I watched both my parents disappear into the sinkhole of dementia before their deaths. Their once-expansive lives were gradually diminished by their growing frailty until all that remained was a tiny room in a nursing home or assisted‑living facility, a lifetime of possessions whittled down to a few photographs and keepsakes. They were utterly dependent on the kindness of strangers who worked for minimum wage.

My mother died first in a cloud of confusion brought on by age and the aftermath of surgery when she shattered her hip in a fall. She never completely recovered from the anesthesia, which robbed her of much of her reasoning abilities. The confident, often-strident woman who ruled our household with an iron fist had been taken over by a confused, frightened child barely able to handle the routine chores of life. Doctors determined she was ‘unable to be rehabilitated’, and she was shuttled from the hospital to a dreary nursing home. She drifted in and out of lucidity, but was cognizant enough to beg my father every day to take her home, and cry bitterly when he left.

After her death, my father moved from Florida to Los Angeles to be near me. In his working life, he had been a civil engineer who had once led the surveying team that had laid out the five corners of The Pentagon, the vast headquarters for the United States military, nearly a mile in circumference. When they finished, using only slide rules, the complex calculations were off by just a few inches: an extraordinary feat comparable to programming the Mars Rover with a calculator.

Yet a few years before he died, he suffered from a galloping dementia that turned his mind into a leaky sieve. His short‑term memory was completely shot, rendering him incapable of learning anything new, even something as simple as how to use the TV remote control.

The accelerating loss of brain cells began to strip away the layers of socialisation and he shed the inhibitions of a lifetime. He would forget he had eaten and would vehemently insist on being served five or six meals a day. He gained 20 pounds almost overnight. Finally, he became incontinent and was unable to perform the daily functions of living without assistance. One day, almost mercifully, his big heart just gave out.

My parents’ experience and the things they learned throughout their lives formed the scaffolding of their identity. The erosion of their memories stripped them of vast pieces of who they were, and I worry that their fate awaits me. The longer I live, the greater the chances that my mind will be sucked into the same abyss.

I am not alone in my fears. For leading‑edge baby‑boomers who are now well past 60, the road has flattened, the fires of ambition have been banked and, barring an unusual late‑career surge, whatever territory we’ve conquered is all we’re going to claim in this life. Now we’re just trying to prevent it all from slip‑sliding away.

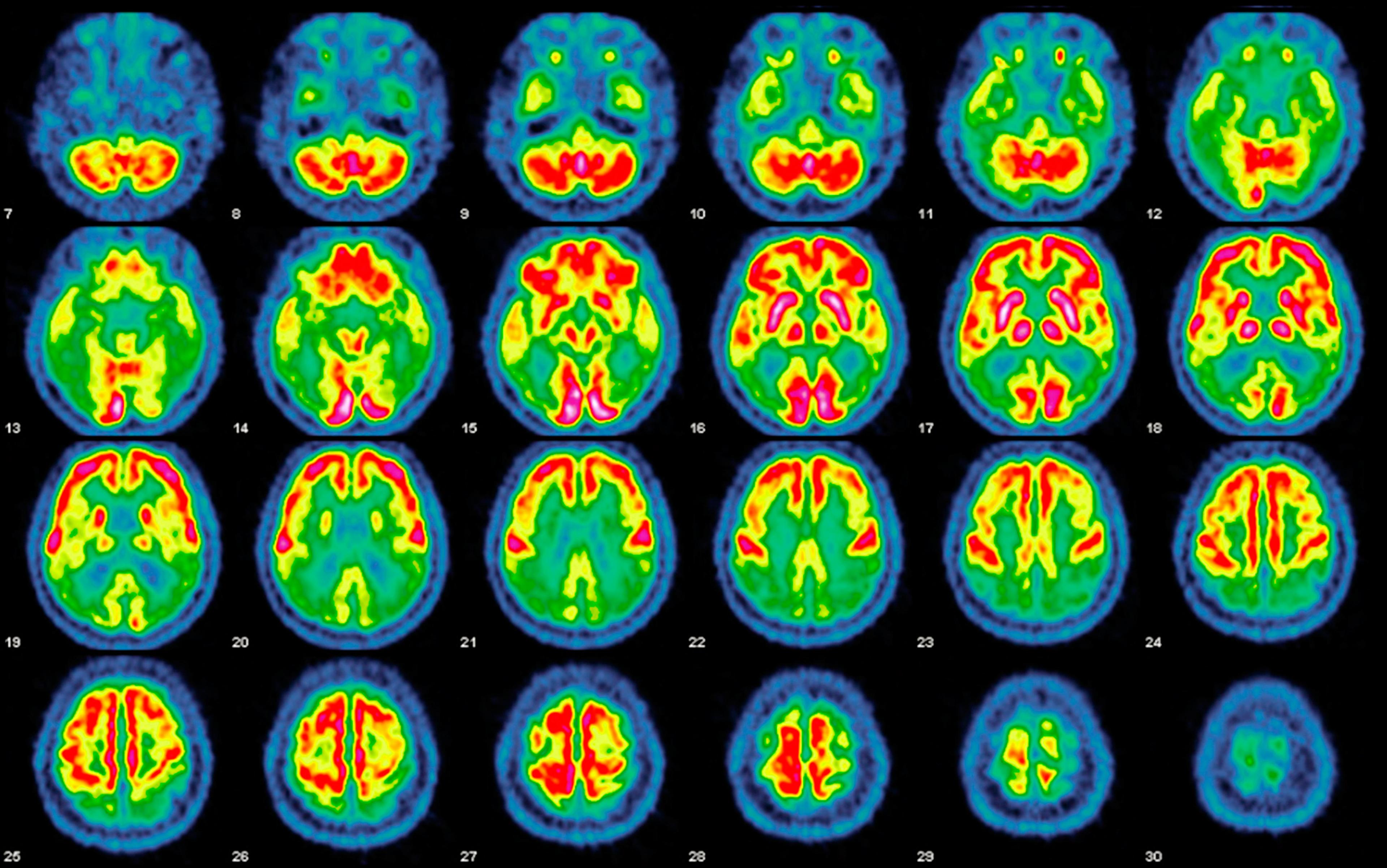

No amount of Botox or Pilates can stave off the loss of brain cells, a steady erosion that began, ironically, in the days when we were part of the Woodstock nation. The brain reaches its maximum weight by age 20 and then slowly starts shrinking, losing 10 per cent or more of its volume over a lifetime. By our 50s, we’re experiencing mild mental glitches, those unsettling ‘senior moments’ when we’ve misplaced the keys for the umpteenth time or can’t remember the name of an acquaintance, all of it symptomatic of the steady erosion of neurons in our brains.

We make feeble jokes about our failing memories, but quietly worry that they are harbingers of something worse – such as scourges from dementia to Parkinson’s, which increase in frequency as we age. No matter how it manifests, the progressive shrinkage of our brain and the faulty wiring in our neural circuitry slowly rob us of our memories, identity and personality, the abilities that give our lives meaning and purpose, and the physical and emotional capacity to fully embrace the world.

All this is magnified by the demographic time bomb that threatens to exhaust society’s resources: by 2050, more than 400 million people worldwide will be aged over 80, many caring for the explosion of friends and family suffering from brain afflictions of varying kinds. The burden could bankrupt our health system – or, new technology based on neural stem cells, the progenitor cells of the nervous system, could intervene, reversing neurodegeneration, healing damaged brains and averting catastrophe in the nick of time.

For years, the dream of using these early progenitor, or stem, cells for repair of the brain has been hindered by stumbling blocks. Early stem‑cell therapies tried in the late 1990s often failed because the body rejected the foreign tissue; patients could no more tolerate foreign embryonic cells without harsh immunosuppressive drugs than they could tolerate donor kidneys or hearts. And in the United States, the use of embryonic stem cells, which are often derived from discarded embryos from IVF clinics, became a flashpoint of intense political controversy, leading to an almost total ban on their use in government‑funded research during the George W Bush presidency.

The situation appeared to resolve in 2006, when Japanese scientists figured out how to reprogram adult cells that had a specialised function, such as skin cells, so that they acted like embryonic stem cells. Called induced pluripotent (iPS) cells, they are created by coaxing these cells to turn on genes normally found in embryonic stem cells, endowing them with the ability to become the cells of all organs and tissues, including neural stem cells. Because iPS cells are derived from our own cells, scientists thought these cells would not be rejected by the immune system. However, in 2011, a team at the University of California, San Diego discovered that abnormal gene expression can cause the immune system to reject some cells derived from iPS cells too, so the rejection problem continued to hamper success.

Finally, stem‑cell researchers found that they could make extraordinary progress in a single, and somewhat surprising, area: the eye. The eye is considered ‘immune privileged’ because it is largely sheltered from attacks by the body’s immune system thanks to a protective barrier of blood vessels outside of the retina. Researchers who transplanted stem cells into the retinas of blind lab animals were able to restore some of their vision without severe immune reactions.

Before long, scientists were looking at other immune-protected parts of the body, especially the spinal cord and the brain. Since then, there’s been an explosion in research, and we’re now tantalisingly close to using neural stem cells to treat some of the worst plagues of old age: damaged retinas and optic nerves, which cause blindness through macular degeneration or glaucoma; memory disorders from Alzheimer’s disease; movement disorders from Parkinson’s; and the wholesale failure to speak or move due to stroke.

‘The stem cells were acting as a fertiliser of sorts for the surviving cells’

For instance, in 2014, the neuroscientist and stem‑cell researcher Timothy Blenkinsop of the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City transferred stem cells from culture to a space behind the retina, where they survived for at least a month, suggesting potent stem‑cell treatments or cures for retinal diseases such as macular degeneration and glaucoma could be in the wings. Taking this one step further, the researchers at the Neural Stem Cell Institute (NSCI) in Rensselaer, New York and elsewhere are working on therapies that stimulate or deliver stem cells directly inside the brain to the damaged optic nerve, often the cause of vision loss due to vascular disorders or end-stage glaucoma. NSCI has bioengineered a technology called stembeads that reawaken native stem cells which might be dormant.

A team researching Alzheimer’s at the University of California, Irvine has shored up memory by transferring stem cells to the brains of mice. To do their work, they compared the performance on a simple memory test of a group of healthy mice with ones who were genetically altered to develop brain lesions that mimic Alzheimer’s. The fit mice remembered their surroundings about 70 per cent of the time, while the recall rate for the impaired animals was a scant 50 per cent. Scientists then injected the hippocampus – the brain region responsible for memory storage – of the injured mice with 200,000 neural stem cells that were engineered to glow green under an ultraviolet light so their progress could be tracked. Three months later, when both groups of mice were given the same test, they scored the same – about 70 per cent recall – while a control group of damaged mice that didn’t receive the stem cells still had significant mental deficits.

Significantly, only a handful – about 6 per cent – of the implanted cells were transformed into neurons, so the beneficial effects didn’t occur because they simply replaced dead cells. Yet there was a 75 per cent increase in the number of synapses – the connections between neurons that relay nerve impulses. Subsequent experiments suggest the stem cells release a protein called brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) that seems to nurse the injured neurons back to health by keeping them alive and functional, and prompt the surrounding tissue to produce new neurites (long, thin structures called axons and dendrites that transmit electrical messages).

In replications of these studies at labs around the world, treated lab animals showed improvements even after months – roughly the equivalent of about a decade in human years. ‘The stem cells were acting as a fertiliser of sorts for the surviving cells,’ says Mathew Blurton-Jones, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine involved in the research. When scientists artificially reduced the amount of BDNF the stem cells produced, the benefit disappeared too.

Similar experiments are ongoing on the Parkinson’s front. In one study from 2014, scientists at the University of California, Irvine transplanted neural stem cells into the brains of mice with Parkinson’s-like disease, enhancing their ability to produce dopamine, the brain chemical that becomes deficient as the disease progresses. Motor and cognitive function dramatically improved. In another study conducted just this year, the International Stem Cell Corporation (ISCC) in Carlsbad, California implanted another type of neural stem cell – called a human parthenogenetic stem cell, derived from unfertilised eggs – in two types of animals (rats and green African monkeys) with induced Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Their study showed that the cells migrated to the injured brain regions, and turned into neurons that produced dopamine. ‘The cells not only increased dopamine but also provided neuro growth factors that helped recover whatever is left in the brain and reduced inflammation,’ said Ruslan Semechkin, the ISCC’s chief scientific officer, who plans on human trials soon.

A dose of stem cells delivered to just the right sweet spot could mend the fractured neural circuits that ferry signals throughout the brain, holding promise for relief of psychiatric diseases from bipolar disorder to schizophrenia. The technology might one day ease learning disabilities, including deficits in information processing and attention. But the application closest at hand is the one that could rescue the boomer generation, my friends, and me, from the looming loss of our memories, our social skills, and our very selves. One day soon, neural stem cells will be used like brick and mortar to shore up the crumbling walls in our brains and restore lost functions so we’re almost good as new. ‘We can change the face of therapeutics with neural stem cells,’ says Eva Feldman, a neurologist at the University of Michigan who is a leading stem cell researcher. ‘They’re like chicken soup for the brain.’

I think about this when I go through an old family album from my childhood and come upon photos of two people I had never met – my parents as newlyweds, with me aged seven months between them, when they were young, in love and full of dreams, before the marriage of two wildly mismatched people was curdled by endless arguments and bitter disappointments.

It was the Roaring Twenties. My father’s life, like that of the nation, brimmed with promise

It was not long after the Second World War. My mother, Marie – who had been a model for more than a decade in New York City’s garment district – looked very stylish in a 1940s kind of way, in a tailored blazer with shoulder pads, with raven hair that gleamed in the sunlight, owl-shaped sunglasses and full, ruby‑red lips that made her resemble the then‑popular actress Linda Darnell, my namesake. My dad, looking tweedy in a wool sports jacket and sweater vest, is beaming with pride. In one snapshot, he was gazing at me with an expression I never remember seeing on his face, that of unalloyed joy.

Looking through the pictures, I think about what a blessing it would have been if, in his final moments, he could have somehow retrieved the shard of memory that contained one incandescent moment when his life’s upward trajectory seemed assured. It was a story he had often told me, about an event that took place two months before his 18th birthday, in April 1928, when his high‑school swim team battled another, DeWitt Clinton’s, for the New York City championship.

It was the height of the gin-soaked jazz age, the Roaring Twenties when the nation was in the heady throes of a long economic boom. People were making fortunes overnight in the stock market, and even shoe‑shine boys on the street offered up stock tips to their steady customers. My father’s life, like that of the nation, brimmed with promise.

Earlier in the year, he had come in second on the English Regents, a statewide exam taken by all high school seniors in New York, behind his classmate at George Washington High School, James Hagerty, who would go on to become press secretary to President Dwight Eisenhower. My father had been accepted on a scholarship to Cornell University in an era when most Americans barely finished grade school.

Hard‑working and enterprising, he was of medium height, with clear blue eyes that sparkled with bemused mischief, dark‑blond wavy hair that he combed straight back, and the lithe body of a swimmer in the days before athletes artificially bulked up with weights and steroids. A backstroker, he won his race handily. But it was a close contest, and the championship hinged upon the outcome of the final relay.

When my father climbed out of the pool after completing the critical third leg of the relay, the noise from the crowd was deafening. The final swimmer plunged into the water a split second after my father touched the end of the pool, and was a quarter of a length ahead of the DeWitt Clinton man. Still dripping wet and breathless from exertion, my father stood at the edge of the pool and cheered on his teammate as he sliced through the water, widening his lead at the finish by half a pool length.

At that moment, my father was exultant. Their victory seemed like an omen, and as he prepared to leave for college the road that lay ahead seemed infinite. ‘I was hoarse for days afterwards,’ he later told me. ‘But I didn’t care. We were the New York City champs.’