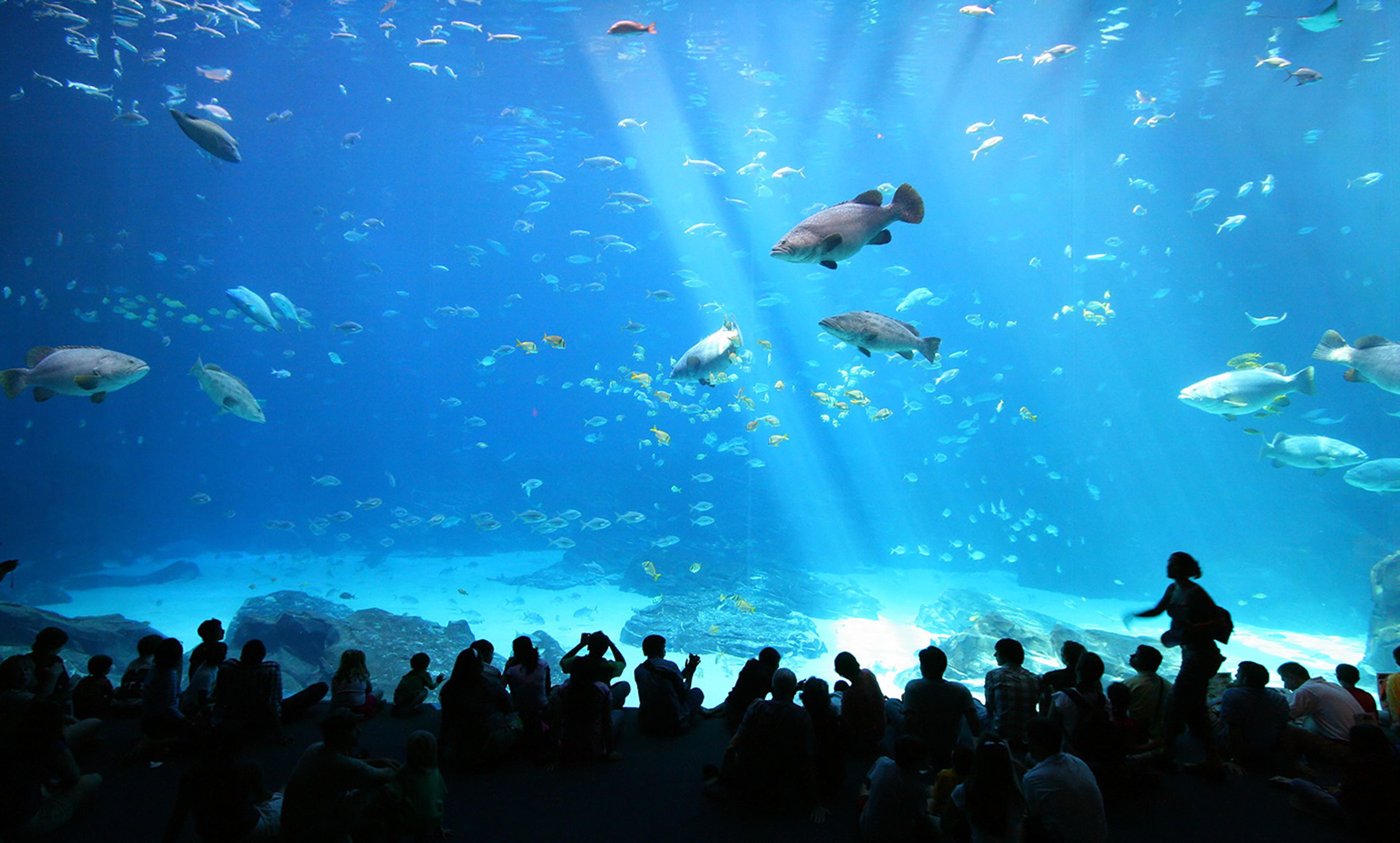

Girish/Flickr

What could possibly be wrong with taking your child to an aquarium? It seems like an innocent enough pleasure. Most children love watching exotic fish swimming behind glass, seahorses, sharks, rays, jellyfish and turtles. A visit to the aquarium is a mixture of entertainment and education, and seems much less morally dubious than going to a zoo to see gorillas, and probably much better than playing point-and-shoot video games.

True, recent publicity about the US theme park chain SeaWorld and the treatment of orcas makes it clear that some aquariums step over the line when it comes to the humane treatment of aquatic animals. While the argument has been won for orcas, the moral situation for other marine animals remains murky. New dolphinariums are opening around the world – dozens in China, but also in the United States, Thailand and Kazakhstan, with plans for more in Poland, Cyprus and Turkey – though not all dolphinariums put their animals to work.

But what’s the problem with an aquarium that concentrates on fish rather than marine mammals? Many of us were taken to such places as children and enjoyed the experience. Why not continue that practice?

Aquariums can, of course, be centres for conservation and research. But there is a special issue when we take children to visit them. We are setting an example of how we think we should live, and this might be done only by ignoring what’s in front of us, lying just beneath the surface.

By taking children to these places, we are communicating to them indirectly that it is acceptable to confine non-human animals to small tanks that dramatically restrict their movement, and derive pleasure from gawking at them. Fish, which would in the wild swim many miles a day, are typically confined and subjected to stress and shock from people tapping on the glass, injured from being mishandled and in encounters with tank-mates, or languish in poor health due to deficient diets, disease or cramped and unbalanced environments designed almost entirely with the enjoyment of ticket-holders rather than the welfare of the fish in mind. Last January, for example, a great white shark died after only three days in an aquarium in Japan; octopuses are famous for their resourceful escapes; and sand tiger sharks in US aquariums frequently develop spinal deformities.

It is clear that the hundreds of millions of people who visit aquariums annually don’t have a particular problem with any of this, and might well argue that it would be hypocritical to worry about confining a fish in a tank if they are happy to eat meat or farmed fish, or to keep goldfish or other pets at home. Yet if a trip to the aquarium is supposed to be educational, it’s unclear what can be learnt about how fish actually live in the wild from viewing them in such unnatural circumstances. A documentary film would be much better.

Still, given the alternatives, isn’t this a relatively harmless way of passing the time? Not really. Certainly, an aquarium is nothing like a bullfight: there is no deliberate cruelty involved, and a well-kept aquarium focuses on the welfare of the fish. Why single out aquariums for this sort of criticism? However, even if the animals are well-treated, there are further hidden issues we should care about.

A key question is where the animals come from. Most public aquarium stock is wild-caught. This is problematic not only because fish populations are already highly exploited – stocks are collapsing from overfishing, and the number of public aquariums are growing – but also because the live-capture industry is not well-regulated, and some of its practices are highly questionable. For example, hand-made bombs and sodium cyanide are still sometimes used to stun and capture fish; this kills many in the initial shock, weakens the survivors, and damages the surrounding habitat (see Bernd Brunner’s essay for Aeon). While net capture is better for the habitat, it’s still stressful for the animals, and the risk of injury is significant. More animals are caught than necessary because so few will survive the journey to the tanks.

The effects of this on remaining populations are poorly monitored. Fish in aquariums are rarely the ones that are threatened, and many are unsuitable for breeding in captivity. While some species can be bred ex situ, few aquariums supply a large enough gene pool, meaning that problems related to inbreeding, overbreeding, crossbreeding and creating genetically modified ‘Frankenstein’ fish are common. Fish sold in supermarkets is sometimes labelled ‘responsibly sourced’, but in public aquaria there is rarely any equivalent information about how the animals were obtained, perhaps because those who run such places either don’t know the sources of their animals, or would rather that we didn’t find out too much about that.

Ideally, we’d take our children to wild places to see aquatic animals swimming freely. But diving and snorkelling with fish is a luxury afforded to very few people. A good second best, however, is to watch documentaries or read books about marine animals. Going to an aquarium used to be one of the few ways to see marine life. But now that we have much better access to information via the internet, we should think very hard before taking a trip to the aquarium with our children – unless, perhaps, to teach them about the gap between appearance and reality.