The disparity between top earners and everyone else is staggering in nations such as the United States, where 10 per cent of people accounted for 80 per cent of income growth since 1975. The life you can pay for as one of the anointed looks nothing like the lot tossed to everyone else: living in a home you own on some upscale cul-de-sac with your hybrid car and organic, grass-fed food sure beats renting (and driving) wrecks and subsisting on processed junk from supermarket shelves. But there’s a related, looming inequity so brutal it could provoke violent class war: the growing gap between the longevity haves and have-nots.

The life expectancy gap between the affluent and the poor and working class in the US, for instance, now clocks in at 12.2 years. College-educated white men can expect to live to age 80, while counterparts without a high-school diploma die by age 67. White women with a college degree have a life expectancy of nearly 84, compared with uneducated women, who live to 73.

And these disparities are widening. The lives of white, female high-school dropouts are now five years shorter than those of previous generations of women without a high-school degree, while white men without a high-school diploma live three years fewer than their counterparts did 18 years ago, according to a 2012 study from Health Affairs.

This is just a harbinger of things to come. What will happen when new scientific discoveries extend potential human lifespan and intensify these inequities on a more massive scale? It looks like the ultimate war between the haves and have-nots won’t be fought over the issue of money, per se, but over living to age 60 versus living to 120 or more. Will anyone just accept that the haves get two lives while the have-nots barely get one?

We should discuss the issue now, because we are close to delivering a true fountain of youth that could potentially extend our productive lifespan into our hundreds – it’s no longer the stuff of science fiction. ‘In just the last five years, there have been so many breakthroughs,’ says the Harvard geneticist David Sinclair. ‘There are now a number of compounds being tested in the lab that greatly slow down the ageing process and delay the onset of diabetes, cancer and heart disease.’

Sinclair, for instance, led a Harvard team that recently uncovered a chemical that reverses the ageing process in cells. The scientists fed mice NAD, a naturally occurring compound that enhances mitochondria – the cell’s energy factories – leading to a more efficient metabolism and less toxic waste. After just a week, tissue from older mice resembled that of six-month-old mice, an ‘amazingly rapid’ rate of reversal that astonished scientists. In human years, this would be like a 60-year-old converting to a 20-year-old practically before our eyes, delivering the tantalising dream of combining the maturity and wisdom of age with the robust vitality of youth. Researchers hope to launch human trials soon.

And earlier this year, two teams of scientists – one at the University of California in San Francisco, the other at Harvard – announced that blood from young mice rejuvenated the muscles and brains of their elderly brethren. They also identified proteins in the blood that catalysed this growth, suggesting the possibility of another longevity drug.

Extensive research on centenarians reaching age 100 and beyond show it’s not healthier habits or positive attitudes that contribute to longevity, but largely genes. Now scientists are busily sifting through millions of DNA markers to spot the constellation of longevity genes carried in every cell of these centenarians’ bodies. The hope here is to concoct an anti-ageing pill by synthesising what these genes make.

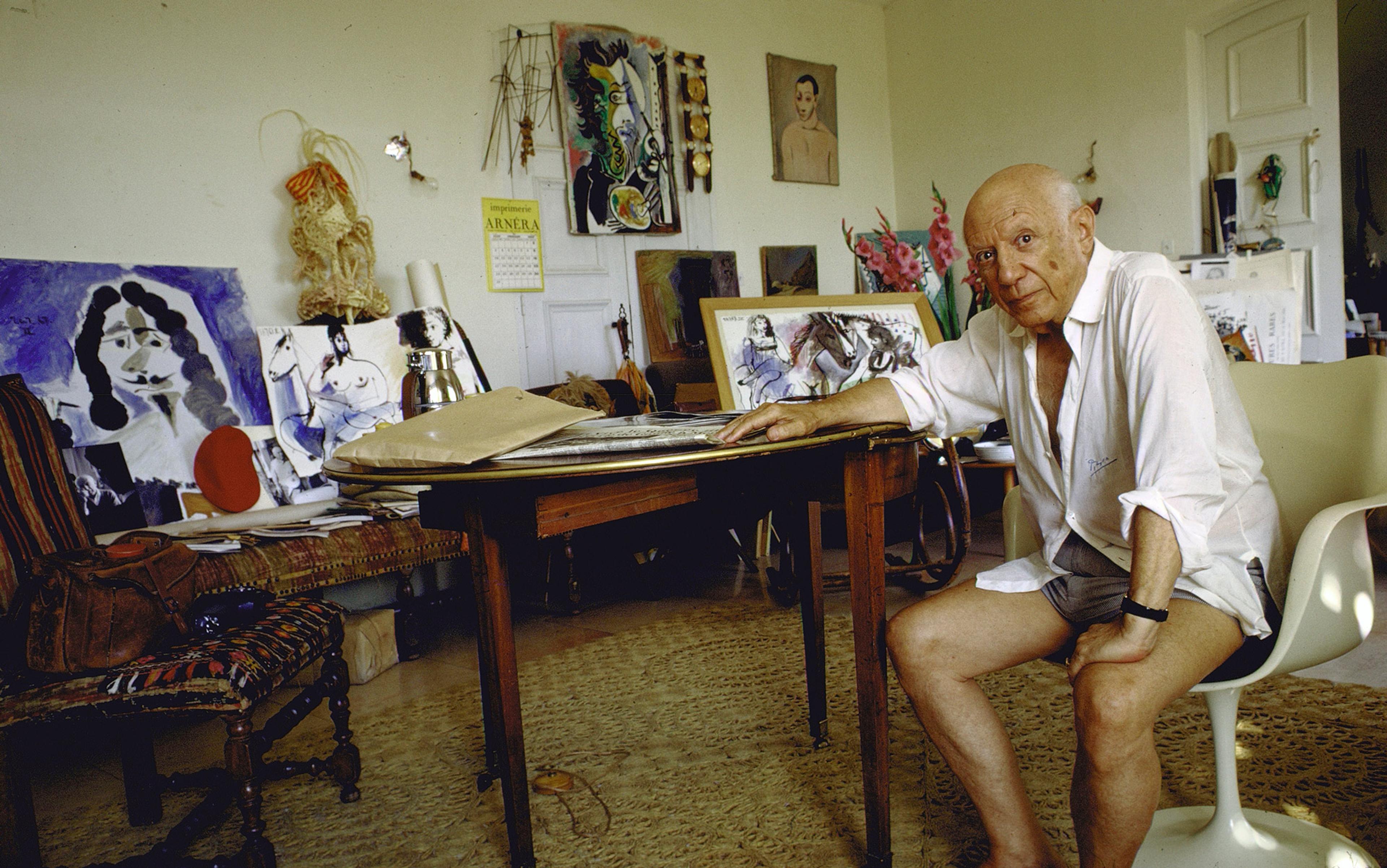

Within the next 50 years, advances in the science of longevity might make the dynamic elderly the rule rather than the exception – think Pablo Picasso, Pablo Casals or Dave Brubeck, all of whom remained dazzling artists or musicians into their ninth decade. People in their forties and fifties today could be the beneficiaries of this seismic shift. ‘It could happen in my lifetime,’ says the 44-year-old Sinclair.

As novel compounds slow or even reverse ageing, the longevity divide could become a gulf as wide as the Grand Canyon. The wealthy will experience an accelerated increase in life expectancy and health, and everyone else will go in the opposite direction, says S Jay Olshansky, a longevity researcher and professor at the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois at Chicago. ‘And as the technology advances, the gap will only grow.’

What will the new world look like? We already have a clue.

Being poor, in of itself, is stressful because it circumscribes every aspect of one’s life. Scraping to come up with routine living expenses – food, shelter, medical care, transportation – can cause chronic insomnia and anxiety, which boosts levels of cortisol, the stress hormone in the blood. This already makes the poor more vulnerable to a cascade of debilitating, life-threatening ills, from diabetes to high blood pressure and heart disease. ‘Poverty is a thief,’ Michael Reisch, a professor of social justice at the University of Maryland, recently told a US Senate panel. ‘Poverty not only diminishes a person’s life chances, it steals years from one’s life.’

In stark contrast, the privileged in the US already have distinct advantages that give them a toehold into a better, longer life. These range from simply growing up in less toxic environments with two financially stable parents to the ability to secure good jobs that provide decent salaries and adequate health insurance. They live in more prosperous communities with less crime and decent public schools, ample doctors and hospitals, better food and nutrition, and superior social services that cushion any fall.

Caleb Finch, a gerontologist at the University of Southern California, calls them ‘the healthy elites’. ‘They engage in health-promoting behaviours, they don’t smoke, and they’re more likely to have time to exercise,’ he says. ‘People who are poor get sick more often. They live in higher-density households, and when one gets sick, everyone gets sick. And these disparities are going to expand.’

To be sure, as baby boomers age, there’s been a great deal of hand-wringing about the swelling ranks of ‘greedy geezers’, the oncoming grey tsunami of the sick and frail elderly who will be an emotional and financial burden on their families and friends, and whose infirmities could bankrupt the healthcare system. The stereotypical image of an octogenarian is someone enveloped in a cloud of confusion tottering around with the aid of a walker – not Clint Eastwood, 84, energetically helming the movie Jersey Boys (2014), or the US Senator Dianne Feinstein, 81, riding roughshod over grandstanding colleagues and even the President himself when she senses an injustice. But hidden in these alarming predictions about the unprecedented ageing of humanity is an entirely different story – about the escalating numbers of people such as Eastwood and Feinstein.

Recent studies show that nearly 30 per cent of people over the age of 85 – a milestone that is often considered the benchmark of the old-old – remain in excellent health, and 56 per cent of them say their health doesn’t stop them from working or doing household chores. In the future, for those who avail themselves of the pricey new drugs, the healthy super-old could be more common at age 100, 120 or more. ‘The experience of ageing is about to change, and older people will have substantially different age-health trajectories than their predecessors,’ says Olshansky – especially if they have access to drugs unlikely to be covered by insurance, since ageing is not a disease.

It could be grounds for revolution if the wealthy lived twice as long while the poor died even younger than their parents did

The 74-year-old Finch could be a candidate for that bounty, if it comes soon enough. Long one of the nation’s leading gerontologists, the lanky scientist shows no signs of slowing down. Sure, he has friends and colleagues who have long since retired – or ‘unplugged’, as he calls it over a salmon salad lunch near his office on the USC campus. It’s an apt metaphor for what I’ve seen happen to lifelong friends who opted for the gold watch when they turned 65, and their gradual retreat from the daily pressures of working life that force us to stay mentally sharp and current. They seem diminished, fading like old pictures from their once vibrant and fully engaged selves.

But for Finch, his career is a fulfilling calling rather than just a 9-to-5 job. His busy office is the nerve centre for a full plate of projects, including a recent scientific expedition to Peru where he autopsied the mummified remains of people who died 1,800 years ago, plus he swims regularly, ever since he was on the Yale University team as an undergraduate.

Think of the drugs that might make all 70-somethings – or eventually 90-somethings – much like Finch. What if the mantra ‘80 is the new 50’ could apply to us all? But the coming longevity gap might set us up for something else instead: a rage-filled conflagration that would make Occupy Wall Street, the US movement against the one per cent of top earners, pale. It could be grounds for revolution if the wealthy lived twice as long while the poor died even younger than their parents did.

Instead of allowing the wealth gap to turn into a longevity gap, perhaps we’ll find a way to use everyone’s talents and share the longevity dividend at all levels of income. This kind of sharing could leverage the wisdom of elders, forestall the economic collapse many have predicted when the grey tsunami picks up speed, and avoid an all-out revolt against the one or so per cent. We stand at the threshold of two distinct futures – one where we have a frail, rapidly ageing population that saps our economy, and another where everyone lives much longer and more productive lives.