The deeply religious 19th-century English naturalist Philip Henry Gosse was not the first person to experiment with fish in receptacles or tanks. Ornamental fishkeeping was an ancient practice. Bowls – first made from porcelain, then glass – had been popular for centuries, but they didn’t have plants to supply oxygen, and no one had yet grasped the complementary respiration of plants and animals.

Jeanne Villepreux-Power had a more direct connection to what later became saltwater aquariums. In the early 1830s, she carried out research on Argonauta argo, also known as the paper nautilus, in Messina, Sicily. She used wooden boxes into which saltwater was pumped via rubber hoses, thus creating a circulation system. She was able to observe that these interesting creatures possessed a lensless eye that functioned much like a pinhole camera.

In 1858, Richard Owen, Director of the British Museum, attributed the invention of the aquarium to Villepreux-Power, even though she seems to have been unaware of the necessity of plants for a functioning system. A few years before Gosse, the Victorian marine zoologist Anna Thynne had brought some stone corals from Torquay to her London apartment, which then bred – to the horror of her housemaids, who had the thankless task of moving the water back and forth at regular intervals by the open window.

But it was Gosse who gave the invention a catchy title, and inspired an extraordinary wave of popular interest for his four-sided glass rectangle. ‘Let the word AQUARIUM,’ he wrote, ‘be the one selected to indicate these interesting collections of aquatic animals and plants, distinguishing it as a freshwater Aquarium, if the contents be fluviatile, or a Marine Aquarium if it be such as I have made the subject of the present volume.’ The enthusiasm he had for his ‘collection’, which he saw as an extension of the countryside, is palpable on every page of his still-captivating book The Aquarium: An Unveiling of the Wonders of the Deep Sea (1854), which includes a beautiful set of colour lithographs.

It triggered a craze for marine aquariums.

And with good reason. At a time when diving was still in its infancy, and rather little was known about the underwater world (the legendary HMS Challenger naval expedition was still two decades away), the aquarium was a revolutionary scientific tool. It granted insights into a strange world that had for centuries been the subject of many wild speculations. Between its panels of glass, the mysteries and conundrums of the ocean were compressed into an easily comprehended menagerie, an oceanic garden in miniature, a submarine chamber of wonders.

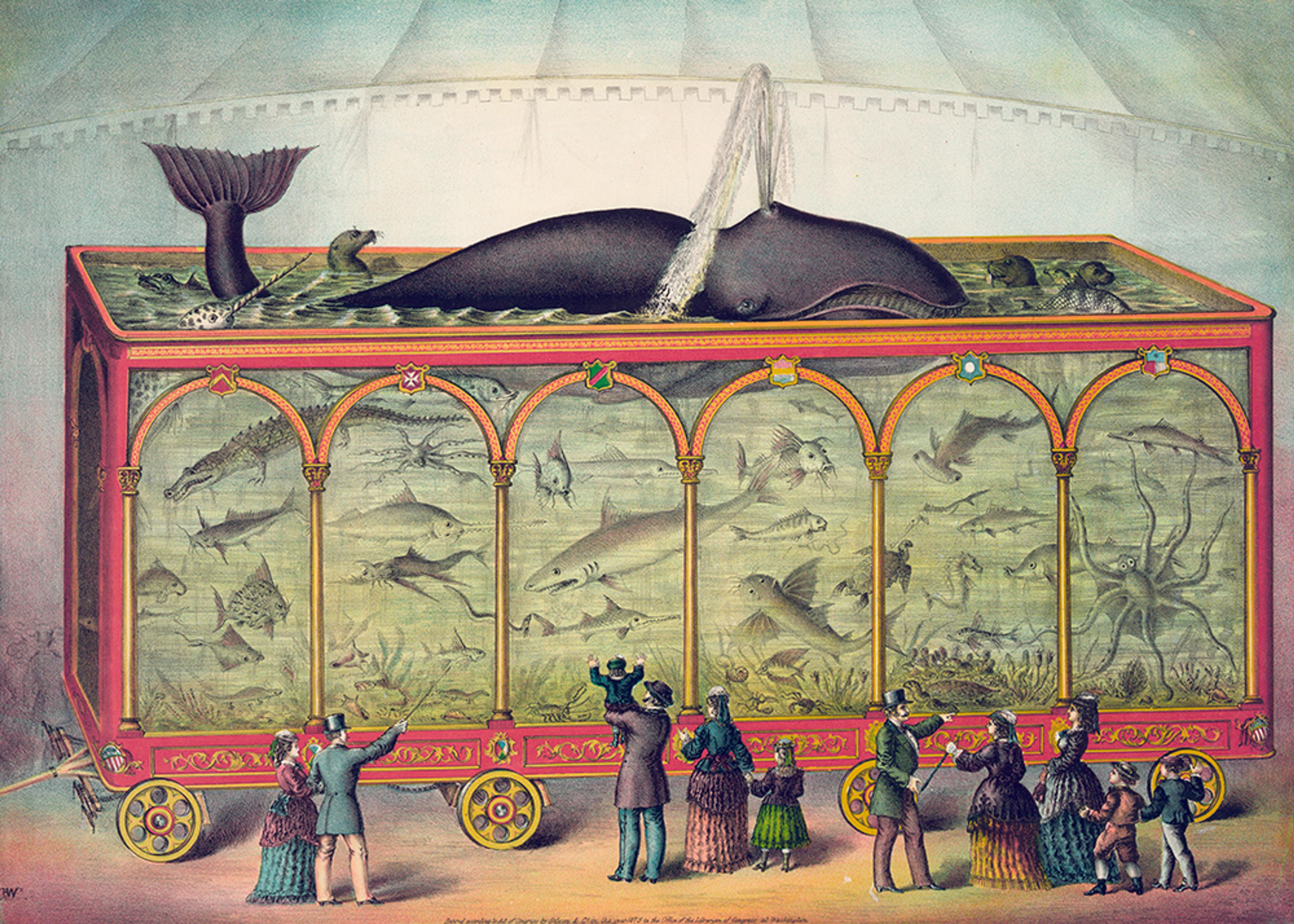

A large travelling circus aquarium filled with sharks, alligators, seals, octopus, narwhal whale and a spouting sperm whale; lithograph, 1873. Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty

Soon, other writers of popular natural history caught on, and the aquarium fever spread. Shirley Hibberd’s Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste (1856) helped, as did many others, including Henry Noel Humphrey’s Ocean Gardens (1857). The fad soon spread to the middle class. Specialist shops started catering to an ever-growing demand for exotic marine pets. Large public aquariums were built, especially in the United States and Germany. Meanwhile, the family aquarium, as the American author Henry D Butler put it in his 1858 book of the same name, had become ‘almost a necessary luxury in every well-appointed household’. It was, Butler wrote, ‘an extraordinary combination of science and art’, an ‘attraction as chaste as it is beautiful, as refined as it is irresistible’.

But even the most chaste and refined pleasures can be taken too far. Half a century later, Gosse’s son Edmund, a poet and writer, wrote in his memoir Father and Son (1907):

The ring of living beauty drawn about our shores was a very thin and fragile one. It had existed all those centuries solely in consequence of the indifference, the blissful ignorance of man. These rock-basins, fringed by corallines, filled with still water almost as pellucid as the upper air itself, thronged with beautiful sensitive forms of life – they exist no longer, they are all profaned, and emptied, and vulgarised. An army of ‘collectors’ has passed over them, and ravaged every corner of them. The fairy paradise has been violated, the exquisite product of centuries of natural selection has been crushed under the rough paw of well-meaning, idle-minded curiosity. That my father, himself so reverent, so conservative, had by the popularity of his books acquired the direct responsibility for a calamity that he had never anticipated, became clear enough to himself before many years had passed, and cost him great chagrin.

During the century that has passed since Edmund Gosse wrote this lament, the aquarium craze has developed into a global business. It is difficult, if not impossible, to get the whole picture. Current estimates say that 25-30 million animals from more than 2,000 species are traded each year. Nearly all the wildlife kept in marine aquariums is captured from coral reefs that evolved over millennia. There are fish imports from the Philippines, Indonesia, the Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Australia, Fiji, the Maldives and Palau. Numbers are difficult if not impossible to obtain, but in both the UK and the US, fish outnumber cats and dogs. (The calculation remains a little skewed, of course, because a single tank often comes with many fish.)

Despite having written about the development of aquariums, I have never owned one myself. In fact, I never found them particularly appealing. Many times I have had to ask myself: why would people want to keep fish in a box? My work on their cultural history was an attempt to understand where the idea had originated and how the keeping of fish had become such a big thing.

Since the publication of my book The Ocean at Home (2005), I have met a great many aquarium aficionados. They are a breed unto themselves, and have developed a whole subculture, with its own magazines, clubs and trade fairs. Some of these people seem responsible and ecologically aware, but many clearly don’t give a fig about how their animals are obtained. And they certainly don’t do the dirty work: their only concern is how to get hold of some species or another. Ever since I started researching these issues, there have been ongoing demands for the origin of animals entering the market to be clearly indicated – but this has yet to be achieved.

The most comprehensive survey of the industry remains ‘From Ocean to Aquarium: The Global Trade in Marine Ornamental Species’ (2003) by the United Nations Environment Programme. I recently got in touch with Colette Wabnitz, who co-authored the study, to ask her how things have changed since. The short answer is: they haven’t. ‘While the key species are pretty much the same,’ she told me, ‘more species overall are being exported, partly as people become more curious and knowledgeable, and partly as aquarium technologies become more advanced.’

Of every 10 fish that are caught for the aquarium trade, only one survives long enough to end up in a hobby tank

Some species are raised in captivity, but they only make up a small part of the trade. Tropical fish and corals present formidable challenges to would-be breeders, because the conditions of a complex coral reef ecosystem can’t easily be re-created. And so, most collectible animals are taken from the wild. Wherever they are harvested, numbers are decimated and the fragile ecological balance is upset or destroyed.

It still seems to be standard practice in many places to use sodium cyanide to numb the fish, making them easier to capture. This is about as good for the environment as it sounds, killing invertebrates and corals, and spoiling their habitat. Anticipating the wastage, collectors usually capture far more animals than would be necessary if they weren’t destroying their very hunting grounds. Underwater nets are a harmless alternative, but fishermen have to be instructed how to use them, meaning that more time and effort is needed.

And what of the catch itself? Of every 10 fish that are caught for the aquarium trade, only one survives long enough to end up in a hobby tank – because of deficient shipping methods, starvation or cumulative stress. These delicate creatures often have very particular requirements. The butterfly fish, with its fascinating variety of colours and patterns, feeds primarily on coral polyps and anemones, and quickly starves to death in captivity. Many saltwater aquarium fish are herbivores that feed on the algae which grows on coral reefs. Raw lettuce and spinach are commonly used as substitutes, but as these are not marine crops they lack the salts and minerals that saltwater fish need.

It is sometimes argued that collecting these animals provides a much-needed income for poor villagers in coastal regions. That’s true enough – to a point. But just like any trade organised on a global scale, there are many other beneficiaries: the wholesalers, middlemen, exporters and importers. The collectors who do the really dangerous work – the ones who are actually handling the chemicals –receive only a pittance. Additionally, the fishermen face the risk of decompression illness or of being exposed to the nerve toxins used to paralyse the fish.

And yet the trade roars on. It’s hard to keep apace with the announcements for oceanariums these days. There always seems to be one in construction that promises the most animals or the biggest tanks or what have you. Is it still the one in Atlanta with its tens of thousands of animals belonging to 500 species? How many sharks do they have? How big are the whales on display? Does it matter? This is a kind of aquatic megalomania. But not even the largest oceanarium could overcome a basic contradiction: it does not recreate ocean wildlife in its natural state. When we see these remarkable creatures through the glass, we see only artifice warped by every possible means to look natural.

It’s true, of course, that contemporary aquariums have little in common with the ones that the venerable naturalist Gosse created. Not only have there been many technical improvements; some even see this hobby as an opportunity to express their creative side by adding objects such as hippos, treasure chests and plastic plants to the tank. Or the tank can be arranged according to a theme or motif, backlit in colourful hues that come into their own at the flick of a switch. Some people even dye living anemones to make them appear more real, as Judith Hamera points out in her illuminating book Parlor Ponds: The Cultural Work of the American Home Aquarium (2012). The aquarium is the ultimate kitsch zone.

These approximations of nature are clearly less than perfect. It’s almost comforting to think that the workings of the ocean are simply too complex, too intelligent, to imitate in a living-room setting. While public aquariums and oceanariums can help to increase awareness of endangered habitats, their raison d’être is mostly entertainment, and the entrance fees contribute to keeping the artifice functioning smoothly. There is no question that people should have the opportunity to appreciate the beauty of reefs. But since the pioneering work of Jacques-Yves Cousteau there has been a much better alternative: film. The makers of underwater documentaries might disturb ocean wildlife to some extent, but at least do not put it at unnecessary risk. And the fish and corals can stay where they belong.

It is a myth that their memories are short; even the humble goldfish has displayed feats of recall spanning months and even years

Aquariums, these personal water worlds, seem to fulfil different functions and fantasies; they might even be able to contain modern anxieties. They certainly help some people to relax. Recent research shows that they can reduce heart rate and blood pressure. During my survey of aquarium owners, I happened to meet a man whose ultimate pleasure was to sit on his sofa, gaze at the colourful miniature world of his saltwater tank, open a bottle of wine and play Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. He wasn’t too forthcoming about the nature of his motivation, but seemed to best fit the category of ‘adventurer/wanderer’.

‘Tinkerers’, on the other hand, focus on the various technical challenges. Others simply enjoy the power and control they have over the miniature artificial marine world in their home. But these are pleasures built on an illusion and at considerable cost. Are saltwater fish really meant to be kept in a glass box, far from home? Isn’t this habit of adorning ourselves with fish – uncomfortably posited in the grey area between animal and toy – nothing more than a failed attempt to heal our psychic and physical breaches with the ocean world?

When I look at an aquarium, I cannot help thinking of the miserable way in which these creatures have journeyed here, and the stupid stage-set they must now call home. Why don’t we just let them enjoy the freedom of their natural environment? It is a myth that their memories are short; even the humble goldfish has displayed feats of recall spanning months and even years. They are intelligent creatures. They surely recognise better than we do the travesty of those miniature sea beds, with their multi-coloured gravel. If we must decorate our homes and our cities in some ghastly undersea theme, at least let’s leave the fish out of it. It’s time to put an end to the cult of the aquarium.