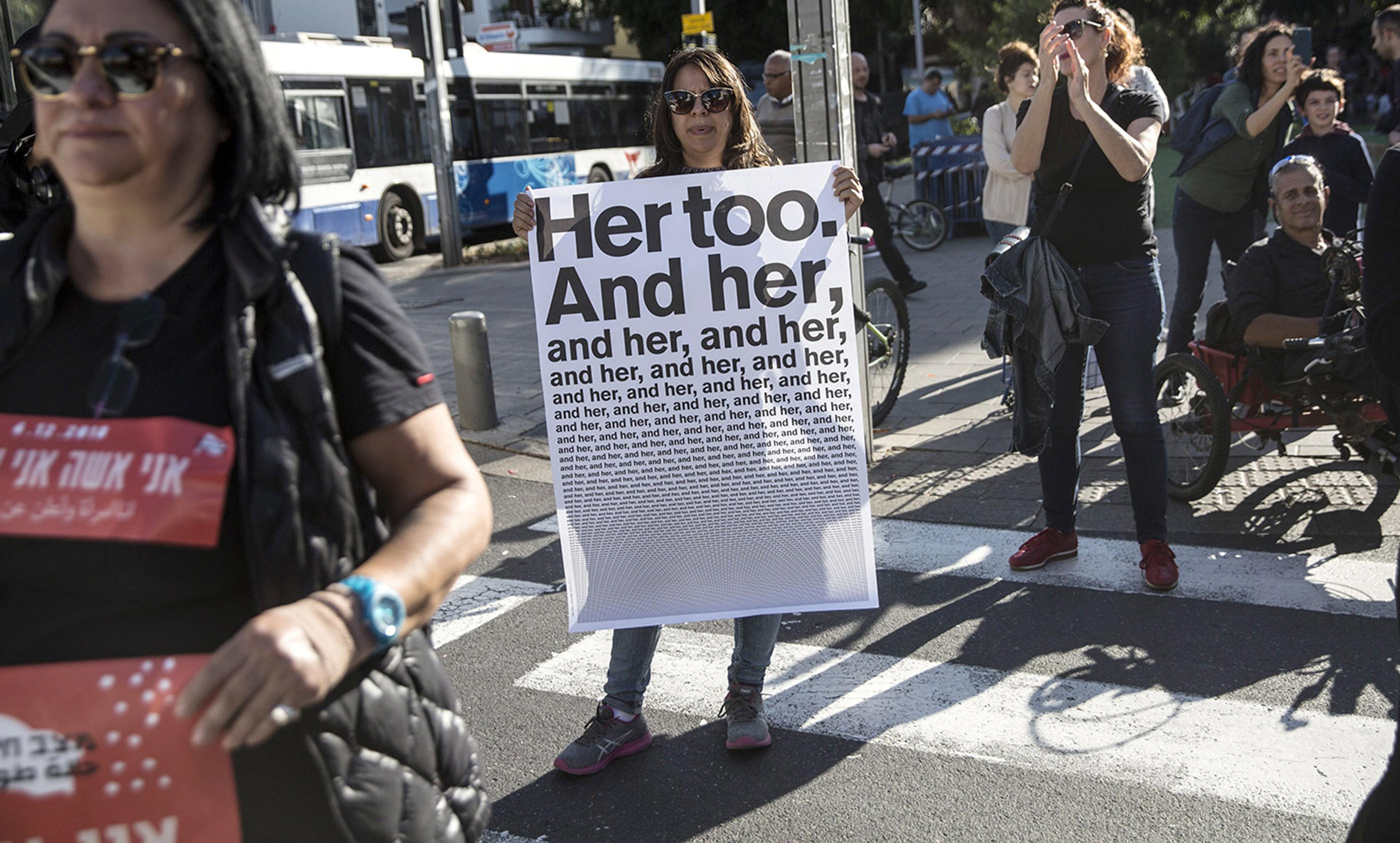

Gabriel Saldana/Flickr

Activists at universities and beyond are increasingly using so-called ‘No-Platform’ arguments to ban the public speech of those whose views they find offensive. In practice, this typically involves staging protests or petitioning university authorities to disinvite ‘offensive’ individuals from speaking engagements. Examples abound from both sides of the Atlantic: in the United States, students have No-Platformed the likes of Condoleezza Rice, Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Christine Lagarde, while in the United Kingdom their targets have included Maryam Namazie and Germaine Greer, among others.

At times, No-Platforming is also used to silence speech about certain topics, as with the cancelled student debate on abortion at Oxford. In all these cases from the past year or so, the justification for No-Platforming is more or less the same: that allowing the person in question to speak would cause some kind of ‘harm’ – not physical harm, but psychological, emotional or social damage – to an individual, group, or even society at large. Indeed, No-Platforming is primarily a tool of identity politics activists who seek to protect minority groups that feel threatened or marginalised by the existing social order. In essence, then, the goal of No-Platforming is greater social justice, realised through the equalisation of power relations. The means to this end is pre-emptive censorship of speech in certain contexts.

Those who challenge No-Platforming are often interpreted uncharitably by its advocates, and are accused of failing to acknowledge the real harm or offence that speech can cause, particularly to marginalised groups. Let me make, therefore, a disclaimer that I hope deflects this move. I am not advocating an ‘anything goes’ approach to free speech. This is an untenable position, as the rightful bans on child pornography, perjury, extortion and much else illustrate. I acknowledge that speech can cause real harm, and that it should be limited in those rare cases in which it does. I even agree that No-Platforming might sometimes be an appropriate means of pre-empting such harm, for example in cases of probable incitement to violence or psychological trauma. However, I wish to raise questions about the nature of the harm that can legitimately justify restrictions on speech, and the way in which it is discovered.

Contemporary advocates of No-Platforming have so far failed to provide any convincing, rigorous definition of ‘harm’ to justify their practice. Typically, they claim that offensive speech undermines the ‘personhood’ of those it targets. However, in the vast majority of cases, they fail to demonstrate how this alleged violation occurs, nor even what they mean by ‘personhood’. The intellectual foundations of No-Platforming are thus very shaky. There are two reasons for this. First, justifications for No-Platforming fail to separate cases of genuine harm from those of trivial offence or discomfort. Second, in failing to make that distinction, No-Platforming hinders the progress of social justice.

When the No-Platform principle emerged in the 1970s, it was explicitly restricted to racist or fascist speech, with ‘harm’ clearly defined as incitement to racial hatred or to violence. The problem with today’s No-Platform movement is a lack of precision about what is meant by ‘harm’. Instead, No-Platformers tender a wide range of reasons for their practice, including feeling uncomfortable, threatened, unsafe or offended. These complaints do not constitute harm in the same tangible or objective way as, for instance, incitement to violence. Rather, they are claims of purely subjective experience.

This premise is central to the contemporary politics of identity. Subjective experience, the argument goes, is by definition exclusive: it is unknowable to those who do not have the relevant identity characteristic. The subjective experience of womanhood, for example, is unknowable to any man; that of being black is unknowable to anyone white; that of being transgender is unknowable to anyone cis. Accordingly, the subjective harm claimed by a particular identity group cannot be questioned by any other. To put it differently, if one member feels harmed by some speech, then they have been harmed ipso facto. By this logic, all claims of subjective experience must be considered equally valid.

It is easy to see how readily this position becomes exploitable. If No-Platforming can be justified exclusively on the basis of a given group’s subjective experience, we cannot ensure that petty cases – based on minor discomfort or even mere disagreement with some speech, yet cloaked in the language of offence or harm – are dismissed. In other words, we have no way of adjudicating between requests for No-Platform when we lack an objective measure for determining which requests ought to be upheld, and which ought not.

To understand the practical consequences of this problem, it is useful to consider the phenomenon that Eugene Volokh, law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, calls ‘censorship envy’. An initial request by a given identity group to censor some speech on the basis of claimed harm prompts analogous requests from other identity groups. No-Platforming becomes contagious. Consistency requires that once we allow some speech bans due to claimed harm, we cannot justifiably deny other requests made on the same grounds, since, given the unknowability of others’ subjective experience, all claims of harm must be treated as equal. And inevitably, at some point, these claims come into conflict.

The ongoing controversy surrounding the British writer Julie Bindel, for instance, exemplifies this problem. Bindel is a trans-exclusionary feminist, and has been No-Platformed by the UK’s National Union of Students on grounds of alleged transphobia. But how can this decision be reconciled with the equally valid claim of trans-exclusionary feminists that womanhood is contingent upon being biologically female? These feminists can likewise, legitimately, request to No-Platform trans-inclusive viewpoints. The upshot is that no one at all gets to speak about the issue. This leaves us at a stalemate: the logical consequence is emphatic silence on nearly every issue that bears upon identity.

In a pluralistic society, justice requires that we balance the competing interests of different groups in the fairest way possible. We need to be able to communicate what we believe, so that we can persuade others that our interests should be acted upon collectively. To the extent that No-Platforming forcibly subordinates the interests of society to one group’s subjective interest, without providing any way to determine whether that subordination is in fact just, No-Platforming is fundamentally at odds with social justice. Its claim to be a moral form of censorship is baseless and a smokescreen. To be legitimate, any No-Platform principle should be founded upon a consensual and objective understanding of the kind of harm that justifies curtailment of speech. Wide-ranging freedom of expression is too important both to education and to democracy to be restricted in the name of an activism based on subjective perceptions of harm.