For around 100 years, naturists – formerly known as nudists – have been arguing that public disrobing is physically and morally improving. They first promoted their ideas in illustrated books and magazines in the 1920s and ’30s, and soon extended their claims to the pleasures and practices of viewing nude bodies in photographs. They did this, in Britain, in the face of an incredulous public and a hostile legal system with strict ideas about decency and obscenity.

Can looking at nudes be good for you? The lively debates raised by historical nudists about the pleasures and powers of showing the nude body are fascinating. They provide surprising perspectives on questions about physical beauty, nature, and the sexualised body.

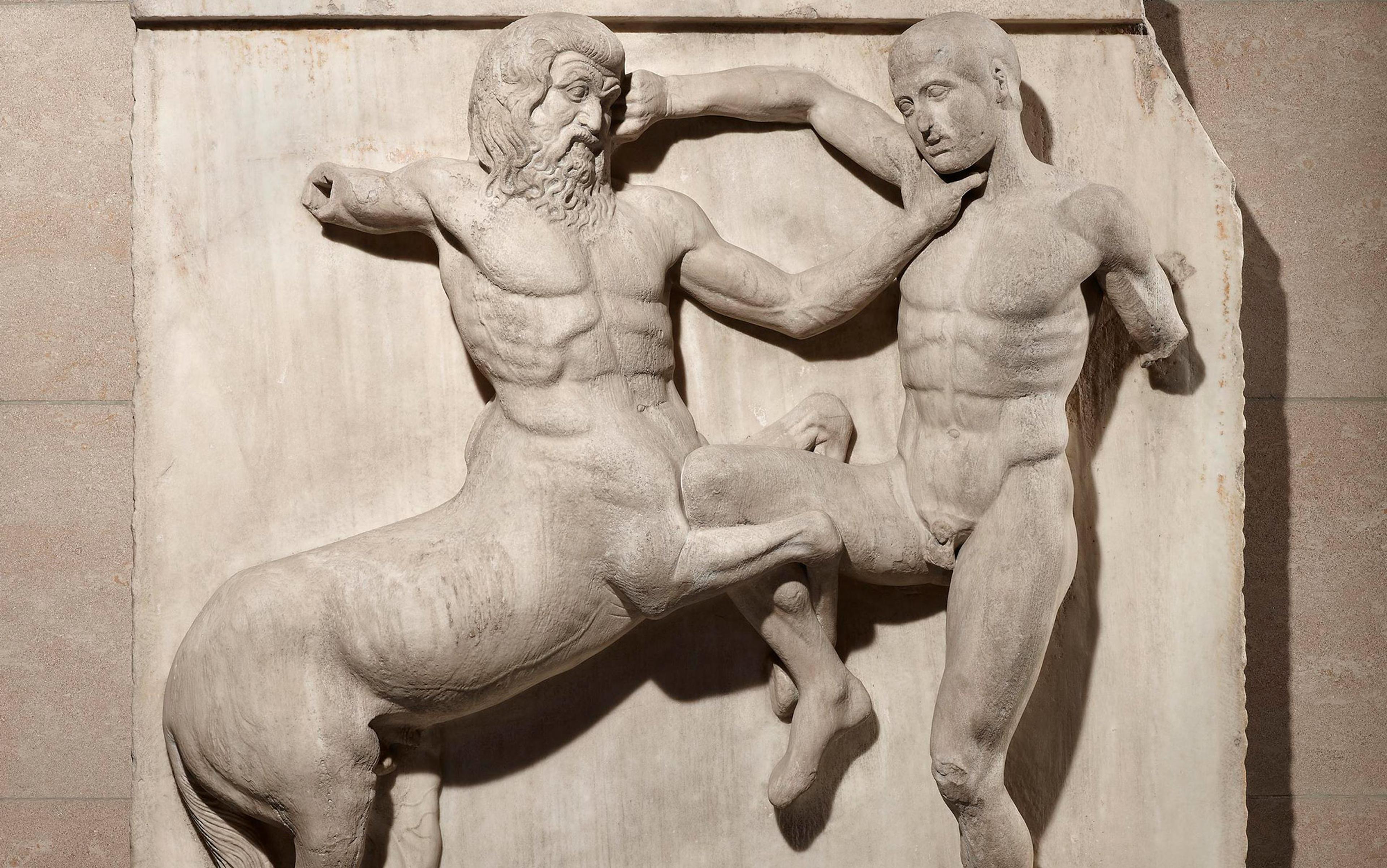

Although we are all born naked and the nude body is as old as humanity, social nudism as a distinct cause and as an organised community has late-19th-century German origins. Philosophers, artists and social reformers sought out anti-urban and anti-industrial alternatives as a way of promoting a more natural and authentic way of life. Their interests in natural health cures through exercise, diet and the purifying exposure of the body to the sun led to a cult of nakedness practised on plots of lands dedicated to group gymnastics and open-air swimming, and promoted through a body of zealous literature in the early years of the 20th century. Some of this thinking about health, youth and the triumphant body beautiful would later inform Nazi literature about national fitness and racial superiority.

International travellers from across Europe and the United States participated in German nudist practices before and after the First World War, and they enthusiastically wrote up their experiences for non-German-speaking audiences. The New York sociologist Maurice Parmelee was one US visitor who became a convert to the cause. His much-reprinted book Nudism in Modern Life: The New Gymnosophy (1929) developed a theory of nakedness for an Anglophone readership. He claimed that ‘gymnosophy’ – his preferred term, as an ancient Greek word combining nakedness and wisdom – ‘stands for simplicity, temperance and continence in every phase of life. It is useful in the rearing of the young,’ he claimed, ‘in the relations between the sexes, and in promoting a democratic and humane organisation of society. Consequently,’ he argued, ‘the implications of gymnosophy extend far beyond the practice of nudity alone, for it connotes a thoroughgoing change in the outlook upon and mode of life.’

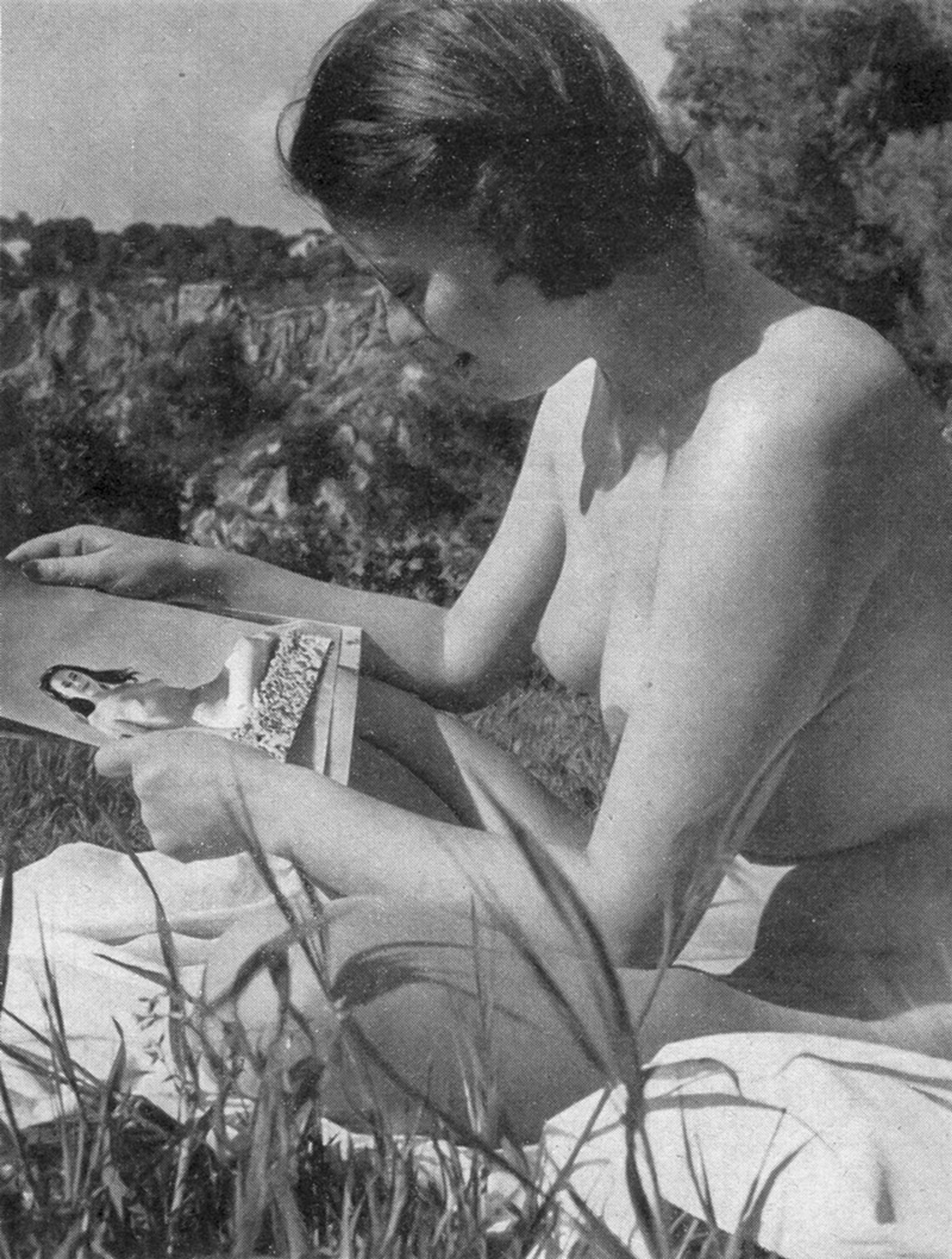

Last year’s hair style! by Ervin Marton, from The Naturist, January 1955. © Ervin Marton Estate

For Parmelee, and those who followed his line of thinking, nudism was libertarian, democratic and humanitarian. He claimed it would deliver a more egalitarian world, destroying class and caste systems, and establishing gender equality. Nudism, he asserted, ‘is a powerful aid to feminism, because it abolishes the artificial and unnecessary sex barrier and distinction of dress. The gymnosophic movement is,’ he believed, ‘the logical continuation and consummation of the woman’s movement, for it at last brings woman into the man’s world and man into the woman’s world, so that they can see each other as they really are.’ Parmelee’s study was illustrated with black-and-white photographs of naked white German youths assuming expressionist dance poses or boldly leaping for joy in the open air.

As the first tentative nudist clubs were established in Britain on a small scale in the mid-1920s, a home-grown promotional literature began to emerge. By the early 1930s, several nudist periodicals could be purchased cheaply from British newsstands, from the short-lived monthly Gymnos, which styled itself as ‘For Nudists Who Think’, to the longer-lasting quarterly Sun Bathing Review. Both were populated with high-brow articles written by physicians, psychiatrists and clergymen who detailed the physical, mental and spiritual messages of the movement.

Gymnos’s editors, like Parmelee, believed that nudism had the power to ‘unite all sects and denominations in one brotherhood’. To do this, and to maintain repute, public and social nudity needed to be divorced from any association with sex. To make this move, practitioners argued that nudism rejected ‘conventional modesty’ and produced an alternative system of ‘propriety, chastity and morality’. This was premised on ‘pure motives’ of ‘simplicity, beauty and truth’.

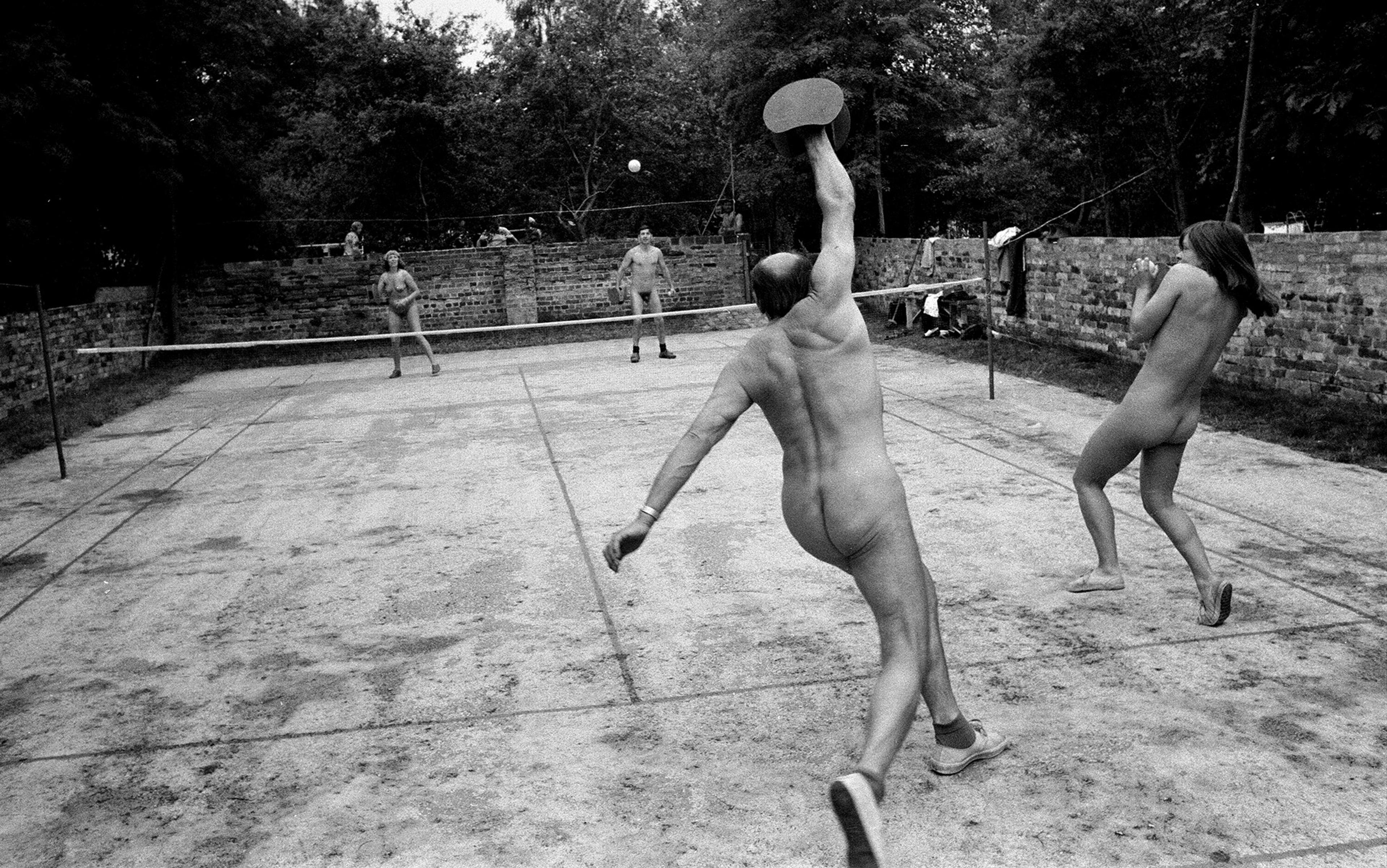

The psychological transformation that would come by seeing the naked bodies of others was a core tenet of early nudism. To show how this utopian world might look, British nudist magazines included nude photographs produced by professional photographers. Mostly taken in outdoor settings, these images sometimes documented practising nudists at camp, but more often showed idealised and heroic models in classical or painterly postures. Sun Bathing Review particularly promoted its status as ‘copiously illustrated’, which ensured it a readership of 50,000 by its second issue, far more than the quantities of practising nudists at the time. Bertram Park, a portraitist whose photo studio was frequented by the royal family as well as by nude dancers, was the magazine’s honorary art editor.

No 10 Nottingham Sun and Air Society campsite by A J Peacock Pochin, from the Sun Bathing Review, 1941. © A J Peacock Pochin

Park argued that ‘camera-consciousness’ on the part of the model was one of the biggest obstacles to the successful photograph. ‘Only rarely, as in so-called nudist colonies in England, and on the Continent, or at the Summer Schools of the Sun Bathing Societies, is complete unconsciousness of nudity achieved,’ he said. As a result, and owing to his claim that the dimensions of ‘the average middle-class girl are out of proportion as from the head to the hips’, he recommended statuesque professional models as photographic subjects rather than the mixed sizes and shapes of actual nudists. The persuasive power of the results, he argued, was important for ‘the moral and physical welfare of society’.

This modern Sunbathing Venus of to-day… from Health & Efficiency magazine, Christmas 1936. Courtesy of Hawk Editorial Ltd

While undoubtedly assisting with magazine sales among non-nudists who eagerly embraced the new opportunity to devour images of naked bodies, looking at nudes was argued to have improving effects on mind and body. Model bodies – always slim, white and young – offered templates to live by. They encouraged the unhealthy towards fitness, and held up an instructive mirror to non-model bodies. Early nudism, for all its egalitarian claims, was founded on eugenic principles about ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bodies, which led to discriminatory statements about those who did not live up to its ideals. Parmelee, for example, felt that those with fat stomachs should look and learn: ‘This unwieldy mass of flesh, sometimes containing folds and creases, and shaking jellylike with the motion of the body,’ he observed, ‘is one of the most unpleasant sights in gymnosophic circles.’ He argued that nudism ‘is the most effective measure for eliminating this monstrous distortion by spreading an ideal of human beauty and shaming those who fall so far short of it.’

‘The bodies of the other sex are no more attractive than carcasses in a butcher’s shop’

Nudism in its early days was also seen by its adherents as a sexual corrective. The sexologist Norman Haire argued that ‘so many of the sexual difficulties of our modern society are due to excessive repression that I welcome any harmless channels for the deflection of urges which might otherwise manifest themselves in a manner harmful, or even merely disagreeable to society.’ He suggested that ‘Peeping Toms’ and exhibitionists ‘should be sentenced to regular attendance at a Nudist Camp’. Nudism’s distinctiveness came from looking at the bodies of others in a disinterested way. The founder of Spielplatz, one of Britain’s oldest nudist clubs, established as a business in 1930, argued that ‘it is just as pleasant to look upon well-kept human bodies as upon fine horses, race-hounds or birds on the wing’. In his club, he told aspiring members, ‘you will admire the beautiful, pity the others, and resolve to look to your own with an eye to its improvement.’

A Corner of the Restaurant from A Confidential Chat About Spielplatz, 1948 edition. Courtesy of the Spielplatz Estate Archive

This was all very well in the spaces of the club, populated by nudists of all ages and sizes. One attendee, the philosopher C E M Joad, described nudist camps in 1938 as ‘the chastest places I have ever visited. After one has been there 10 minutes,’ he observed, ‘the bodies of the other sex are no more attractive than carcasses in a butcher’s shop.’ But those who produced nudist magazines had other ideas about who should be looked at. Wrinkly, paunchy or hairy nudists going about their daily camp routines – frying breakfast or digging a latrine – were side-lined in favour of photographs of naked showgirls and buff body builders arranged alluringly in pastoral settings. These, their promoters argued, provided readers with ‘inspiration’. By contrast, ‘dull and unartistic photographs of camp life’ could put off the ‘hesitant novice’. The photographs acted as a ‘shop window’ for their ‘great movement’ which, they said, ‘can only flourish if it is continually expanding. We need to convert more and more people to our beliefs to help restore sanity and simplicity to the world.’

By the end of the 1930s, nudist membership was at an all-time high in Britain, with around 40,000 members. New nudist magazines were launched, boasting readerships of more than 100,000 per issue; evidently, more people liked to look on than to join in. In wartime, nudists found new justifications for their cause, when sun and air were reconceived as ‘unrationed benefits’, and public health was a national priority. The photographic nude also took on new meanings in a wider culture where pin-ups were achieving popularity as imports from the US.

The British social research organisation Mass Observation noted the prevalence of images of women adorning servicemen’s billets, and conducted ‘an experiment in taste’ in 1944, providing soldiers, sailors and airmen with a dozen reproductions of famous paintings, graphic illustrations and photographs of cinema stars. The selection included a photograph from the nudist press of a naked model arranged around a rock under a cloudy sky, taken by the photographer Horace Roye-Narbeth. Known professionally as Roye, his photograph easily took first place in the appraisal; it was the only image no-one disliked. Reviewers used terms such as ‘full of life’ and ‘clean and decent’. A 22-year-old army private stated that the winning nude should be titled ‘Worth Fighting For’.

Contemplation (c1944) by Roye. Courtesy of Vanessa Gibson of the Colin Narbeth Collection

Nudes were perceived as a national tonic under wartime conditions, and their viewing was restorative. But nudists were aware that there could be right and wrong ways of looking. A quiz in Sun Bathing Review in 1945 asked: ‘How Good a Sun Bather are You?’ To pass the test, readers were expected to be able to identify the Sun’s actinic and abiotic rays, the relative merits of artificial sunlamps, and a list of foods containing Vitamin D. ‘Good’ nudists were those who understood the practice intellectually. But highly educated members worried that readers were looking at depictions of flesh for less than scholarly aims. The experimental psychologist J C Flügel, for example, had warned a 1938 meeting of the Sex Education Society that ‘even the editors of our nudist magazines must admit that most of their readers are attracted by a sexual interest in the pictures’.

Nudist newsstand magazines offered an accessible, cheap and morally justifiable supply of nude photographs at a time when pornographic material was illegal and hard to find in the public domain. Contributors to forums in nudist publications, however, were at pains to maintain nudism’s non-sexual status. Members argued that ‘The true naturist regards his nudity as something unaffected and natural, simple and open. This, or a proper photographic representation of it, should have no provocative effect,’ they claimed, ‘except, perhaps, to a sex-mad mind, which will, in any case, find vice in the most innocent subject.’ Others countered that nude photographs were known to be sold for sexual stimulation, but stalwarts insisted: ‘There is nothing surreptitious about the display of genuine naturist illustrations’; these ‘do more to encourage a clean view of nudity than all the morality talks in the world.’ To the general population however, public nudity remained contentious. Some religious leaders were certain that nudism was depraved. Even among those with more moderate views, nudism was often a laughing matter, the butt of smutty jokes laden with innuendo and a popular subject for comic picture postcards.

Some nudist magazine photographers were working both above and below the counter

What we might consider the ‘clean view of nudity’ offered by nude photographs in mid-century Britain was visually particular. To stay on the right side of obscenity law, genitals and pubic hair had to be concealed. This meant that the subjects of nudist photographs often turned their back to the camera (buttocks were permissible), were cropped from the hips down (breasts were allowed) or offending areas were otherwise concealed by strategically placed limbs or props. When uninterrupted full-frontal or side views were included, genitals had to be clouded out in post-production by ‘retouching’ – scratching out the offending parts on the photographic negative. Nudists complained that their principles of freedom from shame and liberation from convention were compromised by these treatments. They reinforced the idea of forbidden fruits and warped the nudist message.

Beauty on the Beach by Roye from Health and Efficiency magazine, September 1946. Courtesy of Vanessa Gibson of the Colin Narbeth Collection

By the 1950s, nudists had established their health case and were achieving some mainstream acceptance. At the same time, they were resigned to the fact that, as one regular contributor observed in Sun Bathing Review in 1951: ‘Nudism and photography seem to go hand in hand, whether we all like it or not.’ He reflected: ‘It has been said that all nudists are photographers,’ but he regretted that ‘not all photographers are nudists.’ In a period when popular magazine publishing boomed – often featuring pin-up, glamour or ‘cheesecake’ photographs of women, and ‘beefcake’ photographs of men – and when censorship was reaching new heights, the government cracked down on salacious printed material. Nudist publications mostly escaped seizure and destruction. Some nudist magazine photographers, however, were working both above and below the counter, producing outdoor nudes for health publications but also titillating content for pornographic periodicals, often using the same models. Young women might splash in the foam or roll in the hay in nudist publications like Health and Efficiency, but they wore baby-doll negligees and fishnet stockings in glamour magazines like QT.

Roye was a photographer who inhabited both domains. His outdoor nudes had roused servicemen’s spirits in the 1940s, but a decade later he was experimenting with new methods, producing 3D publications of the ‘blonde bombshell’ British film star Diana Dors, nude but for diamonds and furs. The photographs’ immersive effects were achieved by wearing red and green 3D spectacles. In the late 1950s, Roye pushed boundaries further by publishing ‘unretouched’ photographs of nude models. The photographs were those previously supplied to the nudist press but, in his private subscription editions, models’ pubic hair was now visible. For this, he was charged in 1958 with the publication of an obscene libel.

Roye photographing Diana Dors in his studio, c1954. Courtesy of Vanessa Gibson of the Colin Narbeth Collection

To protect himself from prosecution, the arguments that Roye presented in court from his supporters were remarkably similar to those used by the early nudist press. The ‘natural’ unretouched state of the nude models, especially when depicted in outdoor settings, helped support the claim that Roye’s nude photographs were less ‘synthetic’ than those produced with artificial light and highly made-up models in studio settings. Such photographs – described as ‘semi-clad illustrations in contemporary magazines’ – were blamed ‘for the waves of juvenile delinquency, which are sweeping the world’. Another supporter stated, unequivocally: ‘the solution to the great social problems of sex education and our responsibility to women and children lies in the revision of our publishing laws, enabling the mind to reconcile itself to regard the human body as something natural, beautiful and, above all, wholesome.’ These arguments seemed to relate to the viewing of only young women’s flesh but, nonetheless, they were persuasive enough for Roye to be acquitted.

The 1960s are associated with permissiveness and sexual liberation. Given British nudists’ 40 years of campaigning, it might seem that their ideas would come of age in the decade. Magazines and feature films calling themselves ‘nudist’ certainly proliferated, but few had genuine links to the club cultures and non-sexual principles of nudism’s founders. Instead, they co-opted nudist terminology and arguments to promote their own agendas and to stay on the right side of the law. The campaigners for sexual liberation also called for public nudity as part of a wider relaxation of moral codes but the two groups rarely overlapped. Young hippies had no need for nudist club cultures, bound by rules and committees, and whose morals seemed dated. Nudists of the old school, in consequence, faced two opposing paths. They could either restate their opposition to sexual cultures more forcefully and enforce their own separatist identity – which many did by formally rebranding themselves as naturists and organising themselves into a national campaigning body; or they could embrace the changing times, and admit the sexual aspects of public nudity. Those who took this route saw themselves as truth-tellers and liberators as they smoothly manoeuvred their magazines towards soft pornography and their clubs into swingers’ bars.

By the end of the decade, the ‘pink wars’ had been won. The showing, first, of pubic hair, and then exposed genitals, ceased to be a prosecutable offence in Britain. Nudists, however, were pushed to one side. ‘We were the hardy pioneers,’ noted a contributor to Health and Efficiency in 1970, ‘who took all our clothes off long before the mere idea of a body in the buff could be projected with as much freedom and vigour as we find today at pop festivals, in papers and magazines, on screens and stages.’ This naturist complained: ‘But the permissives of 1970 are not even grateful!’

A hundred years after the first tentative attempts to establish nudism as a collective cause in Britain, some of the founders’ ambitions may seem wrongheaded, quaint or merely curious. But as I assembled my recent book on the subject, Nudism in a Cold Climate: The Visual Culture of Naturists in Mid-20th-Century Britain (2022), the echoes of their claims were still everywhere to be heard. A book about nude photography with a nude on the cover still cannot be sold on most bookselling platforms in the 21st century. Facebook and Instagram will not allow uncensored images from the book’s contents to be shown, even those with historic retouching or otherwise concealed pubic areas. Breasts and buttocks, deemed harmless a century ago, are now forbidden by social media moderators, our new censors. Nudists have long argued that seeing the bodies of others would open minds from repressive tradition and lead to a fairer world based on knowledge. The 50-year moral battles that were won for photography in print in the 1970s are still being fought on social media more than 50 years later.