The hero of Thomas Hardy’s tragic novel Jude the Obscure (1895) is a poor stonemason living in a Victorian village who is desperate to study Latin and Greek at university. He gazes, from the top of a ladder leaning against a rural barn, on the spires of the University of Christminster (a fictional substitute for Oxford). The spires, vanes and domes ‘like the topaz gleamed’ in the distance. The lustrous topaz shares its golden colour with the stone used to build Oxbridge colleges, but it is also one of the hardest minerals in nature. Jude’s fragile psyche and health inevitably collapse when he discovers just how unbreakable are the social barriers that exclude him from elite culture and perpetuate his class position, however lovely the buildings seem that concretely represent them, shimmering on the horizon.

By Hardy’s time, the trope of the exclusion of the working class from the classical cultural realm, especially from access to the ancient languages, had become a standard feature of British fiction. Charles Dickens probes the class system with a tragicomic scalpel in David Copperfield (1850). The envious Uriah sees David as a privileged young snob, but he refuses to accept the offer of Latin lessons because he is ‘far too umble. There are people enough to tread upon me in my lowly state, without my doing outrage to their feelings by possessing learning.’

It is with good reason that education in the Classics was and still is associated in the British mind with the upper classes. Since the late 17th century, when the discipline of ‘Classics’ as we know it emerged, only parents of substantial means have been able to buy their teenaged children (and, until the late-19th century, only their male children) the leisure and lengthy tuition that a thorough knowledge of the Latin and Greek languages requires. Classics emerged to provide a curriculum that could bestow a shared concept of gentlemanliness on the new ruling order after the Glorious Revolution. This was composed of Tory hereditary aristocrats in a new alliance with the Whiggish mercantile bourgeoisie. The sought-after ‘classical education’ could now be purchased not only at one of the tiny group of richly endowed all-male boarding schools but at one of the new small private schools in which the 18th century saw an exponential growth. Most were run by Anglican priests, offering a classical curriculum to provide the patina of gentlemanliness as well as access to Oxford and Cambridge.

Even the language used to define class difference was derived from the ancient languages. ‘Classics’ and ‘class’ share a lexical stem that relates them to ancient Roman tax bands. Upper-class snobs call their perceived inferiors hoi polloi (‘the many’, a classical Greek term for the ruling majority in a democracy) or plebeians or plebs (Roman citizens who were not patrician). But there is another dimension to the chronicle of access to classical material in Britain, for non-elite individuals and groups across the same historical period persistently attempted, with varying degrees of success, to educate themselves in ancient Greek and Roman civilisation and languages. For every Jude Fawley and Uriah Heep, there has been a working-class autodidact like Charles Kingsley’s Chartist hero in Alton Locke (1850), an impoverished tailor who does eventually improve his socioeconomic situation. He also comes to a greater understanding of his historical moment by teaching himself classical languages and literature with the help of a Scottish working-class intellectual who is a thinly disguised Thomas Carlyle.

Working-class libraries and archives, the writings of autodidacts and the annals of adult education have been analysed by several scholars since Richard Hoggart’s pioneering The Uses of Literacy and R D Altick’s The English Common Reader, both published in 1957; the most famous, focused primarily on literature in English, are David Vincent’s Bread, Knowledge and Freedom (1981) and Jonathan Rose’s The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (2001). But classical materials have also been present in the identity construction and psychological experience of substantial groups of working-class Britons. Dissenting academies, Nonconformist Sunday schools and Methodist preacher-training initiatives all encouraged those who attended them to read widely in ancient history, ideas and rhetorical handbooks. Classical topics were included on the curricula of Mutual Improvement Societies, adult schools, Mechanics’ Institutes, university extension schemes, the Workers’ Educational Association, trade unions and the early Labour Colleges. These initiatives did much to counter the sluggish legislative response to workers’ demands for education: it was not until the Elementary Education Acts of 1870 and 1880 that even rudimentary instruction in literacy and numeracy, let alone access to classical culture, became universally and freely available to children under 13.

But there had long been other ways to learn about the Greeks and Romans. Museums in Britain were visited by a far wider class cross-section than their Continental equivalents, where the admission of visitors to the princely galleries was closely monitored. There was a sense that art and archaeology somehow belonged to the nation rather than exclusively to wealthy individuals; free admission was customary. A Prussian traveller in London was disturbed to find in 1782 that the visitors to the British Museum were ‘various … some I believe, of the very lowest classes of the people, of both sexes, for as it is the property of the nation, everyone has the same right … to see it, that another has’. And classical sculptures such as the Parthenon frieze and the Venus de Milo were endlessly reproduced in forms accessible even to the poorest Briton: plaster reproductions in municipal museums across the nation, cheap self-education magazines such as Cassell’s Popular Educator, and volumes published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, available in libraries of Mechanics’ Institutes. Lower-class visitors’ memoirs often imply that what they saw in museums nurtured an impulse towards self-education.

Spartacus was adopted as the hero of the proletariat as well as Abolitionism

If the history of British experience of classical materials other than artistic and archaeological ones is widened to include a working-class perspective, it emerges that ancient history, literature and philosophy were pored over by many non-elite consumers as well. The revolutionary democrats of the 1790s, the radical journalists of the crisis at the end of the Napoleonic Wars and in the aftermath of Peterloo, the Chartists, the early trade unionists and the founders of the Labour Party – they all had their own historians who rewrote the histories of ancient Greece and Rome from the perspective of slaves and the poor. The ancient authors central to this alternative version of Greek and Roman history included Livy, especially his account of the heroes of the early Republic, and Plutarch. Brutus: or, The Fall of Tarquin, a popular tragedy by John Howard Payne, premiered at Drury Lane in December 1818, at a time when the British monarchy was at its most unpopular for centuries. Frequently revived, Brutus toured demotic theatres in the provinces, and its text circulated in working men’s reading societies.

Plutarch’s Solon was admired as the wise leader who cancelled peasants’ debts to rich landowners; Spartacus as described in Plutarch’s Life of Crassus was adopted as the hero of the proletariat as well as Abolitionism by the 1830s; Irish Republicans, Chartists and trade unionists alike consumed numerous versions of the lives of the Gracchi brothers, who tried to redistribute land to the Italian poor. The Gracchi also featured in a collection of Plutarch’s biographies rewritten by the socialist freethinker Frederick Gould, The Children’s Plutarch (1906), with engravings by Walter Crane. Gould had taught in board schools in underprivileged London districts, developing a programme for teaching secular ethics with classical instead of Christian literature: in his subsequent volume, Pages for Young Socialists (1913), published by the National Labour Press with a preface by Keir Hardie, Gould uses classical sources to inspire his intended audience, including Herodotus on Thermopylae, Xenophon’s idealised marriage in his Oeconomicus, and the caricature of the plutocrat Trimalchio in Petronius’ Satyricon.

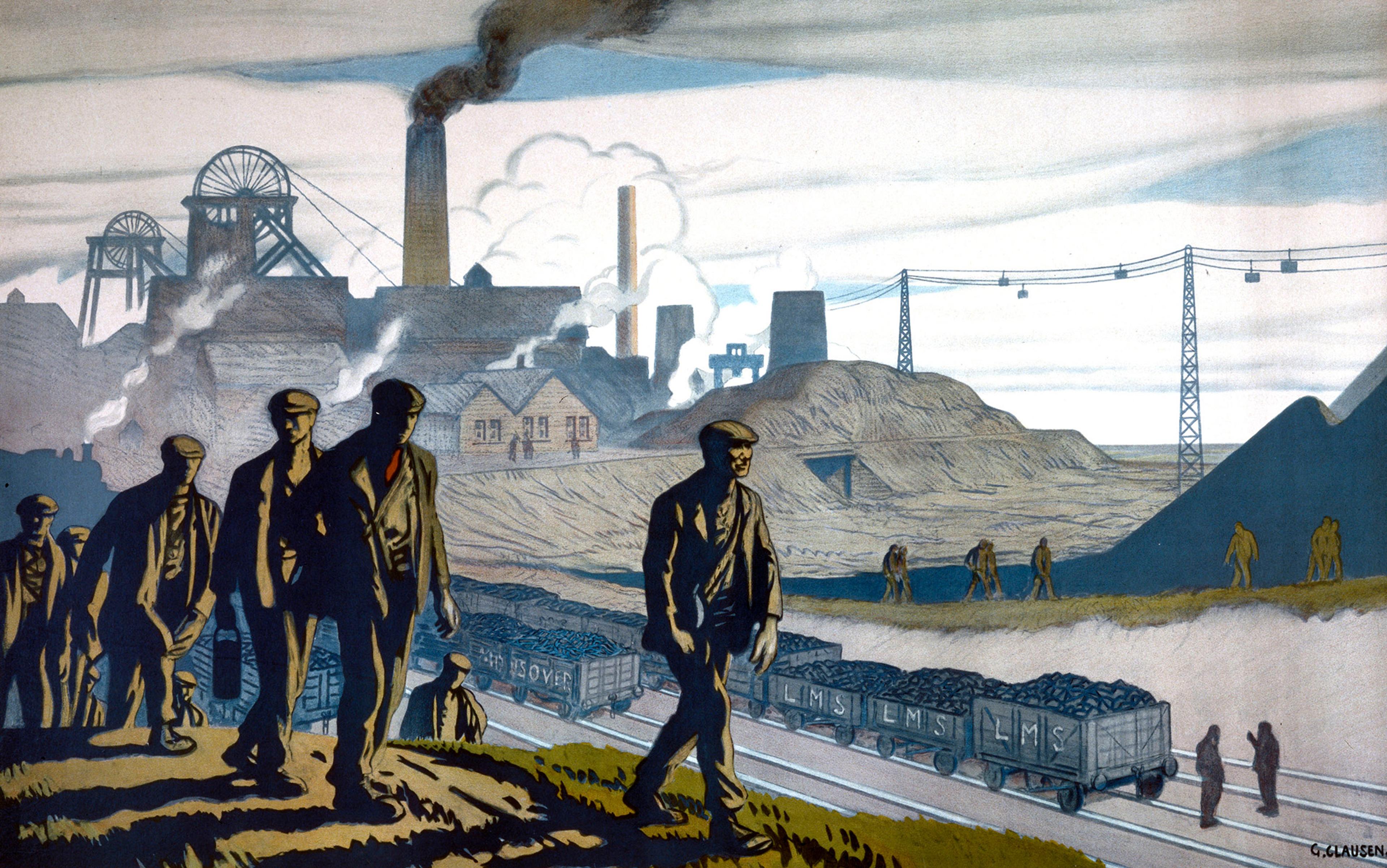

Once the classical Athenian democracy became an acceptable constitutional ideal by the late-1820s, Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War moved to the centre of the working-class autodidact’s curriculum: a young miner who was a member of the Ashington Debating and Literary Improvement Society in Northumberland, and who was killed by a fall of coal in 1899, died with a translation of Thucydides in his pocket, the page turned down at Pericles’ funeral speech.

The nub of the controversy over classical education has always been whether it ‘counts’ to read classical texts in modern-language translation. By 1720, the battlelines had been drawn up. Britons who were unable or unwilling to bankroll their sons’ classical educations fought back. The Greeks and Romans could be approached by routes that didn’t require years glued to grammars and dictionaries. They could be read in mother-tongue translations, by great poets such as John Dryden and Alexander Pope, even though this was obviously derided as a vulgar mode of access to the Classics by those who had purchased the linguistic training. The material covered in ancient authors could be enjoyed even by the completely illiterate in accessible entertainments such as travelling booth theatres and fairground shows.

Pope’s translations had brought Homer to a larger audience, including workers and women, than had ever had the opportunity to learn Greek. Take Esther Easton, a Jedburgh gardener’s wife, visited by the poet Robert Burns in 1787. He recorded that she was ‘a very remarkable woman for reciting poetry of all kinds … she can repeat by heart almost everything she has ever read, particularly Pope’s “Homer” from end to end.’ Pope’s Homer captured the childhood imagination of another Scot, Hugh Miller, a stonemason and a distinguished autodidact, who became a world-famous geologist. Even as a boy, he saw the Iliad as incomparable literature. He wrote in My Schools and Schoolmasters (1854) that he had learned early ‘that no other writer could cast a javelin with half the force of Homer. The missiles went whizzing athwart his pages; and I could see the momentary gleam of the steel, ere it buried itself deep in brass and bull-hide.’ Pope’s version was crucial in providing access to Homer for the working classes because it was such a commercial success that it quickly filtered down to the bustling secondhand book market, frequented by readers of the lower social orders.

Inexpensive translations remained the main avenue of access to classical authors available to the poor. Reading rooms and workers’ libraries allowed many people to read the same publication: in 1829, it was estimated that one journal might be read by as many as 25 people. As early as 1730, the French philosopher Montesquieu was struck to see that, in England, even a slater would have newspapers brought to him to read on the roofs of houses. And that slater might well have read passages aloud to his less literate co-workers; Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776) was consumed by literate and nonliterate alike, in written and oral form; it was read by public men, but its contents were repeated everywhere – in clubs and schools, and from pulpits.

Lubbock drew up a list of 100 books for a working man to read. The proportion of classical authors is remarkable

A man named Tam Fleck kept the townsfolk of early 19th-century Peebles entranced with tales of the fall of Jerusalem. He owned a copy of Roger L’Estrange’s 18th-century abridgement of Josephus’ The Wars of the Jews, and would tour the households of Peebles reading that narrative ‘as the current news’. Wherever possible, he ended on a cliff-hanger, taking care to break off in the same place at every house, so that all his listeners would be left in the same suspense. This had the effect of turning Josephus into a sort of soap opera.

The Working Men’s College in Gt Ormond Street, London c1850s. Courtesy Wikipedia

There were many cheap mass-market series of ‘classics for the masses’ in the 19th century, and organised working-class educators made full use of them. In London, the Working Men’s College became nationally famous under Sir John Lubbock, its principal between 1883 and 1899. Lubbock drew up a list of the 100 books it was most important for a working man to read. The proportion of classical authors is remarkable: Homer, Hesiod, Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Plutarch’s Lives, Aristotle’s Ethics and Politics, Augustine’s Confessions, Plato’s Apology, Crito and Phaedo, Demosthenes’ De Corona, Xenophon’s Memorabilia and Anabasis, Cicero’s On Duties, On Friendship and On Old Age, Virgil, plays by all the tragedians, Aristophanes’ Knights and Clouds, Herodotus, Thucydides, Tacitus’ Germania, and Livy. In addition, two famous works on ancient history, Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-89) and George Grote’s A History of Greece (1846-56), make it on to the list as necessary reading for any educated person, along with the most popular novel then in existence set in antiquity, Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Last Days of Pompeii (1834). After 1887, the classical riches on the bookshelf of the working-class self-educator can, in large measure, be attributed to Lubbock’s ideal curriculum.

The Working Men’s College as it is today in Camden, London. Courtesy the Working Men’s College

Yet the standout name in translated classics is the Everyman’s Library series, launched by Joseph Malaby Dent in 1906. Everyman’s printed 1,000 titles in its first 50 years. Forty-six are listed as ‘classical’ in genre – most standard works of Greek and philosophy, poetry and prose, from Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations (the first classical text released), through the dramatists and epic poets to Aristotle’s Metaphysics, the 1,000th volume published.

Dent was the son of a Darlington painter-decorator who joined a Mutual Improvement Society and caught the literature bug. With his editor Ernest Rhys, he founded the Everyman label. Born into a middle-class family, Rhys began his working life as a coal engineer at Langley Park in County Durham, where he sought to enrich the lives of his co-workers. To the consternation of his conservative line manager, who considered mineworkers to be interested only in drinking and gambling, he established a library in a derelict worker’s cottage. Plato’s Republic was on the inaugural reading list.

Raised in a working-class family with 11 siblings and educated by Wesleyan Methodists, Dent believed that the world could be improved if people read canonical authors, so the format had to be affordable to factory workers such as Vero Walter Garratt. This man spent every evening he could at Birmingham Central Library, ‘searching for books which put me in company with the literary giants of the past. The Iliad and Odyssey, the advice of Epictetus, the principles of Longinus and the logic of the Dialogues of Plato I studied with particular relish for their wisdom seemed to be capable of modern application.’ Soon, Garratt realised that he needed to buy his own copies, and the only ones he could afford were Everyman’s editions.

Some trades were more likely to produce ardent self-educators: tailors and stonemasons were often self-taught intellectuals, as were shoemakers. They knew that Plato’s Socrates used shoemaker exempla, leading Callicles in Gorgias to protest: ‘By the gods! You simply don’t let up on your continual talk of shoemakers and cleaners, cooks and doctors, as if our discussion were about them!’ Callicles’ objection to shoemakers is because they work for their living and are not leisure-class. But in Memorabilia, Xenophon informs us that Socrates would debate with the teenaged aristocratic youths (who avoided the rowdy marketplace) in the leather-works outside. Simon the Shoemaker was a significant Socratic disciple who composed no fewer than 33 ‘leathern’ dialogues, supposedly written from notes he had made on shoe leather. This tradition meant that British shoemaker classicists tended to prefer philosophical authors to poets or historians.

Samuel Drew (1765-1833) was the son of a Cornish farmer. He was put to work in the fields at seven, and he mined tin too. Taught to read by his self-educated mother, he proved a tireless self-educator, and his metaphysical writings later earned him the soubriquet ‘The English Plato’. At 10, he was apprenticed to a leather-worker; by 22, he was running his own cobbler’s shop. Drew had become known as a sharp-witted debater and a fount of knowledge. The shop was frequented by the horse-keeping local middle classes, who furnished Drew with a supply of books. He listened to disputes between local Calvinists and Arminians, and kept his reading up-to-date. He once hunted for Plato’s Phaedo across Cornwall. He wrote a book long considered definitive – An Original Essay on the Immateriality and Immortality of the Human Soul – which was widely lauded and reprinted many times on both sides of the Atlantic, already reaching five English editions by his death in 1833.

One Welsh shoemaker’s son became a competent classicist before a brilliant career in academic philosophy. Henry Jones (1852-1922) rose through scholarships at Bangor Normal College and the University of Glasgow to hold chairs in philosophy at the universities of Bangor, St Andrews and Glasgow and receive a knighthood. He opened his address to the subscribers of the Stirling and Glasgow Public Libraries – ‘The Library as a Maker of Character’ (1905) – with an inspirational quotation from Benjamin Jowett’s translation of Plato’s Phaedrus. In the opening sequence, Socrates goes for a country walk with Phaedrus after meeting the young man with a book under his arm: ‘I am a lover of knowledge,’ said the ancient sage; ‘only hold up before me a book, and you may lead me all round Attica, and over the wide world.’

Bain, a handloom weaver, got his classical education through some lucky encounters with philanthropists

A very few other working-class men, usually in Scotland – where good, free education was sometimes available even as early as the 18th century – succeeded in leveraging their classical prowess to become professional academics. George Dunbar, a poverty-stricken young gardener from Berwickshire, was in 1806 appointed Professor of Greek at Edinburgh, after studying at the university with the financial support of a local landowner. His admirable Concise General History of the Early Grecian States (1824) consists of 112 fluently written pages covering literature and philosophy as well as history. Its surprises include high praise of Aristotelian ethics (which were then out of fashion) and the hope that more people would study them. Dunbar could be describing his own career when applauding Athenian democracy, which ‘possessed this advantage above all others, that it gave free access to every man, however mean his birth or moderate his fortune, to rise by the force of his talents to the highest situations in the state’.

Alexander Bain, a little later, became one of Scotland’s foremost philosophers, being appointed Regius Chair of Logic at the newly unified University of Aberdeen in 1860. In London in the 1840s and ’50s, he’d made friends with John Stuart Mill and with Grote, the political radical and classical historian; he also lectured at Bedford College for Women. Bain was a handloom weaver who managed to get his classical education only through some lucky encounters with philanthropists and a herculean autodidactic effort. His autobiography creates a picture of a man equally proud of his contributions to working-class education and to academic philosophy: in 1850, he wrote a series of articles in Chambers’s Papers for the People on ancient Greece, including ‘Education for the Citizen’, ‘Every Day Life of the Greeks’ and ‘The Religion of the Greeks’. In 1872, following Grote’s death, Bain prepared Grote’s unfinished work on Aristotle for posthumous publication.

The role played by ancient philosophers in working-class (self-)education and radical thinking has been just as important as that played by ancient art, literature or history. Deists, freethinkers and outright atheists have been inspired by the Presocratics, Aristotle’s ‘unmoved mover’ and Plutarch’s On Superstition. Christopher Caudwell’s major Marxist work on aesthetics and society – Illusion and Reality (1937) – proceeds from the argument between Plato and Aristotle on the relationship between the empirically discernible world (reality) and the worlds conjured up in art (mimesis). Robert Tressell’s socialist novel The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists (1914) is an extended exploration of the portrait of false consciousness that he saw crystallised in Plato’s allegory of the cave. And both these men did most of their classical reading in English translation.

The experiences of classical antiquity by the historical British working class have been messy, complicated and diverse. They have, by turns, been inspirational and depressing, too. But, finally, they can also help us think about the place of the ancient Greeks and Romans within the modern curriculum. Classical education need not be intrinsically elitist or reactionary; it has been the curriculum of empire, but it can be the curriculum of liberation. The ‘legacy’ of Greece and Rome has been instrumental in progressive and enlightened causes, both personal and political. Understanding the ancient world can enrich not only the imagination and sociocultural literacy but also citizenship skills and the power of argumentation and verbal expression. Recovering the working-class classicists of the past can also function as a rallying cry to modern Britain to support the case for the universal availability in schools of classical civilisation and ancient history, and for the revival of the proud tradition of free or affordable university extension schemes across the nation.

Edith Hall and Henry Stead’s book ‘A People’s History of Classics: Class and Greco-Roman Antiquity in Britain and Ireland 1689-1939’ will be published on 31 March 2020 by Routledge Taylor Francis.