What do the angelic forces of the Heavenly Host have to do with orgasms? The answer, according to the 12th-century philosopher and theologian Maimonides, was simple. Some invisible forces that caused movement could be explained by God working through angels. Quoting a famous rabbi who talked about ‘the angel put in charge of lust’, Maimonides commented that ‘he means to say: the force of orgasm … Thus this force too is called … an angel.’

Before the discovery of gravity, energy or magnetism, it was unclear why the cosmos behaved in the way it did, and angels were one way of accounting for the movement of physical entities. Maimonides argued that the planets, for example, are angelic intelligences because they move in their celestial orbits.

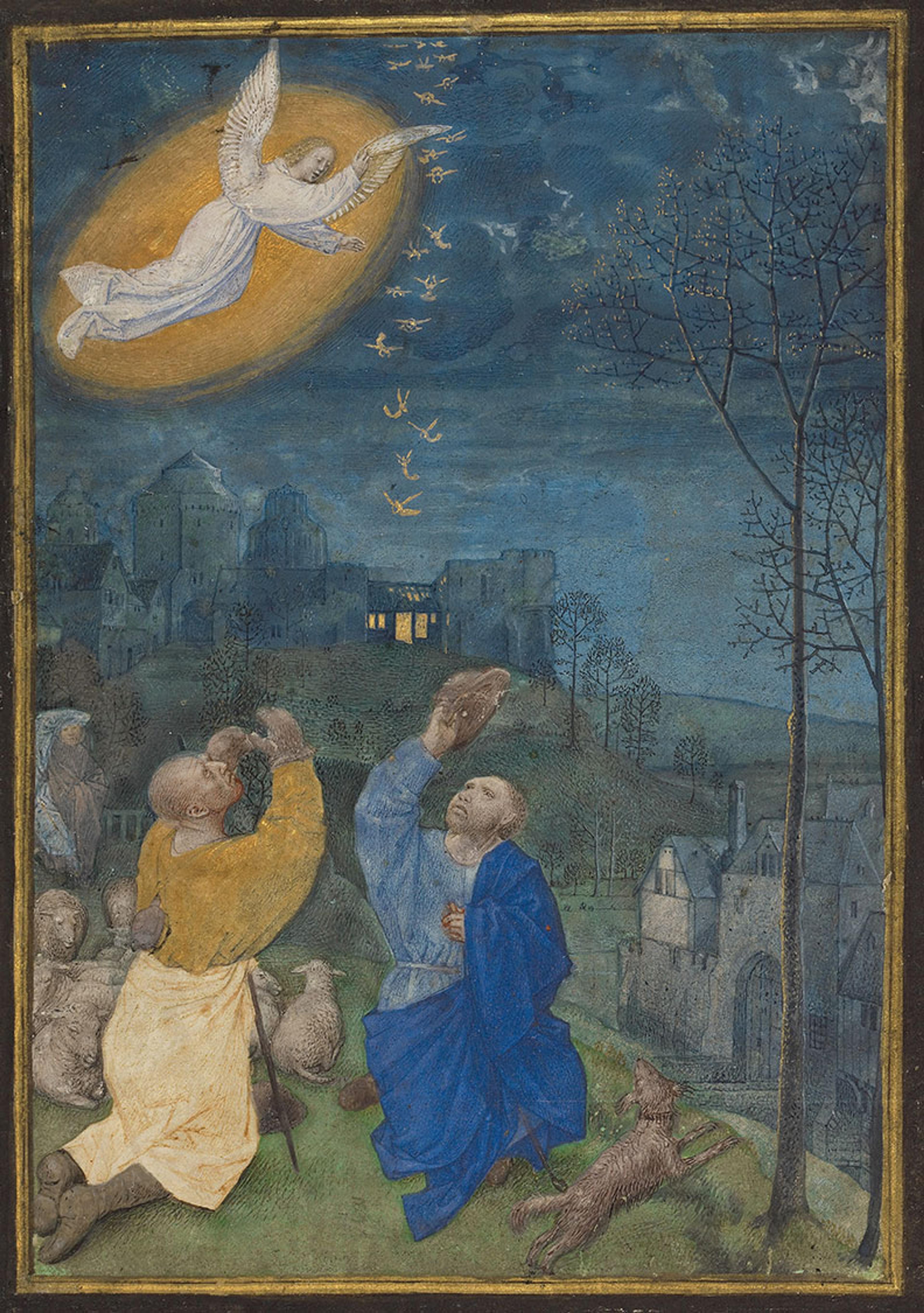

The Annunciation to the Shepherds (c1476-80, Flemish) by the Master of the Houghton Miniatures. Courtesy the Getty Museum, Los Angeles

While most physicists would now baulk at angelic forces as an explanation of any natural phenomena, without the medieval belief in angels, physics today might look very different. Even when belief in angels later dissipated, modern physicists continued to posit incorporeal intelligences to help explain the inexplicable. Malevolent angelic forces (ie, demons) have appeared in compelling thought experiments across the history of physics. These well-known ‘demons of physics’ served as useful placeholders, helping physicists find scientific explanations for only vaguely imagined solutions. You can still find them in textbooks today.

But that’s not the most important legacy of medieval angelology. Angels also catalysed ferociously precise debates about the nature of place, bodies and motion, which would inspire something like a modern conceptual toolbox for physicists, honing concepts such as space and dimension. Angels, in short, underpin our understanding of the cosmos.

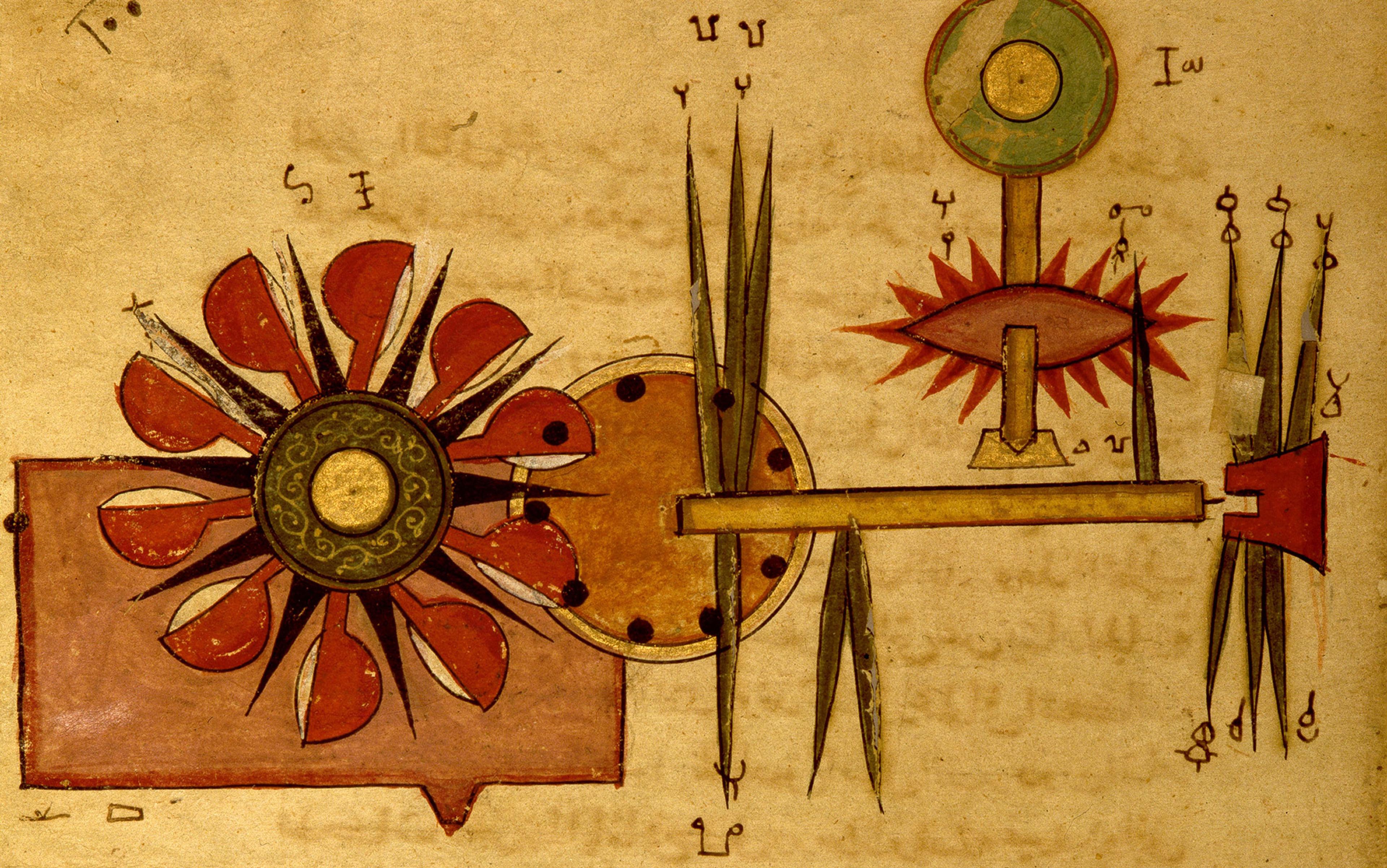

Angels have been around at least since Biblical times, and are described in various, and sometimes odd, ways. In the Book of Ezekiel, for example, the Cherubim have intersecting wheels sparkling like topaz that move them in all four directions without turning, and their ‘entire bodies, including their backs, their hands and their wings, were completely full of eyes, as were their four wheels’. However, aside from these googly-eyed angels, angels were also, as we can see from Maimonides, a way of explaining movement in the world. They were spiritual substances that could take on the appearance of corporeal beings, but also acted as invisible, intelligent, immaterial forces.

This view of angels as immaterial ‘intelligences’ became pretty standard in medieval philosophy and theology. But the scholastic period saw an increasing desire to systematise, systematise, systematise. The precise nature or essence of angels became a serious cause for debate, and these debates were not mere thought experiments. Rather, because of the real belief in the existence of angels, theologians and philosophers could think through angels as a way of understanding the nature of the physical world and things like place, bodies and motion. This was motivated by significant theological concerns. One concern was that, if angels are immaterial intelligences, then what makes them different to God? For us, our bodies are what make us limited, able to exercise force only directly, such as when I throw a ball. Does this mean angels, having no body, could exist everywhere or act at a distance? This was dangerous territory for theologians, potentially challenging God’s omnipresence and omnipotence.

The view was that angels had to be located (ie, limited) but without a body. Angelic location was discussed by prominent theologians such as Peter Lombard, Thomas Aquinas, Peter John Olivi, Giles of Rome, Alexander of Hales, John Duns Scotus, St Bonaventure and many more. It was not a fringe topic, saved for pedants and scholars, but of serious importance in the debates that determined the limits and relations of physics, philosophy and theology. Angelology and its synthesis with the physics of its day would prime later thinkers to reflect on the nature of bodies, place and movement, but also, importantly, how they might relate to each other.

The key to understanding the angelic debates of the scholastic period is to understand what conceptual tools the physics of the day provided. For all intents and purposes, this physics was Aristotle. How the Greek philosopher conceived of place, motion and bodies profoundly shaped the medieval worldview. And some of the most prominent theologians of the day, such as Aquinas, used Aristotle to think about the nature of angelic location.

For Aristotle, physics was simply about things that move and, on his account, bodies don’t move because of gravity or kinetic energy or the warping of spacetime but because of their natures. The nature of fire, for example, is to move up, the nature of earth is to move down. That’s why fire licks the air and a rock falls.

Similarly, there was no concept of absolute space, but rather a concept of ‘place’, which, unlike Newtonian absolute space or Albert Einstein’s spacetime, does not exist entirely independent of the bodies that inhabit it. As the philosopher Tiziana Suárez-Nani points out in Angels, Space and Place (2008), ‘space … as an undifferentiated and homogenous receptacle, was alien to the medieval mind.’ For Aristotle, bodies could not exist without place, which served as a kind of container. Likewise, there had to be bodies for there to be place. In other words, a vacuum is not possible in Aristotle’s view.

In turn, this Aristotelian notion of bodies and place influenced how medieval scholars understood movement. The view was that bodies have a nature that makes them move. This nature makes them move in a certain direction, so place too must be inherently directional. We now understand that direction within space is relative only to a starting reference point; the Universe as we know it has no absolute ‘up’ or ‘down’. But in the Aristotelian worldview, the outermost rim of the celestial spheres provided the absolute reference for ‘up’, with Earth as a stable point at the centre. So, the notion of place had the concepts of either ‘up’, ‘down’, ‘left’ or ‘right’ inbuilt to it. Place was not neutral, but directionally laden, exerting power on bodies because bodies respond to the call of place according to their natures. Fire can travel to an ‘up’ place but not a ‘down’ place etc.

In sum, Aristotle’s physics linked bodies, place and movement, and each depended upon the other.

Aquinas proposed that an angel has a different type of location than a bodily being

So, what has that got to do with angels? If you recall, theological concerns at the time required angels to have a specific location – to be limited and bodiless – in order to avoid angels with limitless power, rendering them omnipotent as well as omnipresent. Since Aristotle’s physics was the reigning physics of the day, medieval scholars worked to explain these location problems within his framework.

Normally, the material body of something locates it, so how can immaterial angels be located? Aquinas and others solved this problem creatively, locating angels not by their physical dimensionality but by their operations. Aquinas proposed that an angel has a different type of location than a bodily being. An angel is in a place by virtue of applying its power to the physical objects in a given place. This limited both an angel’s operations and their location, locating them by their operations, rather than by a body.

But Aristotle’s physics caused quite a few concerns for some 13th-century church leaders. If a body cannot exist without place, this limits God’s power. If God wanted, some claimed, God could create a rock that did not exist in a place, but Aristotle’s view of place and bodies meant that this was not possible. So when the nature of angels became a kind of playground for thinking about the nature of the world, it was an especially fraught subject.

The question of angels came to a surprisingly acute head when the bishop of Paris Stephen Tempier published his Condemnations of 1277, a list of 219 theses that Catholics were prohibited to hold or teach in the university. This was part of a broader rejection of Aristotle and other ‘pagan’ philosophers. These theses covered various philosophical and theological positions, but an impressive 28 of the 219 had to do with angels also known as ‘separate substances’ or ‘intelligences’. Some of these had to do with the nature of angel location and operation. Importantly, the Condemnations of 1277 forbade believing that angels are located by their operations rather than by their substance, so Aquinas’ solution for angelic location was now off the table. If an angel exists in a place solely by its operations, as Aquinas claimed, then what happens when it’s not operating? Angels had to be rethought. What was their nature and essence such that they could be both immaterial and located? This constraint would require even more creative manoeuvring from scholars.

The most notable manoeuvring would come from Duns Scotus. His angelology would redefine the concept of place that was so central to Aristotelian and medieval physics and, as Helen Lang notes in Aristotle’s Physics and its Medieval Varieties (1992), this would shift the contours of physics forever.

Portrait of John Duns Scotus (c1476-8) by Justus van Gent. Courtesy Wikimedia

As we have seen, angels needed to be ‘located’ and operate in a limited capacity, otherwise they would be omnipresent and omnipotent like God. But the Condemnations of 1277 explicitly forbade Aquinas’ explanation: that angels are in a place according to their operations. The challenge for medieval thinkers was to find a way of locating an angel by its essence, without it being a bodily substance, and to locate their operations, but without those operations being the sole factor ‘locating’ the angels.

One innovation that Scotus brought to escape this double constraint is that he redefined ‘place’. He did this to solve the theological problem of God being able to create a rock outside of place, something theologians claimed God could do, but his solution applied equally to angelic location. In doing so, his creative rethinking of physics would lead to new concepts and reconceptualise old ones, shaping modern physics in a quite radical way.

Here’s what Scotus did: he made ‘place’ more mathematical, less tied to location and more similar to our notion of dimension. When thought about in terms of dimension, the ‘place’ occupied by an object stays the same as the object moves through locations. In this sense, its ‘place’, redefined as dimension, is the same, even though it changes location. In other words, Scotus, as aptly stated by Lang, ‘neutralises’ place radically. On the Aristotelian account, direction or location were part of the definition of ‘place’. When redefined more mathematically as a kind of dimension, direction is no longer a necessary feature of this new kind of ‘place’. You can have an idea much more like that of ‘space’, something that doesn’t inherently contain ‘up’, ‘down’, ‘left’ or ‘right’ in its definition.

Angels, because they have no dimensions, can exist only in a determined place in an undetermined way

Technically, this meant that God could create a rock in no ‘place’, if place referred to Aristotle’s definition of place, which was a location within the outermost rim of the heavenly spheres. Whereas Aristotle had defined place as a necessary defining feature of physical bodies, Scotus did not. Instead, he created a hybrid account in which something can exist inside the outermost rim of the celestial sphere (occupying place in the Aristotelian sense), but it doesn’t have to; it could equally just occupy space by having dimension outside of that sphere.

Two Angels (c1330), Italy

Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

So here you have the creation of new concepts, a kind of precursor to dimension and space, and the rejigging of old ones, separating ‘place’ from a necessary relation to bodies. For Scotus, Aristotle’s place could exist, but it didn’t define bodies. If something did exist in Aristotelian ‘place’, it was by God’s will, and because of what Scotus calls a passive power, which simply means that it is able to exist in a place without it going against the object’s nature.

This new physics left the door open for angels. Scotus argues that angels too possess the passive power to exist in a place by God’s will, because in this new physics, place and body are no longer mutually defining. But unlike physical bodies, which must exist in a determined way in a determined place, angels, because they have no dimensions, can exist only in a determined place in an undetermined way. The image Lang uses, citing Scotus, is of a surface that must have colour, but whose colour can be anything. Angels can occupy a place however small or large, just not infinitely so, and they must operate in a place, though they themselves exist in the place indeterminately.

This radical rethinking of Aristotelian physics, catalysed by medieval debates in angelology, allowed a new understanding of the relationship between bodies, place and motion that helped reformulate our understanding of the very fabric of the cosmos. For Aristotle, motion was just inherent to bodies because bodies had natures that made them seek their natural place. To posit angels as immaterial external forces was indeed oddly closer to a classical physics that sees an invisible force like gravity working on bodies externally. In fact, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz accused Newton of having introduced occult forces with his theory of gravity, because gravity seemed to be a supernatural force acting on bodies at a distance.

Thought experiments using angels and demons did not disappear in the modern period, but they did shape-shift. Occult beings, often referred to now as ‘demons’, continued to play a significant role in the development of physics. (Theologically, there is very little difference between demons and angels in terms of their metaphysical make-up. Demons are a subset of angels; they are fallen angels.)

In the 1800s, Pierre-Simon Laplace’s demon (which he himself calls merely an intelligence, a word often used to describe angelic substances in the medieval period) was a being endowed with supernatural abilities to know all of the forces in the Universe and the placement of every atom. This being, in addition, has infinite computational power, which it can apply to calculate the trajectory of each atom. Laplace believed this would yield infinite predictive power, and this superintelligence could therefore know the entire history of the world and the ultimate future of the Universe. Such determinism would later be called into question by quantum mechanics.

In a thought experiment to test the second law of thermodynamics in 1867, the Victorian physicist James Clerk Maxwell imagined a hypothetical being (an ‘agent’) with the supernatural ability to detect the location of the molecules. His contemporary William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) would label it a demon, and the name stuck. ‘Maxwell’s demon’, still called so today, revealed deep connections between information and entropy, evolving our empirical understanding of the world.

Finally, at the turn of the 19th century, the Filon-Pearson demon – proposed by Louis Filon and Karl Pearson – became a so-called ‘colleague of Maxwell’s demon’. It could travel at impossible speeds, teleport, and act at a distance.

Enquiring individuals thought through angels to understand the physical world and the cosmos

Reactions against such uses of supernatural explanation in physics, even as thought experiments, also helped physics evolve. Einstein, for example, will have read Pearson, and his antipathy towards using supernatural explanations meant that he defined his work in a negative relationship to occult forces. The astronomer Arthur Eddington claimed that Einstein banished the demon of gravitation. And Einstein himself claims to have banished the ‘ghosts’ of absolute time and space with his theory of relativity.

But could Einstein have achieved what he did without the precursory belief in angels? Theology certainly motivated a search for alternative accounts relating place, movement and bodies. But although the nature of angels as a topic of focus was the catalyst for discussions about the physics of place, enquiring individuals also thought through angels to understand the nature of the physical world and its relationship to the broader cosmos. And this yielded more complex notions of space, location and dimension, giving them new meaning. The role angels played in such thought experiments was unique: angels transcended the purely physical world but were still ‘creatures’ that abided by the rules and the logic governing the Universe.

In fact, this mediatory role was part of the logic of positing angels in the first place. Angels do feature in the Bible, but Aquinas believed that a priori arguments could be made for angels precisely because the great chain of being couldn’t miss any links. Any gaps mean that human beings could not possibly make the jump to understanding God. We need some intermediary knowledge that would bridge knowledge of God and knowledge of the world. This is why angels, as early as Pseudo-Dionysius in the 5-6th century CE, were equated with language. Speech also mediates between the realm of ideas and the physical world. Otherwise, all the work of angels could simply be explained by God. However, angels, precisely because of their intermediary status, allowed human beings to think about dimensions of created reality that yet transcended our direct human perceptions.

While it is easy enough to ridicule the suggestion that movement is the result of occult forces such as angels, we cannot, having ascended the ladder of knowledge, so easily kick that ladder out from under ourselves. Studies in embodied cognition are showing that our knowledge is built upon our experience of the world. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (1980) shows how our bodily experiences come together to create complex metaphors, grounding abstract concepts. We equate ‘up’ with ‘more’ when we say ‘the stock market rises’ because when we see, for example, rocks piled up, we learn to equate higher with more. We say we ‘grasp’ an idea because we have experienced reaching for a piece of fruit on a tree. In addition, we have a very hard time imagining a nonphysical thing. What we imagine, when we imagine a soul or an angel or a demon, is some kind of insubstantial, but still ghostly, object.

Although occult forces such as angels and demons may be ridiculed in modern culture as ‘hand-wavey’ explanations of quite logical, down-to-earth scientific phenomena, I would suggest the inverse. That what is most down-to-earth might in fact be to think about the invisible forces of nature as angels, agents, immaterial intelligences with certain properties familiar to us, but amplified. Properties like agency and intention. It is only in thinking through, and with, these more familiar concepts that we can then discover a less intuitive set of concepts, like spacetime, which require grounding in concepts like dimension, body, place and movement. These necessary grounding concepts were sharpened, historically, by thinking through the relationship between the material and immaterial world, and angelology played a significant role in their honing.

The use of supernatural intelligences such as angels and demons to think through physics stuck around long after the actual belief in the existence of these beings had dissipated. It seems that this imaginative framework resounds in the actual structure of how our thought operates. By virtue of this, angelology lay the groundwork for thinking through the nature of place, time and motion in quite complex ways. Did angels and demons carve a conceptual space for the invisible forces that physics would later come to discover? Though it may seem that the scientific and the demonic are at polar ends of the spectrum when it comes to explaining the natural world, angels and demons have actually shaped modern scientific explanation as we know it today.