Literature tells us that our desires know no reason. We read Racine’s Phaedra or Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and we see people captured by passion, acting in defiance of all sense or explanation. But science is never satisfied with ineluctable mystery, even in the realm of desire. During the past four decades, researchers into human behaviour have begun to investigate sexual desire. More than anything, they want to know: why is it that we want who we want?

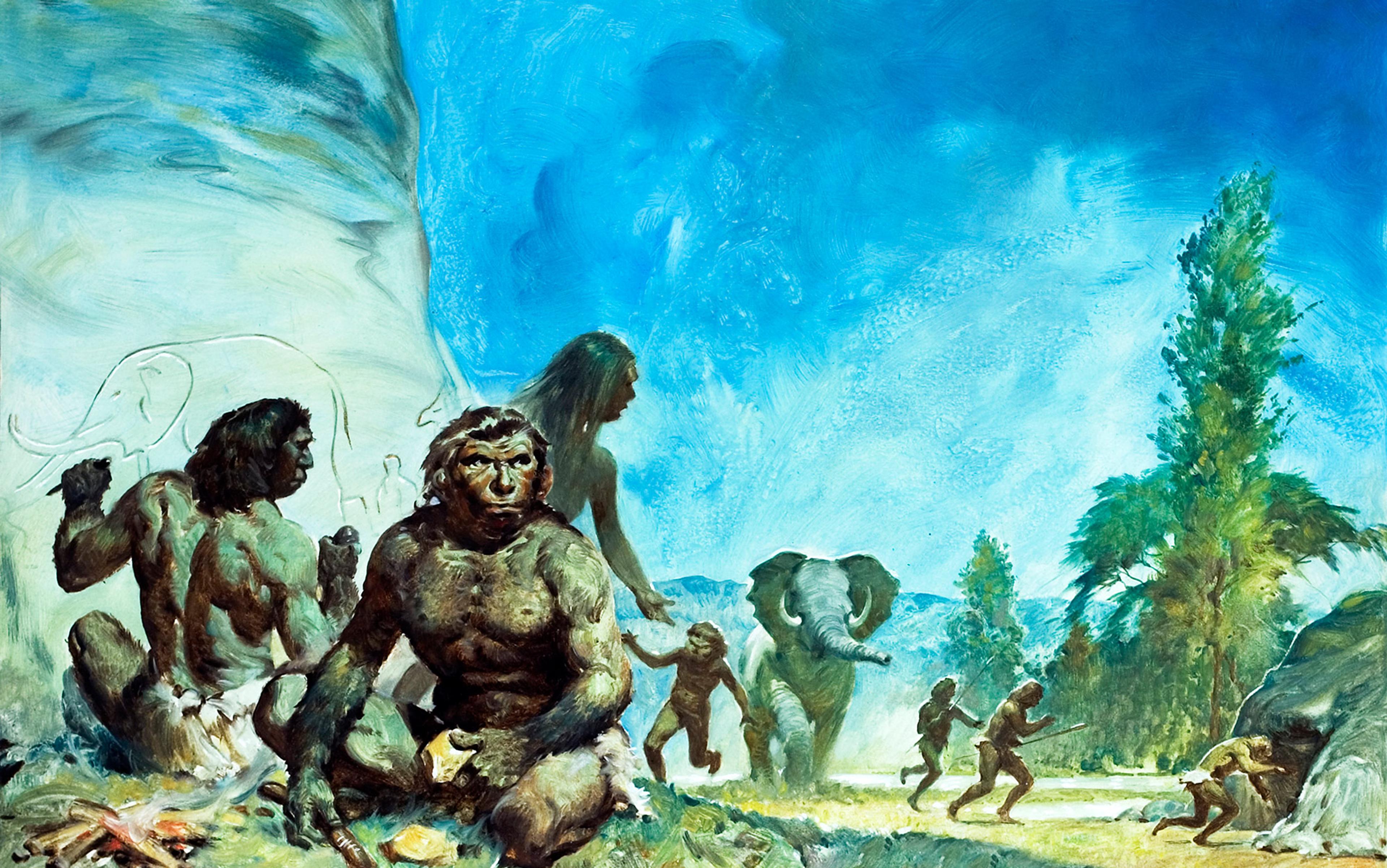

Evolutionary psychology offers one compelling answer to this question. It tells us that, for all its complexity, human desire is the result of something quite simple: our struggle to stay alive. Lust, infatuation, true love – these are all just mechanisms we have acquired in order to reproduce and to keep our children alive. Meaning that, when we look for sex, we are actually, unbeknown even to ourselves, acting in ways that are highly strategic and rational. We are using adaptive techniques that humans developed over our species’ long history, in order to maximise their genes’ chances for survival.

In the four decades since it was first developed, this strategic theory of desire has become a dominant paradigm in psychology, and a familiar feature of media discussions of sexual behaviour. But the strategic paradigm is now facing a challenge from a new generation of evolutionary theorists who have put forth a new story about our species’ past, and new predictions about how we might have sex in the future.

I’ve never had a beard. It would take me forever to grow one, and I haven’t had any reason to try. When I was young, women hated beards. Facial hair was seen as a 1970s thing – something your dad or Burt Reynolds might wear. Then, one day, there were hipsters and, within a few short years, magazines were filled with bearded models, and razor-makers were in a panic over falling sales.

The New York Daily News concluded in an August 2013 article that ‘the country’s recent fondness for the full beard goes back less than two years to a small number of trend setters’. But the article made no mention of a study on beards and desire published earlier that year in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior. The study’s authors, Barnaby Dixson and Robert Brooks of the University of New South Wales in Australia, showed a series of photos, depicting men with different kinds of facial hair to a group of women, and asked them to rank the photos in terms of attractiveness. The women said they liked beards, but not, according to the authors, because beards are in fashion. Rather, the weak preferences of the study’s participants were taken to show that women have been programmed by evolution to pursue men with facial hair. Beards apparently signal age, maturity, industriousness, aggression, dominance, and ambition – all traits than women are innately attracted to.

In reaching its conclusions, the study applied what has become the standard paradigm in evolutionary psychology. This paradigm says that our real-world sexual choices tend to reflect biological imperatives that have, over the course of millions of years, programmed men and women to approach sex very differently. For women, pregnancy is a difficult, costly process, and raising children even more so, meaning that sex must be taken seriously. By and large, biology conditions women to avoid casual sex and to connect sex with love. It also pushes them to look for good providers who tend to be older and wealthier.

Humans have adapted to a wide variety of ecological niches, and part of that could be due to our sexual plasticity

Men, on the other hand, have lots of love to give at no cost to themselves, and they behave in ways that will spread their genes as widely as possible. On this theory, men will settle down with a woman who is fertile and whose fidelity is assured, in order to have legitimate offspring. But they will also sleep around as much as they can, especially with women who possess the key ‘fertility cues’ of youth and physical beauty.

Someone who reads only the media coverage might wonder why anyone takes the evolutionary study of sex (ESS) seriously. It is easy to caricature, and many of its followers seem intent on doing the job themselves. In the past couple of years, evolutionary psychologists have been able to grab reporters’ attention by suggesting, for instance, that men with smaller testicles make better fathers, that men with attractive partners perform oral sex more often because they’re checking for competitors’ sperm, and that women have orgasms in order to attract mates willing to commit to raising offspring. Stories such as these have given plenty of ammunition to critics of ESS and, as a result, many people now dismiss it out of hand. And that’s a shame, because the discipline has stimulated some genuinely original thinking about human sexual behaviour. A closer look at its history can give a sense of its sophistication.

The roots of evolutionary psychology can be traced back to Charles Darwin himself, who says in On the Origin of Species (1859) that, armed with the theory of natural selection, ‘psychology will be based on a new foundation’. But it truly came into its own in the 1970s, thanks to Robert Trivers, then a Harvard postgraduate, who wrote a series of papers that helped to define evolutionary psychology as a field. One of these, ‘Parental Investment and Sexual Selection’ (1972), laid out the basic elements of an evolutionary explanation for sexual behaviour. Trivers looked at data from a variety of animal species, and concluded: ‘The relative parental investment of the sexes in their young is the key variable controlling the operation of sexual selection. Where one sex invests considerably more than the other, members of the latter will compete among themselves to mate with members of the former.’

Trivers’s paper looked only glancingly at human behaviour, though it was rich in suggestions for further research. In his book, The Evolution of Human Sexuality (1979), the anthropologist Donald Symons used Trivers’s basic ideas to explain how people make sexual choices. Symons wanted to know what women and men were after when they went looking for sex, and he arrived at a relatively simple answer: ‘Men like sex with strangers … and women generally don’t.’

There is nothing maladaptive about a woman having a casual affair. It’s a great way to get access to strong, healthy genes

Symons was a powerful theoriser, but he had been unable to offer much in the way of actual data. In 1981, an ambitious young Harvard professor, David Buss, read Symons’s book, and decided to look for hard evidence to test its key claims. Though he started with a survey of a few middle-class white people, he was not content, as many of his followers would later be, to stop there. He assembled a group of international collaborators into what he called the International Mate Selection Project, which asked people from 37 different cultures what they looked for in a sexual partner. His collaborators risked their lives to survey Zulu women in remote South African villages and to smuggle information, carefully coded to avoid government censors, out of Communist China. The results, first published in 1990, provided data from close to 10,000 respondents in 33 countries and they revealed some strikingly consistent patterns across a variety of cultures, all more or less in line with Symons’s predictions. Buss used this data as the basis for what he called ‘sexual strategies theory’.

Though the data from Buss’s surveys confirmed the basic hypotheses of Trivers and Symons, the resulting theory introduced some important refinements. Notably, sexual strategies theory pays attention to an obvious fact that earlier evolutionary psychologists had left largely unanalysed: women sometimes want casual flings, too. According to sexual strategies theory, women don’t altogether avoid sex outside of committed relationships, but they use different criteria for choosing partners depending on whether they are engaged in short-term or long-term mating. Women out for casual sex generally place a premium on looks, which signal fertility and genetic health, in contrast to those looking for a long-term partner, who look for someone with status, maturity, and access to resources. There is nothing maladaptive about a woman having a casual affair. It’s a great way to get access to strong, healthy genes, and ones that are different from those of her other children, thereby increasing the family’s overall resistance to disease. She just has to be sly about it, so she can still hold on to her life partner.

Critics of evolutionary psychology have long accused it of crafting theories that work not as predictive hypotheses, but as ‘just so stories’. Such stories take observed behaviour as they find it, and simply speculate about how it might have bestowed some adaptive advantage on early humans. But this charge, when levelled at sexual strategies theory, is unfair, for in the hands of researchers such as Buss, the theory does make predictions – for example, that women will be more likely to pursue hyper-masculine men when they are ovulating than at other times. These hypotheses can then be subjected to confirmation or refutation through data drawn from any cultural context. Indeed, proponents of sexual strategies theory often point out that their chief critics, the ‘social constructionists’ who insist that our sexual behaviour is entirely the result of our cultural conditioning, have a ‘just so’ problem of their own.

Nevertheless, it’s certainly true that even the most robust cross-cultural data cannot show that a given phenomenon is the result of our mental hardwiring. And ambitious cross-cultural studies of the sort that Buss and his colleagues undertook are exceedingly rare. Indeed, an embarrassing portion of the ESS literature is based on surveys of university undergraduates: hardly a reliable sample population for uncovering universal human characteristics. Not only do these people come from a single culture, they come from a narrow subsection of that culture, one that is mostly white, liberal, educated and affluent. College students also operate in an unusual social context, where they are surrounded by large numbers of single people their age, all of them equipped with means of instantaneous communication and social networking, and without any supervision by parents or other familiar elders. As one recent paper put it, these conditions ‘may not have existed during the majority of human evolution’.

Evolutionary psychology has also been criticised for its focus on heterosexual desire. To be fair, natural selection operates by means of reproduction, and so reproductive sex is clearly going to play a crucial role in any explanation of its mechanisms. But humans are not an exclusively heterosexual species, and an adequate theory of desire must explain how people can be oriented, either partly or exclusively, towards members of their own sex. ESS has most commonly seen same-sex desire as a by-product of our evolved, heterosexual mating strategies. On this view, it is the result of traits – such as our tendency to build same-gender alliances in order to solidify our social position – that are adaptive in their origins, but that have, in certain individuals, become distorted or overdeveloped. This account describes homosexuality as a kind of software glitch – one that evolution hasn’t bothered to fix because it isn’t serious enough to crash the entire programme. But not many gays and lesbians are likely to be satisfied with that explanation, and they could be forgiven for wondering whether the problem lies with the paradigm itself.

Among the Na, monogamy is frowned upon, everyone is free to have as much casual sex as he or she wants, and jealousy is apparently unheard of

One could argue that traditional ESS looks at the question of sexual orientation exactly backwards. When we survey the full range of sexual practices across different human societies, we might conclude that the sort of rigid, predictable patterns of desire posited by sexual strategies theory are either nonexistent or maladaptive. Humans have had to adapt to a wide variety of ecological niches, and we have done so with remarkable success, and part of that could be due to our sexual plasticity, which allows us to calibrate our sexual behaviour to fit our environment. Same-sex and bisexual desire are two very visible products of our innate variability but, as the ethnographic record shows, there are many others that fit equally poorly into the standard paradigm.

Two US anthropologists, Katherine Starkweather and Raymond Hames, have recently shown that polyandry, the practice of women taking multiple husbands, is much more common than people in their discipline previously recognised. And Stephen Beckerman at Pennsylvania State University has drawn attention to what he calls ‘partible paternity’, where a woman has sex with more than one man in order to get pregnant, with these multiple partners jointly recognised as fathers of the offspring. This practice is common throughout the lowlands of South America, and other examples can be found around the world. And some cultures, such as the Na (or Mosuo) people in southwest China, don’t seem to have any stable pair bonds at all. Among the Na, monogamy is frowned upon, everyone is free to have as much casual sex as he or she wants, and jealousy is apparently unheard of.

All this shows that we are a weird, wonderful and sometimes downright kinky species. But sexual strategies theorists have never pretended that their model can explain all of our sexual behaviour. Their claim is rather that they can give us a way to distinguish signal from noise. Beneath all of our diversity, the thinking goes, there are certain forms of behaviour, such as stable heterosexual pair bonding, that might not be universal, but which recur with sufficient regularity as to be considered the norm. However, as historians and anthropologists continue to add to the catalogue of anomalies, we need to decide what sort of evidence counts as falsifying the theory. How common does a behaviour need to be before we consider it a norm?

Right now, there is no rival grand theory that promises to explain fully what we might call the ‘variability hypothesis’ – the view that humans are capable of adapting most or all aspects of their sexual behaviour to fit their historical and environmental context. On its own, an appeal to our innate plasticity does no predictive work. A full, predictive theory of variability should tell us, for instance, which sorts of environments produce stable heterosexual monogamy, and which lead to alternative arrangements, such as polyandry or, as in ancient Greece, widespread bisexuality. Until we have such a theory, the variability hypothesis leaves us with yet another dreaded ‘just so’ story. But research on sexual variability is still at an early stage, and we can hope that such a theory will yet emerge. If and when it does, we can pit it directly against sexual strategies theory, and see which of them does a better job explaining the evidence overall.

Even if evolutionary psychologists come up with the perfect theory to link our sexual behaviour to the hardwiring in our brain, many people would argue that it wouldn’t matter much anyway. We would still wake up every morning to be buffeted by desire’s mysterious winds, and we would still be left to cobble together, from our unruly urges and our imperfect decisions, lives that make as much sense to us as possible. Tracing your sexual preferences back to the Pleistocene doesn’t help you decide between the rough boy in the leather jacket and the nice banker who will help with the kids. And yet, when all is said and done, we’re animals – and evolution is the most powerful tool we have for understanding the animal world. Biologists would not try to explain the development of our kidneys or our immune systems without reference to human evolution. And it would be very odd if evolutionary theory had nothing to contribute to the understanding of the human mind.

So we all have an interest in figuring out what will make us sexually happy. Humans in the 21st century, at least those in developed, Western democracies, live in an environment that provides almost complete sexual liberty. And thanks to technology, we can now connect with one another with unprecedented ease. We can see more potential mates in an hour on Tinder than our Pliocene ancestors encountered in their lifetimes. Assuming that we are hard-wired sexually, ignoring that hardwiring will come at a cost. Modern consumers have unlimited freedom when it comes to food. But if they use that freedom the wrong way, they could make themselves obese, and potentially die of a heart attack.

If jealousy is truly hard-wired, then experiments with non-monogamy are doomed to fail

Though evolutionary psychology is often seen as a conservative discipline, dedicated to providing justifications of the status quo, its final conclusions could be quite radical indeed. Researchers might tell us that it’s the accepted norms of our culture that are doing violence to our nature. Indeed, the current best-seller among ESS books, Sex at Dawn (2010) by Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá, two self-described ‘shame exorcists’, is a sustained attack on our society’s norm of monogamy. It surveys the anthropological record, as well as the behaviour of our closest primate cousins, chimpanzees and bonobos, and makes the case that humans actually evolved to be promiscuous. Ryan and Jethá claim that it is only with the advent of modern agriculture, and men’s ensuing need to protect their inheritance, that humans began to expect exclusivity from their partners. They attribute our modern sexual malaise to the mismatch between our Paleolithic libidos and the monogamous straitjacket into which we have forced ourselves.

Sex at Dawn is longer on polemic than it is on data and argument, and the reviews in the specialist journals have generally been negative. But the book has provoked its readers to look again at our culture’s norms surrounding monogamy. Gay men such as the US sex columnist Dan Savage have always found straight society’s obsession with sexual exclusivity somewhat bizarre, considering that people of every orientation experience it as a difficult struggle. And here evolutionary science might genuinely have something to say. If jealousy is truly hard-wired, as sexual strategy theorists claim, then experiments with non-monogamy and what Savage calls ‘monogamishness’ are perhaps doomed to fail. But if jealousy is instead the product of a contingent set of historical circumstances, it might be that our norms need to go.

The 18th-century philosopher David Hume told us long ago that you can’t derive an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’. Two centuries earlier, Montaigne called the art of composing our character our ‘great and glorious masterpiece’, and science can never spare us the burden of this task. Regardless of what evolutionary psychologists decide about our nature, it’s still up to us to choose the lives we want. Yet when it comes to sex, we don’t seem to be especially good at it, which is why so many of us are confused and unhappy. On the bright side, however, we are also in the midst of a massive social transformation that is giving us more sexual freedom than we have ever had before. If evolutionary theory can help us to navigate this dizzying new world, we ought to be willing to listen. After all, we need all the help we can get.