Pain is your body’s alarm system. It’s a sensation designed to tell you that something’s gone wrong. But being in pain, says Colin Klein, a philosopher at the Australian National University, is a bit like having your house guarded by a hyperactive terrier. Sometimes it barks at trespassers, but other times it gets upset at the postman. Sometimes it goes wild over nothing at all, and, on occasion, it would probably let in burglars if they brought snacks. Pain is correlated with tissue damage (the stuff you need protecting from), but the two don’t necessarily go together. If you’ve ever cut yourself and didn’t feel the slightest twinge until you saw blood, you’ve had tissue damage without pain. If you’ve ever felt a sting in anticipation of an injection or a dentist’s drill, you’ve had pain without tissue damage.

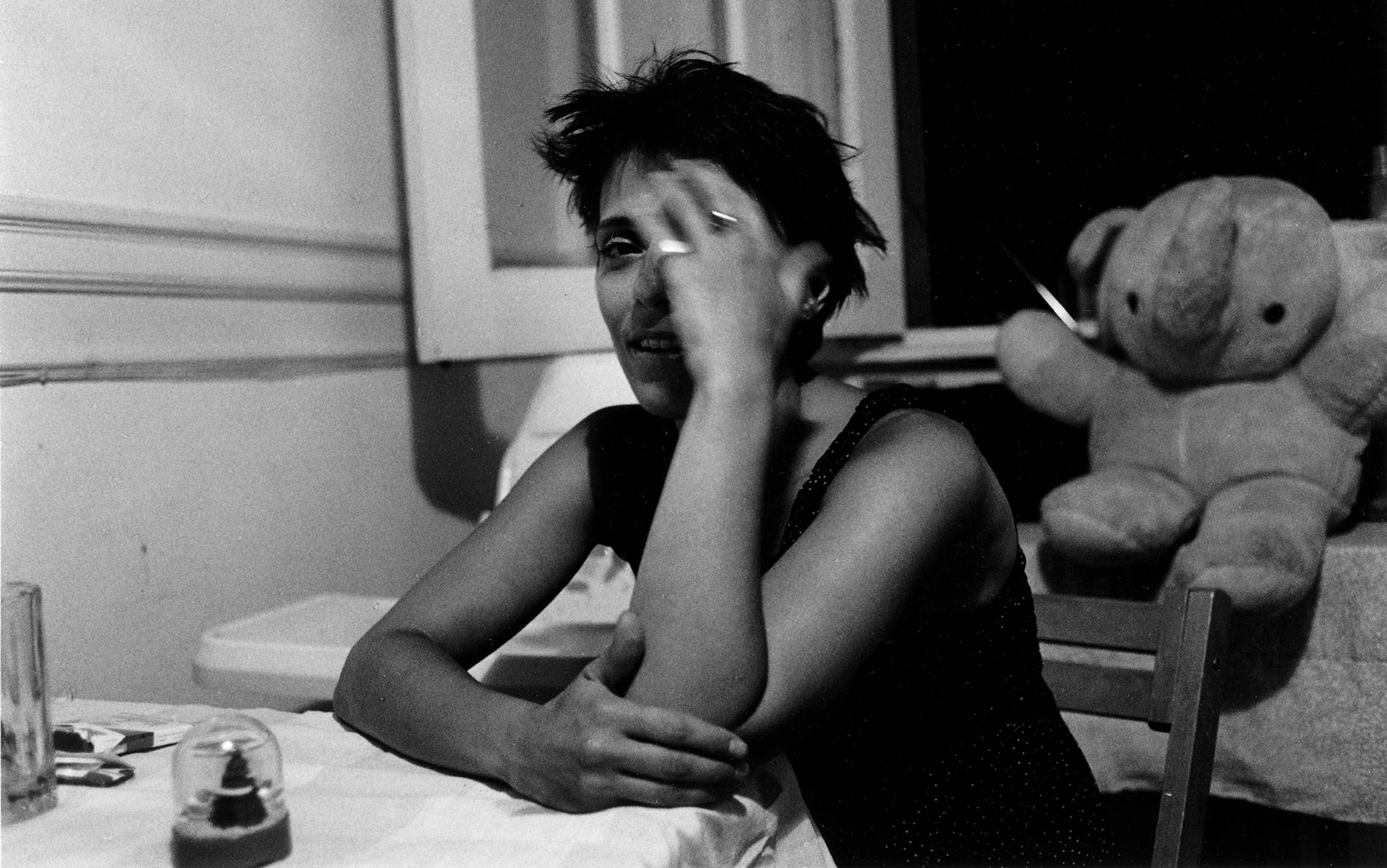

Part of what makes pain an effective protection mechanism also makes it inherently subjective. The International Association for the Study of Pain describes it as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience’. You wouldn’t jerk your hand back so quickly from a hot stove if pain was just a vaguely irritating tickle. Pain can protect us because we typically dislike it and find it emotionally distressing.

This affective dimension of pain – which we might also call its ‘interpretive’ or ‘psychological’ character – becomes especially complex when it intersects with gender. There’s good evidence that the modern Western medical system treats men and women’s pain quite differently. Women are more likely to have their pain dismissed or under-treated, often from a very young age. That’s especially true for women of colour, whose pain receives significantly less treatment than that of their white peers. Clinicians investigate women’s chest pain less frequently than men’s – even when women have all the classic symptoms of a heart attack, and even though heart disease is the leading cause of death in women. Women are also far more likely than men to have a physical illness misdiagnosed as a psychiatric condition, particularly depression.

One reason for these problems is that we don’t listen carefully when women talk about their lives and experiences. Women are often subject to what the philosopher Miranda Fricker at the City University of New York has called a credibility deficit: they’re treated as less reliable sources of information, precisely because stereotypes cast women as untrustworthy and irrational. As a result, society’s understanding of things such as workplace harassment, sexual violence and intimate partner violence is profoundly skewed, since we’re less likely to believe reports from the people most likely to be affected.

This credibility deficit makes women’s descriptions of their own lives a feminist issue. Feminists are more than justified in urging us to #BelieveWomen, as the Twitter hashtag puts it. Pain, though, is a particularly interesting case, because it reveals the limitations of this simple and compelling call. The demand that we recognise women’s pain is justified and necessary. But the way this demand plays out risks inadvertently reinforcing a deep-seated social bias about the hierarchy of psychological versus physical suffering – and doing so in a way that hurts women once again.

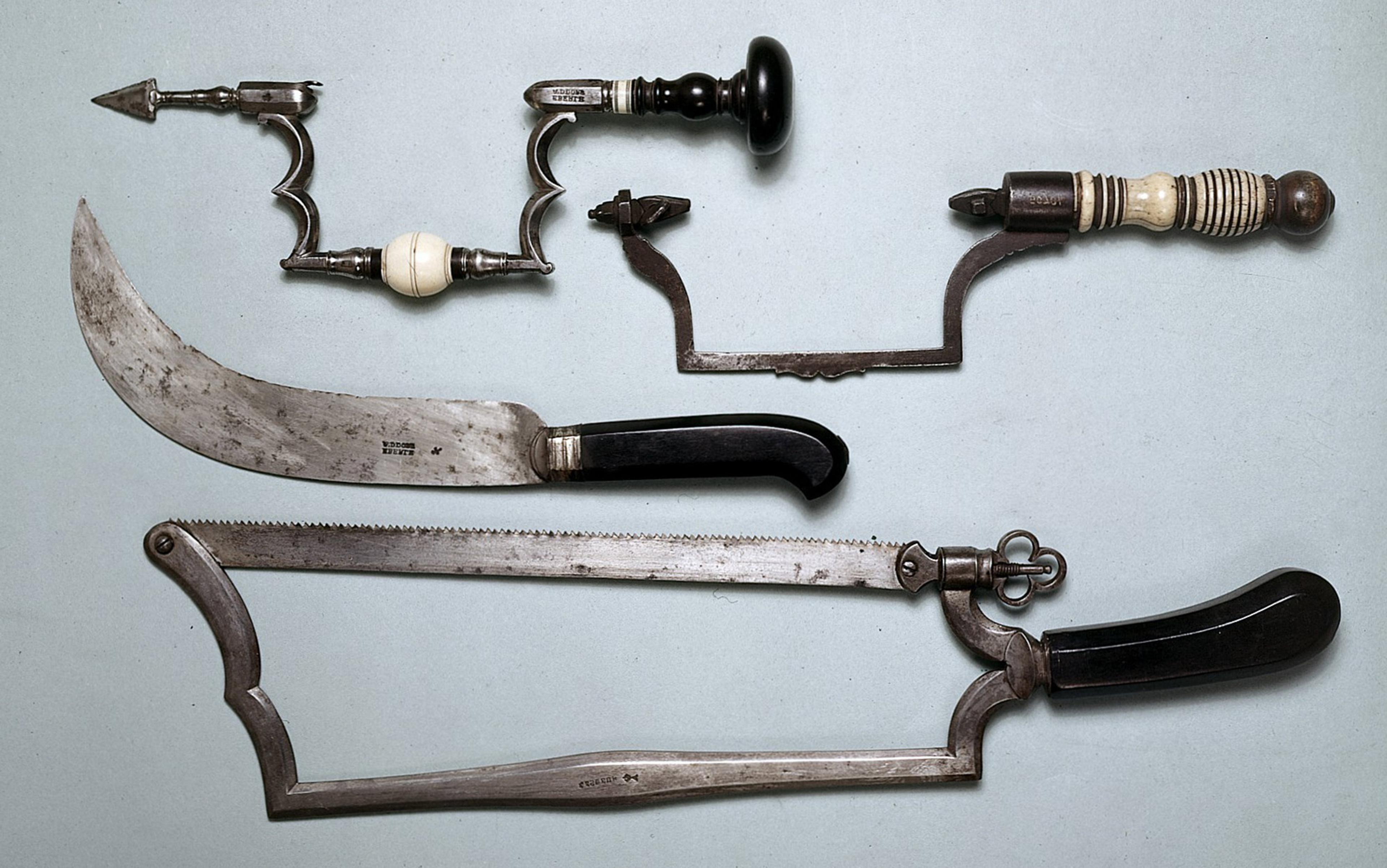

In 1949, The Journal of Clinical Investigation published a landmark study on pain in childbirth. The question was simple: do women actually experience pain in childbirth, or are they merely reacting hysterically to a stressful situation? The study’s authors, the obstetricians James Hardy and Carl Javert at Cornell University in New York, wrote:

It is a common observation that patients differ widely in their reaction to childbirth, some women giving evidence of great distress and others maintaining a high degree of equanimity throughout labour. These observations have led obstetricians to question the existence of pain in certain patients.

Reassuringly, they concluded – using pain measurements normalised on male subjects – that childbirth is painful.

By the 1970s – the heyday of the ‘natural childbirth’ movement – scientists broadly agreed that women do experience pain in labour. But there was still controversy as to why. Some researchers suggested that how much pain a woman felt was influenced primarily by factors such as her closeness with her husband and his role in the delivery process, as well as her emotional stability during pregnancy. Women were assured that little or no pain should be possible – in fact, birth should be positively enjoyable – if only they could just calm down.

Women’s pain, it seems, is hysterical until proven otherwise

The cottage industry of blaming women’s emotions for their pain hasn’t gone away in the intervening decades. A large body of current scientific research considers whether women’s emotions are a primary cause of good or bad outcomes in the treatment of breast cancer, including pain during and after treatment. Now, there’s nothing particularly pernicious about asking how psychological factors might affect treatment outcomes. The problem is not that we’re interested in the psychological dimensions of breast cancer pain, but that we’re so much more interested in the psychology of breast cancer than in the psychology of testicular cancer or liver cancer. In just the same way, in the 1970s, we were interested in ‘natural’ childbirth but not interested in ‘natural’ kidney stone passage – or in researching the extent to which men’s emotional stability or closeness with their wives mediated their kidney stone pain. Society seems so much more concerned with the role of emotions when women’s health – and women’s pain – is at issue.

Alternatively, consider the fact that a woman who finds sex painful (without an underlying physical pathology that makes sex painful) currently meets the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder if the pain causes her distress. The definition considers only her pain and the distress it causes her – even if she’s having sex in a world that prioritises men’s sexual pleasure over women’s discomfort, or having sex with a partner who expects rough and aggressive intercourse. If it hurts and that bothers her, she technically meets the criteria for a mental disorder. Women’s pain, it seems, is hysterical until proven otherwise.

Against this backdrop, there are now growing calls to trust women’s reports of pain – to #BelieveWomen, to trust that their pain is real. Of course, women’s pain is real. But here’s where a subtle shift occurs: the defence of women’s pain often becomes an argument that such pain isn’t psychological in origin. For pain to be real – to be legitimate, to be truly painful – it must have an organic physical basis. And that’s where things get messy.

When women get a physical illness, they’re more likely to be overly psychologised. What complicates the picture is that evidence suggests that women are also more likely than men to suffer from pain because of a psychological illness. For starters, women seem to experience both depression and anxiety at higher rates than men. Such findings must be handled with care, since it’s not clear how much of this difference is due to diagnostic bias – that is, both the tools that we have for measuring depression and anxiety, and the biases of mental health professionals, might skew toward over-representation in women and under-representation in men. But given everything we know about women’s lives – the abuse, the violence, the barriers, the burdens of caregiving – it’s plausible that women would struggle with depression and anxiety at higher rates. We can believe that women suffer from mental illness more often without needing to believe they’re inherently emotionally fragile.

There’s also evidence that women and men experience psychological illnesses differently. When men are depressed, they’re much more likely to experience anhedonia and substance abuse, while women are more likely to report physical symptoms such as fatigue and, yes, pain. Moreover, many of the most strikingly embodied psychiatric illnesses – anorexia, bulimia, non-suicidal self-harm, conversion disorder, factitious disorder – are far more common in women than in men. Again, some of the disparity here might be due to cultural bias. Would the ardent devotee of ‘extreme intermittent fasting’ be diagnosed with an eating disorder if he were a 16-year-old girl who wanted to be thin, instead of a 35-year-old tech bro who wanted to master ‘biohacking’? Quite possibly. And yes, some of the gender disparity in diagnoses such as conversion disorder might include women who have received a psychiatric label for what is in fact a physical illness. There is precedent for this. Multiple sclerosis disproportionately affects women, but was originally considered to be a male-dominated disease, partly because women were often misdiagnosed with ‘hysteria’. But these qualms aside, we do have solid evidence that psychiatric illness can dramatically impact the body, and that its patterns of embodiment are different for women than for men.

Gender, psychiatric illness and the body are clearly entangled. Likewise, the more we learn about pain, the more we understand that it’s an incredibly complex biopsychosocial phenomenon. It’s not just a simple, reactive sensation. In many cases of long-term chronic pain, for example, the initial pain response is caused by an injury, but the pain persists long after the damaged tissues have healed, because the body still perceives itself to be vulnerable. Pain protects us – but it’s better understood as a warning sign that your body believes itself to be in danger, rather than a direct perception of physiological damage.

What produces your pain might not affect how it feels, but does affect how to treat it

Whatever the experience of pain, there are always both psychological and physiological components. If you cut your finger, the pain you feel has an organic physical cause. But you’ll also experience the pain as unpleasant. Likewise, if you have a headache because you’re stressed, you’ll probably also experience things such as muscle tension, elevated heart rate and raised blood pressure. No one’s pain is ever ‘all in their head’, and no one’s pain is ever ‘purely physical’ – except insofar as we are all physical organisms and everything that happens to us, physical or mental, is realised in our bodies.

Our best current understanding of pain thus suggests that there isn’t really a difference between ‘psychogenic’ pain and ‘physical’ pain. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t distinguish between pain for which the primary causes are physical pathology, and pain for which the primary causes are psychological distress. What produces your pain might not affect how the pain feels, but it does affect how to treat it. If you have chest pain because of heart disease, doctors really need to treat your heart. If you’re experiencing chest pain because of stress, doctors really need to address your anxiety. In plenty of cases, though, the primary causal factors might be both physical and psychological – your back might be hurting both because you’re stressed and because long-term pain has caused you to develop painful movement patterns or muscle imbalances. So, to get on top of your pain, you need to tackle both at the same time.

Of course, understanding that your headache is primarily due to stress doesn’t make the pain any less real, or any less painful. Pain is pain, whether its cause is primarily physical (an injury, a nerve problem) or primarily psychological (stress, depression). In much the same way, depression feels like depression whether it’s caused by complex socioeconomic factors or by low thyroid. The causal origin doesn’t determine how it feels, even if it’s important for understanding how best to treat it.

This is not to say that context doesn’t matter – far from it. In the last year of her life, my dearly departed border collie, Willow, had advanced arthritis in her hips. She was clearly in pain much of the time. She would move stiffly, lay down gingerly, and struggle to get up and down stairs. But when Willow was outside with her frisbee, she transformed. She would run, bark, race after the frisbee with delight. The limping gait wouldn’t come back until the frisbee disappeared.

Was she faking it? Was her pain all in her head, or not caused by her arthritis? Did we need to send her to a doggie psychiatrist? Obviously not. Rather, Willow’s experience of pain, and her reactions to it, were affected by more than just the state of her hip joints. When she was at her happiest and most distracted, she seemed to hurt the least – or at least, the pain didn’t bother her as much.

Let’s say – as I hope is true – that many of us now earnestly want to #BelieveWomen when they say they’re in pain. It’s often unclear, though, just what this means. Perhaps the claim is simply that we should believe women when they say they’re suffering. That seems obviously true: no one has more insight into whether and how much pain you are experiencing than you do. Of course, women are still capable of lies and distortions. Believing women is not the same as treating them like magic oracles. The thought, rather, is that we shouldn’t impugn their credibility simply because they are women. And we often do find women less credible – we think they’re exaggerating or being dramatic – when they tell us about their pain.

However, calls to believe women often become something stronger: a claim that we should believe women’s pain is caused by a physical disease, at least when they insist or until we can show otherwise. In this way, even feminist activists can fall into the trap of implying that ‘real’ or ‘serious’ pain can’t be psychological in origin. The demand to believe women is rooted in the idea that they’re in the best position to talk about what’s happened to them, that they have a special kind of authority and insight. But while you can have first-person authority about whether you’re in pain (no one is in a better position to know than you), you don’t have privileged authority about why you are in pain. You might have relevant insights – if the doctor is saying your chest pain is due to anxiety and you don’t feel anxious, you can be justifiably skeptical. But if you insist that your pain is caused by your knee, when your doctor is sure that your knee is fine and says the pain is referred from your hip, first-person privilege doesn’t seem to apply.

Often, we downplay what women tell us about their lives precisely because we view women as unreliable and flighty. Likewise, women are much more likely than men to have their pain dismissed as ‘all in their head’. But these are not the only stigmas at work. We also stigmatise anything psychological as somehow less serious, less real or less worthy of our concern – especially when it comes to women.

Mentioning psychological factors seems to create a kind of gestalt shift when women are under consideration

The situation leads to what I call a stigma double-bind, produced by two separate axes of bias: ‘women are hysterical’ and ‘psychiatric illness isn’t real’. It borders on impossible to combat one area of stigma without inadvertently reinforcing the other. Women who have suffered needlessly from psychiatric misdiagnosis object, quite justifiably, to the over-psychologising of their pain. But the more we insist on centring the physical, the more we sideline the ways in which depression, stress and trauma can cause and influence pain. And that’s absurd. Pain is a threat response, and the brain employs almost identical machinery regardless of whether a person is harmed socially or physically.

This is where the double-bind becomes especially difficult. To acknowledge the psychological aspects of pain, we have to emphasise the role of stress and emotion. But the very mention of stress or emotion seems to do dramatic things to how women in pain are perceived. In one fascinating study, doctors were given identical case descriptions for two hypothetical patients – a 48-year-old man and a 58-year-old woman – with the same objective probability of a heart attack. In the first case, the patients were described as having chest pain, shortness of breath and an irregular heartbeat. The majority of doctors suggested a heart attack diagnosis for both. In the second case, the patients were described with the same physical symptoms, but they were also described as experiencing stress. Stress raises the likelihood of a heart attack, regardless of gender. But while the majority of doctors still suggested heart attack for the male patient, a mere 17 per cent suggested it for the female patient (and only 30 per cent suggested cardiology referral, compared with 81 per cent for the male patient). Mentioning psychological factors seems to create a kind of gestalt shift when women are under consideration. Once we start talking about women’s emotions, it’s hard not to summon the spectre of hysteria.

One problem is that it’s so easy to move from what is in fact true of women to what is somehow inherently true of women. When we say: ‘Women suffer from higher rates of depression and anxiety,’ that’s a true generalisation that might be explained by contingent socioeconomic factors. And it’s a true generalisation that might tell you nothing whatsoever about the particular woman sitting in front of you. But people too easily infer that women in general, by virtue of being women, are inherently depressive and anxious. And so, unsurprisingly, when we emphasise the psychological factors that affect pain – everyone’s pain, because that’s just how pain works – this tends to disproportionately affect women.

Stigma double-binds are pernicious because they’re so hard to circumvent. It’s important not to ignore the very real extent to which stress, depression and trauma affect women’s pain. Yet it’s equally important not to reinforce the idea that women’s problems can be blamed on their emotions. It’s incredibly difficult to do both those things at once, and there are significant harms to over-correcting in either direction. Treating women’s physical illnesses as psychological distress can put their health and lives at risk. But denying women mental health services causes harm too, as does subjecting them to needless medical tests and treatments.

I suspect there’s no easy way out of such an entangled net of stigma. But if part of any solution is admitting you have a problem, then perhaps what’s needed is simple acknowledgement of the existence of stigma double-binds. It would be nice if we could just do what Twitter asks of us – to #BelieveWomen and move on. The less hashtag-friendly epistemic work is much harder.