‘One coward may lose a battle, one battle may lose a war, and one war may lose a country.’ This was Rear-Admiral and Conservative MP Tufton Beamish speaking to the House of Commons in 1930, giving voice to an idea that must be as old as war itself. Caring only for his own safety, blowing cover, attracting fire, the coward can be more dangerous to his own side than a brave enemy. Even when he doesn’t run, the coward can sow panic simply by the way he looks – changing colour, as Homer observed in the Iliad, unable to sit still, his teeth chattering. Cowards are also known for soiling themselves.

No wonder soldiers in the field worry about being cowardly far more than they dream of being heroic; or why cowardice is often counted the most contemptible of vices (not just by soldiers): while heroes achieve fame, cowards are often condemned to something worse than infamy – oblivion. As Dante’s guide Virgil says of the cowardly neutrals who reside in the anteroom of hell: ‘the world will let no report of them endure’. Virgil himself doesn’t want to speak of them. Yet speaking about cowards and cowardice can help us judge and guide human conduct in the face of fear.

‘Fear,’ Beamish went on to say, ‘is perfectly natural. It comes to all people. The man who conquers fear is a hero, but the man who is conquered by fear is a coward, and he deserves all he gets.’ But things are not quite so simple as that: some fears are unconquerable. Aristotle said that only the Celts do not fear an earthquake or flood, and we are right to think them crazy. The coward, he said, is ‘a man who exceeds in fear: he fears the wrong things, in the wrong manner, and so forth, all the way down the list’.

We typically judge someone cowardly when his fear is out of proportion to the danger he faces, when he is defeated by such fear, and in consequence fails to do something he should: his duty. We also typically reserve the cowardly label for men, as Aristotle’s and Beamish’s sexist language suggests. Even today, the term sounds strange when it is applied to women, and seems to need some explanation.

If, as Beamish tells us, a coward deserves all he gets, what exactly does he get? Beamish was speaking against a proposal to end the death penalty for cowardice and desertion. His logic was clear. If a coward can cost a country its existence, the country needs to be willing to deprive the coward of his.

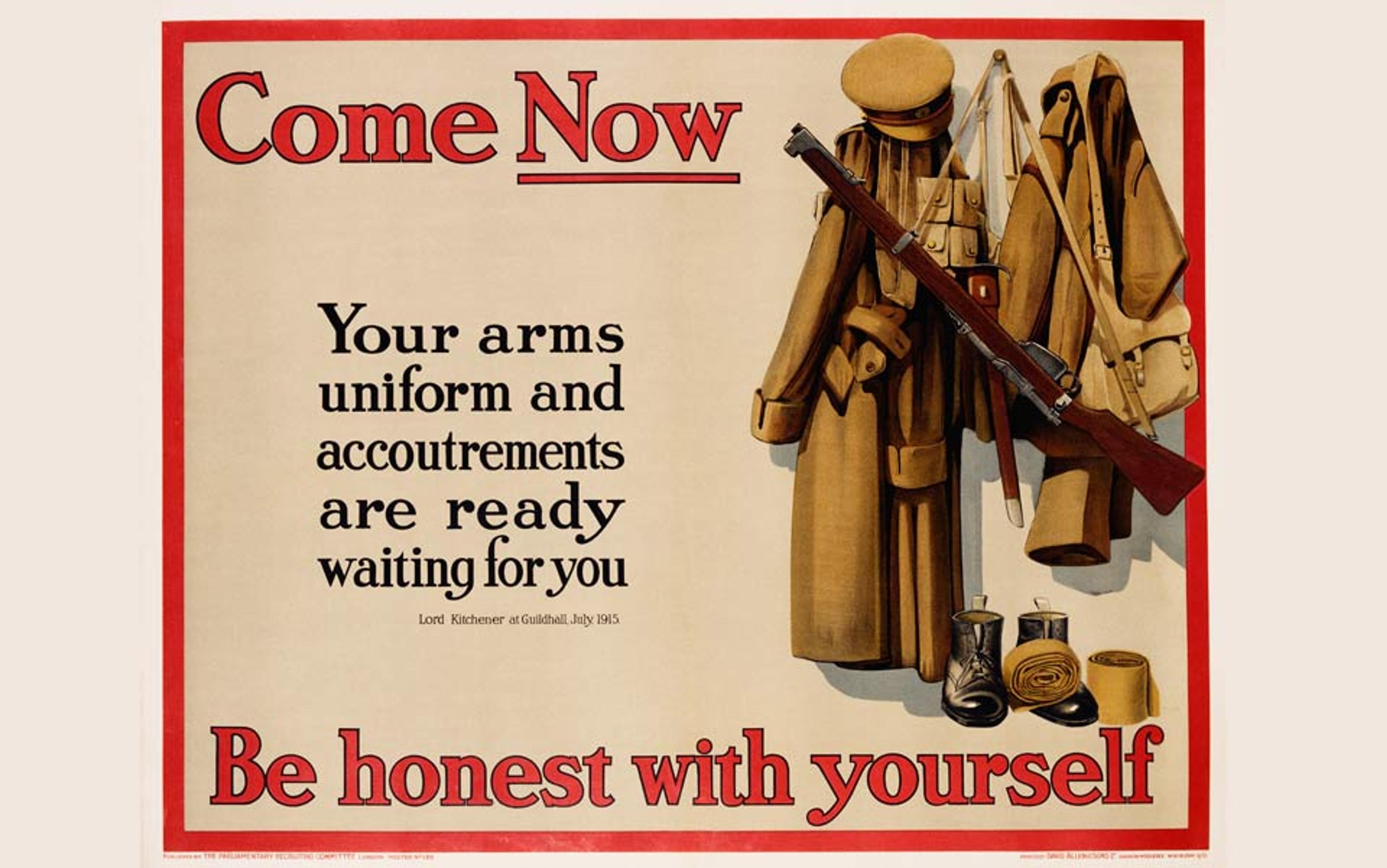

The practice of killing cowards has a long and varied history. The Romans sometimes executed cowards through fustuarium, a dramatic ritual that would begin when the tribune touched the condemned with his cudgel, at which signal all soldiers in the camp would bludgeon the man to death. The preferred modern way is the firing squad. The British and French shot hundreds of soldiers for cowardice and desertion in the First World War; the Germans and Russians, tens of thousands in the Second World War.

Humiliation is a much more usual punishment for cowardice, as Montaigne noted in ‘Of the Punishment of Cowardice’ (1580). Quoting Tertullian’s observation that it is better to make the blood rush to a man’s face than flow from his body, Montaigne explained the thinking: a coward who is allowed to live might be shamed into fighting courageously. The ways of humiliation are even more various than those of killing – from dressing up the coward as a woman, to branding or tattooing him, to shaving his head and making him wear a placard that says ‘coward’, to naming him and recounting his ignominious deeds in his hometown newspaper.

Whether the coward dies or lives, his punishment must be public if it is to fit his crime. In trying to run and hide, the coward threatens the group by setting the worst sort of example and spreading fear like an infection; one coward makes 10, as a German proverb has it. The spectacle of the coward caught and exposed serves as a kind of inoculation for those who witness it, complete with a stinging reminder of the price should they themselves give in to cowardice.

Evolutionary psychologists have had little to say about cowardice, perhaps because it seems such an obvious case of following the evolutionary imperative to preserve the self. But there is widespread agreement that natural selection can favor uncowardly, co‑operative, even altruistic behaviors. Many animals engage in ‘fitness sacrificing’ – advancing another’s chance to live (and reproduce) by risking their own lives. Upon seeing a prowling fox, a rabbit thumps its foot and raises its rear to flash a furry white alarm to its fellows, even though doing so draws dangerous attention to itself. Rabbits that thump increase the survival rate of their relations, which gives the thumper’s genes a better chance of being passed on – if only by way of a sister or brother or cousin – thereby creating more rabbits that thump.

But rabbits do not attack those who fail to thump, and while aggression within species is very common, no animals other than humans are known to punish a conspecific for not performing expected fitness-sacrificing acts. A recent study by Keith Jensen and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in 2012, suggests that even one of our closest relatives, the chimpanzee, does not engage in such ‘third-party’ punishment; it might be a uniquely human practice.

when it comes to war, effectiveness at punishing (and preventing) cowardice improves one’s chances of winning

Third-party punishment of cowardice can happen even without the benefit of an organised military or centralised political system, as Sarah Mathew and Robert Boyd showed in PNAS in 2011. These anthropologists, then at the University of California in Los Angeles, study the Turkana, a ‘pre‑state’ East African people – egalitarian pastoralists who sometimes raid other groups to steal their cattle. If a Turkana man refuses to go on a raid without good reason or flees when danger comes, he can be subject to punishment ranging from ‘informal verbal sanctions’ to severe corporal punishment, including being tied to a tree and whipped. The fact that third parties (and not just kin, neighbours or people endangered by the coward’s actions) participate in the punishment process enables the practice on a large scale, and when it comes to war, all other things being equal, effectiveness at punishing (and preventing) cowardice improves one’s chances of winning.

The Turkana admire and reward bravery in combat, but Mathew and Boyd note that if positive incentives were enough to motivate men to always do the right thing during raids, ‘there would be no need for direct punishment’. They conclude that such punishment does not just enable large-scale co‑operation. It is essential to it. To put it in Beamish’s terms, if one coward can lose a country, and the country is not willing to condemn the coward, then the country itself might be condemned.

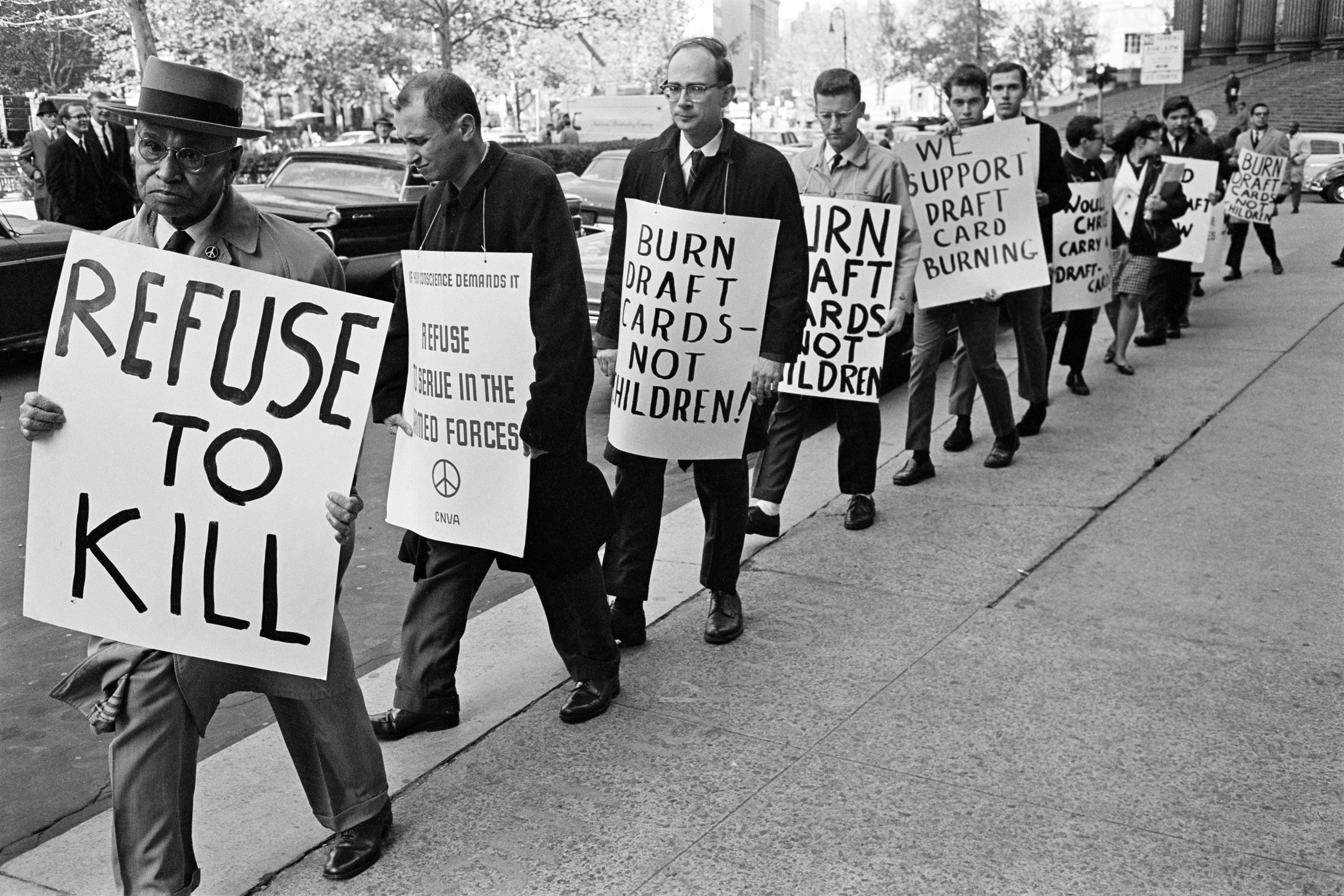

Curiously, though, we have become less willing to condemn or punish cowardice with the passing years. Beamish lost the debate. Parliament abolished the death penalty for cowardice and desertion in April, 1930. Other countries have acted similarly, some in the letter of the law and many more in practice. Under US military code, desertion remains punishable by death during wartime, but since 1865 only one soldier, Private Eddie Slovik, has been executed for it (or any other military crime – rape and murder are a different story), and that was in 1945. Courts-martial for cowardice have become increasingly rare, and many of the European soldiers who were executed for cowardice or desertion in the world wars have been posthumously pardoned. Some countries have monuments honouring them.

There are many reasons for this shift. Foremost is what Ernest Thurtle, the Labour MP who had long campaigned to abolish the death penalty for military crimes, called in the debate with Beamish ‘the almost indescribable strain of modern warfare’. Surely there has always been great strain in warfare, and the military historian Martin van Creveld, for one, doubts that the strain has worsened in modern times, or that suffering through artillery bombardment could be any more traumatic than watching one’s kin get scalped alive. But it’s not unreasonable to think that the scale of modern warfare – its ability to inflict greater damage over greater distance for prolonged periods of time – has produced a greater strain than before. If the Celts did not fear an earthquake, the bombings of Tokyo, Dresden or London might have given them pause.

When it comes to cowardice, whether the strain of modern war is unprecedented is less important than the perception that it is. Shell shock, when that diagnosis was first made in 1915, was thought to be caused by explosives more powerful than the world had ever seen. New weapons must cause new diseases. New terms were needed to explain strange symptoms – tremors, dizziness, disorientation, paralysis – that in women would have been attributed to hysteria. As Elaine Showalter pointed out in The Female Malady (1985), ‘shell shock’ sounded much more masculine.

Seemingly ‘cowardly’ conduct is not a matter of character or manliness but genes, environment, trauma

Even when doctors concluded that shell shock was a purely psychological disorder, the term stuck and became the first of a series of terms (‘war neurosis’, ‘battle fatigue’, ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’) that gave official, alternative ways to, as Thurtle put it, ‘judge the men who had failed with a much deeper sympathy and understanding’. The point is not that soldiers thus diagnosed were actually cowards, but that misconduct that previously would have been considered to reflect a defect in character or a corruption of gender identity was now more likely to be seen as a sign of illness. Monolithic ideas of masculinity were thus complicated and challenged. Moral judgment gave way to medical treatment.

This shift has advanced as medicine has advanced. Thanks to new neurological tests that can detect evidence of blast injuries to the brain that would have gone undetected even a decade and certainly a century ago, researchers have revived the original hypothesis about shell shock – that it had a physical cause. We also know more about how physiological factors such as the formation of the amygdala and cortisol levels make different people constitutionally more or less able to deal with fear. Seemingly ‘cowardly’ conduct (quotation marks rather suddenly become necessary) is not a matter of character or manliness – it’s a matter of genes, environment, trauma. Given this shift, it is not surprising that, according to the Google Ngram corpus, usage of ‘coward’ and ‘cowardice’ declined by half relative to all English words published over the course of the 20th century.

Even as cowardice has lost linguistic currency, however, contempt for it has not disappeared. A century of the therapeutic has not undone millennia of revilement. It shadows even the terms that give us an alternative way of understanding soldiers’ trauma-related derelictions of duty; soldiers are ashamed to seek psychiatric help because it can be seen as cowardly. And one still hears ‘coward’ used pejoratively, as a label for terrorists, paedophiles and other predatory criminals. It’s an unreflective and coarse misapplication of the term, but it shows that the insult endures, even as the idea behind it becomes foggier.

Paedophiles might be cowardly in not confronting their predilections (and their dreadful consequences), and terrorists might indeed be guilty of having what might be called the cowardice of their convictions – an excessive fear of being viewed as cowardly in the eyes of their god, or by the light of their cause. But when we hurl ‘coward’ at such villains it’s usually just a way of expressing contempt for those who take advantage of the vulnerable or helpless. It can feel good, but it can also distract us from pondering our own cowardice and deprive us of an ethical tool that can be useful, and not just to soldiers or men.

‘We all of us suffer from fear,’ Beamish said as he stood before the House of Commons. ‘I am suffering from it at the present moment, but I should be a coward if I sat down and did not say what I feel.’

What he felt was, I think, wrong. To execute someone for cowardice ignores, among other things, what we have learned about human limits in the face of the horrors of modern war. Yet I respect Beamish for not sitting down, and I appreciate how he exploited the shame of cowardice to brace himself for daunting political battle. Though he believed that the man who conquers fear is a hero, I respect Beamish also for the way he does not congratulate himself for heroism. He sets an example worth following the next time you want to speak up for a cause because you think it’s the right thing to do, even if the prospect frightens you. Telling yourself to be a hero might be no more help to you than it is to a soldier. It’s too grand a notion, and the word has been emptied by overuse. (The same might be said of ‘courage’.) But telling yourself it would be cowardly not to stand up and speak might actually get you out of your seat.

‘perhaps we need a coward in the room when we are talking about nuclear war’

The stigma attached to cowardice has caused terrible harm, most obviously to those who have been made to pay for the alleged ‘crime’. Less obvious, but more pervasive, is the damage done by people who, fearing the shame of cowardice, have acted in reckless, often violent ways. Remembering this should make us less ready to use the label of ‘coward’, especially in the case of someone refusing to use violence.

Too often, in retrospect, we realise that a refusal to fight was neither spineless nor craven, but prudent, even courageous. After advising President Kennedy to compromise with the Soviets during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, the US ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson observed that ‘most of the fellows will probably consider me a coward… but perhaps we need a coward in the room when we are talking about nuclear war’. Samuel Johnson noted that ‘mutual cowardice’ keeps us in peace.

Yet the stigma of cowardice can make it a powerful guide and goad for our conduct, and not just in battle or political combat, where Beamish contended, but wherever fear and duty conflict.

We all face similar moral reckonings – instances where the bracing shame of cowardice can be more useful than the exalted dream of heroism – in all sorts of other contexts, including the most personal. And, alas, sometimes it seems as though we all let duty give way to fear, all the time. Mark Twain wrote of ‘man’s commonest weakness, his aversion to being unpleasantly conspicuous, pointed at, shunned, as being on the unpopular side. Its other name is Moral Cowardice, and is the supreme feature of the make-up of 9,999 men in the 10,000’. It is so common, so normal, that it does not feel like cowardice at all.

That might be because the first thing cowardice does, as the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard argued, is to keep ‘a man from knowing what is the good, the truly great and noble, what ought to be the goal of his striving and of his labour early and late’. But thinking about cowardice, pondering the age-old contempt that, for better and worse, still clings to the idea, can concentrate our minds as we work out exactly what we should be doing, and help us confront the fears that keep us from doing it.

In some curious and perhaps contradictory ways, I seek to defend cowardice, first against the coarse and thoughtless application of the term. This has done terrible damage, most obviously to those who have been humiliated or even killed for their alleged cowardice. Even when there might be an element of cowardice in someone’s conduct, we would do well to cultivate a ‘deeper sympathy and understanding’, to use Thurtle’s phrase, in our judgment of them.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline goes further in his novel Journey to the End of the Night (1932) about the First World War and its aftermath. Fearing that he is ‘all alone with two million stark raving heroic madmen, armed to the eyeballs’, his narrator congratulates himself for having ‘sense enough to opt for cowardice once and for all’. Céline presents bravery as the problem, and cowardice as the solution. Stevenson saw things similarly. There are compelling reasons to accept such a position even when we’re not talking about nuclear war; Johnson, after all, noted that ‘mutual cowardice’ keeps us in peace.

But I don’t want to embrace cowardice entirely, and so the second way I want to defend cowardice stands in contrast to the first. The contempt we still typically feel toward cowardice can concentrate our minds as we think about exactly what we should be doing, and about the fears that keep us from doing it. The idea of cowardice can inform our thinking not just in battle or in the obvious combat of politics, where Beamish draws on it. How we love, who and where we are, what we do, what we think, even what we know and allow ourselves to know – sometimes it seems as though these have all been shaped by overblown fears and evasions of duty, held for so long that they feel like normalcy. Pondering cowardice can help us overcome them.

Cowardice: A Brief History (2014) By Chris Walsh is published via Princeton University Press.