You know what an HIV criminal looks like. It is Zdeněk Pfeifer, the Czech ‘HIV spreader’ who infected his homosexual partners apparently deliberately. It is Daryll Rowe, the British hairdresser who said he was ‘riddled’ with HIV and infected five men. Rowe also sabotaged condoms during sex with five others, and told one of his victims: ‘I got you. Burn. You have it.’ The HIV criminal is Valentino Talluto, an accountant from Rome who met women online, had sex with them and left them diseased. It is the scheming, feckless tabloid villain with his or her – it’s mostly men, but there is the occasional woman – trail of infected and appalled lovers, reckless with sex, and intent on harming others. These monsters, these deliberate infectors.

In 2006, Leslie Flaggs met a man at her Bible study group. She was a 40-something HIV-positive woman in Sioux City in Iowa; he, it turned out, was an abusive partner who regularly beat her. He told her that if she called the police he would say that she had exposed him to HIV. She didn’t call the police, but neighbours did. Under Iowa’s 709c law, she got a 25-year suspended sentence, four years’ probation, and 10 years on the sex-offender register after her partner claimed she had not disclosed her status. Flaggs, a victim of domestic violence, became an HIV criminal. And in 2009, Nick Rhoades from Iowa was sentenced to 25 years in prison for not disclosing his HIV status to his partner. The same year, Robert Suttle made a plea bargain when he was accused of not disclosing his status by an ex, and served six months in a Louisiana jail.

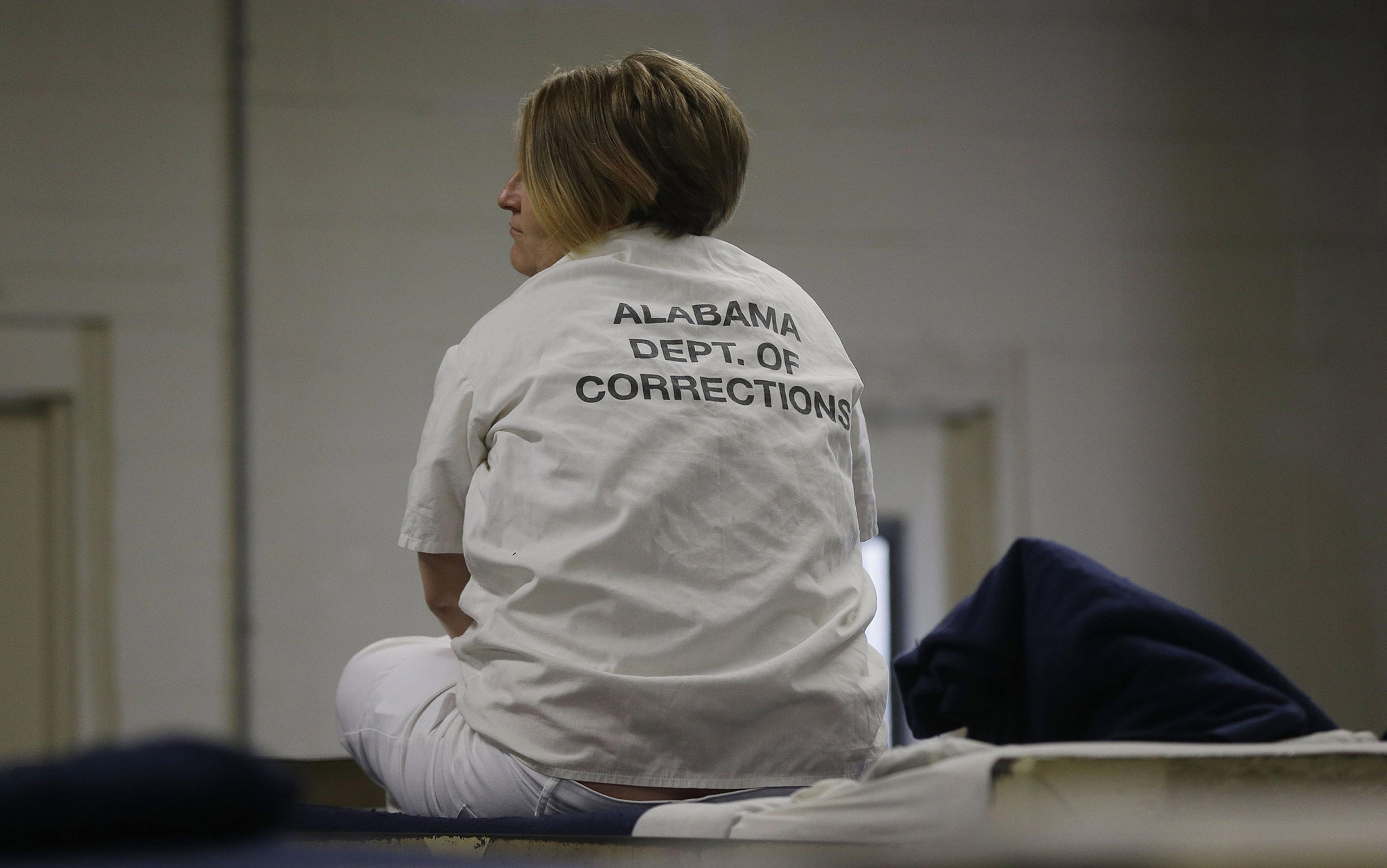

Flaggs, Rhoades and Suttle have something in common besides HIV, or the human immunodeficiency virus: they didn’t infect anyone. Nobody came to harm. But you don’t have to infect someone to be judged an HIV criminal. Between 2013 and 2015, Russia arrested, prosecuted or convicted at least 115 people for HIV crime, a broad category that includes non-disclosure (not telling your sexual partner that you have HIV), exposure (putting someone at risk by sexual or drug activity because you have HIV), or transmission (infecting someone); the United States imprisoned 104; Italy at least six; Australia at least five; Germany the same. Between 2015 and 2017, Belarus prosecuted 128 cases under Article 157, an HIV law considered one of the most draconian in the world, as it prosecutes infection by thoughtlessness or ‘indirect intention’. In Utah, HIV-negative people involved in prostitution or using a prostitute get a misdemeanour sentence of not more than six months; for an HIV-positive transgressor, the offence is a felony with a five-year prison term whether anyone was infected or not.

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) calculated that 46 per cent of the planet now provides antiretroviral medicines (ARVs) free of charge. In those areas, if an HIV-positive person takes the drugs, he or she can be what is now known as undetectable and untransmittable. The medication reduces the level of virus in the body to the point where it cannot be seen by a standard test, and the risk of transmission is thought to be ‘scientifically equivalent to zero’, according to the authors of the huge PARTNER-2 study. However, this spectacular medical advance is irrelevant to the statute books in far too many countries and states. In the US, 11 states criminalise the transmission of HIV by spitting or biting, which is almost impossible to achieve.

In 2018, the science of HIV and the laws devised to limit its spread are jarringly dissonant. Not least, the mere fact of having HIV can still be a criminal offence in countries where living with the virus now mostly means having a normal lifespan and there is no chance of infecting anyone else. What’s going on?

‘Stigma’, from stick and from Greek: the word comes from the practice of marking slaves with a brand or a coloured dot. Stigma creates a boundary and a wall between them and us, though the ‘us’ changes, and so does the ‘them’. Stigma is usually visible but not always: I have met girls and women in Nepal confined to unheated sheds during their periods because of an invisible taboo – as powerful as stigma, but with no branding other than banishment. Taboo, stigma, purity and pollution: they are all management practices to keep the righteous population safe.

Over time, as the American author Susan Sontag wrote in Aids and Its Metaphors (1989), the most terrifying epidemics have been the ones that marked and deformed. They become the plagues: ‘The most feared diseases, those that are not simply fatal but transform the body into something alienating, like leprosy and syphilis and cholera and (in the imagination of many) cancer, are the ones that seem particularly susceptible to promotion to “plague”.’ Logic has little to do with this demarcation: some of the most terrifying diseases are not fatal and are difficult to get. Another ingredient that helps stigma to attach is sex: when human fault can be blamed, how much easier is stigma to justify. Think of the louche syphilitic, the immoral leper (leprosy was thought to be a sexually transmitted disease, though it isn’t). The stigma marks the dirty and polluting; the pure stay safe. Order is kept.

‘There is no such thing as absolute dirt: it exists in the eye of the beholder,’ wrote the British anthropologist Mary Douglas in Purity and Danger (1966). ‘Nor do our ideas about disease account for the range of our behaviour in cleaning or avoiding dirt. Dirt offends against order. Eliminating it is not a negative movement, but a positive effort to organise the environment.’ Purity and taboo, two sides of the same ordering system.

Working-class, an immigrant and an uncooperative woman: Mary Mallon made a perfect scapegoat

HIV/AIDS had all the right ingredients to be a modern plague. Westerners believed that it came from elsewhere (Africa), as did cholera (from Asia) and leprosy (from God), so that foreigners could be blamed. It targeted niche populations – gay men, drug-users, sex-workers – who could be held responsible on account of their dissolution. And it left visible stigmata, with its Kaposi’s sarcoma and wasted bodies. All these things added up to easy scapegoating, and the stigmatising was vile and endemic: the American conservative William Buckley wanted homosexuals to be tattooed. Haemophiliacs infected with HIV by tainted blood products in the 1970s and ’80s in Britain had their houses graffitied with ‘AIDS scum’ and their young sons abused. Baying kept fear at bay.

Mary Mallon was an Irish-born cook in early 20th-century New York who was found to be a healthy carrier of tuberculosis but kept cooking and thus infecting people. She was well-loved in the households where she worked, but once her ‘crimes’ were revealed (she was eventually linked to 51 infections and three deaths) newspapers published cartoons showing her dropping human skulls into a frying pan and called her a ‘walking typhoid fever factory’. Although there were healthy typhoid carriers who caused more deaths than she, only Typhoid Mary got her awful nickname, and only Typhoid Mary was imprisoned for life. Working-class, an immigrant and an uncooperative woman: she made a perfect scapegoat.

Her most famous descendant is ‘Patient Zero’ – a promiscuous Canadian flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas – who was judged to have brought HIV into the ‘civilised’ world. After patient epidemiological investigation, Dugas was absolved, but not in the public consciousness.

And then the virus did an unforgivable thing and spread into the general population. If select groups could not be blamed for the virus, then everyone had to be scared.

Recently, the BBC uploaded a series of vintage public information films (PIFs) that it described as ‘government-approved mini horror movies’. They dated mostly from the 1970s and ’80s, and I remembered them all, because they were all terrifying. Blatant fearmongering, it seems, was a reasonable way to change behaviour 30 years ago, and it worked. The faceless figure with a sinister monk’s hood who is the Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water, waiting for children to fall into reservoirs, pits and ponds. The frying perils of fetching a Frisbee from a pylon. If you were alive then and had a TV, these images would trigger a neural reaction – the one intended – and it was fear. We had so much to be scared of: standing water, stranger danger, electricity pylons, mushroom clouds, not to forget ‘clunking’ and ‘clicking’ (those buzzwords from Jimmy Savile’s 1970s campaigns promoting the use of seatbelts, which featured humanoid dummies plunging through car windscreens). There is, though, a PIF that the BBC didn’t include, and it was the most frightening of all.

Anyone who watched TV in Britain in 1986 will remember the tombstone ad. Disturbing music with spooky clangs. A colour scheme of black and grey and sinister. An exploding volcano, a pummelling rock fall, then a disembodied pair of hands chiselling at a rock, carving the word ‘AIDS’ onto a dark slab. John Hurt narrated, warning in an eerie baritone of a danger that threatened us all. Anyone could get it, man or woman. ‘So far it has been confined to small groups, but it’s spreading.’ A gravestone rises out of dark mist, then falls back with a crash, as we are told not to die of ignorance, before a bouquet of white lilies is flung on the ground, along with a government pamphlet. On YouTube, someone has uploaded the film with the caption: ‘This is the public information film that scared the fuck out of everyone in the 80s.’ The advert was criticised for excessive scaremongering. Actually, the filmmakers had originally wanted to start with nuclear sirens, but the prime minister Margaret Thatcher considered that would be overdramatising matters. As one of the film’s designers Malcolm Gaskin told The Guardian in 2017: ‘If we’d kept it like that I think everyone would have headed for the beaches.’

AIDS has been the bogeyman of my lifetime. I still fear it, because the conditioning worked. But others don’t. Today, the tombstone ad is forgotten, along with the fact that HIV is still a threat, but usually only in poor countries or among high-risk populations (prisoners, stigmatised homosexuals in the Middle East, straight women infected by their partners). Ask any young person in many countries around the world, including mine, whether they worry about AIDS. They do not. Virologists tell me their students think the lectures on HIV are history lessons.

The virus is once again a plague only of niche populations. And with that, the stigma resurges

AIDS professionals now talk of a plateau. Things are better: fewer children are infected, fewer people are dying (just under 2 million per year 10 years ago, and fewer than 1 million per year now). I don’t think it’s a plateau but a fork. HIV still kills, but now it has gone back to killing the other. Worldwide, HIV is now an epidemic of straight women, but these straight women are in the developing world. The young people who think HIV is history will look at the 36.9 million people now living with HIV, and think them all to be elsewhere. Ignorance or ARVs ward off the disease equally as powerfully.

In 2017, the US government changed its website AIDS.gov to HIV.gov, to reflect the fact that, now, so few Americans die from AIDS. (This does not apply to black gay men in the US, who, if current rates continue, will be infected at a rate of one in two.) Formal entry and travel restrictions for people with HIV have been relaxed in most countries, though you will have trouble in Bahrain (which deports anyone testing HIV positive), Iran (where anyone staying longer than three months must be HIV-negative), Iraq (which requires anyone staying longer than 10 days to have an HIV test, and deports anyone who is HIV-positive), and half a dozen others.

The US removed entry restrictions in 2010, 14 years after HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) was developed. Not only can people living with HIV enter the US ‘like anybody else’, according to the Global Database on HIV-specific travel and residence restrictions, but the US visa-waiver programme no longer considers HIV a communicable disease. This is a puzzling decision, since it is not true. HIV is a communicable disease because it depends on humans behaving recklessly: having unprotected sex or taking drugs. Humans have not stopped doing those things, and never will. The rule change issued by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was more accurate in its language. Its guidelines to physicians about what they must test for in immigrants and refugees read that HIV is no longer ‘a communicable disease of public health significance’.

In the 46 per cent of the world blessed with ARVs, the virus can be tamed into undetectability, and an HIV-positive person can have a normal lifespan. The virus is once again seen as a plague only of niche populations: drug-users, homosexuals, the unsafe, the other. Not us. Not normal people. And with that, the stigma resurges. The marks of AIDS are rarely seen now, except in the indigent. And so we lash out at the transgressors who remind us that HIV is still here, by locking them up. The stigma now surfaces not as hateful graffiti but cold (unjust) justice.

The trouble began with Ryan White. In 1990, the US Congress passed an act named after the teenager who was thrown out of school because he had HIV, and who died of AIDS that year. The act, which aimed to allocate funds to low-income people with HIV, at the same time required US states to show that their statutes allowed them to prosecute people who had exposed others to HIV, or who had transmitted the virus. Back then, any exposure to HIV was seen as equivalent to transmission. Now, virologists know that HIV is actually quite hard to get. There are other viruses that are hardier than this fragile one, which travels only in certain bodily fluids, and cannot be transmitted from air or toilet seats or kissing.

But 72 countries worldwide have specific laws regarding HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission, and 61 of those countries have used them. Hundreds of people are in jail not because they have infected anyone, but because of relationship breakdown or grudge or bitterness. Scotland’s laws are used to prosecute people for HIV exposure, as well as for transmission; England and Wales prosecute only for ‘reckless’ transmission. HIV is used as a weapon, but not usually by the people who carry it.

Change a consonant. HPV, the human papilloma virus. It causes nearly all cervical, anal-genital and rectal cancers. In the UK, 3,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer every year. It is the most common cancer for women under 35, and nearly all cervical cancer is caused by HPV. The virus is a sexually transmitted infection, most commonly passed on through vaginal, oral or anal sex. Does it sound familiar? No one in the UK has been prosecuted for passing on HPV, even if nearly 1,000 women a year in the UK die of cervical cancer.

The difference is not the consonant that the acronym carries. The difference is the population that carries the disease. To understand purity rules, wrote Douglas in 1966, you have to note whom they exclude. For purity, substitute ‘health’. These HIV transgressors are polluting the general population. They are the dirt that threatens order, or at least the current embodiment of threatening dirt. To keep our house clean, to keep the dangers out, we need to ward them off. Humans have always done this in the face of the unexplained assailant. HIV is now explained, but it is not solved. In South Africa, where 7 million people still live with HIV despite decades of access to free medication, HIV-positive teenagers sick of taking their meds are coming off them, increasing the virus’s resistance, and they are unable to afford the more expensive second- and third-line ARVs. Experts there truly fear a second wave of the epidemic.

Severe HIV laws are relics, as much as an amulet or voodoo doll

It is not HIV-positive people we should fear, but the power of this virus. A tamed virus is not a beaten one. Instead, we target what we can more easily attack, and the harsh sentencing is a testament to our lingering fears – fears that should have abated after the breakthrough of ARVs. The law is being wielded as punishment for transgression, a penalty for those who remind us that HIV/AIDS is not beaten. Some cultures use amulets, witchdoctors and potions. I watched once, appalled, as a local healer in Nepal slapped a young girl across the face, screaming at the devil in her to leave her body. Her malaria, probably, paid no attention.

Stigma is ancient though not inevitable, and it flows into the forms required to keep current polluters in their place. It is a product of fear, and perhaps we should not expect humans to override it in fearful times. But the things to be scared of include people with an undetectable, untransmittable virus who do no harm. Overly broad and severe HIV laws are relics, as much as an amulet or voodoo doll.

‘This fright,’ wrote the Roman poet Lucretius in On the Nature of Things, ‘this night of the mind must be dispelled not by the rays of the Sun, nor day’s bright spears but by the face of nature and her laws.’

In 2017, California changed its HIV laws for the better, reducing the crime of knowingly exposing someone to HIV to a misdemeanour, and reduced the attached jail sentence from several years to six months. Now, HIV exposure is on a level with deliberate exposure to other communicable diseases. Illinois and Iowa have tempered their punitive statutes. Even Belarus has announced that it will reform its Article 157, and will reopen cases where women have been prosecuted, even though their partners had consented to the possibility of transmission. HIV laws are reckless. But perhaps worse, HIV criminalisation encourages people to stay quiet about their status, and discourages them from getting tested at all: if you don’t know you have it, you can’t be prosecuted for not disclosing it.

I do not suggest that a man who tells his ex-lovers ‘Burn. You have it’ should be exonerated. But I’d like his danger to be proven deliberate. If this can be proven, then let it be prosecuted. Otherwise, outdated criminal laws must catch up with science, and we should protest loudly when they fail, along with the excellent campaigners of Sero Project and the HIV Justice Network. If not, and if we accept the jailing of people with HIV who have infected no one, and probably couldn’t if they tried, then we are no better than that face-slapping healer, our laws no more superior than his superstition.