Since September 2019, medieval scholars have heatedly debated the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’. The dispute began in relation to claims of racism and sexism within the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists, which is an academic organisation dedicated to the study of the history, archaeology, literature, language, religion, society and numismatics of the early medieval period (c450-1100 CE). Some scholars argued that changing the society’s name would be a step against racism and sexism, specifically in how academics research and interpret the early medieval past. Rapidly, the criticism moved from striking the term ‘Anglo-Saxonist’ from the name of the society (now the International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England), to arguing that we should stop using ‘Anglo-Saxon England’ for lowland Britain in the mid- to late-1st millennium CE and ‘Anglo-Saxon world’ for the region’s connections across early medieval Europe and beyond.

The campaign quickly degenerated to slurring anyone who disagreed with these changes as ‘racist’, and anyone making a qualifying statement, or correcting or disputing the bases and framing of the debate, as an apologist to the racist uses of the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’. Online proclamations declared that scholars must signal their commitment to change by removing the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ from their writings and courses, as well as to ‘cancel’ those scholars who might wish to persist in using the term.

As an archaeologist of early medieval Britain and Scandinavia, my view is that the term still has a place in both research on material culture, the built environment and landscapes of the early medieval period, as well as its public engagement and education. Those proclaiming that ‘early medieval England’ and ‘early English’ are somehow clearer and less fraught are ill-informed about the contemporary uses and abuses of the early medieval past.

To be clear, there is no question that the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ has appealed to racist and white supremacist political movements, particularly in North America. However, I think that the term’s continuance and coherence in scholarly discourse and public engagement and education is the best way to guard against its misappropriation and abuse by racists and supremacists.

The energy behind the recent controversy stems, in part, from the chequered past of the terms ‘Anglo-Saxon(s)’ and ‘Anglo-Saxon England’. Like ‘Vikings’ and ‘Celts’, these words have long attracted individuals and groups with racist ideologies, especially those focused on national origin myths. In these misrepresentations of the past, Britain was populated by Germanic migrants in the 5th century CE who replaced the native inhabitants. They were freedom-loving farmers and warriors, first pagan and then Christian, defending ancient liberties and fighting off the bloodthirsty Vikings, finally succumbing to the ‘Norman yoke’. Nationalists and racists have appealed to this tenacious romantic little England to try to justify English and British nationalisms and overseas colonial and imperial missions. In the United States, ‘Anglo-Saxonist’ is a favoured piece of jargon of white supremacists. For these British and American nationalists, imperialists and white supremacists, ‘Anglo-Saxon’ stands for a ‘Golden Age’: the kernel of what makes England (and thus Britain) superior.

The growing alt-Right populism, ethnonationalism and white supremacism of recent years have embraced the early Middle Ages as a political symbol. As a result, scholars of the early medieval world have found themselves watching the literature, art and archaeology they study invoked by xenophobic and chauvinistic political groups. At the same time, popular and commercial DNA testing, and hit television programmes, have been perpetuating pseudoscientific stereotypes about the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings.

Like all scientific and humanistic disciplines, archaeology is saddled with an imperialist and colonialist past

In response, some scholars have called out the dangerous trend to claim that all uses of ethnic terms, including ‘Anglo-Saxon’, promote racist myths about the past and exclude publics and practitioners of non-European and non-white backgrounds. Yet in November 2019, pressured by a group of concerned scholars, the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists voted to change its name to the International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England. They saw the change as a response to mitigate or counter the perceived whiteness, sexism and elitism of Anglo-Saxon studies. Some university courses, book titles, scholarly journals and conferences have followed and removed the term from use.

Despite warnings, scholars of literature and language pursued this name-change without regard for archaeological research and public engagement. Like all scientific and humanistic disciplines, archaeology is saddled with an imperialist and colonialist past. Moreover, it is in long-term conflict with persistent ‘fake’ narratives with racist underpinnings, from ancient aliens to national-origin myths. Yet archaeology is also very popular worldwide and for all generations, linked to concepts of adventure, discovery and detection. For many people, ‘Anglo-Saxon’ sites, monuments and material culture are a readymade gateway, particularly in the UK, into the rich and complex stories of the early medieval past.

Therefore, while my scholarship has been devoted to evaluating and critiquing both the history of early medieval archaeology and reinterpretations of the burial archaeology of the period that challenge simplistic ethnic narratives, I came out in favour of retaining critical and cautious uses of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ as a means of countering ethnonationalist and white supremacist appropriations.

When researchers and educators today talk about the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ and ‘Anglo-Saxon England’, they aren’t discussing a ‘racial’ group. The terms don’t even encapsulate one thing, but rather seven centuries of change and very different kingdoms and communities, from Kent to Cumbria, from East Anglia to the Welsh borders. Following the collapse of Roman authority and administration in Britannia in the early 5th century CE, a disparate range of barbarian groups came from across the North Sea from regions as far-flung as modern Norway and the northern Netherlands to inhabit lowland Britain – later remembered as ‘Angles, Saxons and Jutes’ by the Venerable Bede writing in the early 8th century.

Migration was likely a multigenerational process, one of ethnogenesis not ethnic replacement. The political and socioeconomic situation was fluid and unstable, and the Romano-British population remained too. The descendants of the Cantiaci, Iceni, Trinovantes and the other peoples of Roman Britain integrated with Germanic-speaking incomers on different tempos and in varying circumstances. The ‘Anglo-Saxon kingdoms’ emerging in the late-6th century and converting to Christianity at different points during the 7th century shared many complex connections with the British kingdoms also developing to their north and west. There were seven in the 7th century – Kent, Sussex, Essex, Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria – with four surviving in the early 9th century: Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria.

However, in the 9th century, Viking invasions destroyed all but one of these kingdoms: Wessex. The West Saxon kingdom went on to form the foundations of a united England during the 10th century. Ruled by Danish kings for much of the early 11th century, ‘Anglo-Saxon England’ came to an abrupt end with the Norman invasion of 1066. ‘Anglo-Saxon’ is a useful shorthand for complex social, economic, religious, linguistic and cultural processes from the Roman collapse to Norman invasion. Like all names for eras, it is an interpretive device, a tool, helpful in defining the early medieval period from times before and after, but inevitably with many limitations in describing heterogeneous landscapes and societies.

The first known use of the term Anglo-Saxon was in 8th-century Italy where we find it used in Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards. It persisted intermittently in contemporary sources from the reign of Alfred the Great (who died in 899) to Edward the Confessor (who died in 1066), used to describe those kingships and kingdoms.

It was not until the late-18th and 19th centuries that the description ‘Anglo-Saxon’ took off again. Historians and literature and language scholars began using it to refer to Old English-speaking peoples, their kingdoms and connections in the island of Britain. They used it to differentiate the ‘English’ from the Celtic-speaking peoples of the island of Britain, from Norse-speaking ‘Viking’ settlers, and from the Norman kingdom that succeeded it. The ‘Anglo-Saxons’ were thus resurrected as part of a national-origin myth for England in the early Victorian era, and archaeology was a key part of this political programme.

Spurious modern racial categorisations are inexplicable and inapplicable for the early medieval period

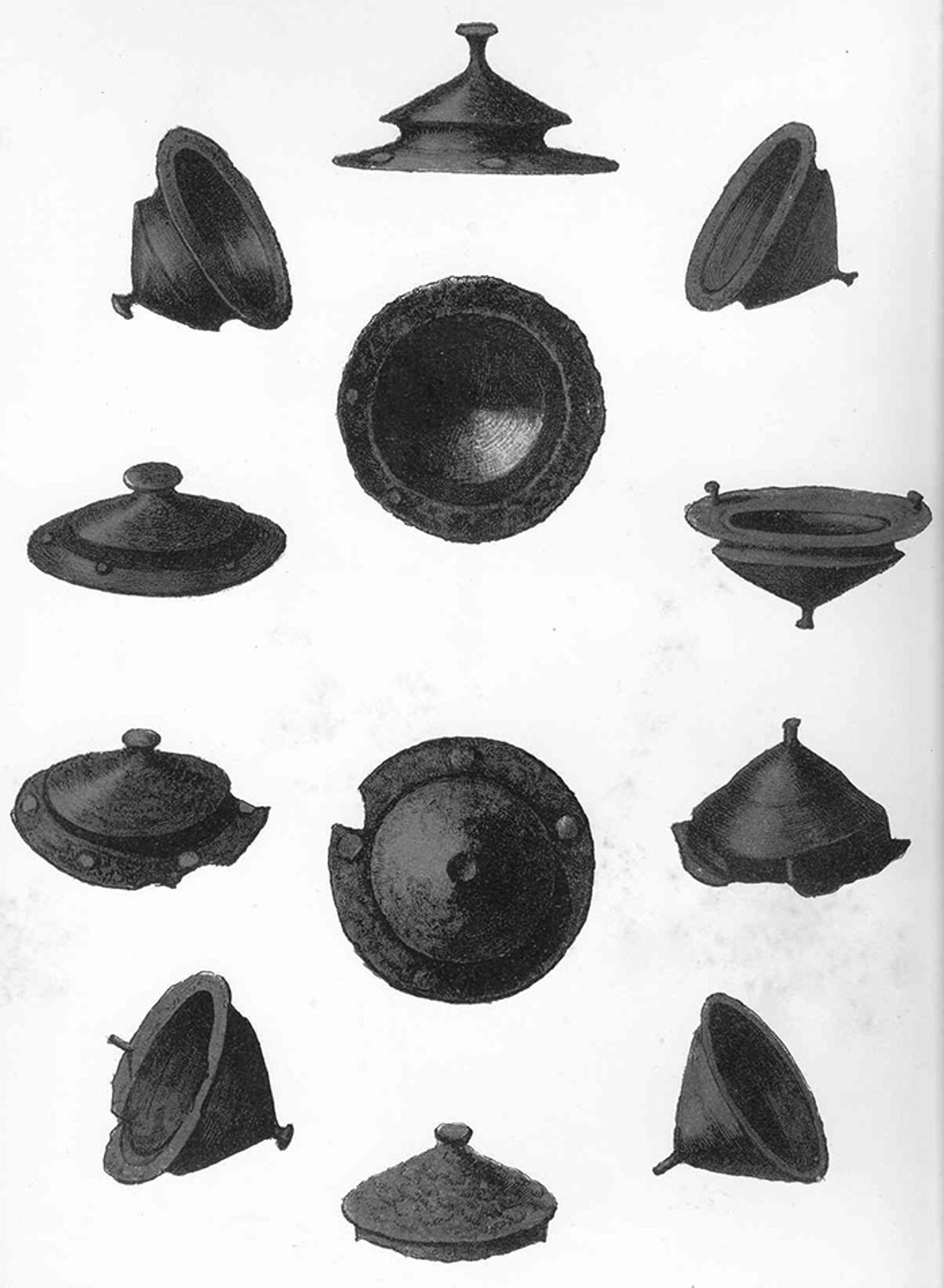

Early archaeologists began commonly calling discoveries ‘Anglo-Saxon’ in the late 1840s. The Essex aristocrat Sir Richard Cornwallis Neville excavated cemeteries at Little Wilbraham and Linton Heath, which he described as ‘Anglo-Saxon’ (see Figure 1 below). Neville regarded these cemeteries in Cambridgeshire as evidence of the earliest Germanic settlers arriving after the collapse of Roman Britain. Neville’s work and terminology were both shaped by contemporary racial thinking and romanticised notions of English origins. This label was influential and persistent. When early and mid-20th-century archaeologists tried, from the distributions of pots and brooches, to figure out the paths of the Germanic invasions, they relied on the work of Neville and his contemporaries.

Figure 1: Shield bosses (or centrepieces) from excavations at Little Wilbraham. From Richard C Neville’s Saxon Obsequies (1852)

Yet from the 1960s and ’70s onwards, the field of Anglo-Saxon archaeology has taken on many fresh questions inspired by a huge increase in data. It has adopted new and advancing methods and techniques of excavation, survey and material-culture analysis. Traditional questions remain and are hotly debated, including the scale and character of Germanic migrations, the timing and nature of kingdom formation, the pace and significance of Christian conversion, and the resilience and response to the Viking raids. Yet they are joined by a host of further investigations and puzzles about Anglo-Saxon social structures and identities, political ideologies and structures, economic activities and connections, and landscape use and management. Moreover, Anglo-Saxon archaeology today sustains long-term collaborations with archaeologists working on comparative themes in other parts of Europe and beyond; and it contributes towards, and participates in, dialogues across disciplines.

As a consequence, archaeologists use ‘Anglo-Saxon’ as a kind of general spatial and temporal term to contain the complexity and variability in early medieval settlements, cemeteries and material culture. We use the subdivisions early Anglo-Saxon (5th to early 7th centuries CE), middle Anglo-Saxon (late-7th to early 9th centuries CE) and late Anglo-Saxon/Anglo-Scandinavian (late-9th to mid-11th centuries CE) as an unexceptional and neutral piece of terminology, or shorthand. We also use the terms ‘post-Roman’, ‘late antique’, ‘insular’ and ‘early medieval’. All these are as imperfect as ‘Anglo-Saxon’, but together they are helpful in conveying information about the date, region and (sometimes) the styles of material evidence being studied.

When archaeologists refer to ‘early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries’, ‘middle Anglo-Saxon settlements’, ‘Anglo-Saxon great square-headed brooches’, ‘late Anglo-Saxon coins’ and so on, the term tells us about the objects and sites, when they were made or found. The term has no racial connotation whatsoever. Spurious modern racial categorisations are simply inexplicable and inapplicable for the early medieval period. Archaeologists sometimes use ‘Saxon’ to refer to southern England, and in other instances archaeologists use ‘Anglian’ to refer to eastern and northeast England. The term is not simply used by scholars, but is widely used in public engagement and education, from museum displays to open and accessible databases of archaeological finds.

Like most disciplines, archaeology has inherited pieces of the racist and colonialist past. Ironically though, it was the British obsession with overseas civilisations that helped to push the first generation of Anglo-Saxon archaeologists in the early Victorian era, including Charles Roach Smith and John Yonge Akerman, to look at English origins. Anglo-Saxon history and archaeology are today taught widely in UK schools, and disseminated via television, news media, social media and popular books, as well as attracting millions of visitors annually to museums and heritage sites.

There are a host of passionate, long-lasting re-enactors who strive to recreate aspects of Anglo-Saxon life, such as the society Regia Anglorum in England. For an array of amateur enthusiasts and faith groups (Pagans and Christian), the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ are important and meaningful. For example, the discovery and display of the Staffordshire Hoard combined in 2018 with the 1,100th anniversary of the death of Æthelflæd of Mercia to cultivate a renaissance in Midlands English pride focused on the Anglo-Saxon past. As a recent BBC History Magazine article by Michael Woods and a BBC Radio 6 interview with Bonnie Greer made clear, new immigrant communities in the UK are not excluded by the term. In short, there are many ways that people today experience and appreciate the history of the Anglo-Saxons without an element of any narrow ethnonationalist or racist perspective.

Indeed, the past 30 years can be described as something of a golden age for Anglo-Saxon archaeology, with a host of exciting new discoveries and innovative research projects addressing a wide range of research themes. Specifically, in my field of burial archaeology, we’ve overhauled our understandings of long-term continuities and transformations from the Roman period through to the later Middle Ages. Rather than equate grave-goods with past ethnic groups, for instance, specialists of early Anglo-Saxon burial archaeology reveal fresh insights into the lives and deaths of early medieval people. Scholars study these materials to better understand gender, kinship and social memory. One notable case study of this is the long-term research projects at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk led by the archaeologist Martin Carver, and more recently the excavation of the adjacent Tranmer House cemetery. Together, these field investigations overhaul our understanding of the far-flung connections and mortuary ideologies of the emergent East Anglian kingdom in the late-6th and early 7th centuries CE.

The publication of 52 essays in The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology (2011) showcased the breadth and depth of current research themes and approaches, from the complexity of settlement organisation and hierarchy to craft technologies and how they changed, to what burial evidence reveals about changing perceptions of identity, from infancy to old age. Meanwhile, in their 2013 book on Anglo-Saxon graves and grave-goods, Alex Baylis and her co-authors provide a new chronology for the 6th and 7th centuries, demonstrating the interdisciplinarity and innovative methods of Anglo-Saxon archaeology. Carver’s island-wide odyssey Formative Britain (2019) puts the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in a broader purview, looking to Wales and the South West, but also to northern Britain and the Picts in particular. And Keith Ray and Ian Bapty’s book Offa’s Dyke (2016) is an example of detailed analysis of a specific site, showing us that Britain’s longest and greatest early medieval monument was an expression of political ideology and hegemony, carefully designed to dominate the landscape and intimidate rivals. Meanwhile, The Sword in Early Medieval Northern Europe (2019) by Sue Brunning, a curator at the British Museum, considers how these portable Anglo-Saxon and Viking artefacts were attributed personalities of their own through their wearing, wielding, exchange and display, as well as in burial with the dead. These are all works in ‘Anglo-Saxon’ archaeology, rich in ideas and data, and supported with rigorous interpretive frameworks.

Public archaeology for the Anglo-Saxon period is healthier than ever

In addition, startling new discoveries use the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ within the context of cutting-edge research of international importance. The Museum of London Archaeology report on the Prittlewell Princely Burial in Southend-on-Sea is an example of high-quality commercial-sector archaeological research (on the excavation of a late-6th-century East Saxon chamber-grave) published alongside a popular book in 2019. That year also saw the publication of The Staffordshire Hoard: An Anglo-Saxon Treasure (2019), which offered new insights into the weapon fittings and other gold, silver and garnet fragments in that discovery (see Figure 2 below), as well as a book on the much-lauded fieldwork project investigating an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Barrow Clump on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. As part of Operation Nightingale, that dig yielded exciting new discoveries, but it was also innovative in incorporating the rehabilitation of wounded British Army veterans through their participation in field investigations (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 2: Early 7th-century gold and garnet seax (or knife) fitting with animal interlace, from the Staffordshire Hoard. Courtesy Wikipedia

Figure 3: Excavation of an early Anglo-Saxon inhumation grave at Barrow Clump in 2018 by military veterans. Photograph courtesy of Harvey Mills ARPS

Through participation on digs and digital dissemination, public archaeology for the Anglo-Saxon period is healthier than ever. The Durham University/Dig Ventures collaboration on excavations is revealing the Anglo-Saxon monastery of Lindisfarne; their website invites us all to ‘join the search for the heart of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria’. Likewise, Catrine Jarman’s high-profile investigation of the Mercian monastic site and Viking winter camp at Repton in Derbyshire has featured prominently in the academic journal Antiquity, as well as in newspaper headlines and the Channel 4 documentary Britain’s Viking Graveyard (2019) (see Figure 4 below). Projects such as Jarman’s rely on the contrast between ‘Anglo-Saxon’ and ‘Viking’ to convey to the public clear distinctions in the archaeological evidence. Likewise, the long-term research involving close liaison between metal-detector users and archaeologists at Rendlesham in Suffolk has identified an East Anglian royal centre. Public engagement has been integral to the inception and development of this innovative research project, and the National Lottery Heritage Fund is now supporting a four-year community archaeology project called ‘Rendlesham Revealed: Anglo-Saxon Life in South-East Suffolk’.

Figure 4: A fragment of stained window glass from the Mercian monastery of Repton, destroyed by the Vikings in 872-3. Photograph courtesy of Catrine Jarman

The public can access detailed evidence and interpretations about Anglo-Saxon archaeology like never before, via the Archaeology Data Service at the University of York. Some invaluable online and open-access academic resources are available for the period and deploy the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ effectively and responsibly. An example is the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture at Durham, which provides a rich photographic database of early medieval carved and sculpted stones from across England, together with detailed scholarly interpretation.

Anglo-Saxon archaeology is popular and public-facing, with academics such as Duncan Sayer writing online about ancient DNA and burial archaeology, and Caitlin Green blogging and Tweeting about the far-flung reach of the Anglo-Saxon world. Across England, one can meet the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ in museums, for example in Room 41 at the British Museum, and at visitors’ centres, such as Sutton Hoo, West Stow or Jarrow Hall, formerly Bede’s World. Numerous city, town and county museums have important collections and display Anglo-Saxon finds in engaging fashion, including the Norwich Castle Museum.

The description ‘Anglo-Saxon’ has long been a difficult one, used by political extremists and in old-fashioned, simplistic and pseudoarchaeological narratives. Furthermore, it clearly means very different things to different audiences. Scholars are right to question its connotations and legacies. Certainly, ‘Anglo-Saxon’ is but one of a host of early medieval terms we use with potentially dangerous and misleading racial or nationalist associations, including ‘Celtic’, ‘Germanic’, ‘Viking’ and others. Yet the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ has long been detached from its racist 19th-century guise. For archaeologists today, it has been effectively ascribed to a wide range of material cultures, sites, monuments and landscape features between the 5th and 11th centuries CE, and used to help craft distinctive narratives about the early medieval past. We are in a golden age for Anglo-Saxon archaeology – we should preserve its story in a careful and critical fashion, rather than abandoning this fascinating period and its many intriguing and informative sites, monuments and landscapes.

By casting all uses and users of the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ as ‘racist’, the academic lobby to ditch the term risks alienating scholars, commercial archaeologists, the heritage sector, stakeholder communities, faith groups and enthusiasts, as well as potential future researchers, from a popular field. Hence, rather than leave ‘Anglo-Saxon England’ to become a playground for extremists, populists, self-publicists and fantasists, we have a scholarly duty to re-energise our efforts to pursue and disseminate rigorous research and modes of public engagement that leave no space for false narratives and make clear the discipline is open to all. Rather than a ‘post-“Anglo-Saxon” melancholia’ where we ‘start again’ from scratch without the term, as some scholars have suggested, Anglo-Saxon archaeology can continue to revaluate and reconfigure its strengths in delivering both detailed original research and public outreach.

This is why I have signed a joint statement by more than 70 experts, and have been contributing articles to other magazines, maintaining that we must stay with, and fight for, the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ and ‘the Anglo-Saxon period’, challenging academic and popular misconceptions and misuses. In this regard, those proposing that we replace ‘Anglo-Saxon’ with ‘Early English’ and ‘Old English’ risk peddling a linguistic and nationalistic emphasis far more open to misuse than ‘Anglo-Saxon’. Particularly, ‘English’ confuses language and perceived ethnicities past and present; adopting it for archaeological material and monuments is ill-considered at best. As such, I remain an advocate of the critical, cautious but widely established and understood use of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ as a gateway, open to everyone, for exploring the complex and diverse material worlds of the mid- to late-1st millennium CE. To paraphrase the motto of the Council for British Archaeology, I advocate that we should work towards an ‘Anglo-Saxon archaeology for all’.