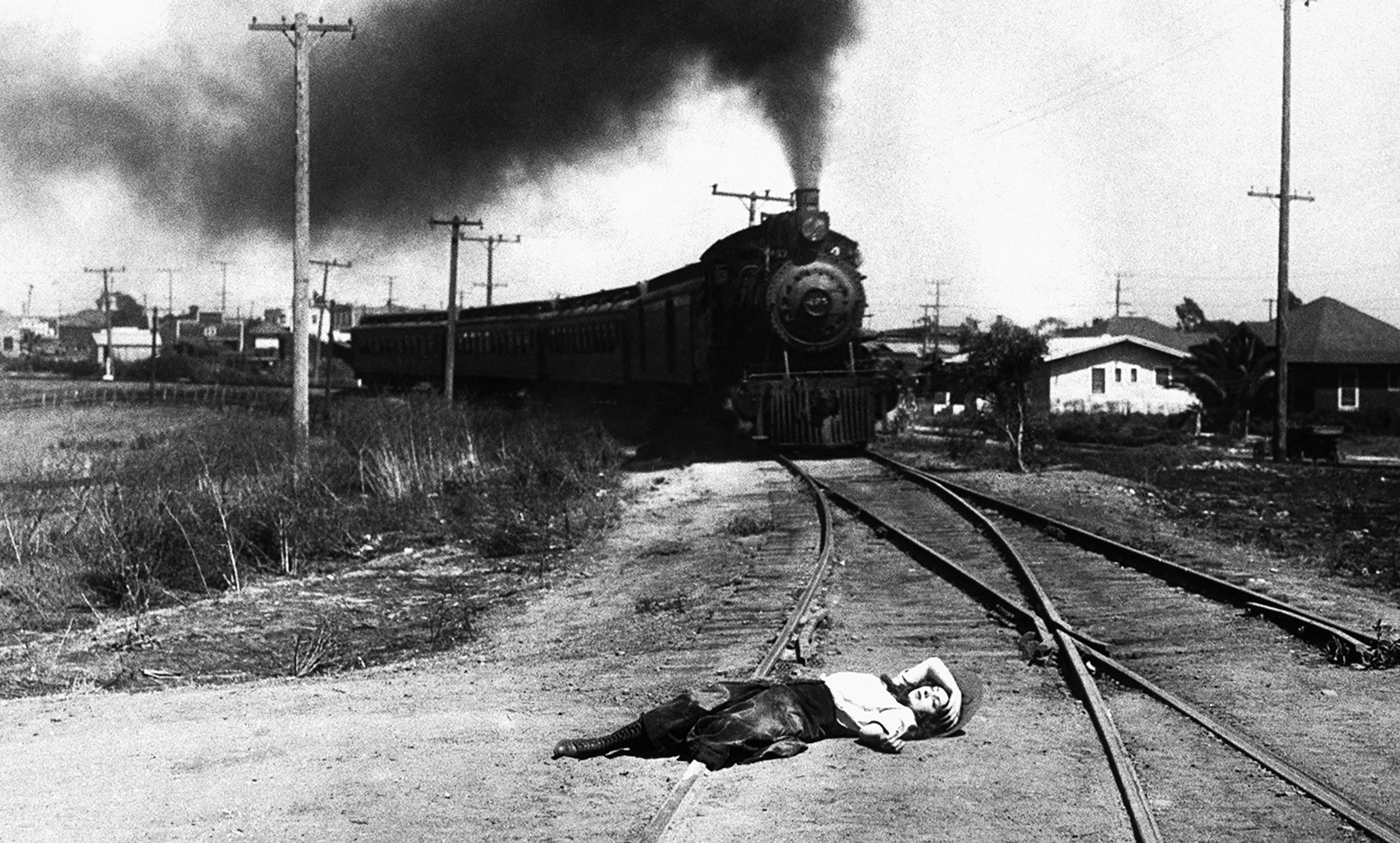

Photo by Bettmann/Getty

People have concerns about the psychological effects of endlessly playing shoot-em-up video games but I sometimes wonder whether doing moral philosophy is just as corrosive. A worryingly large proportion of ethical thought experiments involve fantasies of homicide, requiring you to play God and decide who gets tortured or killed, with no option for everyone to get into a group hug or have a nice cup of tea.

Here are just a handful: would it be right to torture someone in order to extract information to prevent a bomb going off, killing thousands? Is it justifiable to hang an innocent man to calm a mob who would otherwise run riot and kill many more? Should a parent take a lifeboat to a raft with five children clinging to it or to another with just their own child, knowing there is not enough time or fuel to do both? Should a doctor let a patient die, knowing that the patient’s organs can then be transplanted to save five other people? Should you divert a runaway train from a tunnel where it would crush five people into another tunnel housing just one unfortunate person? Or should you stop the train by pushing someone in front of it?

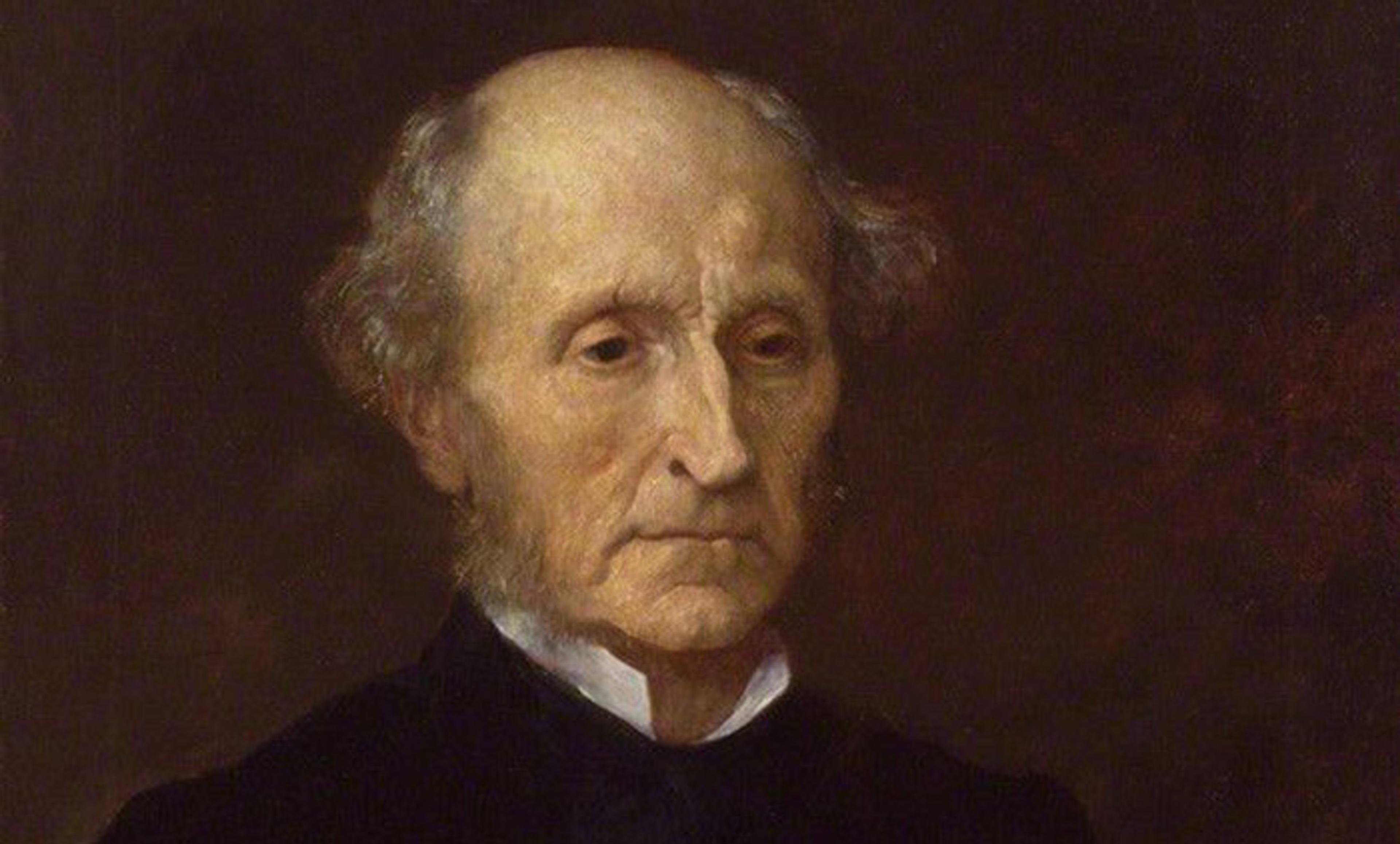

Responses to such thought experiments are meant to expose the extent to which we think moral judgments should be made on grounds of duty and principle, or on utilitarian calculations about whether actions increase or decrease wellbeing. But interestingly, no matter what people’s ethical framework, the scenarios seem to most people to be genuine dilemmas. Those who take utilitarian options will usually be uneasy with the cold, callous, calculating nature of the judgement; while those who refuse often worry that trying to keep their hands clean only leaves more blood on them.

You could explain this unease in purely psychological terms. Indeed, there is good evidence that psychology plays a major role in how we think about such problems. Generally speaking, we are more likely to make utilitarian choices where there is some distance between our imagined action and those who suffer as a consequence. But when we are up, close and personal with the victims, we tend to back off. The same distinction appears in real life: people have fewer scruples about killing others remotely with drones than in shooting them while looking into the whites of their eyes.

Although psychology surely does play a part, I don’t think it’s the whole story. What these thought experiments also bring to light is that, in one way, we value life above all else, and, in another, there are things that matter even more than life.

Life is, in a sense, of supreme value because without life there can be no value at all. That’s why, if we are asked to make choices in which there is more or less life as a result, it seems wrong to choose less.

But what is it that makes life valuable? Not, it would seem, life itself. Most people think that there is no reason to prefer a permanent vegetative state to death. In many ways, the former is worse because it prolongs the agony for loved ones and takes resources away from others in need. Furthermore, despite some radical vegans’ claims to the contrary, most of us find it absurd to value the life of a hamster the same as that of a human.

If life has value, it is surely because of what life makes possible: love, aesthetic experience, great moments, creativity, laughter. But even these things are not judged to be unqualified goods. The context in which they appear matters too. The love between two psychopaths, egging each other to horrendous crimes, might seem good to them but is an abhorrent perversion to others. Nor do we value the laughter of tormentors or the building of great monuments with slave labour.

If we go back to those life-or-death thought experiments, in each case we can see that we are being asked to choose between saving more life at the cost of something that makes life valuable in the first place, or preserving more of what is of value at the cost of more life. When we allow innocents to die to save more people overall, we are sacrificing some of the dignity and respect we have for human life in order to keep more humans alive. When we torture to save life, we allow more cruelty into the world in order to keep more people in it. When we choose multiple strangers over one loved one, we reject the special bonds of love so that others can have a chance to maintain theirs.

That’s why I believe most such thought experiments are never satisfactorily solved. Indeed, I would suggest that the best way to use them is not to see them as puzzles to be solved at all. If we ever face such situations in real life, we will be forced to choose, and will have to do so based on the very particular circumstances of each case. The only general lesson we learn from these thought experiments is that there is sometimes a tragic conflict between life and what makes life valuable in the first place.