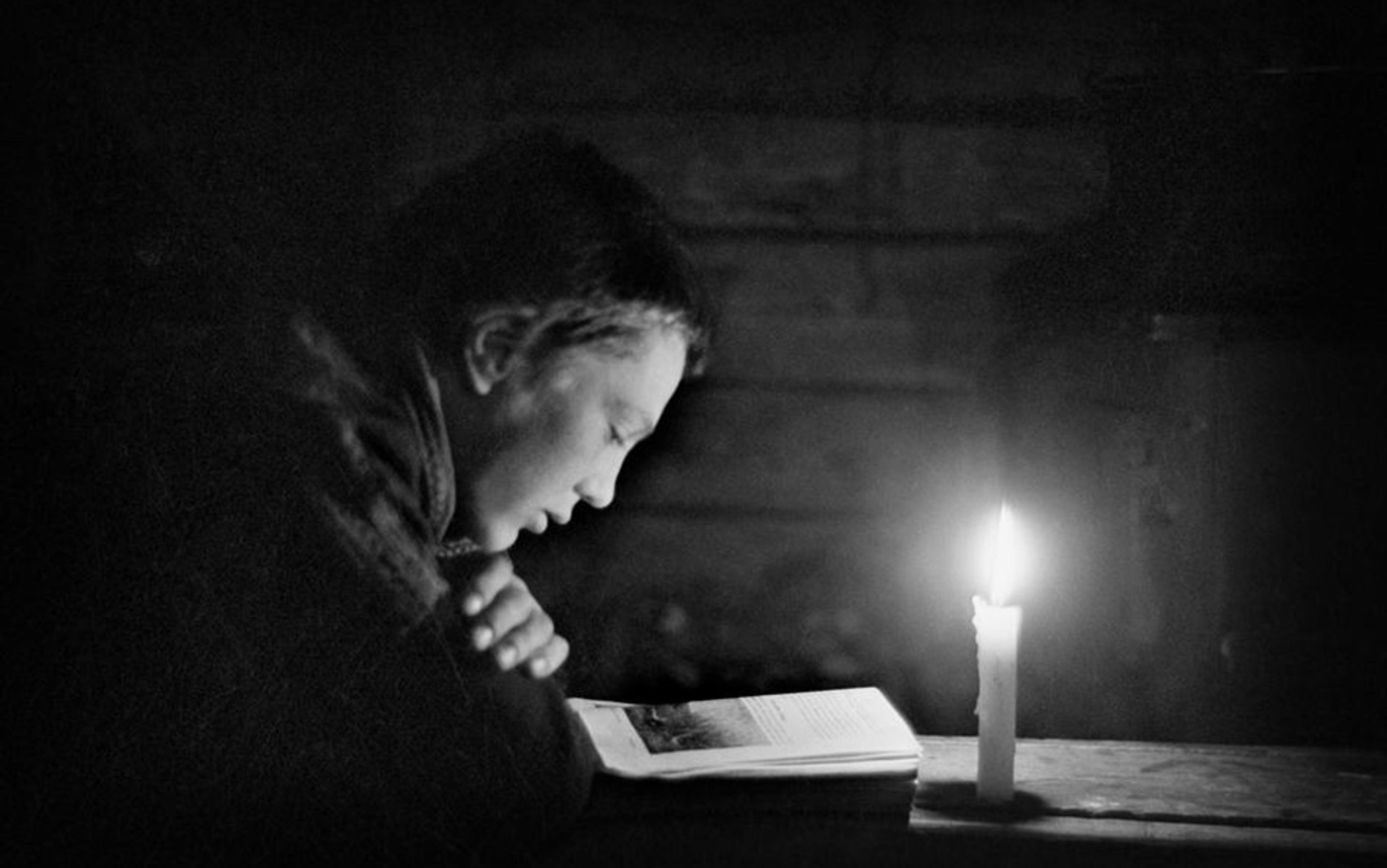

Who are my people? Open my front door and the first thing you notice are books. They line the walls, hover overhead, and stack up on tables. Each is a chunk of autobiography, a clue to who I was while reading it, what I found to love inside its pages and where it sent me next. Umberto Eco understood this phenomenon well, saying: ‘The contents of someone’s bookcase are part of his history, like an ancestral portrait.’

Following my marriage to a native in 1997, I moved to Scotland. At the time, I shipped plenty of clothes, furniture, art and bric-a-brac but stored my books with a relative. It felt like an amputation and, thereafter, phantom library syndrome haunted me. I’d reach for a book – to check a quote, prove a point, seek comfort – and grab air. After an agonising year of longing, I sent for my library. Only when it arrived did I feel whole, and wholly emigrated. The years haven’t blunted the pain of those emotions: and if that’s how lost and unhappy I felt without my books, I don’t imagine my psyche holding up well minus them and more.

Every inch of my Victorian-era flat – with its paintings done by friends, its old furniture, its colourful 20th-century pottery and stacks of the inexpensive, mass-produced glassware manufactured during America’s Great Depression – telegraphs that I look to history for inspiration and enlightenment; testifies to the importance of literature and art in the formation of my psyche.

As I contemplate a possible future of enforced minimalism, I am unsettled by the words of the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who wrote in ‘Why We Need Things’ (1993) that: ‘Artefacts help objectify the self … by demonstrating the owner’s power.’ They ‘reveal the continuity of the self through time, by providing foci of involvement in the present, mementos and souvenirs of the past, and signposts to future goals… objects give concrete evidence of one’s place in a social network as symbols… of valued relationships.’ As such, they stabilise our identities, giving permanent shape to ourselves ‘that otherwise would quickly dissolve in the flux of consciousness’.

I fear that disposing of my possessions would dissolve me. I’m precariously balanced on an emotional seesaw. On one side, writ large, are phrases such as ‘check your privilege’ and ‘first-world problems’, which remind me that many endure far worse. On the other side is the gut-wrenching sensation that I’m being erased. I try projecting myself into an unfettered future of ease and liberation. But all my imagination conjures is the kind of grim bedsit existence depicted by Muriel Spark.

Perhaps I ought to take heart from the British artist Michael Landy, whose fortnight-long live artwork Break Down (2001) consisted of him destroying all of his 7,227 belongings. ‘I am always trying to get rid of myself so that I can move on,’ he’d said. I was struck by a number of aspects of Landy’s project. First, he was possession-free for about 10 minutes only, until someone gave him a Paul Weller CD. He could have refused the gift, but didn’t. Second, the things that meant most to him he left until last to destroy. The final item was his father’s sheepskin coat, which he not-so-secretly hoped someone would steal before it was shredded. Landy told The Guardian: ‘I really felt I was jinxing my dad by destroying it.’

Reflecting on the experience later, Landy told the Independent: ‘What I had done was so destructive and nihilistic; for about a year I didn’t make any art. I didn’t do anything.’ This sounds to me as if he temporarily lost his sense of self. At the very least, it suggests a period of psychological recalibration: here’s a blank slate. What, if anything, will you write on it?

Sophie Woodward, a lecturer in sociology at Manchester University, works on a research project called Dormant Things. She studies the items that people store in cupboards and attics, and which they often never use, but which have ‘implications for understanding memories, life and relationship changes, and also for developing more sustainable consumption’. Time and again, Woodward notes that people think they ought to get rid of stuff; but, she tells me: ‘The more I talk to them, the more I realise that they get immense pleasure out of having those things, even things they don’t look at, because when they do it reminds them of something.’

You can be held to ransom by the things you cling to. The journalist and television presenter Aggie MacKenzie fronted Storage Hoarders (2012-), the ‘clutter-busting’ British TV programme that helped people who were spending fortunes on maintaining expensive storage facilities, or whose garages and garden sheds were entirely full of dormant things. She told me: ‘For some, [it’s] almost a guarantee against death: if my stuff is here then I’m here. For [others] there’s a sense of “one day it’ll come in handy”. Stuff also maintains the status quo: nothing awful can happen if everything stays the same.’

In a 2015 episode of BBC Radio 4’s Thinking Allowed, Woodward said that we struggle to get rid of things because they’re redolent with meaning. For example, most women hang on to shoes they don’t – and can’t – wear. People are unwilling, said Woodward, ‘to relinquish the possibility that they could, it’s the person they think they could be, which is why they kind of keep them’. I admit that this is a factor in my life. No one needs four glass vanity sets. I don’t own a single dresser to display them on. But I’ve always yearned for a rambling house, and these old-fashioned objects likely represent its bedrooms. Discarding them would mean drawing a line through my dream once and for all. Yet keeping them reminds me that a woman’s reach should exceed her grasp. And I love looking at them, love being the person who collects this thing.

our psyches need the stability that possessions bring

That is not the same as trying to outwit the Grim Reaper. I accept that I’m finite and, at 56, understand that I have less future than past. My nearest family is in Dallas. My stuff means nothing to them. Wouldn’t it be helpful to get rid of everything now? But why, argues my Ego? There’s little point in circumscribing my life and diminishing my personality as a courtesy to others.

Anecdotal evidence reinforces my instinct that jettisoning everything would undermine my me-ness. Daniel Miller, an anthropologist at University College London, spent 17 months conducting interviews with 30 London residents for his book The Comfort of Things (2008), in order to explore ‘the role of objects in our relationships, both to each other and to ourselves’. He was testing the popular assumption that ‘our relationships to things [come] at the expense of our relationships to people’.

He discovered that this assumption wasn’t true: ‘usually the closer our relationships are with objects, the closer our relationships are with people’. One of his most unsettling encounters was with a man who owned nothing, living – perching, really – amid a minimum of donated furniture and clothes. ‘There is a loss of shape, discernment and integrity. There is no sense of the person as the other, who defines one’s own boundary and extent.’ This seems to support Csikszentmihalyi’s belief that our psyches need the stability that possessions bring.

That grounding and containing sensation is then cemented by interaction. Even as a child, I would rearrange my belongings to see things in new spatial relationships. The habit persists. I rearrange and de-clutter when I feel stagnant. It’s my soothing, sure-fire cure for psychological constipation. Or is there another reason for this behaviour? Some psychologists say that we love possessions because we can control them, whereas we can’t control people. It’s true that when my marriage broke up and my husband left, I reconfigured furniture obsessively for the best part of two years, reclaiming the space, reclaiming myself – washing that man right out of my hair, through the medium of interpretive decorating.

Marc Allum understands how possessions relate to our multiple selves. Familiar to many people as an expert on the long-running British TV programme Antiques Roadshow, he’s also a freelance writer and broadcaster, and consults with auction houses and private collectors. He adores finding and living with objects representing thousands of years of history, and told me: ‘We’re made to feel guilty for owning things. I stopped apologising many years ago, because I realised that if I did not surround myself with things I couldn’t justify my own existence. My career wouldn’t exist without the objects.’

Allum is no hoarder, but he has masses of stuff, and admits: ‘What worries me, and this might sound strange, is the ongoing insecurity of losing it all.’ And if he did? ‘The objects are you in a sense, and not you, but you can’t do without them. A relative said: “Don’t you know that the stuff in your house is worth enough for you to retire for the rest of your life?” I said: “All I would do with the money is start over again.” Even if I wound up living in a hut on the beach, the beach would turn into my collection. Every day it would give me another opportunity to pick up a more interesting bit of driftwood.’

I understand this impulse. Each determined exit is offset by an entry. Dozens of books depart but new ones arrive with every post. I sell a vase but an antique tablecloth pops up in its place. If you held a gun to my head, insisting that I choose my single most important possession, I’d probably let you shoot me. What I don’t know is whether this means I have a slippery grip on my identity, or an iron one.

I think of 1997, when I moved to Scotland, as a time of great dispersal and reinvention, but closer examination exposes this as self-delusion. What got jettisoned was minimal: appliances with US plugs, a bed, a sofa, my vintage hat and eggbeater collections, and a beautiful old set of scales. Everything else I shipped over from the US – I had money to indulge myself then. If I have to sell my flat now, I’ll likely wind up in one small room or squatting with friends. I can’t afford storage.

Which brings me to a last, shaming truth. While I don’t buy high-cost, high-status items, my pride in what I possess is linked to a desire for admiration and love. I hope that people visiting my home will get me in a way that’s not possible when meeting me elsewhere. What’s more, this happened: my ex-husband swore that he fell for me when he saw my library and the dictionary that lives by my bed. Yet I’d need a nonstop stream of visitors to justify my numerous possessions. Why do I persist in playing to an imaginary audience, like a fairy tale princess in suspended animation, waiting to be discovered? Perhaps the dream of an improved future self keeps us whole and functioning in the here and now. Perhaps this is the necessity.

without objects anchoring me and providing pleasure, I fear I’d fly off the face of the Earth

Yet if admiration and fantasy were of paramount importance to my psychological wellbeing, surely I could just transfer my dust-collecting, costly-to-house stuff to digital warehouses, and live happily ever after. With thousands of followers on Twitter, hundreds on Pinterest, and traffic to my blog, the audience for my sensibilities is greater than ever – and I don’t even have to put the kettle on. I could shift my library to ebooks, my music collection to a streaming service, while keeping only the umbilical computer link to my life and loves.

That’s the theory. It is a bleak, soul-shrivelling prospect to me, though it has proven effective for some. Woodward says: ‘I spoke to a woman who’s a de-clutterer and who trained as a visual anthropologist. She takes videos of people’s homes before they get rid of stuff. It’s helpful, because it’s not like their things are gone completely. They are still marked, so that’s a kind of presence.’ Yet in the next breath she contrasted this woman with another with whom she went through boxes of stored items from her childhood. ‘You could see her having memories as she looked at each thing. That would never have been captured if she’d been looking at a photo. Stuff is an archive of our lives.’

Though digitally-savvy, I remain object-bound. I suspect it’s my age. I use my Kindle only when travelling, listen to CDs, and don’t see the point of moving my old photos onto the cloud – throwing away a portrait feels like murder. Even in the scholarly community, the jury’s out: this technology is too new for definitive conclusions about whether digital possessions work as well as their material counterparts in cementing identity over time.

Were I to live without my stuff, I’d have the same intellect, the same memories, values and beliefs that I hold now; but, without objects anchoring me and providing pleasure, I fear I’d fly off the face of the Earth. I know I’d be a miserable version of that self, endlessly muttering: ‘I used to have one of those.’ As Belk reminds us, people entering the military, religious orders, concentration camps, prisons and other institutions have their personal possessions removed immediately, to eliminate their uniqueness.

Shorn of my possessions, I would still be me. But, I suspect, not for long.