In March 1945, Leatherneck Magazine, an official organ of the United States Marine Corps, published a brief, ostensibly humorous article describing a parasite named Louseous Japanicas. It included an illustration of a grotesque creature with stereotypically Japanese features. The accompanying text tells us that:

To the Marine Corps, especially trained in combating this type of pestilence, was assigned the gigantic task of extermination… Flame throwers, mortars, grenades and bayonets have proven to be an effective remedy. But before a complete cure may be effected the origin of the plague, the breeding grounds around the Tokyo area, must be completely annihilated.

Later that same month, US warplanes dropped 2,000 tons of incendiary bombs on the city of Tokyo. The stench of burning flesh was so intense that fighter pilots reached for their oxygen masks. Over the next five months, at least half a million Japanese men, women and children were, in the words of the US Air Force General Curtis LeMay, ‘scorched and boiled and baked to death’ in the firebombing of 67 Japanese cities. And then there were Hiroshima and Nagasaki…

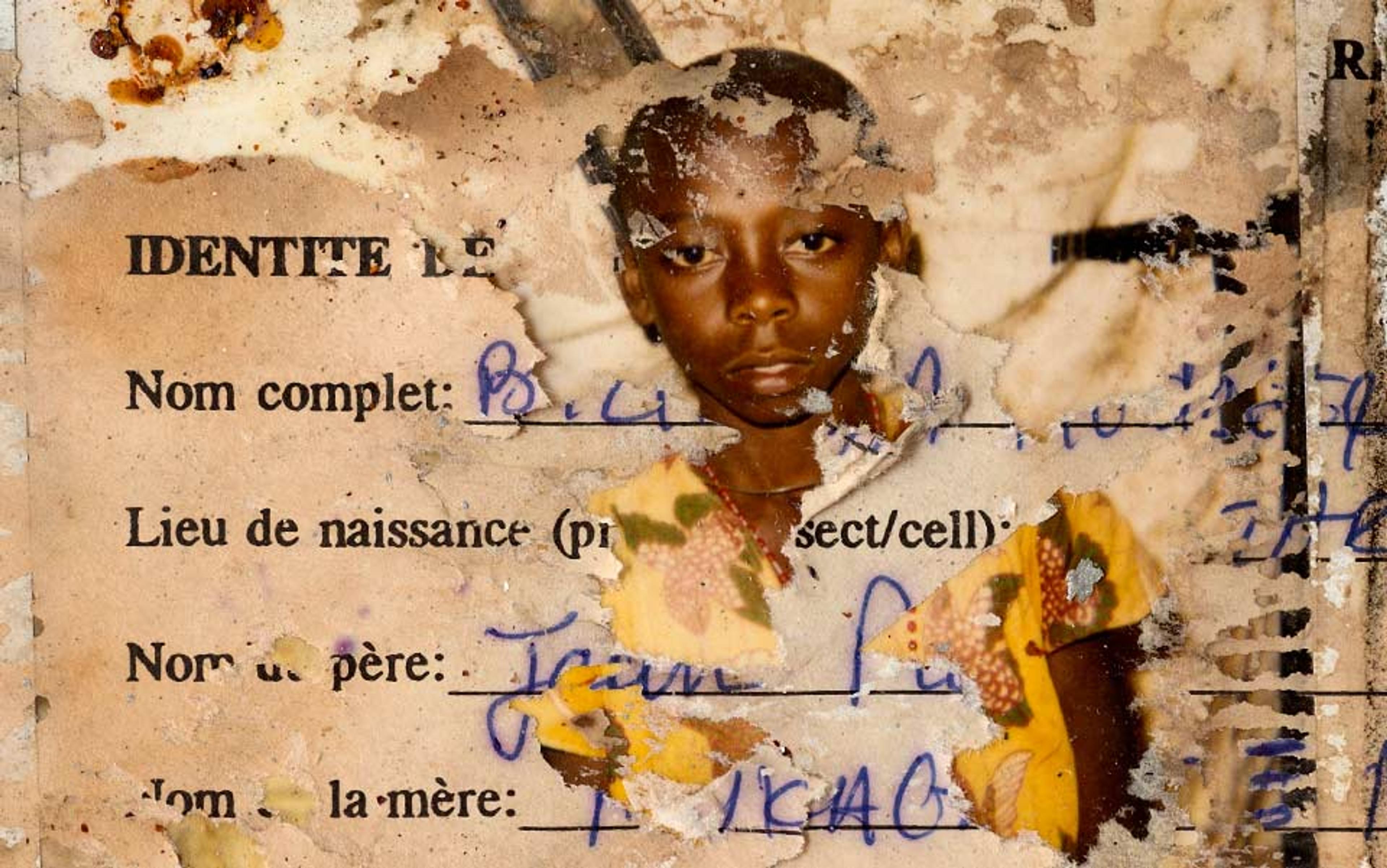

Only a few years earlier in Germany, Jews were labelled Untermenschen (subhumans) and were likened to vermin, maggots and disease-transmitting parasites. Half a century later in Rwanda, Hutu génocidaires referred to their Tutsi quarry as cockroaches and snakes. This year, the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu characterised the Palestinian killers of three abducted Jewish teenagers as predatory beasts (an epithet that he did not apply to the Jewish extremists who burned a Palestinian boy alive in retribution). ‘They were kidnapped and murdered in cold blood by animals,’ he said. ‘Hamas is responsible and Hamas will pay.’

What is the common element in all these stories? It is, of course, the phenomenon of dehumanisation. But this is neither recent nor peculiar to Western civilisation. We find it in the writings from the ancient civilisations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and China, and in indigenous cultures all over the planet. At all these times and in all these places, it has promoted violence and oppression. And so it would seem to be a matter of considerable urgency to understand exactly what goes on when people dehumanise one another. Yet we still know remarkably little about it.

Here’s what we can say. The term ‘dehumanisation’ has acquired a variety of meanings since its introduction in the early 19th century. Some people think of it as a derogatory language-game: the rhetorical practice of likening human beings to non-human animals or inanimate objects. Others understand it as the act of degrading others by subjecting them to cruelties or indignities. Still others believe that we dehumanise people by denying them subjectivity, individuality, agency or other quintessentially human characteristics. My focus is on a different conception of dehumanisation – a deeper one that typically underpins all the others. We dehumanise other people when we conceive of them as subhuman creatures. Dehumanisers do not think of their victims as subhuman in some merely metaphorical or analogical sense. They think of them as actually subhuman. The Nazis didn’t just call Jews vermin. They quite literally conceived of them as vermin in human form.

Look at how European settlers thought about the Africans whom they enslaved. As the US historian of slavery David Brion Davis remarks: ‘It was this extreme form of dehumanisation – a process mostly confined to the treatment of slaves and the perceptions of whites – that severed ties of human identity and empathy and made slavery possible.’ The writings of Morgan Godwyn, a 17th-century Anglican clergyman who campaigned relentlessly for the civil rights of Africans and Native Americans, throw considerable light on how English colonists thought about their putatively subhuman slaves. In The Negro’s and Indians Advocate (1680), he wrote that he had been told ‘privately (and as it were in the dark)… That the Negros, though in their Figure they carry some resemblances of Manhood, yet are indeed no Men.’ ‘They are,’ he continued, ‘Unman’d and Unsoul’d; accounted and even ranked with Brutes’ – ‘Creatures destitute of Souls, to be ranked among Brute Beasts, and treated accordingly.’

This pattern of thinking has been reproduced with spine-chilling fidelity across time and space, and from one historical epoch to the next

It is instructive to compare Godwyn’s account with a much more recent example of dehumanising discourse. Der Untermensch (‘the subhuman’) was a pamphlet published in 1942 under the editorial direction of Heinrich Himmler, the Nazi responsible for setting up the concentration camps, and it presented Jews as ravenous subhuman predators. ‘Not all of those who appear human are in fact so,’ the authors warned. Jews were not human beings, but rather ‘beasts in human appearance’ that were ‘lower on the spiritual and psychological scale than any animal’.

Although separated by centuries, these two mindsets – the colonial and the Nazi – are astonishingly similar. Both claim that the human appearance of certain groups belies their true nature. So, apparently, while Africans and Jews display all of the outward marks of humanity, deep down, where it really matters, they lack that special something that makes one human; their humanity is only skin-deep, concealing a subhuman core. This pattern of thinking has been reproduced with spine-chilling fidelity across time and space, from culture to culture, and from one historical epoch to the next. Its sheer pervasiveness suggests that it reflects something fundamental about the human mind.

Investigations into the phenomenon of psychological essentialism cast a powerful light on the psychological wellsprings of dehumanisation. The philosophical doctrine of essentialism (the belief that there are essences) has a lengthy history stretching back at least as far as Plato and Aristotle. The essence of a thing is supposed to be whatever property or properties it has that make it the kind of thing it is. Consider a wedding band fashioned from pure gold. What makes it the case that this chunk of matter is a piece of gold? Philosophers have pointed to the fact that it possesses the essence of gold. Its essence lies in its microphysical structure: a substance counts as gold if and only if the atoms from which it is composed have precisely 79 protons in their nuclei. It’s because every atom of gold has 79 protons, and every atom with 79 protons is an atom of gold, that the atomic number 79 is the essence of gold.

The Reverend Godwyn’s contemporary, the English philosopher John Locke, was an important contributor to the theory of essences. He distinguished between real essences and merely nominal ones. Nominal essences are ordinary, commonsensical concepts of kinds of things, whereas real essences are deep, unobservable properties that make a thing a member of a kind. The real essence of gold, hidden in its atomic structure, is inaccessible to casual observation, but its merely nominal essence is simply a list of the descriptors that we ordinarily associate with gold (heavy, yellow, precious ductile metal, etc). ‘Essence may be taken for the very being of any thing, whereby it is, what it is,’ wrote Locke in 1689, ‘And thus the real internal, but generally in Substances, unknown Constitution of Things, whereon their discoverable Qualities depend, may be called their Essence’. He warned, however, that ‘if you demand what those real essences are, it is plain men are ignorant and know them not … and yet, though we know nothing of these real essences, there is nothing more ordinary than that men should attribute the sorts of things to such essences’.

What is it that makes a porcupine? It’s not its quilly appearance. A mutant porcupine without quills is a still a porcupine

Nearly 300 years after Locke had penned those words, the notion of real essences got up from the philosopher’s armchair and entered the laboratory. In 1989, the psychologists Douglas Medin and Andrew Ortony, both at Northwest University in Illinois, coined the term ‘psychological essentialism’ to denote our pervasive and seemingly irrepressible tendency to essentialise categories of things. Since then, researchers have accumulated a sizeable body of empirical evidence that humans are natural-born essentialists. We are disposed to think of the world as carved up into discrete kinds of things, each of which has a real essence.

Biological species are a good example. People the world over segment the animal kingdom into species. But what makes an animal a member of a certain species? What is it that makes a certain creature a porcupine? It’s certainly not its quilly appearance. A mutant porcupine without quills is a still a porcupine. Psychologists and cognitive anthropologists have shown that people tend to believe tacitly (and sometimes explicitly) that what makes an animal a member of a certain species is not its outward appearance but rather some deep fact about it – in this case, the porcupine essence – even though we might have no coherent idea of what that essence consists in (recall Locke’s insight that ‘it is plain men are ignorant and know them not’).

To appreciate how effortlessly we bisect the world into outward appearance and inner reality, one need only consider cinematic portrayals of vampires. Under most circumstances, vampires are indistinguishable from genuine human beings. You might strike up a conversation with one in a bar without having any suspicions at all, until the moment she sinks her fangs into your throat. Cinematic vampires are ersatz humans because they lack the inner spark that that all human beings supposedly share. I doubt that many people find this difficult to wrap their minds around. Likewise, the first audiences of A Midsummer Night’s Dream had no trouble understanding that though Bottom’s head looked like that of a donkey, he was really a human being ‘on the inside’, the donkeyish appearance concealing the human essence.

The phenomenon of psychological essentialism explains how we are able to think of others as non-human creatures despite all appearances. But it gives us no purchase on the crucial issue of subhumanity. When we dehumanise others, we do not simply regard them as non-human. We regard them as less than human. Where does that come from?

The notion of subhumanity obviously involves a hierarchy. It implies that kinds of beings are ranked on a scale from lower (in some sense) to higher (in some sense). This hierarchy is one of intrinsic value – the value that a being has in and of itself. Attributions of intrinsic value are intimately bound up with beliefs about moral obligation. The more of it something has, the greater the moral consideration we owe to it. Human lives are typically characterised as supremely valuable, an assessment that contrasts sharply with views about the value of the lives of cockroaches. Consequently, we grant people a moral status that we deny to cockroaches. We feel free to crush the latter underfoot, but it is a moral transgression of the highest order to treat our fellow human beings the same way. During the 1994 Rwanda genocide, militant Hutus characterised their Tutsi neighbours as inyenzi – cockroaches. And this made it permissible, even obligatory, to slaughter them.

One might slit a pig’s throat and roast it over a fire, but it would be abhorrent to do the same to an infant

A version of this cosmic hierarchy found formal expression in the Middle Ages as ‘the Great Chain of Being’. God, the supremely perfect being, stood at the summit of the Chain, while every other kind of being was placed at a rank commensurate to its distance from the Creator. With characteristic immodesty, we humans placed ourselves a little below the angels, but higher than non-human animals. Non-human animals, plants and minerals all occupied more lowly ranks, and were therefore considered to be subhuman.

Historians tell us that the idea of a Great Chain of Being sprang from a philosophical tradition with roots in ancient Greece. But the vision of the cosmos as a vast moral hierarchy is far more ancient, pervasive, and deeply ingrained in our moral psychology than that. This is hardly surprising. After all, human social life would be impossible in the absence of moral distinctions. In every human society, there are moral imperatives requiring certain kinds of thing to be treated differently from others. There is no human society in which it is permissible to treat a member of one’s community in the same way that one would treat a weed, a parasite, or an animal that is hunted for its flesh. One might slit a pig’s throat and roast it over a fire, but it would be abhorrent to do the same to an infant, because babies are ‘higher’ (that is, more intrinsically valuable) on the scale than pigs.

This aspect of our moral frameworks stokes the fires of dehumanisation, because it allows us to think of other people as creatures ranked lower on the cosmic scale than we are, and thus permits us to deal with them in ways that do not befit fellow human beings. Recall Godwyn’s words: Africans were ‘ranked among brute beasts and treated accordingly’.

One important question about dehumanisation has not yet been answered. What function, if any, does it have? The answer surely lies in our peculiar ambivalence about violence. Homo sapiens is a supremely social species. Our remarkable capacity to co-operate with one another has secured our dominance of the planet. For our hypersocial species to survive, we have had to acquire immensely powerful inhibitions against doing violence to one another. It’s easy to overestimate the ease with which humans commit violence to humans. Even in Honduras, currently the homicide capital of the world, there are a mere 90.4 killings for every 100,000 citizens (a murder rate of only 0.09 per cent).

People even have difficulty killing in circumstances where they are rewarded for doing so. As the US Army combat historian Brigadier General S L A Marshall tellingly observed in Men Against Fire (1947): ‘The average and normally healthy individual – the man who can endure the mental and physical stresses of combat – still has such an inner and usually unrealised resistance to killing a fellow man that he will not of his own volition take life if it is possible to turn away from that responsibility … At the vital point he becomes a conscientious objector, unknowing.’

we have developed methods to circumvent and neutralise our own horror at the prospect of spilling human blood

If all this is true, then why has human history been so bloody? Why has history been littered with corpses for at least the past 10,000 years? Looking around the world today, why is a brutal war raging in the Syria and a genocide of attrition running its gruesome course in Sudan? Why are more people enslaved today than was the case at the height of the transatlantic slave trade?

The sad fact is that acts of violence often promise to deliver certain benefits. By waging wars, implementing genocides or enslaving vulnerable populations, we can acquire resources that would have been difficult or impossible to get by gentler means. Consequently, clever primates that we are, we have developed methods to circumvent and neutralise our own horror at the prospect of spilling human blood. We have constructed and disseminated toxic ideologies, ingested mind-altering drugs and engaged in powerful collective rituals, all for the sake of disinhibiting aggression and directing it against our neighbours.

These techniques of behavioural engineering are complemented and reinforced by psychological processes, the most potent of which is the dehumanisation of those whom we wish to harm. In dehumanising others, we banish them from the magic circle of moral consideration. Our inhibitions against harming them are thereby disabled. This frees us to dispose of them to suit our own purposes.

Dehumanisation has been a feature of social life since the beginning of civilisation, and it remains the source of enormous suffering. But despite its overwhelming importance, there has been little effort devoted to studying it. In fact, to the best of my knowledge there is not a single university department, government agency or non‑governmental agency that is specifically devoted to investigating the dehumanising process. Perhaps part of the problem is that we have tended to think that dehumanising others is exclusive to moral monsters such as Hitler and Pol Pot. But this isn’t true. Dehumanisation is the upshot of certain features of our normal psychology which can lead us down the road to acts of appalling violence and cruelty. You don’t have to be a monster or a madman to dehumanise others. You just have to be an ordinary human being.

Research into the phenomenon is almost entirely confined to social psychology. It’s obvious that psychology has an important part to play in developing a comprehensive theory, but it is equally obvious that psychology can’t deliver such a theory all on its own. The investigation of dehumanisation needs to be a multidisciplinary enterprise, for it requires us to address questions not only about the human mind but also about ideology and propaganda, history, politics and culture, our fraught relationships with non-human organisms and the deep structure of our conceptual frameworks.

dehumanisation plays a key role in fomenting genocidal violence

So research into dehumanisation is still in its infancy, and the theoretical synthesis envisioned in the preceding paragraph is nowhere near becoming a reality. Strangely (in light of widespread agreement that dehumanisation plays a key role in fomenting genocidal violence) there is not a single research centre anywhere in the world that is specifically devoted to investigating its causes and dynamics. Questions about it are plentiful but resources for answering them remain thin on the ground.

Thanks to concerted efforts by medical scientists, we have managed to tame diseases that were once scourges of humanity. Smallpox, a disease that was responsible for half a million deaths in the 20th century, has been completely eradicated. Others, such as tuberculosis and cholera are still with us, but we now understand how to prevent and contain them. Perhaps one day we will wake up to the importance of devoting comparable resources to understanding how to prevent, contain, or even eradicate the plague of dehumanisation.

Such an effort is long overdue.