In 1931, a trawler called the Colinda sank its nets into the North Sea, 25 miles off the coast of Norfolk, and dredged up an unlikely artefact — a handworked antler, 21cm long, with a set of barbs running along one side. Archeologists identified it as a prehistoric harpoon and dated it to the Mesolithic age, when sea levels around Britain were more than 100 metres lower than they are today, and the island’s sunken rim, at least according to some, was a fertile plain.

As long ago as the 10th century, astute observers noted that Britain’s coastlines were fringed with trees, visible only at low tide. Traditionally, the ‘drowned forests’ were regarded as evidence of Noah’s flood — relics of an antediluvian world whose destruction is recorded in the most enduring of all the stories of great floods that sweep the earth and drown its people. At the beginning of the 20th century, another explanation was proposed by the geologist Clement Reid. In his book Submerged Forests (1913), Reid argued that ‘nothing but a change in sea level will account’ for the position of trees stretching from the high water mark ‘to the level of the lowest spring tide’. Observations on the east coast of England led him to conclude that the Thames and Humber estuaries were once ‘flanked by a plain, lying some 40-60 feet below the modern marsh surface’.

Turning his attention to a substance known as ‘moorlog’, dredged up from the bed of the North Sea at Dogger Bank, Reid identified nothing less than a time capsule. Moorlog consists of the compacted remains of animal bones, shells, wood, and lumps of peat, and Reid’s sample contained a variety of bones, including bear, wolf, hyena, bison, mammoth, beaver, walrus, elk and deer. He concluded that ‘Noah’s woods’ once stretched far beyond the shore, with Dogger Bank forming the ‘edge of a great alluvial plain, occupying what is now the southern half of the North Sea, and stretching across to Holland and Denmark’.

The Colinda antler appeared to confirm Reid’s theory, for it came from a freshwater deposit, meaning that it had not been dropped by a sea voyager, but by someone living in the landscape. According to Vincent Gaffney, Simon Fitch and David Smith — the trio of archaeologists at the University of Birmingham who have made the most sustained attempts to build on Reid’s research — this was ‘the first real evidence that the North Sea had been part of a great plain inhabited by the last hunter-gatherers in Europe’.

mankind’s wickedness upset the sun-god Nákúset so much that he wept a global deluge

The area, now called Doggerland, was gradually submerged as the last Ice Age came to an end, and the melting glaciers raised sea levels. Only around 5,500 BCE did Britain finally become an island. The rediscovery of the great plain that formerly connected it to mainland Europe is one of the most remarkable scientific stories of the past decade, yet there is a sense in which it should not come as a surprise at all. Doggerland addresses one of our oldest preoccupations; for we have always told stories about lost civilisations, hidden beneath the waves.

Tales of great deluges evolved for obvious reasons: the earliest human civilisations appeared in Mesopotamia (‘the land between the rivers’), and the deltas of the Yellow River, Indus and Nile. The Egyptian year — the basis of our calendar — divided the seasons by the pattern of rainfall, the season of inundation being when the Nile rose, flooding the surrounding fields. Water was the source of life but also destruction and, as such, it inspired the earliest recorded version of the most famous ‘flood myth’ of all. The story of a Utnapishtim, a just man who is instructed by a god to build an ark so as to survive a flood, appeared in The Epic of Gilgamish. In the Bible Utnapishtim is Noah, and in Greek mythology he is Deucalion, a son of Prometheus who recreates the human race by throwing his mother’s bones over his shoulder. There is a Hindu Noah, an Incan Noah, and a Polynesian Noah. A First Nation version of the legend maintains that mankind’s wickedness so upset the sun-god Nákúset that he wept a global deluge.

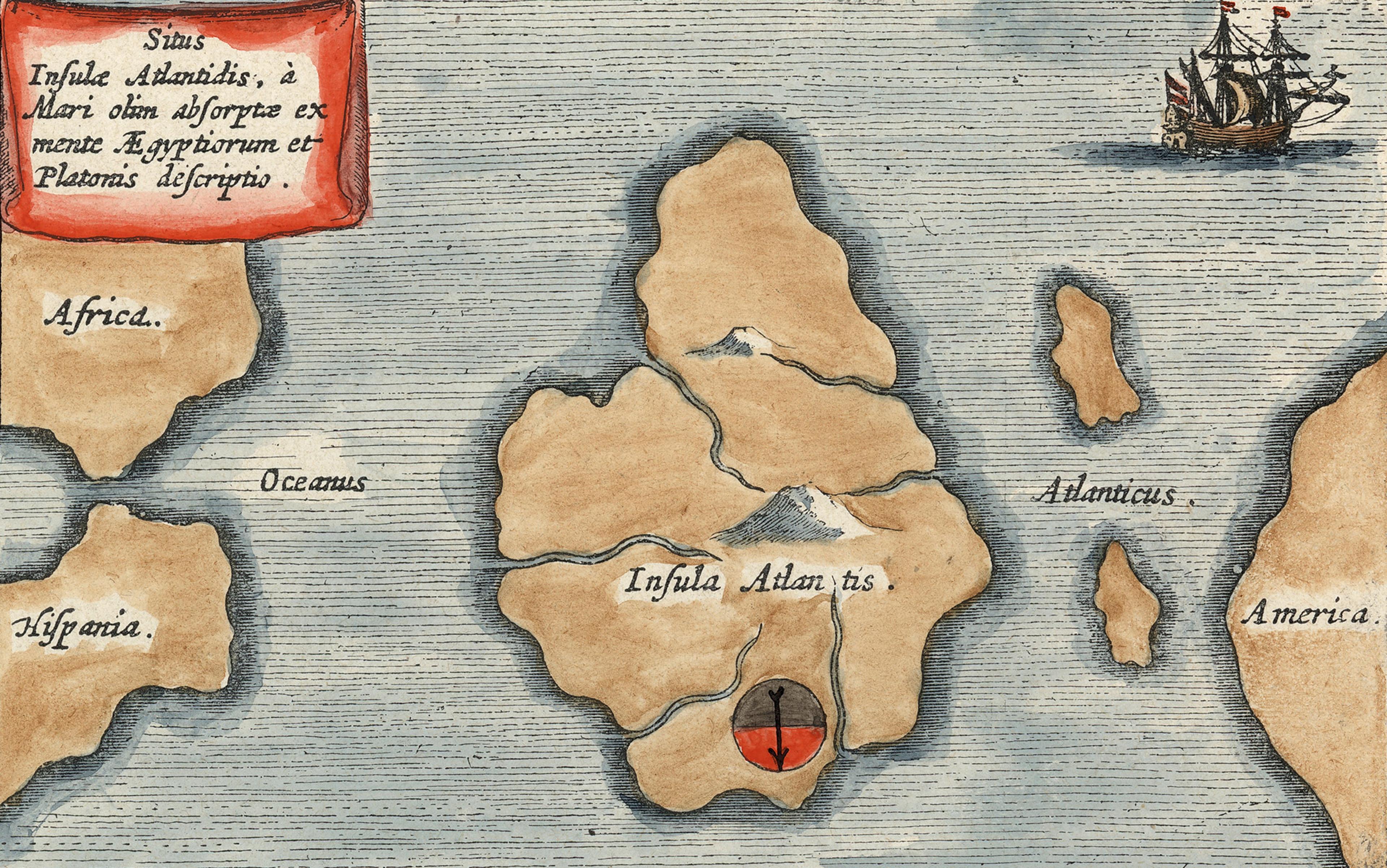

Some creation myths — Genesis, for example — depict God creating land from a primeval waste of water, but another frequently recurring story reverses the process. In Plato’s dialogue Critias we have the oldest surviving account of a land that sinks beneath the waves: the lost continent of Atlantis. In Plato’s original rendering, Athens is said to have ‘checked a great power that arrogantly advanced from its base in the Atlantic Ocean to attack the cities of Europe and Asia’. That power was Atlantis — an empire ruled by descendants of Poseidon, ‘a powerful and remarkable dynasty of kings’. Athens rose up and subdued Atlantis, but her triumph was overtaken by natural disaster: in ‘a single dreadful day and night, all [Athens’s] fighting men were swallowed up by the earth, and the island of Atlantis was similarly swallowed up by the sea and vanished’.

Scholars often insist that we’re not meant to take accounts of Atlantis literally. ‘The idea is that we should use the story to examine our ideas of government and power,’ says the philosopher Julia Annas in Plato: A Very Short Introduction (2003). ‘We have missed the point if instead of thinking about these issues we go off exploring the sea bed.’

The exact location of Atlantis aroused little interest in antiquity, and early modern writers such as Thomas More and Francis Bacon explored Platonic ideals of the good society, in Utopia (1516) and New Atlantis (1624) respectively, without becoming bogged down in questions of geography. Yet recently we have renounced the challenging task of interpreting Plato’s layered inquiry into the nature of the good society in favour of millennial fantasies about drowned worlds.

In the children’s novel The Water-Babies (1863) by Charles Kingsley, Atlantis is merged with the legend of Tír na nÓg or ‘St Brandan’s fairy isle’, a ‘great land’ that sank beneath the waves to the west of Ireland. Kingsley’s story suggests that the surviving traces of Atlantis are not the sunken trees of ‘Noah’s woods’ but the ‘strange flowers, which linger still about this land’, such as ‘the Cornish heath, and Cornish moneywort’. He described the flowers as ‘fairy tokens left for wise men and good children’. Other writers have imagined the survival of more substantial remains of the sunken world.

In Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), Jules Verne describes the occupants of the submarine Nautilus climbing through a sunken forest on the slopes of an erupting volcano on the bottom of the Atlantic until they find themselves looking down on a ruined town — ‘its roofs open to the sky, its temples fallen, its arches dislocated, its columns lying on the ground’. For the benefit of the submariners, Captain Nemo chalks a single word onto a rock of black basalt: ‘ATLANTIS’. Aronnax, the marine-biologist who narrates the book, is transfixed by the thought that he’s standing ‘on the very spot where the contemporaries of the first man had walked’.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle offered another version of the legend, though his Atlantis was not, like Verne’s, a ‘perfect Pompeii escaped beneath the waters’ but a miraculously preserved and inhabited world. The underwater explorers of his short novel The Maracot Deep (1929) are assailed by a giant crustacean that snips the cable of their ‘bathysphere’, plunging it to the bottom of the sea. They are rescued by the surviving Atlantans and taken — as curiosities — to their submarine city.

The occultists were right in one respect: we live on the edge of drowned worlds and are descended from their inhabitants

Conan Doyle threaded his spiritualist beliefs throughout the tale in a way that illustrates how lost worlds might allow us to improve upon the real one, if only in imagination. But the Atlantis myth also allows us to rehearse our fears and fantasies of collapse and decay. In his novel After London (1885), the Victorian naturalist Richard Jefferies portrayed Britain as a kind of Atlantis, its capital reduced to a putrid swamp, its interior covered by an inland sea. Similarly, J G Ballard’s early novel, The Drowned World (1962), pictures futuristic London as a tropical lagoon. Ballard’s characters welcome the re-emergence of a primeval world: we fear the flood, his book implies — and yet embrace it too.

In 1954, the American science fiction writer L Sprague de Camp said that the number of novels and stories about lost continents was ‘beyond count’. Yet the treatment of the subject was not confined to books that advertised themselves as fiction.

The great champion of Atlantis as ‘veritable history’ was an American politician called Ignatius Donnelly, who served as a congressman and state senator for Minnesota at various times in the late 19th century. Donnelly was also a land speculator, farmer and fantasist, who proposed three equally striking and implausible theories — that Bacon had not only written Shakespeare’s plays but embedded a cipher within them; that great events in the Earth’s history, such as the Ice Age, were brought on by ‘extraterrestrial catastrophism’; and that Atlantis was a fragment of a once vast oceanic continent.

In Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882), Donnelly identified Plato’s Atlantis as source of all humanity’s lost paradises: ‘the Garden of Eden; the Gardens of the Hesperides; the Elysian Fields’. It represented ‘a universal memory of a great land, where early mankind dwelt for ages in peace and happiness’. Donnelly believed that a few lucky survivors of Atlantis’s drowning had escaped ‘in ships and on rafts’ to populate surrounding continents, citing, as proof, resemblances between European and American plants and animals, culture and language. Sprague de Camp notes that ‘most of Donnelly’s statements of fact… either were wrong when he made them, or have been disproved by subsequent discoveries’. And even if they hadn’t been wrong, he would still have drawn the wrong conclusions from them: the fact that people on both sides of the Atlantic used spears and sails, customarily married and divorced, and believed in ghosts and flood legends ‘proves nothing about sunken continents’.

Of course, being wrong is rarely a bar to success, especially in the realms of fantasy and conspiracy. Donnelly’s book was reprinted 22 times in the eight years after publication, becoming ‘the New Testament of Atlantism’. And Donnelly attracted a curious following among 19th-century occultists such as Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, who founded the Theosophical Society. Blavatsky believed that Atlantis was one of several lost continents on which humanity had evolved. She claimed that her esoteric magnum opus The Secret Doctrine (1888) was originally dictated on Atlantis, and that part of humanity was descended from another ‘root-race’ who lived on the vanished continent of Lemuria.

Blavatsky did not invent the name ‘Lemuria’: it was proposed in 1864 by the English zoologist Philip Sclater as a way of explaining the presence of Lemur fossils in Madagascar and India, but not in Africa or the Middle-East. Lost land bridges were often invoked to explain how species had travelled across continents separated by water, and Sclater believed that India and Madagascar had been conjoined on a continent that broke apart into islands or sank beneath the waves.

For Blavatsky, Lemuria was ‘the cradle of mankind, of the physical sexual creature who materialised through long aeons out of the ethereal hermaphrodites’. In The Lost Lemuria (1904), her fellow theosophist William Scott-Elliott offered a vivid description of this ‘creature’:

His stature was gigantic, somewhere between 12 and 15 feet… His skin was very dark, being of a yellowish brown colour. He had a long lower jaw, a strangely flattened face, eyes small but piercing and set curiously far apart, so that he could see sideways as well as in front, while the eye at the back of the head… enabled him to see in that direction also.

The theory of continental drift, accepted in the early 20th century, obviated the need to conjure a Lemuria that explained the spread of fossils, but the idea has continued to fascinate occult writers. The American writer Frederick S Oliver pulled Lemuria into an orbit of spiritualist ideas, including spirit guides, astral travel and channelling. His 1905 novel A Dweller on Two Planets (1905), supposedly written under ‘spirit guidance’, tells the story of a community of sages who escaped from Lemuria and settled on Mount Shasta, near Oliver’s home in northern California.

Oliver’s book has been surprisingly influential. The idea of a Lemurian community living on Mount Shasta was frequently reported during the 1920s and ‘30s, and acquired a surprising degree of detail. There were said to be 1,000 magi, living in a ‘mystic village’ built around a Mayan-style temple. Occasionally, they appeared in neighbouring towns, clad in long white robes, ‘polite but taciturn’. They paid for supplies with gold nuggets and, every midnight, they rejoiced in their escape from Lemuria in ceremonies that bathed the mountains in red and green light. Various Californian luminaries, such as the actress Shirley MacLaine — who recalled a past life as an androgynous Lemurian in her memoir I’m Over All That (2012) — and Guy Warren Ballard, founder of the flamboyant religious movement I AM, were both inspired by Oliver’s novel. It still informs the philosophy of a New Age organisation called the Lemurian Fellowship, which maintains that ‘the continents of Atlantis and Mu [often synonymous with Lemuria] did exist, and still do, sunken beneath the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans’.

The British occult writer James Churchward claimed to have learnt about Mu from ancient tablets discovered in temples in India. His book The Lost Continent of Mu: Motherland of Man (1926) was one of the last great manifestations of our preoccupation with lost worlds. It was published just five years before Pilgrim E Lockwood, skipper of the Colina, hauled up his handworked antler. The wild imaginings of the 19th-century cult of Atlantis were starting to be displaced by a picture of a lost world that was scarcely less astonishing, and which had the advantage of being true.

As early as 1936, only a handful of archaeologists went against the grain of thinking that Dogger Bank was a mere ‘land bridge’ to speculate that its ancient plains would have been ‘especially favourable for settlement’. Over the last decade, however, their ideas have gained credence. In 2001, researchers at the University of Birmingham decided to investigate further. Using seismic data collected by Norwegian oil companies, the archeologists Vincent Gaffney, Simon Fitch and David Smith constructed 3D rendering of ‘shallow deposits’ lying only metres beneath the seabed. They revealed the course of a river, large as the Rhine, that once ran across Dogger Bank. The scale of the lost territory has astonished the three researchers. They do not exaggerate when they write in Europe’s Lost World: The Rediscovery of Doggerland (2009) that they’re exploring ‘an entire, preserved, European hunter-gatherer country’ — a lost land that, at its most extensive, was as large as the UK. The team has now mapped the contours of Doggerland and identified 1,600km of river channels and 24 lakes or marshes. The emerging picture is that of ‘a massive plain dominated by water’. To the modern eye, this environment might appear featureless, even unattractive, yet to Mesolithic communities, it offered rich living.

Gaffney, Fitch and Smith understand that, with or without the science, Doggerland remains one of the most ‘enigmatic’ archaeological landscapes in the world, and that our lack of historic knowledge about the people who inhabited it will prove attractive to fantasists and conspiracy theorists alike. Besides, Doggerland is not the only lost continent to be rediscovered. There’s Sundaland, the coastal shelf in the south China Sea, and Beringia, the land bridge that joined Asia to Alaska. Although yet to be explored in any detail, their existence confirms that the occultists were right in one respect, at least: we live on the edge of drowned worlds and are descended from their inhabitants.

Yet one thing has changed: archaeologists now believe that Doggerland’s hunter-gatherers didn’t settle the British Isles until they were forced to abandon their traditional homes on the low-lying plain. Humanity, of course, has always lived with the threat of great floods; but as water levels begin rising once again, we should remind ourselves that our densely inhabited world contains no comparable havens to which we might retreat.