‘English-only’ advocacy in the United States dates at least as far back as 1919, when President Theodore Roosevelt declared: ‘We have room for but one language in this country, and that is the English language, for we intend to see that the crucible turns our people out as Americans, of American nationality, and not as dwellers in a polyglot boarding house.’ For Roosevelt, the connection between language and citizenship was explicit and unqualified – if Americans didn’t speak English, they weren’t Americans.

The California senator S I Hayakawa introduced the first ‘English Language Amendment’ (ELA) in 1981, seeking to declare English the official language of the US, while overturning any state or federal statutes requiring the use of other languages. Though this amendment died in Congress, it reappeared in various iterations over time, passing the House in 1996, and finding Senate approval 10 years later, as part of an immigration reform bill that itself failed to become law. Despite these setbacks, the English-only movement remains active, and in 2010, a business man named Tim James ran for governor of Alabama with a campaign promise that the State Driver’s Examinations would be offered exclusively in English. Thirty-one states – including Alabama – have now declared English their only official language and in 2012 both major political parties endorsed the English language in their official platforms, the Democrats touting ‘enhanced opportunities for English-language learning and immigrant integration’, while the Republicans said they ‘support English as the nation’s official language’.

In 1997, citing the most recent Census data, the historical linguist Robert D King noted that 94 per cent of people in the US speak English willingly, making a law totally unnecessary. Mauro E Mujica, chairman of the advocacy group ‘US English’, countered that the figure is actually 97 per cent, and so the law is just common sense. These days, the numbers are similar. Census data published in 2011 shows that about 79 per cent of people in the US speak only English at home. A further 16 per cent claim to speak English ‘well’ or ‘very well’. Such congruence casts suspicion on the premise that the ‘official’ demarcation is just about the need for clear communication. In truth, for many English-only advocates, language has become a stand-in for less palatable sentiments, the fear of changing racial demographics among them.

It has become impolitic to attack a rising Mexican-American population on purely racial grounds, but it remains acceptable to criticise ‘illegal immigration’, policy and language standards. The tactic is neither new nor particularly subtle. Writing in 1753, Benjamin Franklin fretted about the increasing German population by noting that these immigrants are ‘generally the most ignorant Stupid Sort of their own Nation’ and that ‘they will soon out number us, that all the advantages we have will not, in My Opinion, be able to preserve our language, and even our government will become precarious’.

Then, as now, such attitudes support the linguist John Nist’s claim in 1966 that language is used ‘primarily as a means of communion rather than as a means of communication’. Commonality of speech creates a web of connections that hold a people together. Language is a national identity, to be preserved and protected, generally by the expulsion of others. This might even override considerations of race, as the black cultural theorist Frantz Fanon noted in his book Peau noire, masques blancs (1952), published as Black Skin, White Masks in 1967: ‘The Negro of the Antilles will be proportionately whiter – that is, he will come closer to being a real human being – in direct ratio to his mastery of the French language.’

As Fanon argued – and Tim James understood – otherness is multifaceted, and should not be theorised on any one face to the detriment of all the rest. European immigrants, for example, have a long history of cold reception in the US, their foreign tongues or dialects revealing them as other even when their skin tone did not. For German, Polish, Swedish and Irish émigrés, their perceived humanity in America always increased in direct ratio to their mastery of English. For Hayakawa, author of the first ELA legislation, co-founder of US English, and a Canadian immigrant of Japanese ancestry himself, this reality was acknowledged, if slightly spun.

Writing for USA Today in 1989, Hayakawa stressed that English proficiency was necessary if immigrants were to compete and succeed in US markets. Supporting migrants and their children to maintain their mother tongue is, he suggested, a racist policy, as it presumes that certain immigrants are incapable of learning English. ‘Brown people,’ he wrote, ‘like Mexicans and Puerto Ricans; red people, like American Indians; and yellow people, like the Japanese and Chinese, are assumed not to be smart enough to learn English. No provision is made, however, for non-English-speaking French-Canadians in Maine or Vermont, or Yiddish-speaking Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn, who are white and thus presumed to be able to learn English without difficulty.’ Having spent several years living in Maine myself, I can testify that the northern part of the state does feature exit ramps marked ‘Sortie’. But the point is well-taken.

African-Americans and other minority groups hailing from the US might well object to Hayawaka’s point – and Fanon’s. Speaking English, they might argue, does not guarantee humanity in the eyes of individuals or – perhaps more importantly – systems. Being able to communicate in English with police officers, for instance, has not kept young black males from filling the rosters of the US penal complex.

In 1996, the English-only debate acquired a new racially inflected dimension, when a school board in Oakland, California passed a resolution to permit use of Black Urban Vernacular – also known as ‘Ebonics’ – in the curriculum. Since many of the district’s children came from households that spoke this way, the board reasoned, it would be conducive to learning if teachers taught in a language the kids would understand. They further argued that, since Ebonics was structured and spoken like any other language, its place in school texts was no more or less arbitrary than Standard English or Spanish. Critics of the plan argued that Ebonics was nothing more than substandard English. It was also irrelevant to the world of employment, so adopting it in the classroom essentially doomed students to lives in the poor neighbourhoods where they grew up. The opposition won out and Ebonics was dropped.

The case of Ebonics offers a twist on Fanon’s explicit alignment of racial and language differences, because the ideal of a ‘Standard English’ that will unify people across the US, is always and everywhere undermined by the simple reality of regional dialects (as occurs in other countries as well). The English spoken in Georgia, for instance, is very different from that spoken in Massachusetts. Midwesterners in Wisconsin and Illinois use pronunciations and phrases that sound comical to west Texans, and vice versa. But while these variations on a Standard English help to fix regional identities, they do not create the types of problems associated with ‘urban’ dialects.

Ebonics was deeply entangled with white perceptions of black otherness, relating to race, class, morality and violence, thus draping it with an added layer of threat. Even in southern states, a white police officer is more likely to identify with a black driver who speaks regional English in an accent they share, than with one speaking the widely stereotyped urban style. In other words, the other who speaks like me is more likely to win my favour than the other who compounds his otherness by speaking other than me.

We wear the masks we think other people want to see

While Ebonics might be a perfectly intelligible form of English to those who speak it, it goes against the grain of a white-dominated society in which belonging means talking the talk of Standard English. Never mind that ceding one’s language preference effectively means capitulating to the forces of power and oppression. Or that adopting Standard English might feel unreal – using language as a conscious, even self-conscious, performance.

Fanon titled his book Black Skin, White Masks, drawing attention to the performative aspects of language use, while the sociologist Erving Goffman, in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), suggested that all people assume ‘roles’ much like actors on the stage, engineering their self-presentations to create certain impressions in the minds of others. They take up ‘masks’, in other words, to fashion themselves for public reception.

One prerequisite of being an American, as we have seen, is the ability to speak English. This chimes with Goffman’s observation that: ‘A status, a position, a social place is not a material thing, to be possessed and then displayed; it is a pattern of appropriate conduct, coherent, embellished, and well-articulated. Performed with ease or clumsiness, awareness or not, guile or good faith, it is none the less something that must be enacted and portrayed, something that must be realized.’ For Goffman, inclusion and acceptance are goals we work toward, perhaps sacrificing our ‘true’ selves to achieve. We wear the masks we think other people want to see.

Such thinking feeds directly into a more basic question of US identity: are we a ‘melting pot’ or a ‘salad bowl’? Should those who come to US shores assimilate to US culture, or maintain their distinctive cultural markers? The question however is too simplistic: it essentialises both the issue and the nation. To the extent that America has a national culture, it has been shaped by elements that immigrants brought with them. To a significant degree, these were absorbed into an expanding American-ness. While being absorbed, however, they maintained traces of their ancestry. Fidelity to a migrant past is not inherently threatening to a national future.

It would be false to think that there is no price to be paid for those migrants who cannot communicate in English. Here as elsewhere, people who are isolated by language tend – much like poor people, or victims of sexual assault, for example – to get blamed for their condition. Immigrants to the US who cannot or will not learn to speak English are necessarily isolated from their English-speaking fellows. The non-speaker is powerless to contest whatever conclusions they draw. Like the ageing Japanese ‘picture brides’ in Julie Otsuka’s novel The Buddha in the Attic (2011), the non-speaker can find himself increasingly withdrawn from public life.

Language is an organic force, and difficult to control. The troublesome example of official French policy in Quebec offers a cautionary tale

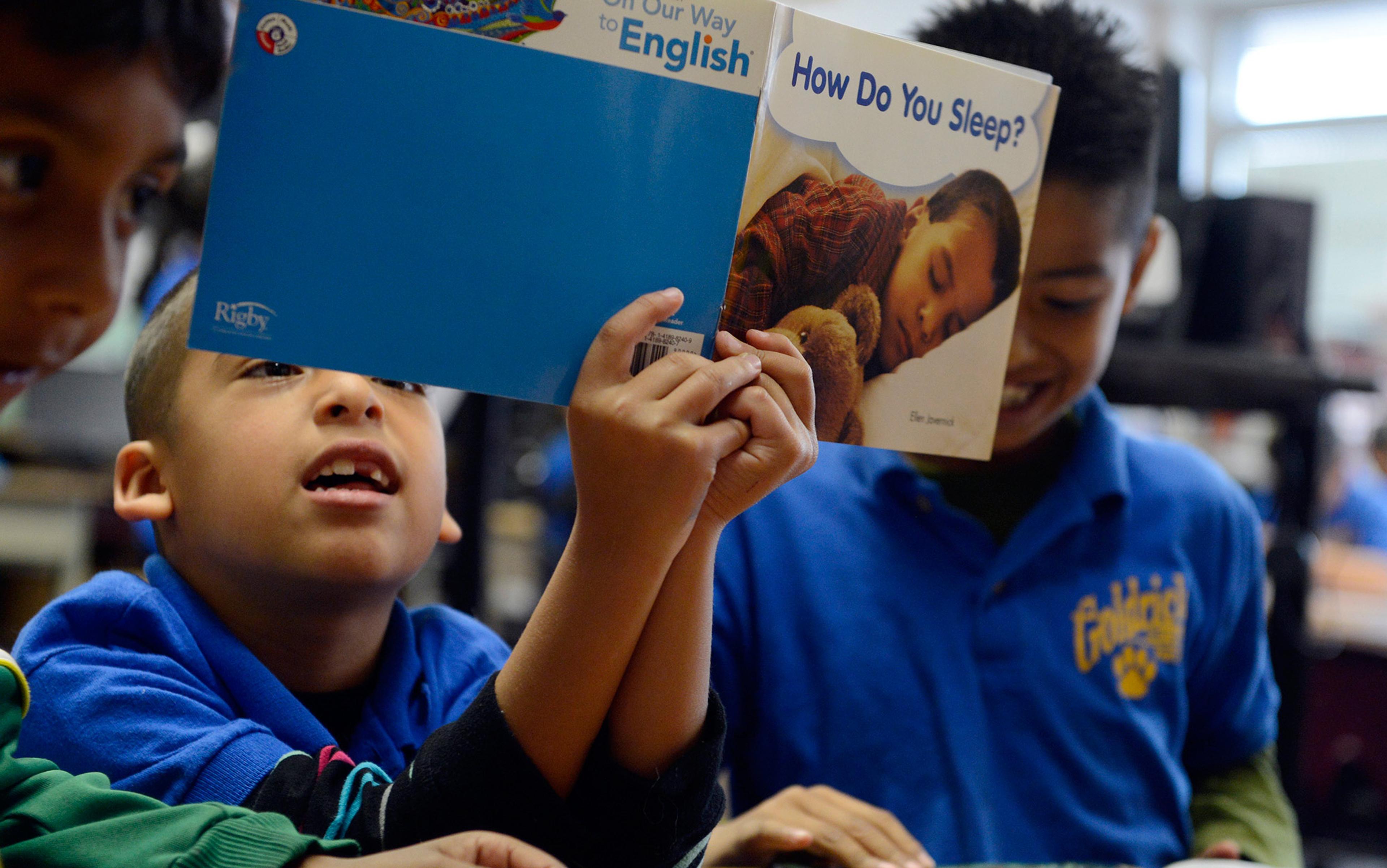

One promising avenue for integrating non-speakers comes in the form of bilingual immersion education. In southern California, home to a broad diversity of ethnicities and languages, such programmes are proliferating. Recently, the Garden Grove unified school district proposed the state’s first Vietnamese immersion programme, geared to accommodating families worried about losing their culture – via their children – to a homogenised American-ness. Such programmes offer a strong rejoinder to the absolutist stance of English-only advocates such as Mujica, who struck a heavy-handed chord during his most recent Congressional testimony, saying (in his slow Chilean drawl): ‘I know firsthand how important it is to know English to succeed in the United States. I have lived this issue, and it is incomprehensible to me that anyone would oppose legislation which codifies the language policy for this country.’

But it is unclear how Official English would solve Mujica’s problem. Instead of making life easier for new immigrants – assuming this is a goal – such a law would likely just bar them from even more opportunities. Likewise, since non-speakers would be further stigmatised, their nativist detractors could claim legal vindication for every exclusionary push. This is Alabama, they might say, we speak English.

Language is an organic force, and difficult to control. The troublesome example of official French policy in Quebec offers a cautionary tale. The US is so much larger, home to hundreds of millions of people and their myriad cultural traditions. Enforcement brings other problems, too, not least ideological ones; many supporters of Official English are political conservatives, critically opposed to government intervention in the lives of citizens. If imposition is to be avoided as a rule, then federal speech codes must surely qualify. And since laws are valid only to the degree that they can be enforced, language law is bound to be tenuous at best.

If the English language were under threat, matters might be different. But any honest appraisal of the situation in the US must concede that it simply is not. At the close of his excellent 1997 essay on the subject, Robert D King said that Americans are ‘not even close to the danger point’, and that we can ‘relax and luxuriate in our linguistic richness and our traditional tolerance of language differences’. Dismissing the idea that language was a threat to unity, he concluded: ‘Benign neglect is a good policy for any country when it comes to language, and it’s a good policy for America.’

Almost two decades later, I see no reason to disagree.