Listen to this essay

23 minute listen

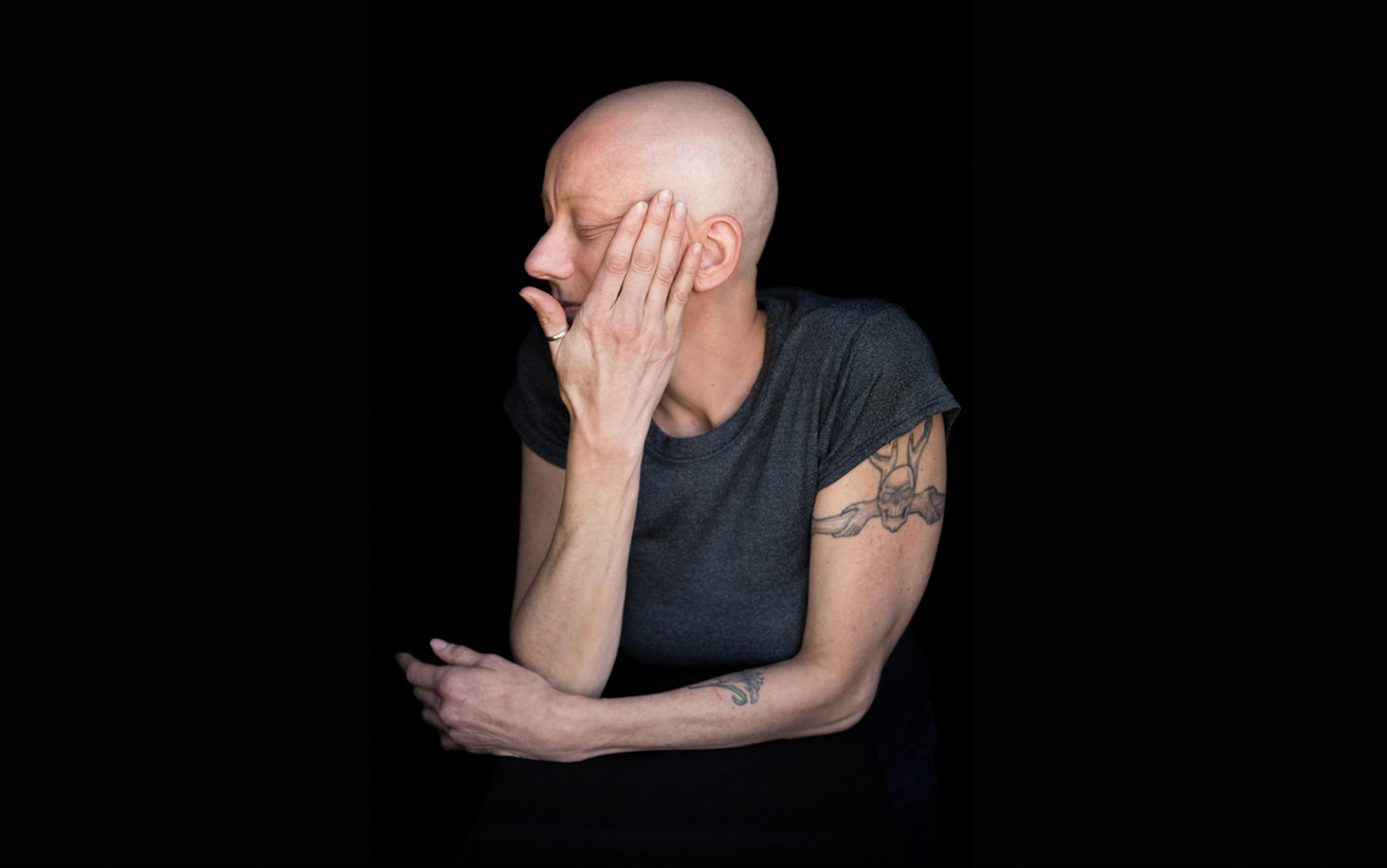

‘The initial weeks of this turmoil were pure hell. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, and I had burning in my mouth, throat, ears, and nose 24/7. I want to die just to stop the burning … feels like something is “tearing” into my stomach … I eat, I suffer. If I don’t eat, I suffer. I’m being bullied by my body.’

These words, written by a user of an online community dedicated to reflux diseases, capture something we rarely acknowledge: despite all the scientific and technological marvels surrounding us, pain and suffering can be just around the corner. What begins as ‘mere heartburn’ escalates, for some, into an odyssey of suffering that seems to resist every intervention our information-rich world can offer.

This is the paradox of chronic illness today. Never before have humans possessed such convenient access to abundant medical knowledge, expert guidance, health influencers, and communities of fellow sufferers. Expertise flows across digital networks, promising hope for every ailment. Yet, paradoxically, this abundance can become a source of suffering. Instead of finding relief, many individuals suffering from chronic illness find themselves descending into a spiral of suffering – a cruel journey where each piece of information, whether from expert opinion or laypersons, may offer hope momentarily, but over time deepens their distress.

While diseases such as cancer, AIDS, ALS, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis and diabetes often evoke deep fear, sympathy and collective urgency – reflected in dedicated charities, advocacy groups and public awareness campaigns – there exists an under-recognised class of bodily conditions that also wreaks havoc on human lives. These illnesses often receive little social legitimacy and may even be dismissed by medical professionals, family members and society at large as mere tiredness, laziness or psychological fragility. Conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Long COVID and Lyme disease are often dismissed as trivial, yet they can be profoundly disabling. Though not usually life-threatening, these overlooked illnesses can dismantle a person’s social, professional and emotional world, leaving sufferers severely disadvantaged – often without the sympathy or structural support afforded to more widely recognised diseases.

Reflux diseases are among the many conditions that can trap sufferers in a spiral of chronic suffering. The category includes both gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). In GERD, stomach acid, digestive enzymes and other gastric contents rise into the oesophagus, whereas in LPR they reach even higher into the throat, airways and voice box. GERD often produces burning in the chest and oesophagus, while LPR tends to cause throat burning, hoarseness, chronic cough, postnasal-drip sensations and even nerve pain – frequently without any heartburn at all. In severe cases, long-term irritation can contribute to oesophageal or throat cancer.

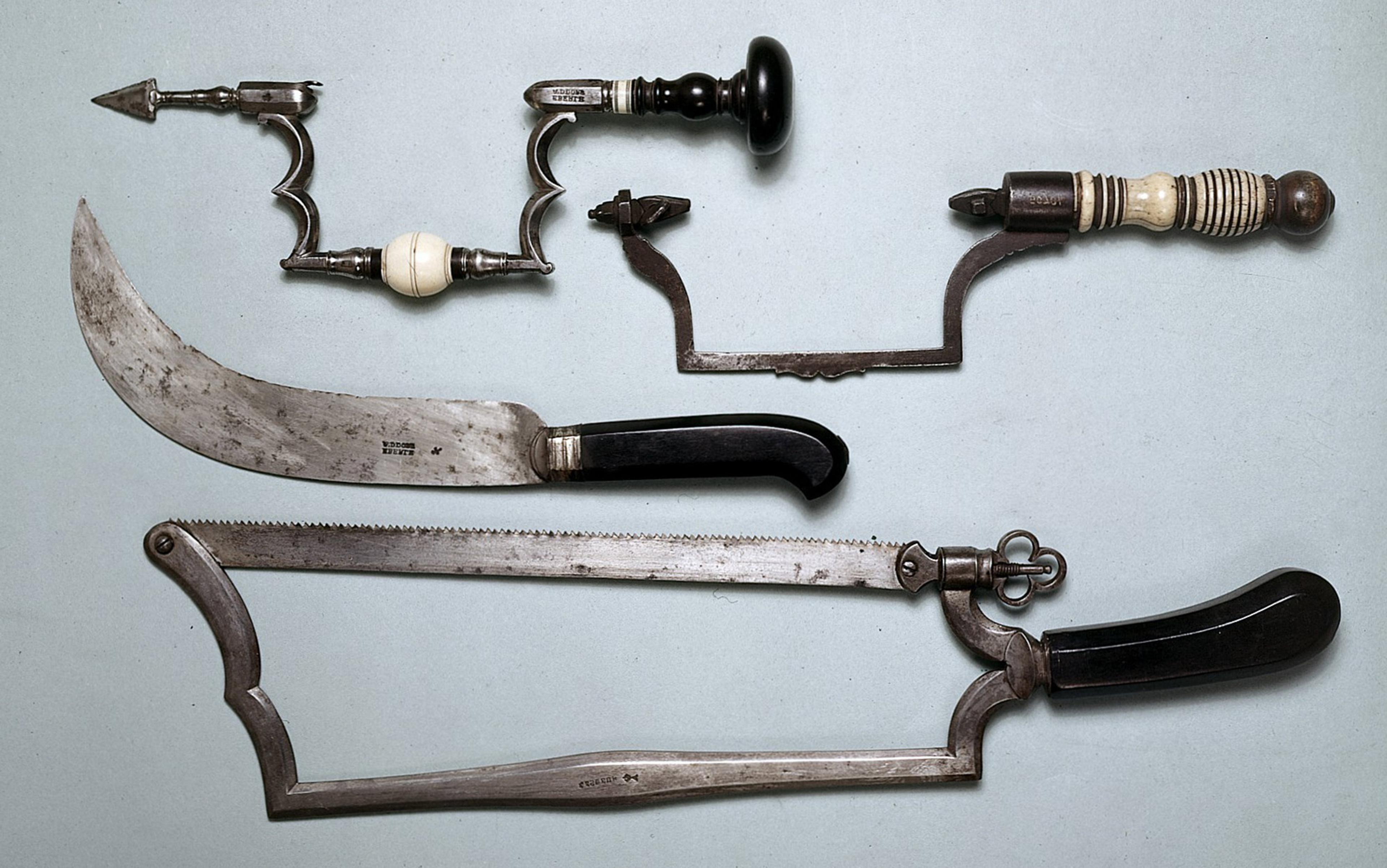

These brutal conditions are neither mysterious like Long COVID, whose causes and progression remain uncertain, nor urgent like cancer. Instead, they occupy an uncomfortable middle ground: familiar, longstanding and supposedly manageable. Recognised for thousands of years, reflux diseases were formally described by modern medicine in the 18th century, and have recently become especially widespread and disruptive. Some estimates suggest that reflux diseases affect between 10 and 20 per cent of various populations worldwide, with lower but increasing numbers in East Asia.

These treatment-resistant cases expose systemic gaps in how medical professionals address chronic illness

Like some other chronic conditions, reflux may be seen as minor yet it can quietly dismantle lives. Here is a condition that affects hundreds of millions, has well-established treatments, and seems manageable from the outside. Yet our study of online communities dedicated to this disease reveals numerous voices documenting years of failed medical interventions, contradictory and unbounded layperson advice, and gradual erosion of hope and trust in expertise itself. Sufferers can be left with a depressing realisation that modern medicine and the deluge of layperson advice cannot reliably heal something as seemingly straightforward as gastric fluids rising into places they do not belong.

As researchers studying expertise and organisational responses to chronic illness, we bring both scholarly training and lived experience to this investigation. Siddhant, in particular, studies suffering as a symptom of the limits of both professional and lay expertise. This dual perspective led us to conduct a systematic analysis of online communities where chronic illness sufferers worldwide gather to voice and document their journeys of pain, dismissal and desperation, as well as hope, empathy and camaraderie. In examining these digital archives of struggle, we discovered how seemingly ‘manageable’ conditions can become sources of profound, intractable suffering, not just despite but often because of our information-rich environment.

The research focuses on a specific subset of reflux patients: people whose symptoms persist despite standard treatment and who turn to online communities for support. While estimates vary, studies suggest that 10-40 per cent of GERD patients experience inadequate symptom control with conventional therapies. Only a fraction of them join online forums, and those who find relief often leave, creating a kind of survivorship bias – except here, the ‘survivors’ are the ones still suffering. This makes the sample especially valuable for understanding the spiral of suffering for those who stay online. These treatment-resistant cases expose systemic gaps in how medical professionals address chronic illness. Their prolonged suffering merits attention because they are the patients most likely to be dismissed and disappear from public discourse, and the ones most endangered by misinformation and even abuse online.

Reflux disease inhabits the desert of medical dismissals. It does not always arise with urgency but rather through the slow erosion of what most people would consider ‘normal’ life. This erosion includes the surrender of favourite foods, social dinners, spontaneous plans, and restful sleep. The suffering of reflux disease is almost inescapable: people must eat and drink, and that itself rouses the demon. To complicate matters, even if someone is regimented in their diet and lifestyle, there is always a slip-up or unknown ‘trigger’ lurking. It can seem like there is no escape. Of course, the sufferers are desperate to find relief, and seek the expertise of the professionals – physicians.

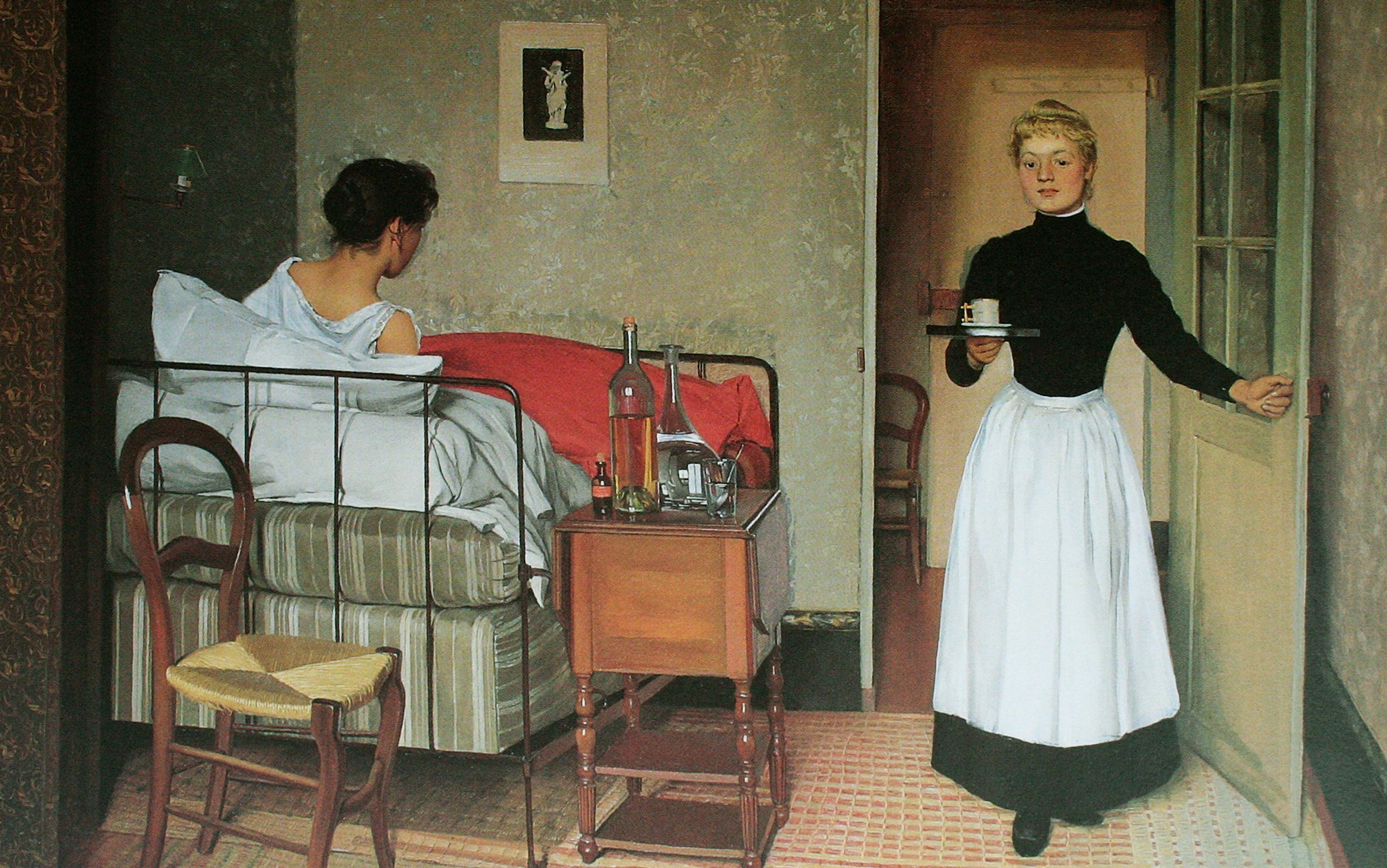

Alas, the online communities we studied were quite full of stories from sufferers feeling let down or belittled by their physicians. In this, reflux joins a cruel fraternity of suspect conditions from endometriosis (dismissed as ‘normal’ monthly pain) and chronic fatigue syndrome (invalidated as psychological weakness) to Long COVID (debunked as a figment of imagination, said not to exist at all).

‘The doctors are so infuriating,’ writes one reflux sufferer. ‘My gastroenterologist didn’t even think that my burning mouth is a problem. It is my biggest complaint. I explained to him every time I saw him … Asshole didn’t think that the thing driving me crazy was important enough to add to my notes.’

In our democratised era, anyone with internet access can become both a teacher and a healer

There are countless ways in which physicians belittle, gaslight, and deny the legitimacy of suffering. And if physicians do not recognise the suffering then, for all intents and purposes, the problem does not exist. Here lies the first betrayal that contributes to the spiral: those trained to witness, acknowledge, and treat suffering sometimes turn away from it and, worse, deny its existence. For reflux patients, this dismissal is particularly cruel because their condition is assumed to be manageable. Patients’ mounting anxiety turns into an existential crisis. To be dismissed when your pain has never been so all-consuming and unrelenting by the very profession entrusted to heal you is to experience the shock of abandonment and the collapse of one’s own reality. This misrecognition by physicians and society acts as a double burden: not only must sufferers endure relentless pain from the refluxate creeping into their throats and oesophagus, but they must also navigate a medical world and a society that question whether their experience warrants serious consideration at all.

No wonder sufferers are envious of people with severe but treatable illness, as this quote illustrates:

We can fly people to the moon but can’t fix such a seemingly simple thing [reflux] that causes so many issues. At this point I envy my friend who was born with diabetes where she needs insulin. Theoretically that’s a far more severe disease. But so what, she’s living perfectly fine and has no issues other than ‘Oh, it’s time to take insulin.’

When professional medicine fails them, sufferers routinely seek refuge and support from the fellow-sufferer. In a digital society, anyone with internet access can become a sufferer, a teacher and a healer, all at once. For those tired of rejections from medical professionals, online communities dedicated to their specific suffering become oases in an otherwise forbidding desert.

At the outset, many new members find a community full of empathy, understanding and shared experience. This initial relief is a revelation for many users. After months of being told their symptoms exist ‘in their head’ or spring from ‘stress’, sufferers finally encounter souls who believe them. ‘As I said, I’m not a doctor,’ writes one digital companion. ‘But as a human, I can understand the human side of this suffering.’ Another responds: ‘Wow, I felt every word you said.’

This validation feels like resurrection of self, the first recognition that their pain is real, their struggle legitimate, their experience worthy of witness and care. But while initially healing, validation from fellow sufferers can be a trap. Sufferers, of course, cannot stop at validation and understanding; they crave deliverance. And online lay communities eagerly attempt to offer it.

When life is riddled with suffering, there’s never any shortage of those selling salvation for a buck

Here’s the irony: the same accessibility that makes these sanctuaries possible also makes them treacherous. Unlike physicians bound by a professional code of ethics, diagnostic and treatment protocols, legal and social norms, layperson advisors, anonymous or otherwise, largely operate in a realm beyond accountability. Their prescriptions can range from merely futile to genuinely dangerous – exotic supplements, experimental diets, exercise regimens and surgical procedures performed in distant countries by practitioners operating outside conventional oversight. Of course, such advice sometimes comes with responsibility-eschewing caveats, such as: ‘I am not a doctor, but…,’ or ‘This worked for me, but everyone is different, YMMV [your mileage may vary],’ perhaps to pay lip service to loosely enforced moderation rules regarding treatment and diagnostic advice.

Naturally, sufferers are frustrated with lay advice and its capricious promise. ‘I’d be OK with following the standard advice if there was some fucking consistency!’ cries one exhausted voice from the digital wilderness, about the capriciousness of layperson advice. ‘Oh, don’t eat acidic foods – Oh no, actually, you need to acidify your stomach to digest your food … Take this PPI [proton pump inhibitor] to treat the symptom (oh BTW it won’t actually heal your LES [lower oesophageal sphincter] so good luck dealing with that without surgery).’ After some time, when the surge of feel-good hope and recognition wears off, the absurdity hits home:

No one talks to a diabetic and says ‘don’t follow Doctor’s advice! You need to eat a lot of sugars to supersaturate your body and improve insulin production thereby making your body more insulin sensitive! It worked for me and my aunt – don’t give your money to big pharma!’ No one with a functioning brain would advise that.

The contradictions in lay advice just expand the locus of suffering. If the body’s pain is a direct assault, the anguish gets compounded by the false expectations and betrayals of fellow sufferers (if all the anonymous others online even are fellow sufferers, as they claim). After all, when there is suffering, there’s never any shortage of those selling salvation for a buck. When that promise and the accompanying hope crumble, when cutting-edge medicine cannot heal a ‘simple’ issue of reflux, and the internet’s infinite wisdom offers only confusion, the disappointment becomes its own source of torment.

The resulting downward spiral is rarely gentle and eventually reaches a kind of terminus. One endpoint, the state of resignation, is captured by this quote:

It has been a year since this began. I’ve tried PPIs, all sorts of blood tests, ultrasound, antibiotics, rifaximin, dietary changes, probiotics, and sleeping sitting upright. I even spent 2 months in the hospital with a feeding tube in my stomach … every day I’m suffering from burning in my throat … I want to live so much, but I really feel I can’t do this anymore.

The highly publicised case of Luigi Mangione brings potential consequences of resignation to light. His story reveals something we would rather not acknowledge: that when human beings are pushed beyond their capacity to suffer, the spiral can end in violence. Before his arrest for the assassination of the UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December 2024, Mangione had spent years descending through the rabbit hole of online forums for chronic back pain, documenting his transformation from hopeful patient to aggrieved exile. His digital footprints reveal the familiar story: chronic pain after a pivotal moment, initial faith in medical professionals, mounting frustration with failed interventions, desperate experimentation, many years of invisible suffering and, finally, the bitter recognition that the system designed to heal him had instead abandoned him. While his alleged actions remain inexcusable, they illuminate something we cannot ignore: the violent terminus of an untreated spiral of suffering.

Another endpoint is the grim acceptance of adaptation. Here sufferers construct a severely constrained life around symptoms that refuse to yield. ‘Life was so good just eight months ago. I could do and eat anything. Now I’m on house arrest. I can’t socialise. I can’t eat,’ writes one such prisoner. ‘I was a healthy social guy, now I am a social pariah.’ These individuals build elaborate fortresses of behaviour around their symptoms, trading spontaneity and social connection for a treacherous and elusive sense of control.

Some sufferers learn to navigate the wilderness of online advice with sophisticated discernment

A third cruel outcome is mistaking temporary relief for a permanent cure. One sufferer recalls how this goes:

I started taking TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants) like Amitriptyline. They are antidepressants, but they are often used for nerve pain. It was like night and day. My symptoms receded more and more, and I couldn’t believe it. Honestly, typing this sounds like some sort of infomercial for a miracle cure. I can’t stress enough how relieved I was, after two years of absolute hell.

Unfortunately, ‘cures’ are often temporary or mistaken. For example, the same person later wrote that the treatment became unusable:

Amitriptyline worked, but due to side effects I switched over to Nortriptyline … Nortriptyline did an excellent job of masking my symptoms, but after trying some trigger foods, I realised I wasn’t healed.

A fourth pathway through the spiral, and the reason why hope springs eternal, is of course breaking through. Some sufferers learn to navigate the wilderness of online advice with sophisticated discernment, treating online communities as waypoints rather than final destinations. And sometimes they do find treatments that reduce or eliminate their suffering, even long term. The online forums we studied contained these rarer but crucial narratives of success. One user shared their decade-long journey: ‘I’ve had gut issues since high school. Standard doctors basically assumed it was genetic GERD (since I wasn’t overweight or older) and told me to take PPIs for life, which I did for about 10 years.’ Rather than accepting this life sentence, they wrote about seeking functional medicine: ‘After running SIBO [small intestinal bacterial overgrowth] and stool tests, we found bacterial overgrowth. I went through an antimicrobial protocol and now I’m rebuilding with probiotics.’ The breakthrough came with a specific intervention: ‘The breakthrough came when I started prucalopride, a pro-motility drug. Before that, I woke up every night around 3 am to pee, had frequent nighttime reflux, and was chronically constipated. Since the first day of starting it, I sleep through the night and no longer deal with constipation.’

What distinguished this account was their mechanistic insight:

The likely mechanism: slow gut motility plus bacterial overgrowth means food ferments too long in the small intestine. That leads to excess gas, pressure, and histamine release, which can irritate airways, trigger post-nasal drip, and cause nighttime awakenings. By improving motility, food clears before it ferments, reducing reflux, bloating, and sleep disruptions.

Not all breakthrough stories in the forums came with such clear explanations. Another user documented their systematic approach: ‘I got off year-long Omeprazole 40 mg use about 45 days ago. I had to be on alginates for 1 month to prevent rebound reflux. Meanwhile, I started to aggressively rebalance my gut microbiome.’ They detailed their methodical protocol – prebiotics, probiotics, specific foods – before reporting: ‘It’s been 15 days without any antacids and I don’t have reflux anymore. My energy levels are much higher and mental clarity is back.’ Yet their honest confession captured the mystery that can accompany even successful navigation: ‘I have no damn clue how this even worked.’ Crucially, they demonstrated the ethical responsibility often absent in desperate advice-giving, conceding: ‘Of course this ain’t medical advice, the journey has been a bit brutal as I experimented on myself, but it was worth it… everybody is different. What didn’t work for me might work for you.’

Commonly, sufferers move among these states, drifting back and forth as though navigating a maze – and this frustrating experience is hardly unique to gastrointestinal illness. Similar patterns surface in addiction, grieving, and chronic pain. The drive to find clear answers where none exist can push us toward explanations that merely appear definitive, or lead some – physicians included – to experiment with treatments that are risky, unproven or unlikely to work. The fact remains that, for certain conditions and certain sufferers, the mystery of suffering persists despite expertise, discipline or exhaustive effort. So how do we confront the spiral of suffering?

First, we can begin by recognising that, while we may not be able to solve every problem, we should not abandon the sufferers. For physicians, even saying: ‘I don’t know what’s causing your pain, but I believe you, and I’m here’ can be powerful. Good medicine includes managing expectations and tending to the pain of illness and the pain of dashed hope. A trusting relationship will make it more likely that sufferers will run their ‘alternative medicine’ trials by their physicians, thereby preventing grievous injuries to health. Ultimately, if there is no cure, then presence is the most profound form of care.

Second, since digital spaces can feel like sanctuaries and yet just as easily become sites of harm and false certainty, it’s crucial that online health communities and influencers act with greater responsibility. Their value lies less in offering solutions than in offering witness. A simple ‘I understand your suffering’ is often safer and more meaningful than an unsolicited regimen or risky treatment suggestion. We need digital spaces capable of holding both validation and restraint, where ‘I don’t know’ becomes an act of care rather than an admission of defeat.

Their struggle is universally human. We all live in bodies that will one day fail us, searching for answers that may never come

Third, we need better public education in evaluating health information and managing suffering. Particularly, when suffering isn’t scientifically validated, it is often treated as unreal, creating a vacuum where confusion and quackery flourish. Media literacy helps, but is not enough in moments of vulnerability. What we most need is a kind of ‘suffering literacy’: an understanding that illness, uncertainty and limits are part of life, and that science and technology cannot always eliminate them. Such literacy requires a cultural reckoning with the delusion that progress will conquer all problems. Indeed, the spiral of suffering often begins when the promise of technology collides with the limits of the human condition. So, while some pain remains intractable, literacy in the contours of suffering may prove to be a prophylactic.

The person who wrote they were ‘bullied’ by their body deserves more than pity or false promises; they deserve recognition. Their struggle is deeply personal yet universally human. We all live in bodies that will one day fail us, searching for answers that may never come.

The spiral of suffering thrives in isolation, in the gap between what we expect and what we receive, but it softens in the presence of genuine witnesses. Many around us inhabit oceans of suffering and sometimes the best available medicine is not a cure but companionship – a willingness to sit with others in the mystery and intractability of their pain.