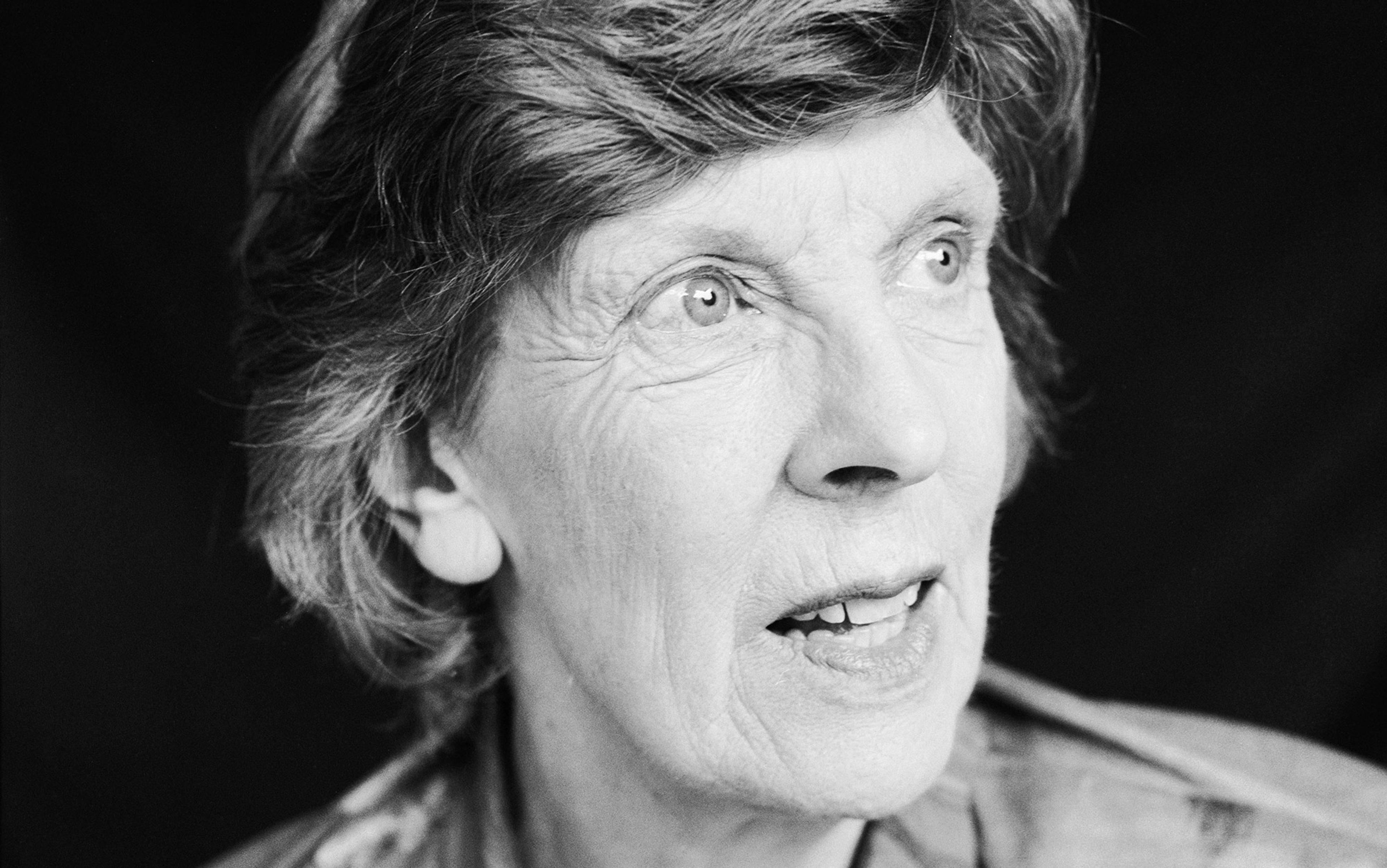

‘I am glad,’ wrote the acclaimed American philosopher Susan Wolf, ‘that neither I nor those about whom I care most’ are ‘moral saints’. This declaration is one of the opening remarks of a landmark essay in which Wolf imagines what it would be like to be morally perfect. If you engage with Wolf’s thought experiment, and the conclusions she draws from it, then you will find that it offers liberation from the trap of moral perfection.

Wolf’s essay ‘Moral Saints’ (1982) imagines two different models of the moral saint, which she labels the Loving Saint and the Rational Saint. The Loving Saint, as described by Wolf, does whatever is morally best in a joyful spirit: such a life is not fun-free, but it is unerringly and unwaveringly focused on morality. We are to think of the Loving Saint as the kind of person who cheerfully sells all of her or his possessions in order to donate the proceeds to famine relief. The Rational Saint is equally devoted to moral causes, but is motivated not by a constantly loving spirit, rather by a sense of duty.

The Loving Saint might be more fun to be around than the Rational Saint, or more maddening, depending on your own personal temperament. Would the constant happiness of the Loving Saint make being with her easier, or would it drive you around the bend? There is an instruction associated with Buddhism – in fact, coined by the American scholar Joseph Campbell – that asks you to ‘participate joyfully in the sorrows of the world’, and the Loving Saint does this to the maximum: but perhaps you would find such joy sustained in the face of the world’s worst horrors inane or inappropriate. On the other hand, the Rational Saint, with his relentless commitment to duty, might be very grating company, too.

Both types of moral saint are likely to present difficulties if you are not a saint yourself. Would they be constantly bothering you and urging you to give more? Perhaps they have joined the effective altruism movement, and are repeatedly suggesting the most effective ways that you can use your time and disposable income to help. How does such a person make you feel when you give much of your spare time and attention not to Oxfam but to video games? And when you give a sizeable chunk of your spare income to luxuries such as wine and chocolate rather than providing others with basic nutrition? Do you want to be friends with someone whose 100 per cent moral focus always seems, in effect, to be encouraging you to feel guilty?

The aspiration to be a moral saint, Wolf suggests, might turn someone into a nightmare to live with and be around. The British writer Nick Hornby offers a comic version of this scenario in his novel How to be Good (2001). But perhaps a true saint, being as decent a person as possible, wouldn’t want you to feel bad all the time: what would be good about that? In fact, wouldn’t true moral saints be as sensitive about their effect on your life as they are about their effect on the world at large? Wolf suggests that the problem then would be that the moral saint would have to hide her true thoughts about your degree of moral commitment. Moreover, can a moral saint laugh sincerely at your cynical jokes when they cut, as Wolf says, against the moral grain? And, in any case, when would they have the time to hang out with you? If they are morally perfect, then they have far more morally important things to be doing.

It’s not only friends that don’t really fit into a life devoted to maximum moral achievement. Can the moral saint, if perfect, ‘waste’ time watching films and television? How about spending any money on fine food or travel? Or expending energy on sport rather than seriously important causes? Or going birdwatching or hiking? No time either for theatre or the pleasures of curling up with a good book. The problem with extreme altruism, as Oscar Wilde is reported to have said about socialism, is that it takes up too many evenings. Moral saints might be able to find time for some of these activities when they happen to coincide with their ethical projects: watching sport, for example, at a charity fundraiser; or admiring the scenery en route to a troubled hotspot in need of aid. But these experiences have to be seen as lucky extras if the only aim in life is to do as much moral good as possible.

If you don’t have enough time for friendship or fun, or works of art or wildlife, then you are missing out on what Wolf calls the non-moral part of life. Wolf does not mean to suggest that non-moral equals immoral: just because something doesn’t have anything to do with morality (playing tennis, for instance) it does not follow that it is therefore morally bad. The point is that morality is, intuitively, focused on issues such as treating others equally, and on trying to relieve suffering. And good things these are: but so is holidaying with a friend, or exploring the Alaskan rain forest, or enjoying a curry. Moral goodness is just one aspect of the good things in life and, if you live as if the moral aspect is the only aspect that matters, then you are likely to be very impoverished in terms of the non-moral goods in your life. And that means missing out on a lot.

Wolf imagines the Loving Saint as perfectly happy to live a life in which non-moral goods play no part. The ultra-ascetic moral life – no friendships, no hobbies, no distractions from the ethical – doesn’t come at a cost for the Loving Saint in terms of contentment. But Wolf wonders how this can be. Does the Loving Saint not see everything that he is missing out on and, if so, how can this not affect his happiness? Perhaps, Wolf suggests, the Loving Saint is almost missing a piece of perceptual equipment: an ability to see that there is more to life than morality. Perhaps this explains why the Loving Saint can stay happy. By contrast, Wolf does not suppose that the Rational Saint fails to see that there is a huge area of life that she is missing out on. Wolf imagines the Rational Saint persisting in her barren life through a sense of duty alone. But why go so far as to live a life entirely and exclusively devoted to moral causes? Wolf suggests answers that makes the Rational Saint look not so rational after all: perhaps self-loathing and/or a pathological fear of damnation.

Wolf’s two versions of moral sainthood are modelled on the two most influential moral philosophies of modern Western philosophy: utilitarianism (which inspires Wolf’s Loving Saint) and Kantianism (which inspires the Rational Saint). What would your life be like, Wolf asks, if you lived these moral worldviews to the max? Wolf suggests that neither worldview, if lived comprehensively, delivers a very appealing life: each, as we have seen, produces a vision of the good life that consists so thoroughly in devotion to the needs of others that there is no time for personal enjoyment of the many non-moral good things in life – no time, in fact, for a life of one’s own. You would spend your whole existence, to echo some words of Bernard Williams, as a servant of the morality system.

Things have gone wrong with modern morality if the expression ‘the good life’ is ambiguous

It is a significant feature of both utilitarianism and Kantianism that neither value personal happiness very highly, if at all. Utilitarianism is a philosophy of ‘the greatest happiness of the greatest number’ and so, if the needs of the many require you to make enormous personal sacrifices, including sacrificing your happiness, then so be it. Wolf rightly imagines the perfect utilitarian, the Loving Saint, as a happy person: and indeed that would be ideal. But no one should become a utilitarian for reasons of their own personal happiness or wellbeing: that isn’t the point of utilitarian morality. Your individual happiness, considered in the context of billions of conscious lives, is just a drop in the ocean. If doing the right thing for the general good – eg, selling your main assets and devoting the proceeds to charitable action – would make you unhappy, then that’s a shame, but your unhappiness doesn’t stop the right thing from being the right thing.

Kantian morality is even less concerned with personal happiness. Kantianism, derived from and named after the 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant, is a philosophy that emphasises our rational responsibility to other rational beings (hence Wolf’s ‘Rational Saint’ label). The reason to do the right thing is because it is your duty to others, not because it will make you happy. If other rational beings need our aid – if they are starving or oppressed, for example – then we owe it to them, just as they would owe it to us if the positions were reversed. Kant did think that being moral made you worthy of happiness but that was all he would allow. One suspects that, had he lived to hear it, Kant would have liked the remark attributed to the 20th-century Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: I don’t know why we are here, but I’m pretty sure that it is not in order to enjoy ourselves.

If modern moral theories, followed as ideals, produce unappealing visions of life, then you might think that something is wrong with the theories themselves. Perhaps what is needed is a more well-rounded conception of the good life. In fact, you might believe it a sign that things have gone badly wrong with regard to modern morality that the expression ‘the good life’ has become ambiguous. The expression is ambiguous because you have to ask: do you mean by ‘the good life’ the morally good life or the most desirable life? The former perhaps conjures up images of tending to the poor, and the latter images of tending to a glass of Champagne. The morally good life has become identified with a life of selfless altruism and the most desirable life with a life of self-focused pleasure-seeking. The good life has therefore become split in two opposing directions, and the resulting huge schism seems a cause for concern.

These reflections, among others, might send one in the direction of Ancient Greek virtue ethics in search of views that predate the schism. Many of the most famous philosophers of the period, Aristotle most notably, held views of ethics that encouraged neither selfishness nor selflessness: the best kind of life would be concerned with others, and involve pleasurable engagement with others’ lives, but it would not require impartial dedication to the needs of strangers. Ethics is more concerned with the question of how to be a good friend than it is the question of how to save the world. And, as with good friendships, ethics is both good for you and good for other people. At the heart of Aristotle’s ethics is the ultimate win-win. The best ethical life simply is the most desirable life, and the fulfilment of our social nature consists in living in mutual happiness with others. Ancient views such as Aristotle’s therefore render the schism between morality and personal happiness inconceivable.

Wolf, in depicting moral sainthood in unappealing terms, could easily be misinterpreted as encouraging a return to views such as Aristotle’s. But a careful reading of ‘Moral Saints’ makes clear that Wolf has no such intention. The fact that modern morality has evolved to include extensive responsibilities towards strangers is not something that Wolf wishes to undo. She is quite content to leave the concept of modern morality as it is: strongly altruistic, impartial and global in its reach. It’s quite right that morality concerns the lives of strangers thousands of miles away and that, as far as morality is concerned, the value of a stranger’s life is equal to that of one of your near and dear.

Wolf sees that, given the terrible state of the world, this leaves so much moral work to be done that it could entirely consume one’s life. One could become, or aim to become, a moral saint. But this is not a reason, for Wolf, to reject modern morality. What she does think it shows is that a line has to be drawn between what is morally required of you and that which is morally praiseworthy but not morally required (what philosophers sometimes term the supererogatory). Morality doesn’t oblige you to become a moral saint. Morality doesn’t require you to have no other interests besides morality. You have a life. Having a life doesn’t mean that you don’t take morality seriously or that you have given up on trying to be a decent person.

It’s a trap to think that choosing not to be a saint automatically means that you have to be a sinner. And this has a moral point: rejecting the idea that you should aim to score 10/10 for morality is no excuse for a low score either. In ‘Moral Saints’, Wolf offers a critique of moral sainthood that is also, once properly understood, a defence of morality. She has developed a compelling case for rejecting a way of life guided solely by moral demands, but this does not mean that she wants to throw the moral baby out with the saintly bathwater.

You can be perfectly wonderful without being perfectly moral

One ongoing theme in Wolf’s philosophy is that it isn’t the wisest idea to look to moral theories in order to find comprehensive ideals of how to live. Moral concepts mark out very important areas of life but don’t tell us everything about life or how to live it. It’s therefore not a criticism of a moral theory that life wouldn’t be very appealing if we transformed the theory in question into our sole answer to life’s questions. That would be to misunderstand the role of a moral theory. Wolf, in putting moral theory in its place, wants to liberate moral philosophy from some of its excessive moralism. We can be inspired in how to live by all sorts of sources: a lover we met online, a neighbour, a character in a TV series, a line of poetry.

Wolf is particularly interested in leaving room for individual interests and passions to shape one’s life, and thinks that meaning in life is unlikely to come from morality as such. In part, this is because meaning often comes from commitment to your loved ones, and on numerous occasions your commitment to family and friends will come ahead of your commitment to doing what would be morally ideal. Take an example from a recent psychological study by researchers at Oxford and Yale: if you are committed to your grandson, then you might give him money to fix his car ahead of helping a charity dedicated to combating malaria, even if doing the latter would do more good. The fact that you are not morally perfect doesn’t make you a bad person. You can be ‘perfectly wonderful’, as Wolf says, ‘without being perfectly moral’.

You might find meaning in life from a specific moral cause – working to prevent homelessness for example – but that’s different from trying to find meaning by doing whatever is morally ideal on every occasion. Indeed, the individual character of your life is given by its concrete combination of relationships, passions and interests. Wolf, against the current of much popular philosophical thought, holds the view that meaning in life depends on spending your life absorbed in activities that are objectively good. ‘Meaning in life arises,’ as Wolf says in a brilliant slogan, ‘when subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness …’ But the objective goods that typically provide meaning are, according to Wolf, the non-moral goods that a moral saint’s life would be so sorely lacking in: loving relationships (including friendships), engagement with the natural world, love of fine art or great sport, and so on.

These non-moral goods will in practice be instantiated (as philosophers say) in an actual life: in my case, a loving relationship is, for example, a 20-year friendship with Chris; an engagement with the natural world is a nightly walk through Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire; a love of fine art is a love of Frida Kahlo’s paintings; a love of great sport is a Saturday afternoon following the football. We each have our own subjective attractions to the good things in life. ‘Time,’ as the poet Nick Laird wrote, ‘is how you spend your love.’

Nature lovers aren’t typically concerned about Nature in the abstract but rather about specific goings-on that they are directly involved with: how will the puffins cope at Bempton Cliffs now that the sand eels have been overfished, and so on. You might, however, start out with a love of the puffins and end up joining a moral cause to save them: perhaps a local environmental movement. And this could be taken as evidence that Wolf’s strong distinction between the moral and the non-moral is, in practice, blurry. Love can take you from a non-moral interest to a moral commitment, and it might be hard to specify where that line is crossed.

You might, for example, work as a benefits officer and come to like a particular resident of your district. Concern for her grows into concern over the policies that are changing her life and her family’s life for the worse. You could come to be rather saint-like in your dedication to getting the policies changed. But, if you have absorbed Wolf’s lessons, you will not throw away your whole life for the sake of the cause. You will continue to make time for friends, for lazy summer nights watching the bees hum in the lavender, and you won’t lose that brilliantly sarcastic sense of humour. You won’t become, in other words, a moral saint.